Small-Cell Lung Cancer in a Cancer Center in Colombia

Article Information

Carlos Carvajal1*, Diego-Felipe Ballén2, Natallie Jurado3, Rafael Beltrán1, Martha-Liliana Alarcón4, Camilo Vallejo-Yepes5, Marcela Nuñez6, Rafael Parra-Medina7, Ricardo Bruge?s-Maya2,8

1Thoracic Surgeon, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Bogotá, Colombia

2Clinical Oncologist, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Bogotá, Colombia

3Clinical Oncology Fellow, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Bogotá, Colombia

4Clinical Oncologist, Hospital Internacional de Colombia, Bucaramanga, Colombia

5Clinical Oncologist, Hospital San Vicente Fundación, Rio Negro, Colombia

6Biostatistician, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Bogotá, Colombia

7Pathologist, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Bogotá, Colombia

8Clinical Oncologist, Hospital Universitario San Ignacio, Centro Javeriano de Oncología, Bogotá, Colombia

*Corresponding Author: Carlos Carvajal, Thoracic Surgeon, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, Bogotá Colombia.

Received: 12 December 2022; Accepted: 23 December 2022; Published: 20 January 2023

Citation: Carlos Carvajal, Diego-Felipe Ballén, Natallie Jurado, Rafael Beltrán, Martha-Liliana Alarcón, Camilo Vallejo-Yepes, Marcela Nuñez, Rafael Parra, Ricardo Brugés-Maya. Small-Cell Lung Cancer in a Cancer Center in Colombia. Journal of Cancer Science and Clinical Therapeutics 7 (2023): 09-15.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Objective: This study aimed to describe the principal clinical features, survival outcomes, and prognostic factors of patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) treated at the Instituto Nacional de Cancerologia (INC) between 2013 and 2018.

Methods: A retrospective analytical study was conducted.

Results: 35 patients with SCLC were included, with a median age of 61 years (IQR=54-71), 24 of which were men (68.6%); 23 patients (65.7%) were admitted with an ECOG score ≤2, and 5 (14.3%) had no smoking history. 26 patients (74.3%) had extended, and 9 (25.7%) had limited disease. Three patients (8.6%) underwent surgical management. Three patients with limited disease received definitive chemotherapy and radiotherapy. 23 (65.7%) patients received best supportive care and 6 (17.1%) patients with extended disease received palliative chemotherapy. The median survival of the entire cohort was 4.5 months (95% CI, 2.56- 8.28). Overall survival (OS) at 1 and 3 years was 26.5% and 5.9%, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier curves showed that patients with an ECOG >2 (p<0.0014), smoking history (p=0.0026), and extended disease (p=0.0035) had a worse OS. The median survival of patients who received chemotherapy, palliative chemotherapy, and best supportive care was 29.0, 11.9, and 2.6 months, respectively. Multivariate analysis showed that the only independent variable for worse OS was ECOG >2 (HR: 2.59, 95% CI, 1.09-6.12, p=0.031).

Conclusions: SCLC has the worst prognosis among all types of lung cancer worldwide. In Colombia, the findings are no different, and additionally, survival was clearly affected in patients with ECOG>2, smoking history, and extended disease.

Keywords

<p>Antineoplastic Agents; Cigarette Smoking; Chemoradiotherapy; Small Cell Lung Carcinoma</p>

Antineoplastic Agents articles; Cigarette Smoking articles; Chemoradiotherapy articles; Small Cell Lung Carcinoma articles

Antineoplastic Agents articles Antineoplastic Agents Research articles Antineoplastic Agents review articles Antineoplastic Agents PubMed articles Antineoplastic Agents PubMed Central articles Antineoplastic Agents 2023 articles Antineoplastic Agents 2024 articles Antineoplastic Agents Scopus articles Antineoplastic Agents impact factor journals Antineoplastic Agents Scopus journals Antineoplastic Agents PubMed journals Antineoplastic Agents medical journals Antineoplastic Agents free journals Antineoplastic Agents best journals Antineoplastic Agents top journals Antineoplastic Agents free medical journals Antineoplastic Agents famous journals Antineoplastic Agents Google Scholar indexed journals Cigarette Smoking articles Cigarette Smoking Research articles Cigarette Smoking review articles Cigarette Smoking PubMed articles Cigarette Smoking PubMed Central articles Cigarette Smoking 2023 articles Cigarette Smoking 2024 articles Cigarette Smoking Scopus articles Cigarette Smoking impact factor journals Cigarette Smoking Scopus journals Cigarette Smoking PubMed journals Cigarette Smoking medical journals Cigarette Smoking free journals Cigarette Smoking best journals Cigarette Smoking top journals Cigarette Smoking free medical journals Cigarette Smoking famous journals Cigarette Smoking Google Scholar indexed journals Chemoradiotherapy articles Chemoradiotherapy Research articles Chemoradiotherapy review articles Chemoradiotherapy PubMed articles Chemoradiotherapy PubMed Central articles Chemoradiotherapy 2023 articles Chemoradiotherapy 2024 articles Chemoradiotherapy Scopus articles Chemoradiotherapy impact factor journals Chemoradiotherapy Scopus journals Chemoradiotherapy PubMed journals Chemoradiotherapy medical journals Chemoradiotherapy free journals Chemoradiotherapy best journals Chemoradiotherapy top journals Chemoradiotherapy free medical journals Chemoradiotherapy famous journals Chemoradiotherapy Google Scholar indexed journals Small Cell Lung Carcinoma articles Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Research articles Small Cell Lung Carcinoma review articles Small Cell Lung Carcinoma PubMed articles Small Cell Lung Carcinoma PubMed Central articles Small Cell Lung Carcinoma 2023 articles Small Cell Lung Carcinoma 2024 articles Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Scopus articles Small Cell Lung Carcinoma impact factor journals Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Scopus journals Small Cell Lung Carcinoma PubMed journals Small Cell Lung Carcinoma medical journals Small Cell Lung Carcinoma free journals Small Cell Lung Carcinoma best journals Small Cell Lung Carcinoma top journals Small Cell Lung Carcinoma free medical journals Small Cell Lung Carcinoma famous journals Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Google Scholar indexed journals lung cancer articles lung cancer Research articles lung cancer review articles lung cancer PubMed articles lung cancer PubMed Central articles lung cancer 2023 articles lung cancer 2024 articles lung cancer Scopus articles lung cancer impact factor journals lung cancer Scopus journals lung cancer PubMed journals lung cancer medical journals lung cancer free journals lung cancer best journals lung cancer top journals lung cancer free medical journals lung cancer famous journals lung cancer Google Scholar indexed journals pancreatic cancer articles pancreatic cancer Research articles pancreatic cancer review articles pancreatic cancer PubMed articles pancreatic cancer PubMed Central articles pancreatic cancer 2023 articles pancreatic cancer 2024 articles pancreatic cancer Scopus articles pancreatic cancer impact factor journals pancreatic cancer Scopus journals pancreatic cancer PubMed journals pancreatic cancer medical journals pancreatic cancer free journals pancreatic cancer best journals pancreatic cancer top journals pancreatic cancer free medical journals pancreatic cancer famous journals pancreatic cancer Google Scholar indexed journals radiotherapy articles radiotherapy Research articles radiotherapy review articles radiotherapy PubMed articles radiotherapy PubMed Central articles radiotherapy 2023 articles radiotherapy 2024 articles radiotherapy Scopus articles radiotherapy impact factor journals radiotherapy Scopus journals radiotherapy PubMed journals radiotherapy medical journals radiotherapy free journals radiotherapy best journals radiotherapy top journals radiotherapy free medical journals radiotherapy famous journals radiotherapy Google Scholar indexed journals chemotherapy articles chemotherapy Research articles chemotherapy review articles chemotherapy PubMed articles chemotherapy PubMed Central articles chemotherapy 2023 articles chemotherapy 2024 articles chemotherapy Scopus articles chemotherapy impact factor journals chemotherapy Scopus journals chemotherapy PubMed journals chemotherapy medical journals chemotherapy free journals chemotherapy best journals chemotherapy top journals chemotherapy free medical journals chemotherapy famous journals chemotherapy Google Scholar indexed journals rate of metastasis articles rate of metastasis Research articles rate of metastasis review articles rate of metastasis PubMed articles rate of metastasis PubMed Central articles rate of metastasis 2023 articles rate of metastasis 2024 articles rate of metastasis Scopus articles rate of metastasis impact factor journals rate of metastasis Scopus journals rate of metastasis PubMed journals rate of metastasis medical journals rate of metastasis free journals rate of metastasis best journals rate of metastasis top journals rate of metastasis free medical journals rate of metastasis famous journals rate of metastasis Google Scholar indexed journals prognostic factors articles prognostic factors Research articles prognostic factors review articles prognostic factors PubMed articles prognostic factors PubMed Central articles prognostic factors 2023 articles prognostic factors 2024 articles prognostic factors Scopus articles prognostic factors impact factor journals prognostic factors Scopus journals prognostic factors PubMed journals prognostic factors medical journals prognostic factors free journals prognostic factors best journals prognostic factors top journals prognostic factors free medical journals prognostic factors famous journals prognostic factors Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

1. Introduction

The most common cause of death in cancer patients continues to be lung cancer, with approximately 350 deaths per day by 2022 in the United States, which is greater than the deaths caused daily by breast, prostate, and pancreatic cancer combined [1]. Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for approximately 15% of lung cancer patients, and due to its increased incidence in women, the current male-to-female ratio is 1:1 [2,3]. In Colombia, lung cancer ranks sixth in frequency among malignancies reported annually and second in overall cancer mortality in both sexes, accounting for 11.8% of deaths [4]. In a case series that included 448 lung cancer patients managed at the Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INC) in Bogotá, approximately 8% corresponded to SCLC [5]. Additionally, SCLC is a special type of lung cancer that is characterized by a favorable initial response to chemotherapy and short-term radiation therapy, but it also tends to have a high rate of aggressive proliferation and a high rate of metastasis [3]; 70% of patients with SCLC are diagnosed with extended disease [6]. In addition to this factor, others have been considered poor prognostic factors, such as smoking history and low socioeconomic status, while good prognostic factors consist of Asian ethnicity and female gender [7]. There is limited information in Colombia on the clinical characteristics and survival of patients with SCLC. Therefore, this study aimed to describe the principal clinical features, survival outcomes, and prognostic factors of patients with SCLC treated at the INC between 2013 and 2018.

2. Methods

A retrospective analytical study was conducted, including patients with a confirmed diagnosis of SCLC, treated at the INC between January 2013 and December 2018. The exclusion criteria were patients under 18 years of age, patients with incomplete follow-up at the INC that did not allow collecting the necessary information to fill in the capturing tool, or with other uncontrolled synchronous tumors. Medical records were reviewed, and a data capturing form was created on the RedCap 7.1.2 © platform to record the information. Demographic, clinical, and clinicopathological stage variables, as well as therapeutic strategies, were analyzed. Data analysis was performed in R v4.1.1. Central tendency and dispersion measures were used for continuous variables according to data normality, and frequencies and percentages to describe the categorical variables. The 1989 classification of SCLC by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) as an extended or limited disease was used. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time elapsed between the pathology report’s date confirming SCLC and the date of death or the last day of follow-up at the INC.

Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank test to assess differences between subgroups. Statistically significant associations were considered at p<0.05. A Cox regression for multivariate analysis was performed to identify factors related to survival. The project was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the INC (N° CEI-00554-19), and data were reviewed by the institutional monitoring group.

3. Results

Between 2013 and 2018, a total of 35 patients with SCLC were included, with a median age of 61 years [Interquartile range (IQR)=54-71], 24 of which were men (68.6%); 1 patient had a controlled second primary prostate cancer, 23 patients (65.7%) were admitted with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score ≤2, and 5 (14.3%) had no smoking history. Of the patients included, 26 (74.3%) had extended, and 9 (25.7%) had limited disease (Table 1).

|

Characteristics n=35 |

n(%) |

|

Median age: 61 (IQR: 54-71) |

|

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

11(31.4) |

|

Male |

24(68.6) |

|

Oncological history |

|

|

Prostate |

1(2.8) |

|

No |

34(97.2) |

|

Smoking history |

|

|

Yes |

30(85.7) |

|

No |

5(14.3) |

|

ECOG |

|

|

0 |

1(2.8) |

|

1 |

12(34.3) |

|

2 |

10(28.6) |

|

3 |

7(20) |

|

4 |

5(14.3) |

|

Disease |

|

|

Extended |

26(74.3) |

|

Limited |

9(25.7) |

Table 1: Characteristics of patients included.

Abbreviations: IQR- Interquartile range; ECOG- Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

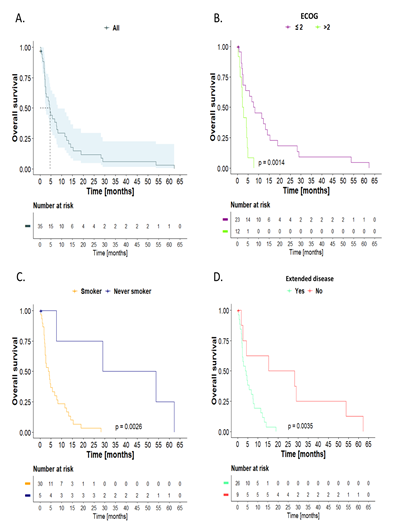

A total of 3 patients (8.6%) received initial extra-institutional surgical management. One of them had lobectomy with mediastinal nodal sampling; the surgery was R0, and the patient received cisplatin/etoposide and adjuvant radiotherapy, with a survival rate of 53.7 months. As for the other two patients, one underwent lobectomy, and the other had pulmonary wedge resection. Both had nodal sampling, but the surgeries had positive resection margins of lung parenchyma (R1). The median survival of these patients was 3 months. In addition, three patients in the limited disease group received definitive chemotherapy and radiotherapy; one of them also received prophylactic holocephalic radiotherapy. A total of 23 (65.7%) patients received best supportive care; of these patients, 47.8% had an ECOG = 3-4. Additionally, in the extended disease group, 6 (17.1%) remaining patients received palliative chemotherapy: 4 patients received cisplatin/etoposide, 1 patient carboplatin/etoposide, and another one received cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/etoposide. The latter regimen was administered in another institution. One of these patients received topotecan as second-line treatment, 2 of them received palliative holocephalic radiotherapy, and 5 patients also required stent placement in the superior vena cava. The median survival of the entire cohort was 4.5 months (95% CI, 2.56-8.28). Overall survival (OS) at 1 and 3 years was 26.5% and 5.9%, respectively (Figure 1A). The Kaplan-Meier curves showed that patients with an ECOG >2 (p<0.0014), smoking history (p=0.0026), and extended disease (p=0.0035) had a worse OS (Figure 1B-D). Table 2 summarizes median survival and 1- and 3-year survival rates according to ECOG, smoking history, and extended disease.

Figure 1: Overall survival, Kaplan-Meier curves: A) The entire cohort, stratified by: B) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG). C) Smoking history. D) Extended disease. Log-rank test comparison.

|

Characteristics |

Overall survival % [95% CI] |

Median survival (months) |

||

|

12 months |

36 months |

p-value |

||

|

ECOG |

||||

|

≤ 2 |

40.9 [24.8-67.6] |

9.09 [2.43-34.1] |

< 0.01 |

7.95 |

|

> 2 |

NE |

NE |

2.6 |

|

|

Smoking history |

||||

|

Smoker |

20.0 [9.78-40.9] |

NE |

< 0.01 |

4 |

|

Never smoker |

75.0 [42.6-100] |

50.0 [18.8-100] |

41.4 |

|

|

Extended disease |

||||

|

Yes |

15.4 [6.25-37.9] |

NE |

< 0.01 |

4 |

|

No |

62.5 [36.5-100] |

25.0 [7.53-83.0] |

21.8 |

|

Table 2: Medians of overall survival and survival at 1 and 3 years.

Abbreviations: CI- Confidence Interval; NE- Not Estimable.

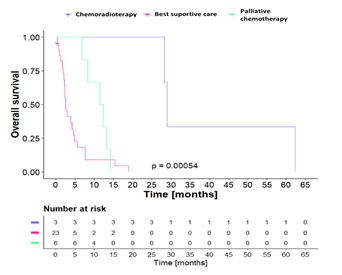

With respect to treatment, the median survival of patients who received chemotherapy, palliative chemotherapy, and best supportive care was 29.0, 11.9, and 2.6 months, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Overall survival according to treatment, Kaplan-Meier curves. Log-rank test comparison.

The Cox regression, including variables such as ECOG, smoking history, and extended disease, showed that the only independent variable for worse OS was ECOG >2 (HR: 2.59, 95% CI, 1.09-6.12, p=0.031) (Table 3).

|

Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||

|

Characteristics |

HR [ 95% CI] |

p-value |

HR [ 95% CI] |

p-value |

|

ECOG |

||||

|

≤ 2 |

Ref. |

<0.01 |

Ref. |

0.031 |

|

> 2 |

3.71 [1.57-8.74] |

2.70 [1.15-6.35] |

||

|

Smoking history |

||||

|

Smoker |

12.6 [1.65-96.2] |

0.015 |

7.35 [0.85-63.5] |

0.07 |

|

Never smoker |

Ref. |

Ref. |

||

|

Extended disease |

||||

|

Yes |

4.73 [1.55-14.5] |

<0.01 |

2.31 [0.73-7.25] |

0.2 |

|

No |

Ref. |

Ref. |

||

Table 3: Cox proportional hazards model.

Abbreviations: HR- Hazard Ratio; CI- Confidence Interval.

4. Discussion

This review evaluates the behavior of the classical variant of SCLC without including mixed-behavior tumors (non-small cell carcinomas with small cell components or large-cell tumors with neuroendocrine dedifferentiation). SCLC is the most aggressive form of lung cancer [8,9]; the reported 5-year OS is less than 10% [9], and not even screening programs with low-dose computed tomography have shown improvement in survival [10]. The OS of the entire study cohort at 1 and 3 years in our series was 26.5% and 5.9%, respectively, a finding that is consistent with the aggressive nature of this disease. Median survival intervals from the diagnosis of limited and extended diseases in multiple series are 15 to 20 months and 8 to 13 months, respectively. Approximately 20 to 40% of limited-stage patients and less than 5% of the extended-stage patients survive two years. These data do not include the possible impact of the introduction of first-line immunotherapy in extended disease on studies with atezolizumab or durvalumab [11-15]. This series represents a first approach to understanding the management of this pathology in Colombia and Latin America. The differences found regarding survival in our series are strongly related to the initial stage at the time of diagnosis of the patients, as well as to marked functional deterioration. Nevertheless, factors such as histopathological variants of the disease, considerations about tumor transcriptomics, opportunities for early access to treatment after diagnosis, and other barriers to accessing the health system were not analyzed. The SCLC classification that divides the disease into limited and extended was introduced in 1950 by the Veterans Administration Lung Study Group; later, in 1989, it was refined by the IASLC, and since 2007 this classification has been fully incorporated into the TNM system [8]. Despite this, in our series, we employed the limited and extended disease classification because it was the most common in the clinical histories of the patients included. Arriola et al. [16] described that 70% of 26,221 patients with SCLC in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database were diagnosed at stage IV; the median survival of these patients was 6 months (95% CI: 5.83-6.17), and 5-year survival was 1.6%. In our series, 74.3% of patients corresponded to extended disease, median survival was 4 months, 1-year survival was 15.4%, and 3-year survival was not estimable.

Due to the strong relationship between SCLC and smoking, it has been proposed that prevention of use or cessation of the habit may be the most effective strategy to reduce the impact of this disease on the general population [10]. However, assuring that this pathology only occurs in smoking patients is increasingly far from the reality since non-smoking patients with SCLC correspond to 2-3% in series from the United States and Spain [15,16] and 13-22% in series from Korea and China [17,18]. In our study, 14.3% of patients had no history of smoking. Additionally, these patients had a median OS of 41.4 months, clearly better than their smoking counterparts. These findings were similar to those described by Liu et al. [14], who reported that the median OS for patients with SCLC in non-smokers vs. smokers was 19.7 vs. 14.4 months (p=0.044), respectively; findings comparable to those reported by Torres-Duran et al. [12] in a series that included 32 patients with SCLC in never-smokers, where OS at 1 year was 34.4% and at 2 years, 21.9%. Varghese et al. [15] found that 17% of non-smoking patients with SCLC were patients who had a transformation to SCLC as a mechanism of resistance to the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in patients with mutated EGFR adenocarcinomas. In our series, none of the included patients presented this characteristic. The analysis of EGFR, ALK, and ROS-1 mutations in this population was not carried out; variables such as second-hand tobacco and radon exposure were also not analyzed. On the other hand, Belluomini et al. [20] described that special populations, such as elderly patients or patients with ECOG =2, have not been sufficiently studied in clinical trials to date. In our series, age was not associated with worse OS, but patients with ECOG>2 were, and although this association is expected, we consider that it is a factor that can contribute to decision-making in our daily clinical practice. Additionally, Arriola et al. [19], in the multivariate analysis of their SCLC series, found that women had a lower risk of death (HR=0.88, 95% CI: 0.86-0.90, p<0.0001) while patients ≥65 years were independently associated with lower OS (HR=1.43, 95% CI: 1.40-1.47, p<0.0001) [19]. These results were not found in our study, where 31.4% were women, and the median age was 61 years. In 2019, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) incorporated surgery as part of the multimodal treatment of SCLC, highlighting the role of surgery for early-stage disease [8]. According to the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines, surgery should be considered a treatment option in patients with clinical stages I and II (cT1-2N0) and in those cases with mixed SCLC and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) histology [9,21]. In our series, three patients with limited disease underwent surgical resection, but only one reached oncologic accuracy and completed multimodal management, obtaining a survival of 53.7 months. The median survival reported in the literature of surgically managed SCLC patients is approximately 20 months, and 5-year survival is between 11.1 and 52% [22]. Treatment with curative intent may be offered to patients with limited SCLC and consists of four cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy and concurrent radiation therapy, reporting median survival of approximately 27.2 months [23]. In our series, 8.6% of patients received definitive chemo-radiotherapy with curative intent, and the median survival was 29 months. On the other hand, the first line of treatment in metastatic SCLC is the combination of cisplatin or carboplatin and etoposide [23]. Patients who progress during treatment are known as platinum-resistant, those who progress within 90 days of treatment interruption are platinum-refractory, and those who progress after 90 days are known as platinum-sensitive [24]. In our series, patients who received palliative chemotherapy had a median survival of 11.9 months. It has recently been described that combining a PD-L1 inhibitor (durvalumab and atezolizumab) with etoposide-based chemotherapy may be an optimal first-line treatment option for patients with extended SCLC, improving OS [14,15]. Between 2013 and 2018, there were no data supporting the addition of these combinations to standard treatment, so none of the patients with SCLC managed at the INC had immunotherapy associated with their treatment. While the benefit of immunotherapy in extended disease appears to set a new direction in managing these patients, it is still unclear which subgroup may benefit the most in this regard. Gay et al. [25], using tumor expression and tumor transcriptomics data, have identified SCLC subtypes defined mainly by differential expression of transcription factors in three subtypes: ASCL1, NEUROD1, and POU2F3, or low expression of the three transcription factor signatures accompanied by an inflammatory genomic signature profile (SCLC-A, N, P, and I, respectively). They found that the SCLC-I profile receives the most benefit from adding immunotherapy to chemotherapy, while the other subtypes have distinct vulnerabilities, including poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors, Aurora kinase inhibitors, or BCL-2 [25]. In our series, tumor transcriptome analysis was not performed; however, a better understanding of the biology of this type of tumor may help better select patients who may respond more efficiently to immunotherapy or other types of interventions. In our series, only one patient received prophylactic central nervous system radiotherapy, although the benefit of this intervention appears to be more consistent in limited-disease patients who have responded to or maintained stable disease after treatment with systemic chemotherapies [26,27]. It is necessary to establish the behavior of the disease in the central nervous system and the impact of these interventions in terms of progression-free survival, OS, and neurocognitive impairment. The limitations of this study are related to the fact that it is retrospective, it was carried out in a single oncologic center with a small sample of patients, and there was difficulty in the complete collection of all clinical variables. Nevertheless, it is the first study in Colombia to describe the clinical characteristics and survival of patients with SCLC.

5. Conclusions

SCLC has the worst prognosis among all types of lung cancer worldwide. In Colombia, the findings are no different, and additionally, as found in this study, survival was clearly affected in patients with ECOG>2, smoking history, and extended disease. It leads us to think that it is essential to improve access routes for diagnosis and management in specialized oncology centers and to promote the prevention of tobacco use and smoking cessation in the country.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 72 (2022): 7-33.

- Ganti AKP, Loo BW, Bassetti M, et al. Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 19 (2021): 1441-1464.

- Wang Y, Zou S, Zhao Z, et al. New insights into small-cell lung cancer development and therapy. Cell Biol Int 44 (2020): 1564-1576.

- Cardona AF, Mejía SA, Viola L, et al. Lung Cancer in Colombia. J Thorac Oncol 17 (2022): 953-960.

- Alarcón ML, Brugés R, Carvajal C, et al. Characteristics of patients with non-small cell lung cancer at the National Cancer Institute of Bogotá. Revista Colombiana de Cancerología 25 (2021).

- Zhou T, Zhang Z, Luo F, et al. Comparison of First-Line Treatments for Patients With Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 3 (2020): e2015748.

- Ou SH, Ziogas A, Zell JA. Prognostic factors for survival in extensive stage small cell lung cancer (ED-SCLC): the importance of smoking history, socioeconomic and marital statuses, and ethnicity. J Thorac Oncol 4 (2009): 37-43.

- Loizidou A, Lim E. Is Small Cell Lung Cancer a Surgical Disease at the Present Time? Thorac Surg Clin 31 (2021): 317-321.

- Dingemans AC, Früh M, Ardizzoni A, et al. Small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up?. Ann Oncol 32 (2021): 839-853.

- Silva M, Galeone C, Sverzellati N, et al. Screening with Low-Dose Computed Tomography Does Not Improve Survival of Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 11 (2016): 187-193.

- Seifter EJ, Ihde DC. Therapy of small cell lung cancer: a perspective on two decades of clinical research. Semin Oncol 15 (1988): 278-299.

- Osterlind K, Hansen HH, Hansen M, et al. Long-term disease-free survival in small-cell carcinoma of the lung: a study of clinical determinants. J Clin Oncol 4 (1986): 1307-1313.

- Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, et al. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 394 (2019): 1929-1939.

- West H, McCleod M, Hussein M, et al. Atezolizumab combination in with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment for metastatic non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower130): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 20 (2019): 924-937.

- Varghese AM, Zakowski MF, Yu HA, et al. Small-cell lung cancers in patients who never smoked cigarettes. J Thorac Oncol 9 (2014): 892-896.

- Torres-Durán M, Curiel-García MT, Ruano-Ravina A, et al. Small-cell lung cancer in never-smokers. ESMO Open 6 (2021): 100059.

- Sun JM, Choi YL, Ji JH, et al. Small-cell lung cancer detection in never-smokers: clinical characteristics and multigene mutation profiling using targeted next-generation sequencing. Ann Oncol 26 (2015): 161-166.

- Liu X, Jiang T, Li W, et al. Characterization of never-smoking and its association with clinical outcomes in Chinese patients with small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 115 (2018): 109-115.

- Arriola E, Trigo JM, Sánchez-Gastaldo A, et al. Prognostic Value of Clinical Staging According to TNM in Patients with SCLC: A Real-World Surveillance Epidemiology and End-Results Database Analysis. JTO Clin Res Rep 3 (2021): 100266.

- Belluomini L, Calvetti L, Inno A, et al. SCLC Treatment in the Immuno-Oncology Era: Current Evidence and Unmet Needs. Front Oncol 12 (2022): 840783.

- Petrella F, Bardoni C, Casiraghi M, et al. The Role of Surgery in High-Grade Neuroendocrine Cancer: Indications for Clinical Practice. Front Med (Lausanne) 9 (2022): 869320.

- Hiddinga BI, Raskin J, Janssens A, et al. Recent developments in the treatment of small cell lung cancer. Eur Respir Rev 30 (2021): 210079.

- Ardizzoni A, Tiseo M, Boni L. Validation of standard definition of sensitive versus refractory relapsed small cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of topotecan second-line trials. Eur J Cancer 50 (2014): 2211-2218.

- Zhou T, Zhang Z, Luo F, et al. Comparison of First-Line Treatments for Patients With Extensive-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 3 (2020): e2015748.

- Gay CM, Stewart CA, Park EM, et al. Patterns of transcription factor programs and immune pathway activation define four major subtypes of SCLC with distinct therapeutic vulnerabilities. Cancer Cell 39 (2021): 346-360.e7.

- Aupérin A, Arriagada R, Pignon JP, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with small-cell lung cancer in complete remission. Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation Overview Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med 341 (1999): 476-484.

- Meert AP, Paesmans M, Berghmans T, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation in small cell lung cancer: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 1 (2001): 5.