Superficial Tumor Treatment with CyberKnife Device in the Head: An Alternative to Standard Radiation Therapy

Article Information

Anna Ianiro1, Erminia Infusino1*, Marco D’Andrea1, Silvia Takanen2, Laura Marucci2, Francesco Quagliani1, Jacopo Costantini1, Antonella Soriani1

1Medical Physics Unit. IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, Rome, Italy

2Radiation Oncology Unit. IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, Rome, Italy

* Corresponding Author: Erminia Infusino, Medical Physics Unit, Regina Elena National Cancer Institute - IFO, Via Elio Chianesi 53, 00144 Rome, Italy

Received: 06 June 2025; Accepted: 03 July 2025; Published: 05 December 2025

Citation: Anna Ianiro, Erminia Infusino*, Marco D’Andrea, Silvia Takanen, Laura Marucci, Francesco Quagliani, Jacopo Costantini, Antonella Soriani. Superficial Tumor Treatment with CyberKnife Device in the Head: An Alternative to Standard Radiation Therapy Journal of Cancer Science and Clinical Therapeutics 9 (2025): 199-204.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Purpose: The treatment of superficial head tumors with standard linear accelerators (linacs) often requires a bolus and/or multiple non-coplanar beams to increase surface dose and ensure adequate skin coverage. This study evaluates whether the CyberKnife (CK) system can serve as a valid alternative to these conventional methods. Methods: Fourteen patients with superficial tumor in the head were treated at our Institution with CK. All patients were retrospectively re-planned for linac treatment with bolus and in some cases with multiple no-coplanar beams. CK and linac plan quality was evaluated and compared through dose volume histogram (DVH) and dose distribution metrics. Plan deliverability was also verified through 2D gamma analysis. Results: For both techniques, all plans produced gamma pass rates above 90%. Target coverage resulted significantly higher for CK plans, while the volume of brain receiving 95% of prescription dose (V95, brain) was significantly lower. Dose distribution parameters analysis highlighted better conformity and gradient metrics in favor of CK plans, while no difference in homogeneity was noticed. Delivery time for CK plans resulted significantly higher with respect to VMAT plans. Regarding clinical outcome, of the 8 patients that showed at follow-up after 2 years, 7 had total response and 1 had partial response. Conclusions: CyberKnife is a valid alternative for treating superficial head tumors, offering superior dosimetry performance without the need for a bolus. Additionally, CK eliminates the need for couch movements required by non-coplanar linac techniques, improving treatment reproducibility and reducing setup uncertainties.

Keywords

<p>Radiotherapy; Superficial tumors; CyberKnife; Bolus</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

The incidence of skin cancer is increasing worldwide due to factors such as sun exposure, climate change, and photosensitizing conditions [1]. Malignant melanomas (MM) account for only 3% of cases, whereas the vast majority are non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) [2]. Among these, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) represents approximately 25% of cases [3,4]. Despite their generally favorable prognosis, SCCs can exhibit local invasion, recurrence, and even metastasis, highlighting the need for comprehensive research into their molecular mechanisms, risk factors, diagnostic approaches, and therapeutic strategies, particularly in relation to superficial tumors of the head. Other types of cancers affecting the skin are primary cutaneous lymphomas (PCLs) which are a heterogeneous group of B and T-cell lymphomas presenting in the skin without evidence of extracutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis. In the Western world, cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are the most common type of PCL in the form of mycosis fungoides. Most patients with mycosis fungoides have limited stage disease at the time of diagnosis and a favorable prognosis, but skin lesions can appear in variable numbers and gradually spread with a high rate of relapsed/refractory disease following front line therapy [5]. The investigation of an efficient treatment modality is therefore of fundamental importance and must always be considered in a multidisciplinary context. The main goal in the treatment of superficial tumors in the head must be increasingly personalized, providing the maximum oncologic efficacy and the best possible management of collateral effects. Treatment options for superficial tumors in the head include surgery, cryotherapy, electrode dilation and curettage, topical drugs, photodynamic therapy (PDT), and radiation therapy (RT) [6]. Surgery is generally the first treatment option, but it can have disfiguring cosmetic outcomes. For this reason, RT is considered a viable alternative to surgery for the primary treatment of superficial tumors in the head, not only because of its positive cosmetic outcomes [7,8] but also for its high rate of local control. As a result, considerations of functionality, cosmetic outcome, and patient preference may lead RT to treatment of choice, not limited only to patients that are not suitable for surgery or in a postoperative scenario [9]. RT can be administered as external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) with electron, photon or proton beams, or as low dose rate (LDR)/high dose rate (HDR) brachytherapy (BRT) [10]. Often, the primary goal of RT is to relieve symptoms such as pain, bleeding, ulceration, and obstruction caused by the tumor, improving patient’s functions and quality of life. However, RT can be used at any stage of the disease, with curative or palliative intent, as an exclusive, adjuvant treatment or in conjunction with systemic treatments [11-13]. In skin cancer cases, EBRT is usually performed with volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) techniques with standard linacs and requires the use of a specific device, named bolus, able to superficialize the dose and ensure adequate coverage of target surface. Most common bolus consists of a moldable slab of water-like material. In tumors located at head surface, the perfect fitting of the bolus to patient skin is not always achievable due to anatomical irregularities represented for example by ears, nose or eye sockets. Air gaps between the bolus and the skin could severely affect target coverage at the surface and thus treatment reproducibility [14]. Sometimes the use of several non-coplanar beams/arcs can improve target coverage even if the bolus is not employed [15]. In fact, when using multiple accesses, the radiation is delivered in a more tangential manner to every point of the surface, allowing better skin coverage. However, couch motion during the treatment with non-coplanar beams could increase the uncertainty of the body position relative to the couch and thus undermine treatment reproducibility [16]. The CyberKnife device (Accuray Incorporated) is a compact linear accelerator mounted on an industrial robot producing several non-is centric non-coplanar photon beams around the patient [17-19], without requiring significant couch movements. CK is a treatment machine specifically designed for stereotactic treatments that require the administration of high doses in 1-5 fractions. The treatment of superficial lesions, instead, is usually delivered over 25-30 fractions with conventional doses per fraction. However, the use of CK in the treatment of superficial tumors could present some advantages with respect to standard treatments. For example, its multiple accesses beam delivery makes the use of bolus redundant. Moreover, CK is equipped with two orthogonal imaging systems that provide image guidance during the whole treatment process. This tracking system allows the advantage of using tighter margins around the target with an improvement in normal tissue sparing. The aim of this study is to explore and describe our experience in the treatment of superficial tumors in the head with CK. Original CK plans were retrospectively reoptimized, simulating VMAT treatments with standard linacs, using multiple non-coplanar beams and/or virtual bolus. CK and VMAT plans were compared in terms of DVH and dose distribution, to assess the feasibility of CK employment in the treatment of superficial tumors in the head.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. CyberKnife device

CyberKnife–M6 device is a linear accelerator mounted on an industrial robot with a 6-axis manipulator arm, producing 6 MV flattening filter free (FFF) photon beams at a fixed dose rate of 800 MU/min. The device ensures sub-millimetric accuracy, tracking the target position with two orthogonal integrated x-ray imaging systems. CK is provided with three collimator types: (i) 12 fixed collimators, with circular apertures ranging from 5 to 60 mm diameter, defined at 800 mm source-to-axis distance (SAD); (ii) an Iris collimator, composed of 2 hexagonal banks of tungsten segments producing dodecagonal apertures with the same sizes of fixed collimators; (iii) an InCiseTM Multileaf collimator (MLC), with 2 banks of 41 tungsten leaves 2.5 mm wide and 90 mm thick with full interdigitation and overtravel, to create shapes as small as 7.6 × 7.5 mm2, and as large as 100.0 × 97.5 mm2 at 800 mm SAD. Fixed and Iris collimators are particularly suitable for stereotactic treatments such as brain metastases. MLC collimators are more versatile and allows the treatment of targets with irregular shape, like prostate or spine cases. For superficial head tumors cases, MLC collimators were employed.

2.2. Patients

Fourteen patients (median age: 74.5y; range 53-91y) with skin lesions were treated at our Institution with CK device between November 2021 and July 2024. Eleven patients with diagnosis of NMSC had lesions localized at the level of the head region, three patients presented superficial lesions at the level of the scalp and forehead related to mycosis fungoides. Computed tomography (CT) images with a slice thickness of 1.25 mm were acquired using a Philips Big Bore scanner (Koninklijke Philips N.V., Netherlands). Patient setup and immobilization was guaranteed with the use of a short thermoplastic mask. Radiation oncologists contoured the clinical target volume (CTV) and organs at risk (OARs) following standard protocols, using Eclipse treatment planning system (TPS) (Varian Medical Systems, Inc., Palo Alto, USA) version 15.6 to. In CK plans, planning target volume (PTV) was obtained giving a 1.5 mm margin to CTV, while in VMAT plans a 5 mm margin was given. All patients were prescribed with a dose of 60Gy in 30 fractions. Dose inhomogeneity up to 110% of prescription dose inside the target was allowed.

2.3. Treatment planning

CK clinical plans were calculated with the Precision TPS (Accuray Incorporated, Sunnyvale, USA), version 2.0.1.1. The optimization was performed using the VOLO™ optimizer [20-21]. Were possible, beam direction was set to never intersect the eyes and/or the mouth. On average, three shells were used to control the dose gradient around the target. The maximum number of nodes was set at the highest available value, allowing the maximum freedom of movement to the robotic arm. The final dose calculation was performed with the Monte Carlo algorithm, a dose calculation uncertainty of 1%, and high dose grid resolution that corresponds to the CT step (1mm). VMAT plans were calculated with the Raystation TPS (RaySearch, Stockholm, Sweden) version 12A. A virtual bolus with water-like density and 5 mm thickness was added to all patients CTs so as to cover the whole target surface. Beams with a dose rate of 600 MU/min and a photon energy of 6 MV produced by a TrueBeam linear accelerator (Varian Medical Systems Inc., USA) were employed. In some cases, in order to improve target coverage non-coplanar beams were used. For VMAT plans also dose calculation was performed with the Monte Carlo algorithm, a dose calculation uncertainty of 1% and a dose grid resolution of 1.2 mm.

2.4. Delivery Quality Assurance (DQA)

For both CK and VMAT plans, deliverability was assessed with the SRS MapCHECK detector used in combination with StereoPHAN phantom (Sun Nuclear Corp, Melbourne, USA). SRS MapCHECK is a high-density solid-state array of 1013 diodes with sub-millimetric resolution (0.48 mm × 0.48 mm area) and an active area of 77 mm × 77 mm [22-24]. StereoPHAN is a polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) head-shaped phantom with a proper housing to accommodate the detector. The agreement was assessed using the SNC software version 8.3 (Sun Nuclear Corp., Melbourne, USA) by means of 2D gamma analysis, evaluating the percentage of points for which the gamma index is ≤1. A global-pixel-dose difference of 2%, a distance-to-agreement of 2 mm and a gamma pass-rate of 90% criterion was employed.

2.5. Plan comparison

CK and VMAT plan comparison was based on (i) DVH metrics, (ii) plan quality metrics, and (iii) treatment delivery time. Regarding DVH metrics, PTV coverage and the dose to the main OAR, i.e. the brain, were considered. In particular, for PTV the dose received by 95% of volume (D95, PTV) was evaluated. For the brain, the volume receiving 95% of prescription dose (V95, brain) and the organ integral dose, defined by equation 1 [25], were analyzed.

In equation 1, Dmean,brain is the mean dose to the brain expressed in Gy and Vbrain is the brain volume expressed in liters.

Regarding plan quality, we analyzed conformity, homogeneity, and gradient metrics. The Conformation Number (CN) is defined by equation 2 [26].

V100, PTV (cm3) is the target volume receiving the prescription dose, VPTV (cm3) is the total target volume and V100 (cm3) is the body volume receiving the prescription dose. CN is less than or equal to 1, the latter case being the ideal one.

The Homogeneity Index (HI) is defined by equation 3 [27] as the ratio between the maximum point dose in the plan (Dmax) and the prescription dose (PD).

The novel gradient index (NGI50) is described by equation (4) [28].

where V50 (cm3) is the body volume covered by the 50% isodose line.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 29 (SPSS inc., Chicago IL, USA). The continuous variables were reported through means, standard deviations (SD), medians and their min-max range, while categorical variables were reported through absolute frequencies and percentages. The Shapiro-Wilk normality test for all continuous variables was calculated. Differences between continuous variables were assessed with the Mann-Whitney test or Student T test, as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at p-values less than 0.05. Graphical representations were elaborated with RStudio version 4.1.2 (RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA).

3. Results

3.1 Dosimetric analysis

For both CK and VMAT plans, QA verification with SRS MapCHECK system produced gamma pass rates above 90%.

Table 1: shows the results obtained for all parameters analyzed.

Table 1: Comparison between CK and VMAT plans for all metrics analyzed.

|

Technique |

|||

|

CK |

VMAT |

Mann-Whitney test |

|

|

Median (min-max) |

Median (min-max) |

p-value |

|

|

VPTV (cc) |

18,22 (7,37-70,13) |

39,09 (14,15-103,49) |

0,081 |

|

Dmax (cGy) |

6634,00 (6397,00-6897,00) |

6647,00 (6519,00-6832,00) |

0,779* |

|

D95,PTV (cGy) |

5859,00 (5339,00-6100,00) |

5700,00 (5535,00-5753,00) |

<0,001 |

|

V95,brain (cc) |

0,00 (0,00-5,16) |

0,27 (0,00-16,80) |

0,015 |

|

IDbrain (GyL) |

0,34 (0,05-1,11) |

0,42 (0,17-1,40) |

0,435 |

|

CN |

0,68 (0,44-0,89) |

0,53 (0,43-0,67) |

<0,001* |

|

HI |

1,11 (1,07-1,15) |

1,11 (1,09-1,14) |

0,779* |

|

NGI50 |

1,10 (0,39-2,38) |

0,58 (0,24-0,97) |

0,005* |

|

Time (min) |

16,50 (10,00-20,00) |

1,16 (0,57-2,41) |

<0,001 |

3.2. Student T test

D95, PTV differed significantly between the two techniques in favor of CK plans, while no difference in plan Dmax was observed. Regarding the dose to the brain, V95, brain resulted significantly lower for CK plans, although no difference in the ID was evidenced. Dose distribution parameters analysis highlighted higher CN and NGI50 values in CK plans, while no difference in HI was noticed. Delivery time for CK plans resulted also significantly higher with respect to VMAT plans.

3.3. Clinical outcomes

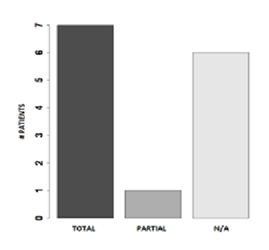

Figure 1 shows clinical results. Eight patients (57%) showed at follow-up (FUP) after 2 years. Of these patients 7 had total response, and 1 had partial response, with a reduction of at least 30% in the sum of diameters of target lesions compared to the baseline diameters sum.

4. Discussion

RT plays a significant role both in curative and palliative settings for skin cancer patients [29-32]. However, the data on its use in terms of modalities or fractions are often quite heterogeneous. In this study, we proposed CK treatments as an alternative to standard linac treatments for patients with superficial tumors in the head. The CK is an advanced robotic radiosurgery system that allows tumours and lesions to be treated with extreme precision while reducing damage to surrounding healthy tissue. Although it is widely used for the treatment of brain, spinal and lung tumours, its use in skin treatments represents an innovative and minimally invasive option for some dermatological diseases. Fourteen patients treated at our Institution with CK device were retrospectively replanned for VMAT treatments. In general, our results suggested that similar plan quality can be achieved on either linac or CK platforms, respecting all dosimetric constraints.

In VMAT plans, target margin was larger than CK (5 mm vs 1.5mm) but no statistical difference between target volumes was observed. However, it should be noted that the choice of the margins used could be affected by individual technology and protocols, thus might vary among Institutions. Dosimetric comparison between CK and VMAT plans evidenced how CK could produce plans with better target coverage (+2.8%) with similar plan Dmax. In addition, we found a significantly higher V95, brain in VMAT plans, likely due to the larger target margin used with respect to CK plans and to the almost always coplanar beam arrangement adopted. CK could produce plans with better conformity (+28.3%) and gradient (+89.7%) metrics thanks to its multiple no-coplanar accesses. Maybe, these results could be achieved also with VMAT plans using several no-coplanar beams. However, whatever the method of non-coplanar VMAT treatment, feasible orientations for non-coplanar beams remain limited in comparison to CK. It should be added that our linac is equipped with a standard MLC with leafs having a 5 mm resolution at isocenter, while CK MLC has 2.5 mm leaf width. A high-definition MLC with a finer leaf width may improve the dose fall-off of VMAT plans and achieve more compact isodoses [33]. CK is a treatment machine specifically designed for stereotactic treatments. There is no prohibition on the use of CK for standard treatments, but it has to be considered that CK plans could require much longer delivery times with respect to standard treatments. Our results showed such difference, with CK plans having a delivery time 14 times higher than VMAT plans. This could represent one of the main limitations when using CK device for the treatment of superficial head tumors patients. However, delivery time comparison between linac and CK can depend on many factors including dose rate, intra-fractional imaging and setup correction. It should be acknowledged that the treatment time, especially for linac delivery, can vary among institutions with different intra-fractional verification protocols and technology. In general, shorter treatment time potentially reduces the effect of intra-treatment tumor motion or baseline drift [34-35]. However, CK systems could be less susceptible to intra-treatment tumor motion from longer treatment time as compared to linacs, due to its real-time motion compensation strategy. Moreover, for patients with skin cancer localized at head surface an immobilization mask is always used, thus reducing possible target motion during the treatment. Instead, it should be emphasized that shorter treatment times may indicate higher dose rates that could potentially increase the incidence of normal tissue toxicity from a radiobiological point of view [36].

In conclusion, the results of this study confirm the efficacy and safety of the analyzed treatment, contributing to the existing literature with new evidence. Data analysis has shown a significant improvement in the clinical parameters of treated patients, supporting the initial hypothesis that this method could represent a valid therapeutic option. Despite the encouraging results, our study presents some limitations. The follow-up duration may not be sufficient to assess the long-term effects of the treatment. Future studies with a prospective design and a larger number of patients could further strengthen the emerging evidence. CyberKnife represents a promising option for treating skin tumors in selected cases, offering a non-invasive alternative to traditional surgery. However, treatment selection should always be evaluated by a multidisciplinary team to ensure the best personalized therapeutic strategy for each patient.

5. Conclusion

The treatment of superficial tumors localized at the head region with CK device is feasible and provides several advantages with respect to standard VMAT treatments. First of all, it ensures the maximum treatment reproducibility since there is no need to use the bolus, and patient positioning is constantly monitored by the tracking system. Moreover, thanks to the tracking system it is possible to use tighter margins around the target with significant improvement in brain sparing. On the other hand, CK treatment time is significantly higher compared to a standard VMAT treatment. In the cost-effectiveness assessment this should be taken into account considering that superficial head tumors treatments are delivered over 30 fractions. The final therapeutic decision should be borne by the radiation oncologist, according to the department workload.

References

- Zaar O, Gillstedt M, Lindelöf B, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma incidence is increasing in Sweden. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 30 (2016): 1708-1713.

- Cives M, Mannavola F, Lospalluti L, et al. Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers: Biological and Clinical Features. Int J Mol Sci 21 (2020): 53-94.

- Apalla Z, Lallas A, Sotiriou E, et al. Epidemiological trends in skin cancer. Dermatol Pract Concept 7 (2017): 01-06.

- Losquadro WD. Anatomy of the Skin and the Pathogenesis of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 25 (2017): 283-289.

- Mourad A, Gniadecki R. Overall Survival in Mycosis Fungoides: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Invest Dermatol 140 (2020): 495-497.

- Mendez BM, Thornton JF. Current Basal and Squamous Cell Skin Cancer Management. Plast Reconstr Surg 142 (2018): 373e-387e.

- Guinot JL, Rembielak A, Perez-Calatayud J, et al.GEC-ESTRO ACROP recommendations in skin brachytherapy. Radiother Oncol 126 (2018): 377-385

- Yu L, Oh C, Shea CR. The Treatment of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer with Image-Guided Superficial Radiation Therapy: An Analysis of 2917 Invasive and In Situ Keratinocytic Carcinoma Lesions. Oncol Ther 9 (2021): 153-166.

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma. National Comprehensive Cancer Network©. Version 1.2023.

- Pashazadeh A, Boese A, Friebe M. Radiation therapy techniques in the treatment of skin cancer: an overview of the current status and outlook. J Dermatolog Treat 30 (2019): 831-839.

- Conforti C, Corneli P, Harwood C, Zalaudek I. Evolving Role of Systemic Therapies in Non-melanoma Skin Cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 31 (2019): 759-768.

- National Comprehensive Cancer N. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Basal Cell Skin Cancer. NCCN.

- Prior P, Awan MJ, Wilson JF, et al. Tumor Control Probability Modeling for Radiation Therapy of Keratinocyte Carcinoma. Front Oncol 11 (2021): 621-641.

- Butson MJ, Cheung T, Yu P, et al. Effects on skin dose from unwanted air gaps under bolus in photon beam radiotherapy. Rad Meas 32 (2000): 201-204.

- Ostheimer C, Janich M, Hübsch P, et al.. The treatment of extensive scalp lesions using coplanar and non-coplanar photon IMRT: a single institution experience. Radiat Oncol 9 (2014): 82.

- Jöhl A, Bogowicz M, Ehrbar S, et al. Body motion during dynamic couch tracking with healthy volunteers. Phys Med Biol 64 (2018): 015001.

- Kuo JS, Yu C, Petrovich Z, et al. The CyberKnife stereotactic radiosurgery system: description, installation, and an initial evaluation of use and functionality. Neurosurgery 53 (2003): 1235-1239.

- Quinn AM. CyberKnife: a robotic radiosurgery system. Clin J. Oncol Nurs 6 (2002): 149-156.

- Bellec J, Delaby N, Jouyaux F, et al. Plan delivery quality assurance for CyberKnife: statistical process control analysis of 350 film-based patient-specific QAs. Phys Med 39 (2017): 50-58.

- Accuray Inc. CyberKnife® Robotic Radiosurgery System. Treatment Planning Manual. Accuray Incorporated.

- Zeverino M, Marguet M, Zulliger C, et al. Novel inverse planning optimization algorithm for robotic radiosurgery: First clinical implementation and dosimetric evaluation. Phys Med 64 (2019): 230-237.

- Rose MS, Tirpak L, Van Casteren K, et al. Multi-institution validation of a new high spatial resolution diode array for SRS and SBRT plan pretreatment quality assurance. Med Phys 47 (2020): 3153-3164.

- Ahmed S, Zhang G, Moros EG, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of the high-resolution diode array for SRS dosimetry. J Appl Clin Med Phys 20 (2019): 13-23.

- Infusino E, Ianiro A, Luppino S, et al. Evaluation of a planar diode matrix for SRS patient-specific QA in comparison with GAFchromic films. J Appl Clin Med Phys 24 (2023): e13947.

- Aoyama H, Westerly DC, Mackie TR, et al. Integral Radiation Dose to Normal Structures with Conformal External Beam Radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 64 (2006): 962-967.

- van't Riet A, Mak AC, Moerland MA, et al. A conformation number to quantify the degree of conformality in brachytherapy and external beam irradiation: application to the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 37 (1997): 731-736.

- Shaw E, Kline R, Gillin M, et al. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group: radiosurgery quality assurance guidelines. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 27 (1993): 1231-1239.

- Shen Z, Luo H, Li S, et al. A novel dose fall-off index and preliminary application in brain and lung stereotactic radiotherapy. Med Phys 50 (2023): 3127-3136.

- Conforti C, Corneli P, Harwood C, et al. Evolving Role of Systemic Therapies in Non-melanoma Skin Cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 31 (2019): 759-768.

- National Comprehensive Cancer N. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Basal Cell Skin Cancer. NCCN

- National Comprehensive Cancer N. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Squamous Cell Skin Cancer.

- Benkhaled S, Van Gestel D, Gomes da Silveira Cauduro C, Palumbo S, Del Marmol V, Desmet A. The State of the Art of Radiotherapy for Non-melanoma Skin Cancer: A Review of the Literature. Front Med (Lausanne) 9 (2022): 913269.

- Sharma DS, Dongre PM, Mhatre V, et al. Physical and dosimetric characteristic of high-definition multileaf collimator (HDMLC) for SRS and IMRT. J Appl Clin Med Phys 12 (2011): 34-75.

- Li W, Purdie TG, Taremi M, et al. Effect of immobilization and performance status on intrafraction motion for stereotactic lung radiotherapy: analysis of 133 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 81 (2011): 1568-1575.

- Zhao B, Yang Y, Li T, et al. Dosimetric effect of intrafraction tumor motion in phase gated lung stereotactic body radiotherapy. Med Phys 39 (2012): 6629-6637.

- Mueller AC, Karam SD. SBRT for Early Stage Larynx: A Go or No Go? It's All in the Delivery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 105 (2019): 119-120.