The Ongoing COVID-19 Epidemic Curves Indicate an Initial Point Spread in China with Log-Normal Distribution of New Cases Per Day, with A Predictable Last Date of The Outbreak Version 4: Predictions for Selected European Countries, USA, and The World as A Whole, and Try to Predict The End of The Outbreak, Including A Discussion of A Possible “New Normal”

Article Information

Stefan Olsson*, 1,2 and Jing Zhang1

1State Key Laboratory of Agricultural and Forestry Biosecurity, College of Plant Protection

2Plant Immunity Center, Haixia Institute of Science and Technology, College of Life Science

*Corresponding Author: Stefan Olsson, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, No.15 Shangxiadian Road, Cangshan District, Fuzhou City, Fujian Province, China

Received: 01 December 2025; Accepted: 08 December 2025; Published: 15 December 2025

Citation: Stefan Olsson and Jing Zhang. The Ongoing COVID-19 Epidemic Curves Indicate an Initial Point Spread in China with Log-Normal Distribution of New Cases Per Day, with A Predictable Last Date of The Outbreak Version 4: Predictions for Selected European Countries, USA, and The World as A Whole, and Try to Predict The End of The Outbreak, Including A Discussion of A Possible “New Normal”. Fortune Journal of Health Sciences. 8 (2025): 1160-1169.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

During an epidemic outbreak, it is useful for planners and responsible authorities to be able to plan to estimate when an outbreak of an epidemic is likely to ease and when the last case can be predicted in their area of responsibility. Theoretically, this could be done for a point source epidemic using epidemic curve forecasting. The extensive data now coming out of China makes it possible to test if this can be done using MS Excel, a standard spreadsheet program available in most offices. The available data is divided up for China as a whole and the different provinces. This and the high number of cases, and the daily updates made the analysis possible. Data for new confirmed infections for Hubei, Hubei outside Wuhan, China, excluding Hubei as well as Zhejiang and Fujian provinces, all follow a log-normal distribution that can be used to make a rough estimate for the date of the last new confirmed cases in respective areas (v1 published at bioRxiv. In the v2 (bioRxiv) continuation work, 9 additional days were added for the Chinese data to evaluate the previous predictions, supporting the usefulness of the simple technique and testing the feasibility for a non-specialist to make similar predictions using data from South Korea, then available. In v2, the predictions for V2 were evaluated for South Korea and fit well with the beginning of the decline, but in South Korea, it seemed to be difficult to go below 100 new cases per day; potential reasons for this are discussed. To further evaluate when a prediction becomes reliable, the Chinese data was used to evaluate making predictions for each day around the peak in the number of cases to pinpoint when a prediction of the end of a point outbreak is reliable, and that is after2-3 consecutive days of decreasing new cases per day. In v3 (bioRxiv), data for Italy were used to make further predictions for that country. A second new analysis was added to use the fitted equation to detect when the acceleration of new cases per day stopped increasing exponentially. In China, this measured point coincides with the date of the complete Hubei lockdown, and in the new Italian analysis, it coincides with the mandatory Italian lockdown. In this version, v4 (bioRxiv), we expand the analysis to selected European countries, the USA, and the World as a whole. Now, 5 years later, we further discuss the apparent success of the used techniques that might work as a “new normal” with a preparedness to stop secondary outbreaks of COVID-19, as well as to better counteract future COVIDs that are sure to come in an interconnected world with fast travel between countries and between large population centres.

Keywords

COVID-19, Point spread, Predictions and evaluation, Subsequent preprints for evaluation

COVID-19 articles, Point spread articles, Predictions and evaluation articles, Subsequent preprints for evaluation articles.

Article Details

Introduction

In epidemics starting as a point source, the number of new cases often follows a log-normal distribution or a Poisson-Gamma distribution (Gonzales-Barron and Butler, 2011). How this distribution will develop over time can be determined by fitting a log-normal distribution equation to the data for new cases per day that are reported. The estimate will, of course, be more accurate the further into the outbreak. A literal “breaking point” for the accuracy of the estimate for the end of the outbreak comes just after the number of new cases per day has reached its peak. From then on, the estimate should be better and better. Here, a simple method that could be used by local health officials without access to special resources to reliably estimate the time the outbreak ends just after the peak in new cases per day has been reached is presented, using data mainly from the ongoing COVID-19 epidemic in China as a test for its suitability. Methodologically, we published our predictions as preprints at bioRxiv with intervals and used the subsequent analysis at a later time point to test the previous prediction to get a series of analyses that are “timestamped” with their publication date as evidence that the predictions were not made post facto.

Results and discussion

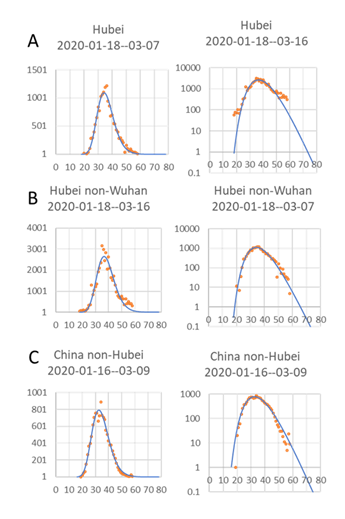

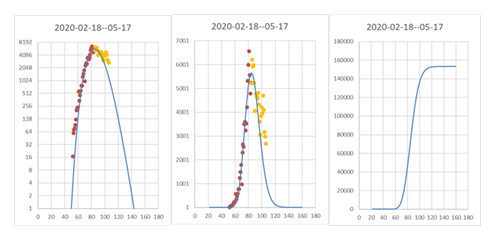

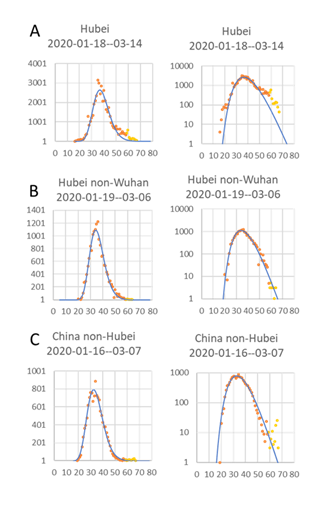

A log-normal distribution can be relatively nicely fitted to all data sets for China (Figs 1&2). When using a log scale for the Y-axis, it is apparent there are deviations in the early dates, especially for Hubei (Fig. 1A). This could be caused by a lag in the detection of new cases at the beginning of the outbreak. The deviations in the latest dates can have many different causes, like changing criteria for new cases, or simply a backlog in case confirmation due to the highly stressed health care system in the worst-hit city, Wuhan. Both the data from Hubei outside Wuhan (Fig. 1B) and China outside Hubei (Fig. 1C), on the other hand, closely follow a log-normal distribution. V1:To see if the same relationships hold also outside Hubei, two provinces with quite different numbers of cases, Zhejiang with many cases, and Fujian with few cases, were also tested (Fig. 2).

Figure 1: Log normal distribution of new confirmed cases for each day since 1 Jan 2020 to mid March 2020, Hubei, Hubei-nonWuhan, and in rest of China. The Log of day values, with start on the first day a case could have been confirmed, was used for curve fitting, although here in the plot, the actual number of days since 1st January was used as the X-axis. Number of new confirmed cases per day and fitted curve (left) and Log number of new cases per day to show start and stop days (right). Headings show estimated dates for the 1st and last cases. The Y-axis, both to the left and right, starts at 1 to highlight the first and last predicted case.

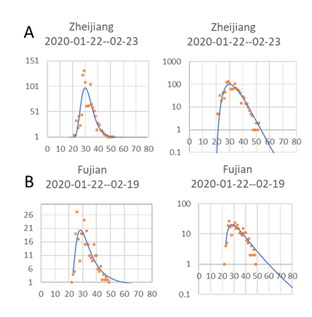

In Zhejiang, the outbreak followed the general pattern very closely (Fig. 2A), but for the much smaller outbreak in Fujian (Fig. 2B), the number of cases per day dropped more than the model did for the last days. This is caused by the approximation to a log-normal distribution instead of a Poisson distribution, which is more correct for data with few cases (Gonzales-Barron and Butler, 2011) but more difficult to handle using standard Excel curve fitting. This discrepancy means that the last new infection date will be overestimated, especially for limited outbreaks like the one in Fujian province. From a planning point of view, it should, however, be safer to overestimate the length of the outbreak than underestimate it. A fairly good estimate of the last data could be done as soon as the number of new confirmed cases per day started to decrease at the inflection point for the sigmoidal cumulative curve of cases.

Figure 2: Log normal distribution of new confirmed cases for each day, 1 Jan 2020 to the end of February, in two provinces, Zeijiang with relatively high numbers of cases with high numbers, and Fujian with low numbers. The Log of day values, with start on the first day a case could have been confirmed, was used for curve fitting, although here in the plot, the actual number of days since 1st January was used as X-axis, and Log number of new cases per day to better show start and stop days (right). Headings show estimated dates for the 1st and last confirmed cases. Y-axis values both to the left and right start at 1 to highlight the first and last case.

The estimated start date for when new cases could have been confirmed, caused by community spread, was for Hubei and Wuhan on the 18th January, while outside Hubei, the data indicate a 2-day earlier start if the disease behaved similarly. This is a bit surprising, but could indicate that the disease was brought to Wuhan city and Hubei province from a less populated area and found good conditions for spread in Wuhan. The estimated start dates for when new cases could be confirmed in the two provinces, Zhejiang and Fujian, were both the 22nd January, only a few days later than in the epicenter for the Chinese outbreak.

V2: Test 9 days later to see if the predictions were reasonable

In the follow-up test of the original prediction, the new data for the next 9 days follow the prediction (Fig. 1) surprisingly well (Fig. 1 continued). This applies to all three cases, but especially good was the prediction for Hubei non-Wuhan (Fig. 1B continued). Interestingly, for China, non-Hubei, which previously seemed to predict a later end date than the data indicated (Fig. 1C), now, with the new data, it is apparent that this is not the case (Fig. 1C continued). Finally, for Hubei, the decrease in new cases for the additional dates in principle follows the shape of the fitted curve but with a slight lag (Fig. 1A continued)

Figure 1: Follow up on the development seen in Figure 1 V1 to evaluate the predictions made previously. Same data and same data-fitting as in Figure 1 in manuscript V1, but with new data from February 27 to March 07 added (yellow dots). The Log of day values, with start on the first day a case could have been confirmed, was used for curve fitting, although here in the plot, the actual number of days since 1st January was used as the X-axis. Number of new confirmed cases per day and fitted curve (left) and Log number of new cases per day to better show start and stop days (right). Headings show estimated dates for the 1st and last confirmed cases. Y values both to the left and right start at 1 to highlight the first and last predicted case.

Test if the MS Excel sheets with the instructions can be used by a non-bioinformatician

The Excel sheet was sent to a previous master student now living in another city (now also a co-author) to test the feasibility of using the sheets to do curve-fitting and predictions using the MS Excel file. After some initial problems like finding out how to find the Solver Add-In for an iMac version of MsExcel things went smoothly. The problem was solved by the master student through an internet search for how to find and add the Solver Add-in to the iMac version. Also, the South Korea data could then be efficiently modelled using the same approach (Fig. 3).

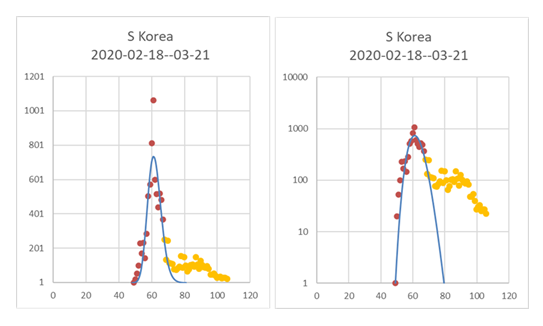

Figure 3: South Korea with follow-up on the development seen in Figure 3 V2 to evaluate the predictions made previously. The Log of day values, with start on the first day a case could have been confirmed, was used for curve fitting, although here in the plot, the actual number of days since 1st January was used as X-axis. Same data and same data-fitting as in Figure 3 in manuscript V2, but with new data from March 7 to April 15 added (yellow dots). Number of new confirmed cases per day and fitted curve (left) and Log number of new cases per day to better show start and stop days (right). Headings show estimated dates for the 1st and last confirmed cases. Y values both to the left and right start at 1 to highlight the first and last predicted case.

Test 27 days later if predictions for S Korea were reasonable.

The first 3-4 days follow the predicted curve very closely, but the latest points stop declining at the level of about 100 new cases per day. There can be many explanations for this. One could be that the restrictions in S Korea were not a complete lockdown as in China, allowing a low-level spread that maintains the levels of new infection at 100 new cases per day. It could also be that in these cases are new infected cases that are leaking in from abroad. South Korea is not in the same situation as China was initially, with basically no cases outside China, or, of course, a combination of both. In the April 15 (Version 4 of the manuscript) it became obvious that the difficulties to decrease below 100 new cases per day most likely depended on the cases entering S. Korea from the rest of world (excluding China) since there came a second small “hump” around end of March (Day 85-92) when the increase was as greatest in the rest of the world (Fig 7).

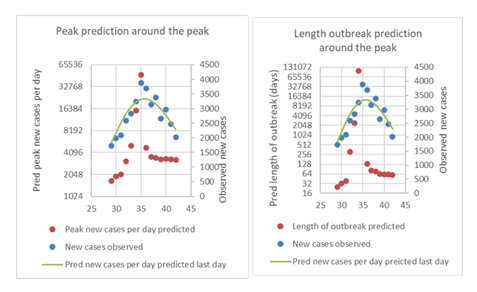

Test when in an outbreak, the predictions become reliable.

We have stated in the previous versions of the manuscript that one needs to wait until or after the peak in new confirmed cases per day for the predictions to be reliable. Now we use the data for China to test this notion. We thus made predictions for consecutive days just before and after the peak in numbers per day. Thus, we can plot curves showing these predictions and compare with where in the curve the predictions were made (Fig. 4). It is apparent that for the China data that 2-3 days of decrease in numbers were needed to be able to reliably predict the magnitude and end of the outbreak (Fig. 4).

Left: Prediction of peak height using the data around the peak, starting some days before the peak and finishing some days after the peak. The left Y axis shows a log scale for the predictions (red dots), and the right Y-axis shows unlogged values for the observed values (blue dots), as well as the predicted fitted equation from the first to the last day (day 42). The actual number of days since 1st January was used as the X-axis

Right: Same as the left figure, here with the predicted length of the outbreak from the predicted first to last case instead of peak height. The prediction of the length of the outbreak becomes reliable just after the peak of new cases.

Use of the fitted equation to determine when the outbreak starts to slow down, increasing in the number of new cases per day, for then later to reach the peak: Use on China data and on Italy data

An equation like the normal distribution has an increasing acceleration phase, a slowdown of the increase of acceleration, then maximum acceleration before going into a deceleration towards the peak. Thus, the point where the acceleration of this acceleration starts to break is the point where something could have happened that determined the whole outbreak size and duration. To determine this, the change in predicted new cases from one day to the next (in principle, the derivative of the equation) was plotted together with the predicted number of cases for the whole outbreak (Fig.5, Left). As can be seen in the figure, the acceleration of the acceleration (the red curve) starts to slow down at day 28 (January 28), and the grid has been adjusted so that it can be seen more easily in the figure. A similar analysis was performed for the Italian data (Fig. 5, right) where it can be seen that the acceleration of the acceleration stops at day 70 (March 10). The Italian prediction data as of March 24 is also presented together with observed data (Fig. 6).

Values for whole mainland China (left) show that the Acceleration of the acceleration in new cases per day started to slow down on day 28 (January 28) (thus the unusual X axis tick values to show that point with grid lines). Values predicted for Italy (right) show a similar change on day 70 (March 10). Left Y axes show increases in the numbers of new cases per day, and right Y axes show new cases per day. The X-axis is days since the start of the year 2020, and the X-axis scale is adjusted so that a vertical gridline passes through the red curves when the number of new cases stops accelerating for China and Italy, respectively.

As can be seen for Italy, new cases are predicted to start falling at around March 24-25, and the outbreak is predicted to reach its last case on May 23 if the present measures by the Italian government are kept. With even stronger measures or an earlier start, this could maybe have been shortened, and the total number of cases would have become lower. If measures are relaxed, the whole outbreak becomes longer, and the total number of cases increases.

The Log of day values with start on the first day a case could have been confirmed was used for curve fitting, although here in the plot, the actual number of days since 1st January was used as the X-axis. Same data and same data-fitting as in Figure 1 in manuscript V3, but with new data (V4) from March 24 to April 15 added (yellow dots). Log number of new cases per day to show start and stop days (left), number of new confirmed cases per day and fitted curve (Middle), and cumulative predicted curve (right). Headings show estimated dates for the 1st and last confirmed cases. Y y-axis in both the left plot and the middle plot starts at 1 to highlight the first and last predicted case.

Test 22 days later, to see if the predictions for Italy were reasonable.

It was apparently a bit too early in the curve on 24th March (Fig. 6) to accurately predict the shape of the curve. The prediction underestimated the number of new cases after that date and thus also underestimates the likely length of the outbreak. The difference is not large but clearly visible in that the new data are clearly above the curve (Fig. 6, yellow dots). A new prediction that better reflects the datapoints was made (Fig. 7), and now the predicted end of the outbreak is June 8 instead of May 17. Thus, the total length of the outbreak is predicted to be 113 days instead of 94 as previously predicted (Fig. 6)

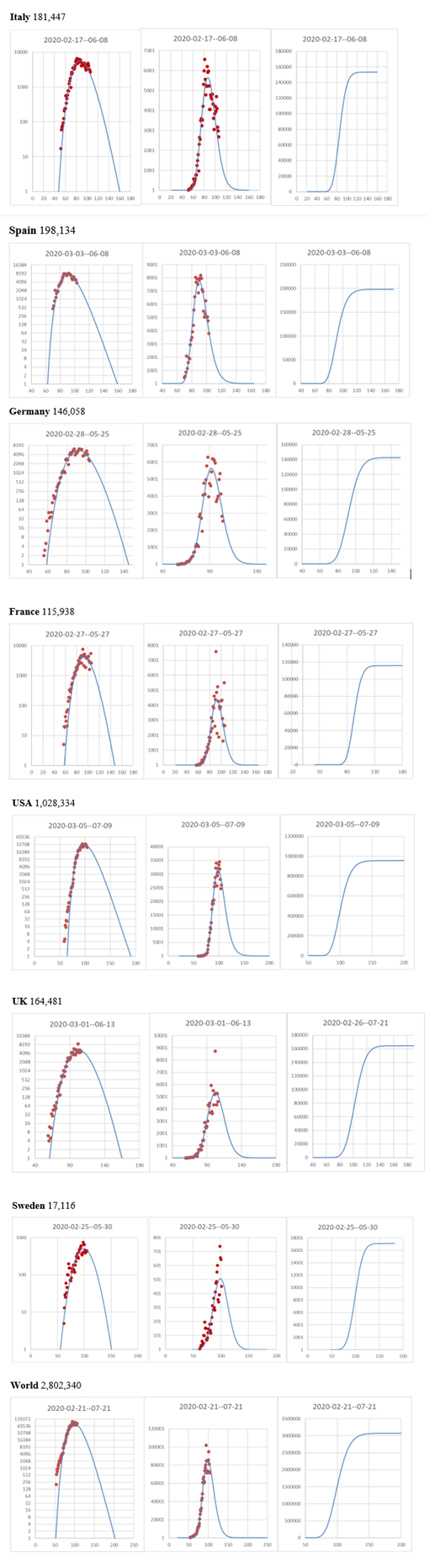

Predicting the COVID-19 outbreak in selected European countries, the USA, and the World.

The pandemic has spread to almost all countries in the world. After some initial uncertainties and delays, most countries have enforced lockdowns or encouraged social distancing and, in effect, tried to limit the spread of COVID-19. In most countries, this is done using a combination of social distancing, testing, and tracing contacts. From the data of April 15, 2020, this actually seems to work (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Log-normal distribution of new confirmed cases for each day since 1 Jan 2020. Some European countries, the USA, and the World. The Log of day values, with start on the first day a case could have been confirmed, was used for curve fitting, although here in the plot, the actual number of days since 1st January was used as X-axis. Number of new confirmed cases per day and fitted curve (left) and Log number of new cases per day to show start and stop days (right). Headings show estimated dates for the 1st and last confirmed case. The log Y-axes start at 1 to highlight the predicted first and last case. To the right of each set of figures name of the country or region and the predicted total number of confirmed cases in each country or region for 2020. Plots for countries are ordered from top to bottom in order of security of prediction, with the top countries being more secure when it comes to outbreak length and total number of registered cases.

It is also obvious from Fig. 7 that the outbreaks can be modelled using the same type of equation. From our predictions, it looked like the initial COVID-19 outbreak could be over in Europe and the USA already in July-August 2020, and in the World maybe at roughly the same time.

The day the acceleration of cases stopped was the day lockdowns were enforced.

Since January 28 for China and March 10 for Italy mark the day when the outbreaks took a new direction, according to our analysis and the acceleration of the acceleration of new cases started to slow down we decided to look up that day in the WiKi-pages (Anonymous, 2020a) that also records the decisions taken by officials to see if anything unusual happened those days. For China, the mandatory lockdown of Hubei was announced the January 28, and the lockdown was in effect on the 29th. For Italy, the lockdown was similarly introduced on March 10. This may point to the importance of an early lockdown, as in China, since it took effect when there were around 1000-1500 new cases per day. In Italy, the same did not happen until there were more than 2000 new cases per day, only 2-3 days later in the outbreak began. This difference seems to double the length of the outbreak and triple the total number of cases compared to China (Fig. 6).

Conclusion

Plotting new confirmed cases per day against time can be used during a large point source epidemic outbreak to relatively early after the peak in new cases, to determine a likely last date for new cases. Such information should be useful to people in charge of planning how to allocate resources. The information will also be available when resources are as most stretched with a large number of active cases just after the peak in number of new cases per day, In addition, if the data continue to fit the curve for a point source outbreak in one area there has most likely been no new introduction of cases or any change to the virus or the likelihood that a person becomes infected within that area. The latter seems to be the case for the COVID-19 outbreak in China 2019-2020, pointing to that the quarantine measures stopping further spread between provinces and cities after the first few days of person-to-person transfer have worked efficiently. The way we do the curve fitting in Solver relies mostly on the more reliable observations with more cases close to the peak of new infections. In the extended work (V2), we tested the predictions for the 9 following days in the previous preprint paper against the new data that had become available, and we found that the technique managed to predict the new data very well. In addition, we have now also found that it is feasible to put the Excel file in the hands of a non-bioinformatician and get useful results, as can be seen for the added figures for South Korea (Fig. 3).

In the further extended work (V3), we evaluated the predictions previously made for South Korea and found that the predictions were valid, but the inflow of cases from other countries and some minor outbreaks and/or not strong enough measures might make it difficult to get the outbreak to completely disappear. We had in V3 added an analysis for when the prediction using our method becomes reliable. That happens a few days after the peak when the number of infections per day starts to decline. We also in V3 added an analysis of when new infections per day stopped accelerating at the same rate. We then found that it was rather early in the China case and only some days later for Italy. To our big surprise, both these dates coincide with the days mandatory lockdown took effect in both countries. The lockdown in Italy, a few days later than the outbreak in China, is also a probable cause of the higher peak in cases and was predicted to result in a 2 times longer outbreak with 3 times higher numbers of total cases than was the case for China. Thus, a few days' hesitation in taking the lockdown decisions appears to have had huge effects.

In the further extended work (V4), we analyzed the outbreaks in selected Western European countries and the USA, and also tried to predict the outcome for the world. To our great surprise, many different types of lockdowns and social distancing seem to work to end the initial outbreaks. The epidemic curves have roughly the same shapes and seem to become very predictable. As we pointed out in the V3, the timing of the lockdown or advice to socially distance appears to be crucial for the number of cases. It is also obvious that the social distancing measures can be very different in different countries and still work depending on the density of people and their culture and social distancing. Prof Olsson, originally from Sweden, was critical of the very light measures taken in Sweden, but thought it might actually work. Sweden has no dense population, and compared to many other countries in Europe and especially in Asia, social distancing is normal behaviour, except among young people anyway. On top of that, most old people in Sweden live at home in their very good flats and houses until the last months of their lives. Thus, there are only a few people in old people’s homes per population today in Sweden. Socially, maybe this is not so good, but definitely an advantage with COVID-19 in society. Many of the initial problems in the old people's homes in Sweden were caused by unprepared and not well-educated personnel and a fragmented organization with no clear responsibilities (Anonymous, 2020b). The World predictions were a bit unsure, but measures to break the transmission of the virus had already been taken in all large countries of the world, so the world predictions were not very far off after all, initially under 2020, when measures to control the disease were rather strict in most countries.

Conclusion 2025

If the world prediction had come through and measures had stayed vigilant until the virus mutated to a less virulent variety or a vaccine became available, that would have been fantastic and encouraging for the future. With the techniques available, temperature checks where people gather and other places in society, combined with compulsory testing if someone is detected with fever and tracing (that can be made anonymous and voluntary) with the help of mobile applications, it should be possible to return to a “new normal” not very different from before the outbreake of the disease, also without a vaccine available as in most of China in the initial phase. These modern technologies, IR fever checks, mobile phone tracing, and PCR-testing might make it possible not just to keep COVID-19 under control but also to early detect and control next COVIDs without a too rushed development of vaccines that take time to prove to be safe enough. Even then, vaccines are not always very efficient and can sometimes cause negative side effects in some people. Next COVID could potentially be much worse and not wait 100 years to appear, so it would be good to quickly develop a “new normal” when that happens, that mainly relies on fast responding measures locally combined with free, compulsory, and efficient testing before being allowed onto trains and flights between provinces in China or countries in Europe. These measures could include nationwide social distancing only when necessary, but the measures have to be strict enough to have a stopping effect. Such a “new normal,” if well designed, should also be able to catch other contagious respiratory tract diseases and limit their spread, including the seasonal influenza and colds, and limit their negative effects on society and be economically sound for society in the long run. It is also obvious from studies that dry indoor air, during the winter heating period (Dec-Feb) and summer AC (Jul-Aug), has aided the spread of the virus. Indoor humidity control, preferably by indoor plants that catch dust as well, could potentially alleviate virus spread of coronaviruses as well as many other viruses (Wolkoff, 2024). Thus, much more could have been done in preparation for contagious respiratory disease outbreaks to limit the damage to society and individuals. This is not the first time we have had a coronavirus spreading worldwide and causing havoc, just the most recent, and we will get it again, maybe even this century, so we have to remember, learn, and plan to be able to behave more rationally next time. The previous time a coronavirus spread around the world was probably the so-called Russian flu that resulted in similar symptoms and was problematic for three consecutive years in the 1890s before the virus eventually seem to have evolved to become less harmful, even if more contagious, and more people became symptomless carriers, and it joined the ‘common cold coronaviruses’ causing seasonal colds (Berche, 2022). This seems to have happened also with the latest Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causing the COVID-19 pandemic (Brüssow and Brüssow, 2021; Berche, 2022; Erkoreka et al., 2022).

Professor Olsson’s personal societal reflections 5 years later (autumn 2025)

Economics of lockdowns, politics, national prestige, vaccination, vaccines, vaccine patents, and confusion about the role of antiviral medication, vaccines, and how coronaviruses spread, severely confused the issues and made it impossible to continue and follow up predictions for 2021 and later, as I had planned to do for the rest of the world outside China. Protecting yourself from society (use of masks mainly intended to protect health care personnel) or protecting society from myself (the surgical masks obligation in China), personal risk, or community risks became mixed in the debate and difficult to understand for the layman. The evolving situation with what was “true” yesterday is not “true” today, reflecting the new situation and the evolving knowledge at the edge of knowledge often goes two steps forward, retracts a step before proceeding forward again, and so on, driven by the last experiences of many, and rumors that could be true or not true. On top of that, virus-specific issues as non-symptomatic spread of respiratory viruses of the coronavirus type, and technical issues as overly sensitive PCR tests labeling people positive when no negligible risk of spreading the virus. A common belief held among the public and politicians was that vaccination could completely stop the spread of the disease, when it mainly limits the chances of serious illness and death in the vaccinated. Diminished trust in science has become the result, due to all conflicting messages being unavoidable in the new situation, but was severely worsened by national and commercial biases since favouring/trusting the own nation's researchers, and pharmaceutical companies for political and economic reasons was rampant. Taken as a whole, the pandemic raged for several years and resulted in an estimated 700 million registered as infected and 7 million deaths as of April 13, 2024, when Worldometer stopped registering https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Thus, 1% of the registered as infected died in the whole world. The figures for China and a few other countries were much more encouraging, and only a fraction of that, although China has a high population and dense population centers and a population that normally travels a lot over large distances during the Spring festival each year to visit relatives, they also did so in 2020 (Zhu and Guo, 2021).

Methods

Official data referred to for the COVID-19 outbreak was collected on Wikipedia pages (Anonymous, 2020c, 2020a). Data for Sweden was not well updated on these pages, so these data were collected from the official Swedish Government page (Folkhälsomyndigheten, Sweden, n.d.). World data was not available on the Wikipedia pages, so it was obtained from Worldometer (Worldometer, n.d.). Since the kind of analysis here presented is a relatively simple analysis, it should be possible to do for anyone using a standard program, Microsoft Excel, with the standard available Solver plugin for data handling and curve fitting. The logarithm of the number of days since the estimated start of the epidemic outbreak was used for fitting a normal distribution equation to the data, but in the figures, the data was plotted against the non-logged day number with day 1 on the 1st January to ease in determining the actual dates from readings on the X-axis and the values in the spreadsheet files. The MS Excel file used for this analysis is available as a Supplementary file and can easily be modified to be used with other data, to relatively early after the peak in new confirmed cases be able to predict the end of an epidemic outbreak with a definite predicted starting with a “first case”.

Acknowledgement

When back to my home country, Sweden, in 2020, I had to decide when it was safe for me, as an over-60-year-old, to return to China after the winter break for the Chinese New Year (Spring Festival). I rightly feared that when cases became common outside China, I would not be able to get back to my work. I decided to look at the epidemiology data since I have been working with biological control, trying to cause epidemics in fungal pathogens attacking plants. I thought of looking for data about the COVID-19 outbreak to be able to determine a time and a route back to my University in Fuzhou, Fujian province, which limits the chances for me to catch the infection and bring it to my workplace. I found the very good Wikipedia entry I refer to in the methods, and would like to thank everyone who has contributed to that site. Finally, I want to acknowledge my employer, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, which makes it possible for me to do molecular and microbiological research in China. I originally thought the outbreaks should be short and stop within about half a year, as had been the case for similar recent outbreaks of coronaviruses. I had not counted on that I could not go back to Sweden until 2022, but then that was ok to do after I had been vaccinated in the summer of 2021 and taken the required tests before getting onto the plane. I have since then had COVID-19 at least once in Sweden in early autumn 2022, but only as a common cold. But that seriously delayed my return to China since I tested positive before the flight, and there were still restrictions. I have probably had it several times more since then, especially in 2023 when restrictions and compulsory tests in China were stopped. But then, I probably had it without symptoms, as many people around me, especially health care workers, had their colds diagnosed as Covid-19.

Supplemental files

“Corona model final.V3.xlsx” is a supplemental file containing all previous data for China with an added Sheet for the Whole of China. This sheet contains prediction reliability data and the data for calculating and showing the acceleration of the number of cases per day. In addition, the file also contains instructions for how to use it to fit new data to make predictions.

“Corona model only S-Korea and Italy.V4” is a supplemental file containing the previous data sheet from V3, with the previous prediction fit to new data. This file also contains data for Italy used for a fitting and prediction similar to what was done for the Whole of China in the other Supplemental file “Corona model final.V3.xlsx”.

“Corona model Europe, US, and World.V4” is a supplemental file containing predictions for the size and the end of the outbreaks for Italy, Spain, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Sweden, the USA, and the World.

Reference

- Anonymous. 2019-20 coronavirus pandemic. WikipediA (2020a).

- Anonymous. Summary-of-sou-2020_80-elderly-care-during-the-pandemic (2020b).

- Anonymous. Timeline of the 2019-20 coronavirus outbreak. WikipediA (2020c).

- Berche P. The enigma of the 1889 Russian flu pandemic: A coronavirus? La Presse Médicale 51 (2022): 104111.

- Brüssow H and Brüssow L. Clinical evidence that the pandemic from 1889 to 1891 commonly called the Russian flu might have been an earlier coronavirus pandemic. Microbial Biotechnology 14 (2021): 1860-1870.

- Erkoreka A, Hernando-Pérez J and Ayllon J. Coronavirus as the Possible Causative Agent of the 1889-1894 Pandemic. Infectious Disease Reports 14 (2022): 453-469.

- Folkhälsomyndigheten, Sweden (n.d.). Bekräftade fall i Sverige - daglig uppdatering (2020).

- Gonzales-Barron U and Butler F. A comparison between the discrete Poisson-gamma and Poisson-lognormal distributions to characterise microbial counts in foods. Food Control 22 (2011): 1279-1286.

- Wolkoff P. Indoor air humidity revisited: Impact on acute symptoms, work productivity, and risk of influenza and COVID-19 infection. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 256 (2024): 114313.

- Worldometer (n.d.). Coronavirus Worldwide Graphs (2020).

- Zhu P and Guo Y. The role of high-speed rail and air travel in the spread of COVID-19 in China. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 42 (2021): 102097.