The Predictive Role of CD40L in The Development of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in A Murine Model: A Pilot Study

Article Information

Nikolaos Patelis1,2, Dimitrios Moris3, Spyridon Davakis2, Chris Bakoyiannis2, Theodore Liakakos2, Sotirios Georgopoulos2

1Athens Medical Center, Marousi, Athens, Greece

2First Department of Surgery, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Laiko General Hospital, Athens, Greece

3Department of Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA

*Corresponding author: Nikolaos Patelis, Athens Medical Center, Marousi, Athens, Greece

Received: 24 May 2019; Accepted: 04 June 2019; Published: 07 June 2019

Citation: Nikolaos Patelis, Dimitrios Moris, Spyridon Davakis, Chris Bakoyiannis, Theodore Liakakos, Sotirios Georgopoulos. The Predictive Role of CD40L in The Development of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms in A Murine Model: A Pilot Study. Cardiology and Cardiovascular Medicine 3 (2019): 108-117.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

The mechanism behind the incidence and the development of infrarenal aortic aneurysm and the factors affecting the rate of aortic dilatation remain largely unknown. The need for a biomarker capable to facilitate the diagnosis and the timed repair of an aortic aneurysm could reduce overall mortality. The aim of this study is to report on the potential predictive role of CD40L in aortic diameter growth and the development of AAA. The study group of 16 Wistar rats underwent a laparotomy and an infusion of porcine pancreatic elastase of the infrarenal aorta under hydrostatic pressure. The control group (n=16) underwent a sham procedure. At an interval of seven days, the animals of both groups underwent a laparotomy and the aortic dimension was measured. Blood samples were obtained at the same intervals. No significant change of the animals’ weight was recorded. AAA was formed in all animals and aortic diameters differed significantly between the two groups. After the intervention, CD40L demonstrated a gradual increase in the study group and CD40L serum levels in this group were significantly higher compared to the control group; in parallel with the trend of aortic dilatation. CD40L could potentially act as biomarkers of the presence and development of infrarenal aortic aneurysms, but further studies with a larger number of animals are necessary.

Keywords

Aneurysm; Biomarker; Rupture; Animal Model; Abdominal Aorta

Article Details

1. Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a lethal disease affecting a significant percentage of males over the age of 65, while it is rather infrequent in females [1-3]. Aortic dilatation and aortic aneurysm are defined as aortic diameter growths by less or more than 50% compared to normal aortic dimensions, respectively. AAA can lead to aortic rupture, a life-threatening event that even if it is urgently addressed it still carries significant post-procedural morbidity and mortality [4]. At present, AAA rupture is becoming less frequent as surveillance programs and non-invasive medical imaging (e.g. coaxial tomography – CT, ultrasound scan - US) assist in the early diagnosis and elective treatment of AAA or aortic dilatation [5-8]. AAA repair is considered only if the AAA is large (≥55 mm), symptomatic or rapidly growing (≥10 mm per year) [9]. Based on the current guidelines, small asymptomatic aneurysms or aortic dilatations are not subjected to annual follow-up imaging or elective repair, leaving these cases follow the natural course of the aneurysmal disease until they are either symptomatic or large enough to be electively repaired [10,11]. As a result, there is no cost effective and easy method to screen aortic dilatations until their dimensions grow significantly. Blood biomarkers could potentially fill in this role and provide the necessary prediction of significant aortic growth. The term biomarker is defined by World Health Organization as any substance, structure, or process that can be measured in the body or its products and influence or predict the incidence of outcome or disease [12]. To date, no definitive biomarker for AAA growth has been described, despite the rather big number of related studies [13-15]. CD40L is the ligand of the CD40 transmembrane protein and plays a significant role in the stimulation and regulation of the cellular immune response, through T-cell priming and activation of CD40-expressing immune cells. It has a significant role in both the inflammation and the atherosclerotic processes.

The aim of this study is to report on the potential predictive role of CD40L in aortic diameter growth and the development of AAA.

2. Materials & Methods

This protocol was approved by the General Directorate of Veterinary Services, National Bioethics Commission, according to Greek legislation regarding ethical experimental procedure, in compliance with the EEC Directive 86/609 and Act 2015/1992 and in conformance with the European Convention ‘for the protection of vertebrate animals used for experimental or other scientific purposes”. This study was performed at the Laboratory for Experimental Surgery and Surgical Research “N.S. Christeas” (European Ref. # EL 25 BIO 005). Animal handling and care was in accordance with the National guidelines for Ethical Animal Research and the Principles of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction and Refinement) [11]. All efforts were made to minimize suffering. Animals were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment with ad libitum access to water and food. Lighting conditions mimicked the daily variation of light in nature.

The murine model used in this study is a variant of the experimental in vivo model of aortic aneurysm development with PPE infusion, which was first developed by Anidjar et al. [16]. Our research team has previously published the used variation of the original experimental protocol [17].

Thirty-two wild-type male Wistar rats were recruited, weighted and then equally distributed in two groups: AAA and control (n=16 in each group). In the AAA group, animals were subjected to laparotomy under general anesthesia and their aortas were perfused for 5-15 minutes with a solution of 4.5 U/mL Type I porcine pancreatic elastase (PPE). The perfusion was performed under hydrostatic pressure of 100 mmHg. The aim of the perfusion was to dilate the aorta by maximum 50% of its original diameter and it was defined as T0. In a similar manner, the aortas of the control group were perfused with natural saline 0.9% solution without the effect of hydrostatic pressure. Each animal underwent two additional laparotomies on day 7 (T7) and day 14 (T14). The aim of these laparotomies was measuring the aortic diameter.

Blood sample collection was carried out through orbital sinus at T0, T7 and T14. CD40L serum levels were quantified using the ELISA technique (CD40L ELISA Kit, BluGene, China), and CD40L concentrations are reported as optical density (OD) values. We evaluated the correlation between CD40L and the development and progression of an AAA.

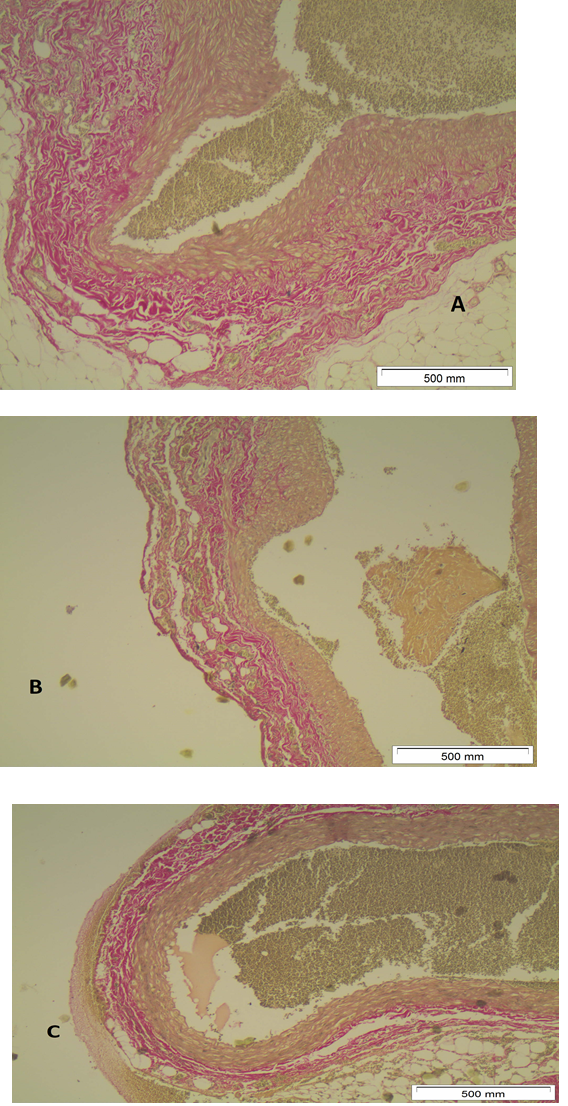

2.1 Histological examination

Histological studies were performed to analyze changes in matrix proteins. Van Gieson (VG) that stains collagen in red, nuclei in blue, and erythrocytes and cytoplasm in yellow was used. Aortic segments were removed and preserved in 10% paraformaldehyde before processing for embedding in paraffin blocks for classic histological examination.

2.2 Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. The normality of the distributions was assessed with Kolmogorov-Smirnov’s test and graphical methods. Between-group comparisons were performed using student’s T-Test and Mann-Whitney U test, where appropriate. Comparisons between multiple time points were performed using Repeated Measures ANOVA and Friedman’s test with Wilcoxon’s Signed Ranks test for post-hoc comparisons. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Spearma’s rho were calculated in order to examine relationships between variables. Differences were considered significant if the null hypothesis could be rejected with >95% confidence (two-sided p<0.05).

3. Results

The mean animal weight was similar between the AAA and control groups at all time points: 437±55.1gr and 429±65.9gr, 457±55.3gr and 415±62.5gr, 468±50.4gr and 416±67.4gr at T0, T7 and T14, respectively (p>0.05 at all points). No significant change of the animal weight was demonstrated within each group at different time points (Table 1).

|

Time |

Study group |

Control group |

p |

||

|

Mean weight |

SD |

Mean weight |

SD |

||

|

Τ0 |

437 |

55.1 |

429 |

65.9 |

NS |

|

Τ7 |

457 |

55.3 |

415 |

62.5 |

NS |

|

Τ14 |

468 |

50.4 |

416 |

67.4 |

NS |

Table 1: Animals’ weights at different time points for the study and the control groups

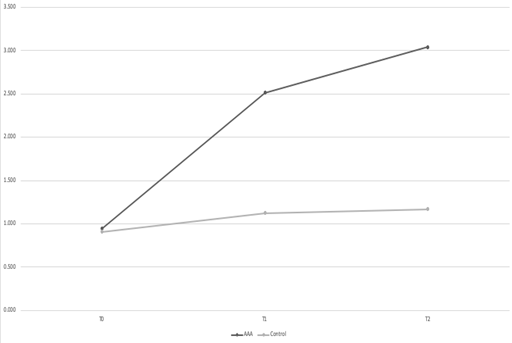

At T0, the diameter of the infrarenal aorta was similar between the two groups: 0.943±0.098mm and 0.909±0.082mm for the AAA and the control groups, respectively (p>0.05) (Figure 1). At T7, there was no significant difference between the two groups: 2.512±0.414mm and 1.125±0.112mm for the AAA and the control groups, respectively (p>0.05). At T14, the mean aortic diameter of the AAA group was significantly higher compared to the control group: 3.043±0.453 versus 1.168±0.115mm, respectively (p<0.05). The aortic dilatation of the AAA group at T7 was significant compared to T14, and at T14 was significant compared to both T7 and T0 (p<0.05 for all). Aortic diameters of the control group did not grow significantly in any time point (p>0.05 for all).

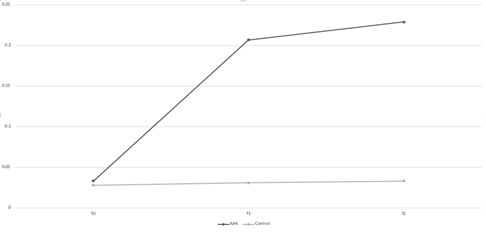

The initial concentration of CD40L was similar for the two groups at T0: 0.033±0.011 and 0.028±0.004, respectively (p>0.05) (Figure 2). At T7, CD30L concentration was significantly higher in the AAA group compared to the control group: 0.207±0.041 vs 0.031±0.003, respectively (p<0.05). At T14, the AAA CD40L levels were once more significantly higher compared to the control group: 0.229±0.046 vs 0.033±0.004 (p<0.05). CD40L concentration in the AAA group rose significantly rose from T0 to T7 (p<0.05), but it plateaued between T7 and T14 (p>0.05). The concentration of the control group did not rise significantly at any time point (p>0.05 for all).

At T0, sample staining with EVG, revealed no pathology or structural change of the aortic wall (Figure 3A). A gradual destruction of elastic fibers in the aortic walls starts at T7 and becomes more evident at T14 (Figures 3B,3C).

4. Discussion

CD40L (also known as CD154) is the ligand of the CD40 transmembrane protein. CD40L plays a significant role in the stimulation and regulation of the cellular immune response, through T-cell priming and activation of CD40-expressing immune cells. CD40L is also a type II transmembrane protein with a molecular mass of 32 to 39 kDa [18]. The soluble form of CD40L preserves the properties of the transmembrane form [19,20]. CD40L is a member of the Tumor Necrotizing Factor superfamily of molecules and it consists of one α-helix loop in between two β-sheets, arranged in a “sandwich” fashion [21,22]. This structure allows CD40L to trimerize; a common property for all TNF ligand molecules. CD40L is mainly expressed on the surface of stimulated T and B lymphocytes, and platelets [23-25]. In the process of inflammation, CD40L is also expressed on mononuclear cells, natural killer cells, mastocytes and basophilic granulocytes [25]. This wide expression of CD40L demonstrates its important role in the cellular immune response. The interaction of CD40 and CD40L leads dendritic cells to mature, produce cytokines, and activate T lymphocytes. It also stimulates the antigen cross presentation by dendritic cells and it promotes antigen-antibody affinity [26,27]. It is well recorded that the CD40/CD40L signal pathway is important for the survival of cells in the presence of inflammation; a role that is affected in autoimmune diseases [27, 28]. CD40L is also involved in immunoglobulin class switching. The expression of TNF Receptor Associated Factors (TRAF) 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 on the epithelial cells, macrophages and smooth muscle cells is regulated by proinflammatory cytokines, and amongst them by CD40L [29]. These molecules are important for both the normal structure of the blood vessels, but they are also important for the process of inflammation and atherosclerosis. Therefore, TRAF and CD40L signal pathway play an important role in these processes in blood vessels [30-33]. Apart from atherosclerosis, CD40L is also linked to atherosclerotic plaque complications and other atherosclerosis-related pathology, such as aneurysms [34]. It is also reported that the lack of CD40L and the consequent non-activation of CD40 protects individuals from the development of an aneurysm and its deadly complication – aortic rupture [35].

The selected animal model was technically successful, as it produced an infrarenal aneurysm in all the animals of the AAA group. This high rate of aneurysm induction as a result of PPE perfusion is already described in the literature and our results are in line with the published data [36]. At T14, the aortic diameter was significantly higher in the study group compared to the control group. In this group, a steep increase of the aortic diameter during the first seven postoperative days was observed. This increase was in parallel with an increase of the concentration of CD40L in a similar manner. CD40L concentration was significantly higher in the study group compared to the control group at both T7 and T14. The increase of the CD40L concentration between T7 and was statistically significant and it was followed in a similar manner by the aortic dilatation. At the bottom line, the two curves (CD40L concentration and aortic diameter) have a similar course. The fact that CD40L reaches statistical significance at T7 when aortic diameter reached statistical significance at T14 could mean that high CD40L levels may foretell further aortic dilatation. Of course, this is something to be explored further.

From these results, one could assume that CD40L is an analogue to the aortic dilatation and its higher concentration can predict a future aortic dilatation. This can be explained by the key role of CD40L in the mechanism of inflammation and T-cell mediated immune response, and the fact that inflammation of the aortic wall is the base on which the aneurysmal disease lies.

The present study has two weak points. First, the number of animals in each group is relatively small. Therefore, a larger study should follow in order to support our findings. Another weak point is that once a larger study on animals is completed and its evidence supports our findings, a similar study on humans should be undertaken in order to test whether these findings translate to human physiology. These additional studies should also focus on the threshold at which CD40L acquires a predictive role for AAA expansion.

References

- Gillum RF. Epidemiology of aortic aneurysm in the United States. J Clin Epidemiol 48 (1995): 1289-1298.

- Golledge J, Tsao PS, Dalman RL, Norman PE. Circulating markers of abdominal aortic aneurysm presence and progression. Circulation 118 (2008): 2382-2392.

- Blanchard JF. Epidemiology of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Epidemiol Rev 21 (1999): 207-221.

- Nedeau, April E., et al. Endovascular vs open repair for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Journal of vascular surgery 56 (2012): 15-20.

- Ashton HA, Buxton MJ, Day NE, et al. The Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) into the effect of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening on mortality in men: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 360 (2002): 1531-1539.

- Ashton HA, Gao L, Kim LG, Druce PS, Thompson SG, Scott RA. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial of ultrasonographic screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg 94 (2007): 696-701.

- Norman PE, Jamrozik K, Lawrence-Brown MM, et al. Population based randomised controlled trial on impact of screening on mortality from abdominal aortic aneurysm. BMJ 329 (2004): 1259.

- Zarrouk M, Lundqvist A, Holst J, Troeng T, Gottsater A. Cost-effectiveness of Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm in Combination with Medical Intervention in Patients with Small Aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 51 (2016): 766-773.

- Mortality results for randomised controlled trial of early elective surgery or ultrasonographic surveillance for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. The UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Lancet 352 (1998): 1649-1655.

- Devaraj S, Dodds SR. Ultrasound surveillance of ectatic abdominal aortas. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 90 (2008): 477-482.

- Flecknell P. Replacement, reduction and refinement. ALTEX 19 (2002): 73-78.

- Organization WH. International Programme on Chemical Safety Biomarkers in Risk Assessment: Validity and Validation. http://www.inchem.org/documents/ehc/ehc/ehc222.htm. Published 2001. Accessed 23/12/2018.

- Moris D, Mantonakis E, Avgerinos E, et al. Novel biomarkers of abdominal aortic aneurysm disease: identifying gaps and dispelling misperceptions. Biomed Res Int 2014:925840.

- Tsilimigras, Diamantis I., et al. Cytokines as biomarkers of inflammatory response after open versus endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a systematic review. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2018).

- Moris DN, Georgopoulos SE. Circulating biomarkers for abdominal aortic aneurysm: what did we learn in the last decade? Int Angiol 32 (2013): 266-280.

- Anidjar S, Salzmann JL, Gentric D, Lagneau P, Camilleri JP, Michel JB. Elastase-induced experimental aneurysms in rats. Circulation 82 (1990): 973-981.

- Moris D, Bakoyiannis C, Dousi E, et al. Novel protocol for creation and study of abdominal aortic aneurysm with porcine pancreatic elastase infusion in rats. Arch Hellen Med 32 (2015): 636-644.

- van Kooten C, Banchereau J. CD40-CD40 ligand. J Leukoc Biol 67 (2000): 2-17.

- Graf D, Muller S, Korthauer U, van Kooten C, Weise C, Kroczek RA. A soluble form of TRAP (CD40 ligand) is rapidly released after T cell activation. Eur J Immunol 25 (1995): 1749-1754.

- Mazzei GJ, Edgerton MD, Losberger C, et al. Recombinant soluble trimeric CD40 ligand is biologically active. J Biol Chem 270 (1995): 7025-7028.

- Karpusas M, Hsu YM, Wang JH, et al. 2 A crystal structure of an extracellular fragment of human CD40 ligand. Structure 3 (1995): 1426.

- Karpusas M, Lucci J, Ferrant J, et al. Structure of CD40 ligand in complex with the Fab fragment of a neutralizing humanized antibody. Structure 9 (2001): 321-329.

- Carbone E, Ruggiero G, Terrazzano G, et al. A new mechanism of NK cell cytotoxicity activation: the CD40-CD40 ligand interaction. J Exp Med 185 (1997): 2053-2060.

- Grewal IS, Flavell RA. CD40 and CD154 in cell-mediated immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 16 (1998): 111-135.

- Miga A, Masters S, Gonzalez M, Noelle RJ. The role of CD40-CD154 interactions in the regulation of cell mediated immunity. Immunol Invest 29 (2000): 111-114.

- Danese S, Sans M, Fiocchi C. The CD40/CD40L costimulatory pathway in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 53 (2004): 1035-1043.

- Bretscher PA. A two-step, two-signal model for the primary activation of precursor helper T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96 (1999): 185-190.

- Bishop GA, Moore CR, Xie P, Stunz LL, Kraus ZJ. TRAF proteins in CD40 signaling. Adv Exp Med Biol 597 (2007): 131-151.

- Zirlik A, Bavendiek U, Libby P, et al. TRAF-1, -2, -3, -5, and -6 are induced in atherosclerotic plaques and differentially mediate proinflammatory functions of CD40L in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27 (2007): 1101-1107.

- Schonbeck U, Mach F, Bonnefoy JY, Loppnow H, Flad HD, Libby P. Ligation of CD40 activates interleukin 1beta-converting enzyme (caspase-1) activity in vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells and promotes elaboration of active interleukin 1beta. J Biol Chem 272 (1997): 19569-19574.

- Mach, François, Uwe Schönbeck, and Peter Libby. CD40 signaling in vascular cells: a key role in atherosclerosis?. Atherosclerosis 137 (1998): S89-S95.

- Mach F, Schonbeck U, Sukhova GK, Atkinson E, Libby P. Reduction of atherosclerosis in mice by inhibition of CD40 signalling. Nature 394 (1998): 200-203.

- Schonbeck U, Sukhova GK, Shimizu K, Mach F, Libby P. Inhibition of CD40 signaling limits evolution of established atherosclerosis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97 (2000): 7458-7463.

- Schonbeck U, Libby P. CD40 signaling and plaque instability. Circ Res 89 (2001): 1092-1103.

- Kusters PJH, Seijkens TTP, Beckers L, et al. CD40L Deficiency Protects Against Aneurysm Formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 38 (2018): 1076-1085.

- Patelis N, Moris D, Schizas D, et al. Animal models in the research of abdominal aortic aneurysms development 66 (2017): 899-915.