The Non-Angioblastic Cellular Contribution to Human Meniscal Healing; An Ex vivo Study

Article Information

Lanny L. Johnson, M.D.1*, Gretchen Flo, D.V.M.2, David A. Detrisac, M.D., P.3 Linden Dillin, M.D.4

1President, Pcabioscience, LLC, 445 West 22nd Street, Holland, MI 49423, USA

2Flo, Professor, College of Veterinary Medicine, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

3Detrisac. Private practice Lansing, 3394 E Jolly Rd Suite A, Lansing, MI, USA

4Dillion, Private Practice, Fort Worth TX, USA

*Corresponding Author: Lanny L. Johnson, President, Pcabioscience, LLC, 445 West 22nd Street, Holland, MI 49423, USA.

Received: 14 January 2026; Accepted: 21 January 2026; Published: 28 January 2026

Citation: Lanny L. Johnson, Gretchen Flo, David A. Detrisac, P. Linden Dillin. The Non-Angioblastic Cellular Contribution to Human Meniscal Healing; An Ex vivo Study. Journal of Orthopedics and Sports Medicine. 8 (2026): 11-19.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Objective: The objective of this study was to identify the non-angioblastic sources of cellular contributions to meniscal repair.

Background: Preservation of the knee joint meniscus is a time honored need to prevent osteoarthritis. The vascular supply of the meniscus is limited to the outer one-third. Successful repairs are limited to this area. Repairs in the avascular portion are limited to selected cases. Independent of the region the common denominator of a successful surgical repair of the meniscus is the secure fixation and contact of the two portions. Therefore, multiple biological adjuncts have been advanced to enhance success of meniscus repair. Independent of these ideas healing remains based upon the innate biological tissue and fluids response to injury and surgery. Following bleeding the blood clot is populated with cells. Cellularity presence in the joint is a main contributor to healing. The purpose of this ex vivo study was to identify the source of the non-angioblastic cellular contribution using the same human’s meniscus and fluids.

Methods: Human meniscus and patient blood and synovial fluid from the same person were harvested at time of meniscectomy. The meniscus was cut into five sections. Each section had a core lesion in the center replicating a vascular access channel. Each of the five specimens was placed in separate container with one of the following fluids, normal saline, patient’s plasma, patient’s blood, patient’s synovial fluid aspirate and mixture of blood and synovial fluid. They were cultured for 12 weeks. The specimens were then subject to histological examination.

Results: There was no contribution of cells to from the normal saline or plasma. Meniscal cells remained viable, but no proliferation was observed. The patient’s synovial fluid and blood contributed to the cellularity on the cut edges of the meniscus specimens. The core lesion resulted in loss of meniscal substance and cells in the adjacent area. No meniscal cells were seen to be released or proliferated from the disrupted meniscus. Most of the cellularity was observed from the application of the aspiration of the normal response to injury, a spontaneous mixture of blood and synovial fluid. The host meniscus cells did not appear to contribute any new cellularity.

Conclusions: This human ex vivo study showed the potential for the patient’s body fluids of blood and synovial fluid from the same patient to be potential cellular contributors to meniscal healing and resultant preservation.

Keywords

Human meniscus; Meniscus preservation; Cellularity; Healing; Ex vivo

Article Details

1. Background

It is time honored to understand that preservation of the knee joint meniscus is critical to prevention of osteoarthritis or its progression [1-3]. When possible, meniscus repair is to be favored over meniscectomy.

However, knowing only the outer rim of the meniscus adjacent to the synovial wall has vascularity restricts the optimal repair to peripheral longitudinal tears. Therefore, an intraoperative decision remains concerning removal of a torn meniscus and or repair in the non-vascular area [4].

Second look documentation after arthroscopic meniscal repair support the choice of meniscus repair in selected cases. [5,6]

The common denominator of success in meniscus repair is the secure fixation and apposition of the meniscus tissue [7].

The challenge remains of obtaining a successful repair in the avascular portion of the meniscus. Additional methods have been advanced to secure healing. Robinson et al. [8] reviewed the multiple other means of assisting meniscal repair, i.e. no augmentation, trephination, rasping, marrow venting, fibrin clot, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) and meniscal wrapping [8].

Chirichella et al. [9] reported on the use of orthobiologics such as platelet-rich plasma and mesenchymal stem cells have shown promise in augmenting surgical repairs or as standalone treatments, although research for their use in meniscal tear management is limited.

Wang et al. [10] introduced the hyaluronic acid hydrogel as an adjunct to meniscus repair.

Arnoczky and Warren [11] demonstrated the importance of the vascular contribution to peripheral meniscus tear repair. The vessels were found to originate in the peripheral capsular and synovial tissues. Peripheral meniscal tears adjacent to the capsular and synovial vascularity are more likely to heal. Joint capsule synovium may contribute to peripheral meniscal tears. Penetration was into 25% of the avascular inner meniscus. However, not all experimental lesions healed. They cautioned that their animal results were not a substitute for human clinical evidence [11].

Arnoczky and Warren’s [11] observation of the meniscal microvascular prompted the idea of a surgical procedure of cutting a channel in the avascular meniscus to bring vascularity into the avascular portion of the meniscus to promote healing. This was accomplished by cutting a channel from the vascularized periphery across the tear and into the avascular meniscus. Others reported on similar ways to introduce vascularity into the avascular meniscus [11-14].

Having postulated the importance of the fibrin clot from revascularization Arnoczky et al. [15] then studied the effect of the fibrin clot to the repair process. Two-millimeter cores were created in the avascular inner margin of the meniscus by open incision. They then studied the non-angioblastic or cellular contribution to meniscal healing in dogs. Subsequent pathological studies between two and twenty-six weeks showed non-angioblastic cellular repair. At two weeks there were fibrocytes. At four weeks the tissue was more fibrous. At six weeks there was a homogenous matrix populated with two cell types. On the surface they were elongated, and in the matrix the cells were ovoid. At twelve weeks the translucent tissue was histologically more cartilaginous. At six months the tissue resembled fibrocartilage. This established a timeline for healing in clinical management. Polarized light microscopy showed the presence of collagen. The fibrin clot appeared to act as a chemotactic and mitogenic stimulus for reparative cells and to provide a scaffolding for the reparative process.They showed that fibrin clots populated with cells act as a temporary biologic scaffold. They demonstrated cell migration into the meniscus from the clot. They confirmed failure of healing when cellular clot formation was prevented, supporting our observation of the necessity of “hold and held”. The holes without fibrin clot showed no healing. The origin of the repair cells was not clear.

Independent of the many biological augmentation methods advocated for meniscus repair success is dependent a secure fixation and the host’s biological response to injury and or surgery.

The fundamentals of healing in the synovial joint are no different than elsewhere; bleeding and blood clot formation occurs following injury and or surgery to initiate the repair.

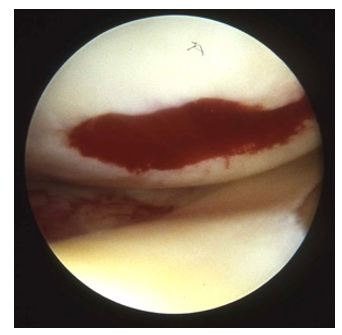

A fibrin clot is arthroscopically observed on the traumatic or surgically interrupted surface of the synovial joint (Figure 1). The contribution to healing is dependent upon the fibrin clot being “housed and held” in place long enough for the healing events to occur [16].

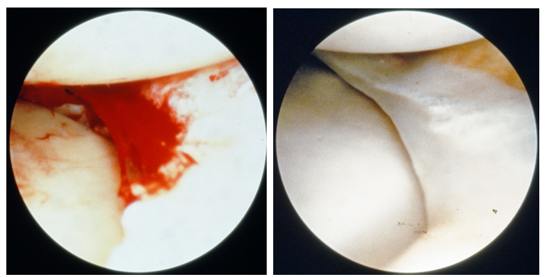

Meniscal tissue regeneration has been observed on the inner margins of the retained meniscus following partial meniscectomy [17]. Blood clots have been seen to attach to the surgically resected edge of a meniscus (Figure 2a). Subsequent opportunistic arthroscopic documentation in other cases showed the site of the previous resection to be a fibrous tissue replacement (Figure 2b).

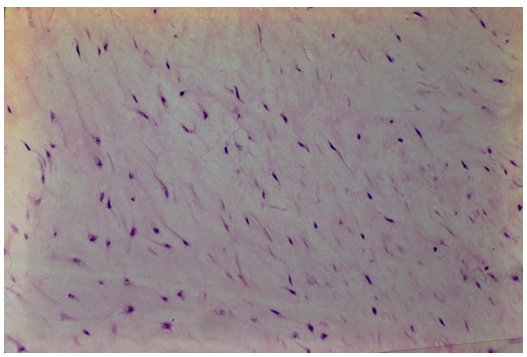

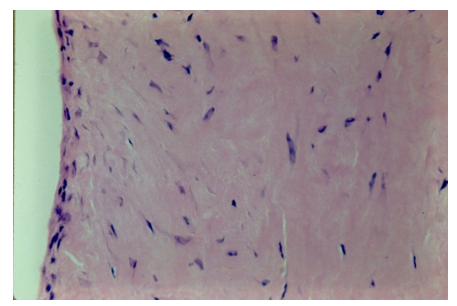

A biopsy of the regenerated tissue on the meniscus shows an avascular cellular matrix on the intact and viable host meniscus (Figure 3). High power photomicrograph of the regenerated tissue shows no vascularity only cellular proliferation.

The source of the cellularity in the regenerated meniscus has not been defined. The meniscus is not likely as source of cellular contribution to a repair because of the few cells widely dispersed in the matrix. McNulty AL et al. [18] observed meniscal tears in mature rabbits did not have a meniscal cellular response [18].

Meniscal cells may contribute to providing there is growth factor stimulation [19].

The purpose of this study was to explore the intraarticular source of the cellularity that has potential to populate the blood clots and produce biological healing for the human meniscus. The date of this study in 1986 preceded Investigational Review Boards. However, the patients were aware of the use of the removed tissue and granted permission following informed consent. The following ex vivo experiment was performed.

2. Materials and Methods

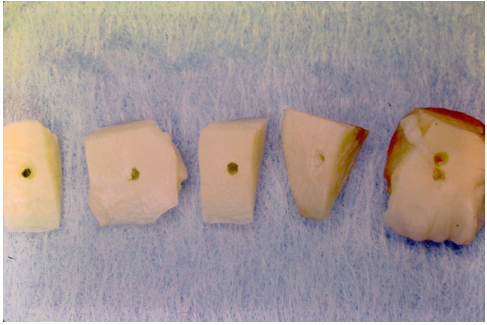

Between April 17, 1985, and January 22, 1986, there were 23 arthroscopic cases and one total knee surgery performed at the Ingham Medical Center, Lansing, Michigan from which the meniscus specimens were harvested. These patients also contributed their peripheral blood and synovial fluid aspirate at the time of surgery. The surgeries were performed by the senior author at Ingham Medical Center, Lansing, Michigan. The resected meniscus was of sufficient amount to provide for multiple sections for five separate and different tissue culture mediums (Figure 4).

There were 15 males and 9 females from which the meniscal tissue was harvested. The average age of the patients was 34 years. The range of age was 14 to 70 years. There were 17 medial meniscal tears, 3 lateral tears and 4 involving both menisci. The bucket handle and longitudinal tears were most suitable for the study. The tears existed by patient history between 4 weeks and 14 years. The longer time was the specimen from the total joint.

The human meniscal pathological specimens were sectioned vertically into approximately 5.0-millimeter squares (Figure 4). A 2.0-millimeter core was created in the center of the specimen with a Jamshidi biopsy needle (Benton, Dickinson and company) to replicate a vascular access channel (Figure 4). The sterile specimens were placed in a divided culture dish and covered with five different cellular holding fluids; normal saline, patient’s plasma, patient’s blood, synovial fluid and a mixture of blood and synovial fluid when that had naturally occurred. Initially 3-inch Petri dishes were used for the specimens. This resulted in increased space requirements, more culture media, plus handling. Photography was taken at intervals of the specimens in the culture medium. The few specimens having fungal contamination were discarded. Changing to a six-pocket rectangular container, plus greater emphasis on sterility and deferring photography until after the culture period eliminated the chance of subsequent contamination.

There were five separate fluid environments: saline, patient’s plasma, patient’s blood, patient’s synovial fluid, and mixture of synovial fluid and blood (Figure 5). The various fluid environments were labeled and easily identified making the subsequent cellular responses to each possible by histological examination. The saline provided no nutrients or potential cellular source of repair. This environment provided the best opportunity to observe the activity of the meniscal cells. The plasma was expected to provide nutrition and no cells. Plasma provided an opportunity to learn of the contribution of nutritional potential to meniscal cellular activity. The synovial fluid was expected to contain both free synovial cells and white blood cells as potential cellular source. The whole blood has red blood cells, white blood cells, fibrinogen and growth factors. The mixture of synovial fluid and whole blood had potential to provide many cells. The mixtures of blood and synovial fluid were of two types. One was from the natural mixture occurring from the injury. The other was mixture of the two fluids after aspiration which was achieved by placing one after the other on the meniscus specimen. In retrospect, mixing in the syringe prior to application would have given a replication of the natural blending of the fluids. The patient’s fluids provided the opportunity to observe the potential cellularity contribution to meniscal repair not from vascular proliferation.

The fluid application to the specimens was done between one to three hours after harvest which was at the conclusion of the surgery. The specimens at room or environmental temperature in containers were transported across town by automobile to the tissue culture laboratory at the Michigan State College of Human Medicine.

The experimental technique was like that reported by Becker, et al while studying intrinsic tendon cell proliferation [20].

Dulbecco’s MEM (minimal essential media) low dextrose, 15% calf serum, plus antibiotics (penicillin 100 units, streptomycin 100 mg per 1 milliliter) was added one to three hours after arrival at the laboratory. The environment was then at 37 degrees Celsius and had 5% CO2.

Initially the five meniscal specimens from each patient were subject to each of the five fluid biological environments. Later in the study when realized the normal saline and or plasma yielded no cells, only those with cellularity potential were utilized, blood, synovial fluid and the mixture. The purpose was to increase the number of specimens with potential cellular repair.

The meniscus tissue was removed from culture between three weeks and three months. The specimens were placed in buffered formalin solution. They were processed for histology and subjected to histological staining with Hematoxylin and Eosin and placed on glass slide preparation for microscopic examination.

Histological inspection of the meniscal tissue from each of the culture mediums was performed. Attention was given to the viability and cellularity of the host meniscal tissue. Recording was made of the nature of the cellularity; normal, hypocellular, sparsity or absent. The two types of incisional margins made on the meniscus during preparation were examined. One was the lacerations on each side to create the specimen. The other was the core lesion created by pushing the Jamshidi needle through the meniscus replicating vascular access channeling. The remaining surface was the intact inner meniscal margin, unviolated during surgery or preparation.

The various surfaces were inspected for meniscal cellularity, tissue integrity and meniscal viability. Observations were made for sites of cellularity. Observations were made for additional cellular activity from the meniscus itself or the various autogenous biological patient matched additives, blood, synovial cells and a mixture.

3. Results

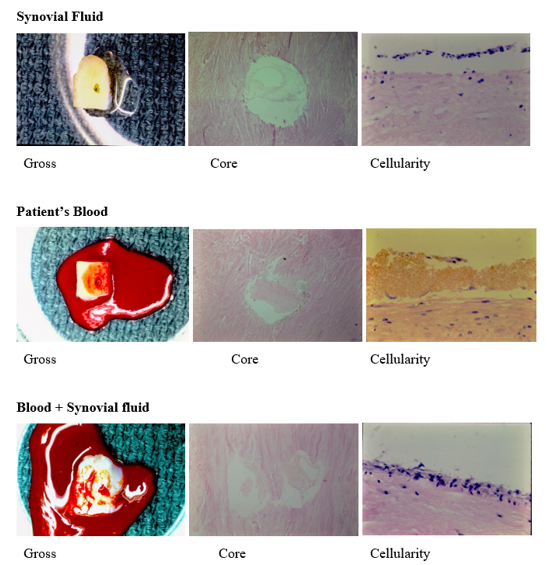

The results are summarized in Table 1. All available specimens were tabulated according to the initial fluid environment. Several original specimens were lost to contamination. The photographs and microphotographs of the three solutions that produced cellularity are shown in Figure 5.

The gross specimens were off white in color except for those coated with blood (Figure 4). They appeared brown after three weeks in culture media following exposure to air and oxidation. The core of the specimens cultured in synovial fluid, blood and mixture of the two showed a clear substance within. There were few cells in what perhaps was a proteaceous material. Its biological nature was not examined.

Histological inspection showed the meniscus specimens in saline had no repair or meniscal cellular response (Figure 6a). However, meniscal cells did exist and remain alive in three of the five specimens away from the core disruption of tissue (Table 1).

There was no meniscal cellularity or around the core lesion of the meniscus seen in the specimens subject to the patient’s plasma (Figure 6b). However, all specimens showed normal meniscal cellularity away from the lesion after six weeks in the plasma culture media (Table 1).

|

Initial Environment |

Repair Cells |

Meniscus |

||||||

|

(N) |

Surface |

Core |

None |

Alive |

Hypo |

Rare |

Dead |

|

|

Saline |

8 |

- |

- |

8 |

2 |

1 |

- |

5 |

|

Plasma |

6 |

- |

- |

6 |

6 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Synovial Fluid |

31 |

19 |

(5) |

12 |

18 |

3 |

4 |

6 |

|

Blood |

56 |

37 |

(13) |

13 |

26 |

14 |

3 |

13 |

|

Natural Mixture |

6 |

6 |

(6) |

6 |

||||

|

Post op Mixed |

5 |

2 |

- |

3 |

2 |

- |

- |

3 |

Table 1: The post-operative artificial mixtures of blood and synovial fluid results were not comparable to the natural spontaneous mixture.

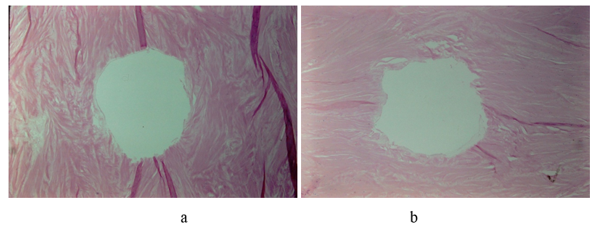

Nineteen of the 31 specimens subject initially to only the patient’s synovial fluid showed repair cells on the surface (Figure 5). In five instances there was cellularity in or covering the core defect (Figure 7a). In mixture of blood and synovial fluid there was greater amount cellularity in the clot of the core defect (Figure 7b).

Figure 7: a: Photomicrograph of minimal cellularity attached to the surface of the disrupted meniscus tissue adjacent to the core lesion. There was occasional meniscal cell observed but no evidence suggesting cellular proliferation or continuity to the cellularity on the surface. b: Photomicrograph of abundant cellularity in the core defect in blood/synovial fluid environment.

The meniscal tissue remained viable in eighteen, hypocellular in 3, rare cells in 4 and no cells in 6 (dead). The absence of meniscal cells was not related to the presence of repair cellularity from the synovial fluid. In other words, repair cells existed even when the meniscus specimen was acellular, and presumable non-viable. Conversely the presence of cells in the meniscus substance did not insure existence of repair cells.

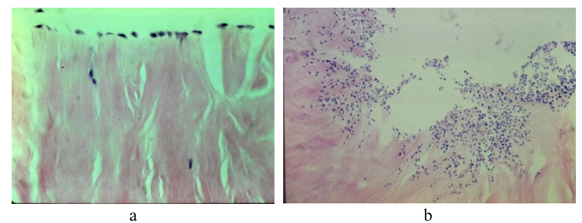

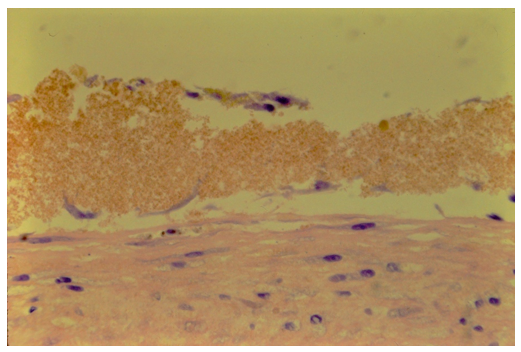

There were 56 meniscal specimens available for study after initial application of only the patient’s blood, followed by tissue culture (Figure 5). Thirteen showed cells in the central core area (Figure 7). The meniscal tissue remained cellular in 26, hypocellular in 14, sparse cellularity in 3 and no cells in the meniscal specimen in thirteen (Table 1).

The cellularity contribution from the fluid existed even when there were no cells in the adjacent host meniscus (Figure 5). This is further evidence the meniscus cells were not contributing to the cellularity.

The cellular response to the margins with a sharp laceration differed from those produced by the Yamshiti needle on the core lesions. The laceration showed no tissue crush or loss of adjacent meniscal cells. The core margins showed fragmentation of tissue structure and loss of cellularity around the defect that was created by pressure and rotation during the cutting (Figure 5-7). The cellular response was minimal in and around the core defects margins. This differed from the greater cellular response adjacent to a sharp laceration (Figure 8).

There was minimal cellularity response on the intact normal meniscus surface. Thirty-seven specimens showed histological evidence of cellularity repair on the normal meniscus surface. The lacerated meniscus surface showed histological evidence of cellular repair but no adjacent evidence of meniscal cellular proliferation contribution (Figure 9).

The natural biological response to injury of the joint aspirate of blood and synovial fluid mixture (n=6) showed cellularity produced on the surface and in the core in all cases (Figure 5,7,8). The meniscus was viable in all cases.

4. Discussion

The unpublished original manuscript and illustrations of this study was recently found in the office archives of the senior author. The original methods, materials and results are unchanged. The 35-millimeter photographs were in good condition and digitalized. The references have been updated and therefore the discussion is contemporary.

The possible origins of the cellularity for meniscal repair process are the vascular angioblasts, the migration of the synovial cellular lining, the meniscal cells, the synovial fluid and blood. The vascular angioblasts and the synovial cellular lining were excluded as sources in this study design. However, the potential for cellular contribution from the meniscus, synovial fluid and blood were examined and identified.

The response of a synovial joint to injury or surgery results in bleeding and blood clot formation. There is a contributory cellularity is from the presence of synovial fluid, blood and or the combination thereof. In this ex vivo study cellularity attached to every disrupted surface. Unlike Arnozcky and Warren’s work in animals, the patient’s meniscal tissue did not show any proliferation of cells and or contribution to the surface cellularity [15]. This was consistent with McNulty et al. observations [18]. The cellular contribution was from the patient’s synovial fluid and blood or the combination thereof.

The natural mixture of whole blood and synovial fluid following injury or the surgery was aspirated from the patient’s knee joint in this study. This natural mixture produced the most robust cellularity (Figure 5). This natural mixture although small in numbers (n=6) showed retention of host meniscal tissue viability. The post operative artificial physical combining blood with synovial fluid in a syringe did not produce comparable results Table 1.

The potential of whole blood’s growth-factor contributions to meniscal repair were outside the assessments in this study. Additional aids in meniscal healing reported since 1986 were not evaluated [21].

Fibrin clots occurred, but the importance of the fibrin clot in meniscal repair reported by Arnoczky and Warren was observed but not assessed in this study [15]. Growth factors were not included in this study.

Monocytes are important to the healing process. They may leave the circulation, enter the tissue and become macrophages and affect meniscal repair. These factors, although not measured in this study may affect the meniscal repair process. In vivo experiments including using diffusion chamber in subcutaneous tissue of animals has shown the differentiation of monocytes to fibroblasts [22-25]. Similar observations have been made with the epidural injection of autogenous blood for post puncture headache [26].

Whole blood produced a cellular response. Specimens showed a thin layer of red blood cells on the meniscus with repair cells on that cellular displaced form the meniscus (Figure 8). In the absence of vascular angioblasts, tissue other than meniscus, or synovial fluid, the origin of this cellularity is presumed to be the circulating monocytes in whole blood.

Synovial fluid represents a plasma ultrafiltrate to which a hyaluronic protein complex has been added. Ogilvie-Harris et al. [27] reported that in joint aspiration in cases of chronic torn meniscus showed free synovial cells (12%) and monocytes (14%) plus many lymphocytes (43-70%). There are also polymorphonucleocytes varying with the inflammatory response. No red blood cells are seen in chronic cases [27].

Synovial proliferation contributes to healing of the adjacent meniscus but was outside the parameters of the methodology of this study which was looking only for free cells [28].

Free synovial cells have been reported to contributing to the non-angioblastic cellular response in tendon repair. They have been the source of the non-angioblastic cells in Hennerbichler et al. [29] study, but the source was not identified.

Synovial cells have been reported to contribute to articular cartilage repair [30-33].

The natural mixture of blood and synovial fluid aspirate from the knee joint produced a more robust cellular response that a mixture made artificially (Figure 5 and Table 1).

Carefully crafted in vitro studies by Webber et al. showed that extracted meniscal cells have the potential to proliferate and contribute to a cellular repair [34]. Meniscal cells remained in situ in this present study.

An in situ meniscal cellular response was not seen in this study design. There was intact meniscus with cells, but no proliferation of meniscal cells adjacent to the incisions (Figure 5). The area of core cut physically fragmented the adjacent tissue such that if possible meniscal cells would have been released (Figure 7). No or few meniscal cells were seen as if released. In addition, there was a loss of meniscal cells in the body of the meniscus adjacent to the core injury. There was cellularity on the fragmented meniscus adjacent to the core lesion (Figure 7). There were sparse meniscal cells adjacent to the core lesion as the injury disrupted host meniscal substance for some distance (Figure 7). When only the patient’s blood was applied to the meniscus specimens there was a layer of blood cells between the meniscus and the new cellularity (Figure 8). There was no evidence of proliferation of meniscal cells migrating outside the meniscus or migration through the red blood layer as to contribute to that cellularity in the non-angioblastic cellular envelope.

The natural meniscal surface affected the cellular layer attachment showing cellularity. The cleanly incised surface consistently showed the repair layer of cellularity (Figure 5,8,9). The area of crushed tissue around the core had minimal cellularity (Figure 7a). In addition, the crushed area was void of meniscal cells some distance from the inner margin of the core meniscal injury (Figure 7a). Even when repair cells were in abundance adjacent to the fragmented meniscal substance of the core lesion there was no repair during the length of this study (Figure 7b). There was no evidence of meniscal cellular proliferation, clumping, or mitotic activity.

The clinical significance shown in this ex vivo study showed the biological insult to the meniscus from a core lesion replicating that made vascular access channel. The core lesion produced meniscal fragmentation, absence of cells in the meniscus but cellularity adjacent (Figure 5,7). This is contrasted with a sharp incision which resulted in less meniscal cellular loss in the adjacent substance and less tissue disruption. There is an abundant, uniform cellular response to the clean incision of the human meniscus (Figure 5,7).

The multiple non-angioblastic sources of cellularity identified herein provides the potential for meniscal repair. This study did not examine the clinical practice of vascular channels per se but did show a replica of a vascular channel with the core defect lesion. The core defect surface in the human meniscus explants showed cellularity on a disrupted surface of meniscal substance (Figure 7). The core lesion resulted in crush of tissue that resulted in adjacent meniscal cellular death. The synovial fluid and patient’s blood clot provided a biological environment inducive to cellular attachment to all disrupted surfaces.

The vascular channel may also create as mechanical stress riser vulnerable to future rupture or tear. The vascular access channel concept probably is not necessary for human meniscal healing as the mixture of blood clot and the spontaneous cellularity are naturally present following injury and surgery. For these reasons vascular access channels may be contraindicated in the human as Arnoczky and Warren cautioned. They recognized the tissue disruption and cautioned against creating vascular access channels (trephination) because doing so can disrupt the circumferential collagen fiber architecture of the meniscus, which may weaken its structural integrity and predispose it to tearing or failure rather than reliably improving healing [11].

The strength of this study was an ex vivo experimental design that replicated the biological environment which would occur naturally following injury and or surgery. The design combined the same human’s meniscus and biological fluids. Each human meniscus tissue was exposed to the fluids from the same patient, plasma, whole blood and synovial fluid. This study showed the potential for the non-angioblastic cellular contribution of three normal resident joint fluids to meniscal repair. This report highlighted the importance of blood and blood clot to meniscal healing. The designed compared the results of cellular response to two types of meniscal cuts, a crush of a core lesion and a sharp incision. The sharp incision attracted cellularity and retained viability of the adjacent meniscus. The core crush lesion replicating a vascular access channel showed few if any host meniscal cells in the disrupted host meniscus. There was cellularity adjacent to the crush lesion, but no evidence of repair. There was a minimal cellularity response on the intact meniscus surface.

The limitations of this study were that it did not examine the totality of the contributions to the meniscal healing. The various growth factors that have potential effect on meniscal healing were not evaluated. The study design did not include synovium which is source of anabolic factors. The biological anabolic reagents known in blood and synovium were not measured. Available potential anabolic therapeutic reagents were not evaluated, i.e., platelet derived growth factors or bone marrow aspirate. These factors may be focus of future studies. The study was not long enough or by design to see the final contribution of the non-angioblastic cellularity on the mature healing response of the meniscus. The photomicrographs were without dates but those showing blood or cells without organization were the 3-week specimens. The magnification of the photomicrographs was not available. The old documents had only one reference to magnification. It was possible to recalculate for the 2 mm core lesion photomicrographs which were 10-12 millimeters in the photomicrographs which would make them at 5 or 6X power.

5. Clinical Relevance

The focus was on meniscal preservation. The clinical relevance was the demonstration there is abundant cellularity in situ to assist the healing of a repaired meniscus in the avascular zone. There was abundant cellularity available in situ to populate the local blood clot. Attention was drawn to the importance of a blood clot to healing, one that was housed and held in place (Figure 1,2). The natural biological response to meniscal injury and or surgery is intraarticular bleeding combined with synovial fluid which produces abundant cellularity potential for meniscal repair. The cellularity is present for additional surgical measures to facilitate meniscal repair [8-10]. The meniscal damage produced by a core lesion probably outweighs any benefit from vascular access channels. The host meniscus cells are an unlikely spontaneous natural contribution to meniscal repair [18]. Therefore, the emphasis was on the other sources of cellularity.

6. Future Studies

Future studies should continue to focus upon the preservation of the meniscus. They should be extended to include preservation of the meniscus in degenerative arthritis of the knee where arthroscopic debridement procedures alone have limited benefit [35]. A future similar ex vivo study should have specimens from the arthritic total knee surgery in which the synovium has continuity with the meniscus specimens. This future experimental model would include the adjacent non vascularized synovium’s potential contribution to meniscal healing and or preservation [30-33].

More importantly an anabolic reagent’s potential should be considered as an adjunct to treatment in meniscus preservation [21]. Protocatechuic acid (PCA) is one such anabolic reagent. PCA was discovered since the time of this study in 1986. PCA by the oral route had anabolic effects on the synovial joint of the mammal. Dose related protocatechuic acid (PCA) increased the anabolic cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 and the growth hormone IFG-1 in the mammalian knee joint. In addition, PCA increased the lubricin on the articular cartilage surface while increasing the aggrecan and type II collagen in the articular cartilage matrix. The anabolic effect on the meniscus in degenerative arthritis is yet to be studied.

US patent # 11, 980, 635, May 14, 2024. Methods of oral administration of protocatechuic acid for treating or reducing the severity of a joint injury or disease.

Acknowledgements

Robert Bull D.V.M, a major contributor to this study was deceased in 2003. Drs. Flo, Detrisac and Dillion participated in the design, execution, and writing of the manuscript. The funding was from the senior author.

Potential conflicts of interest

Dr. Johnson is holder of US patent # 11, 980, 635 and owner of Pcabioscience, LLC that markets a commercial product of PCA sold at www.drlannyhealth.com. Drs. Flo, Detrisac and Dillion have no financial interest or conflict of interest.

References

- Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 16 (1957): 494-502.

- Roos H, Laurén M, Adalberth T, et al. Knee osteoarthritis after meniscectomy: prevalence of radiographic changes after twenty-one years, compared with matched controls. Arthritis Rheum 41 (1998): 687-693.

- Patil SS, Shekhar A, Tapasvi SR. Meniscal preservation is important for the knee joint. Indian J Orthop 51 (2017): 576-587.

- Mahardika IG, Aryana IGNW. Functional outcome of meniscus repair compared to meniscectomy for meniscus tear: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med 13 (2025).

- Dai W, Leng X, Wang J, et al. Second-look arthroscopic evaluation of healing rates after arthroscopic repair of meniscal tears. Orthop J Sports Med 9 (2021).

- Chand SB, Santhosh G, Saseendran A, et al. Efficacy and long-term outcomes of arthroscopic meniscus repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus 16 (2024).

- Bachmaier S, Krych AJ, Smith PA, et al. Primary fixation and cyclic performance of meniscal repair devices. Am J Sports Med 50 (2022): 2705-2713.

- Robinson J, Murray IR, Moatshe G, et al. Current practice of biologic augmentation techniques to enhance healing of meniscal repairs. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc (2025).

- Chirichella PS, Jow S, Iacono S, et al. Treatment of knee meniscus pathology: rehabilitation, surgery, and orthobiologics. PM R 11 (2019): 292-308.

- Wang G, Liu XJ, Zhang XA, et al. Advances in hyaluronic acid hydrogel for meniscus repair. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 13 (2025).

- Arnoczky SP, Warren RF. The microvasculature of the meniscus and its response to injury. Am J Sports Med 11 (1983): 131-141.

- Gershuni DH, Skyhar MJ, Danzig LA, et al. Experimental models to promote healing of tears in the avascular segment of canine knee menisci. J Bone Joint Surg Am 71 (1989): 1363-1370.

- Zhang ZN, Tu KY, Xu YK, et al. Treatment of longitudinal injuries in avascular area of meniscus in dogs by trephination. Arthroscopy 4 (1988): 151-159.

- Longo UG, Campi S, Romeo G, et al. Biological strategies to enhance healing of the avascular area of the meniscus. Stem Cells Int 2012 (2012).

- Arnoczky SP, Warren RF, Spivak JM. Meniscal repair using an exogenous fibrin clot. J Bone Joint Surg Am 70 (1988): 1209-1217.

- Johnson LL. Characteristics of the immediate post arthroscopic blood clot formation in the knee joint. Arthroscopy 7 (1991): 14-23.

- Johnson LL. Arthroscopic surgery: principles and practice. Mosby (1986).

- McNulty AL, et al. Meniscal cell responses to injury. J Orthop Res 38 (2020): 800-812.

- Melrose J, Smith S, Cake M, et al. Meniscal cells have the capacity for intrinsic matrix repair. J Anat 213 (2008): 694-705.

- Becker H, Graham MF, Cohen IK, et al. Intrinsic tendon cell proliferation in tissue culture. J Hand Surg Am 6 (1981): 616-619.

- Ishida K. Platelet-rich plasma promotes human meniscal cell proliferation. J Orthop Res 25 (2007): 861-866.

- Petrakis NL, Davis M, Lucia SOP. In vivo differentiation of human leukocytes. Blood 17 (1961): 109-118.

- Volkman A. The origin and fate of the monocyte. Ser Haematol 3 (1970): 62-92.

- Allgower M, Hulliger L. Origin of fibroblast from mononuclear blood cells. Surgery 47 (1960): 603-612.

- Grillo HC. Origin of fibroblasts in wound healing. Ann Surg (1963).

- DiGiovanni AJ, Galber MW, Wahle WM. Epidural injection of autologous blood for postlumbar puncture headache. Anesth Analg (1972).

- Ogilvie-Harris DJ, McLean J. Synovial fluid analysis in internal derangements of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br 64 (1982): 208-212.

- Hennerbichler A, et al. Repair response of the meniscus to rim and non-rim tears. Am J Sports Med 35 (2007): 754-762.

- Hatsushika D, et al. Repair of meniscal lesions using synovial mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 31 (2013): 1364-1373.

- Shimomura K, et al. Reparative effect of synovial cells following meniscal injury. J Orthop Res 28 (2010): 1033-1039.

- De Bari C, Dell’Accio F, Tylzanowski P, et al. Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from adult human synovial membrane. Arthritis Rheum 44 (2001): 1928-1942.

- Horie M, Sekiya I, Muneta T, et al. Synovial stem cells promote meniscal regeneration. Stem Cells 27 (2009): 878-887.

- Ozeki N, Kohno Y, Kushida Y, et al. Synovial mesenchymal stem cells promote meniscus repair. J Orthop Res 39 (2021): 177-183.

- Webber RJ, Harris M, Hough AJ Jr, et al. Intrinsic repair capabilities of rabbit meniscal fibrocartilage. Trans Orthop Res Soc 9 (1984): 278.

- Sihvonen R, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med 369 (2013): 2515-2524.