Safety and Efficacy of Tenecteplase among Patients with ST Elevated Myocardial Infarction - Experience in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Bangladesh

Article Information

Md. Mahidur Rahman1*, Syeda Mehbuba Joty2, Tanvir Jeshan3, Tamal Peter Ghosh4, Moeen Uddin Ahmed5, Solaiman Hossain6, KM Shaiful Islam7, Noshin Saiyara8, Faridul Islam9

1Junior Consultant, Department of Cardiology, Enam Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2Resident, Department of General Surgery, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3Registrar, Department of Cardiology, Enam Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4Medical Officer, National Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases, Dhaka, Bangladesh

5Professor & Head, Department of Cardiology, Enam Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

6Professor, Department of Cardiology, Enam Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

7Assistant Professor, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

8ST3, General Surgery, East Midlands, UK

9Registrar, Department of Urology, Royal Derby Hospital NHS Trust, UK

*Corresponding author: Md. Mahidur Rahman, Junior Consultant, Department of Cardiology, Enam Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Received: 08 November 2023; Accepted: 14 November 2023; Published: 20 November 2023

Citation: Md. Mahidur Rahman, Syeda Mehbuba Joty, Tanvir Jeshan, Tamal Peter Ghosh, Solaiman Hossain, Moeen Uddin Ahmed, KM Shaiful Islam, Noshin Saiyara, Faridul Islam. Safety and efficacy of Tenecteplase among patients with ST elevated Myocardial Infarction - Experience in a tertiary care hospital in Bangladesh. Cardiology and Cardiovascular Medicine. 7 (2023): 343-348.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Introduction: The re-establishment of the blood flow to closed vessels as quickly as possible (reperfusion), is the standard treatment for ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI), with the aim of preventing myocardial necrosis and preserving myocardial muscle mass in order to lower the risk of heart failure and ultimately increase the patient's survival.

Aim of the study: To evaluate the safety and efficacy of Tenecteplase (TNK-tPA) among STEMI patients.

Methodology & Materials: This was an observational study and was conducted in the Department of Cardiology, Enam Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh during the period from 1 July 2022 to 30 June 2023. In our study, we took 50 patients diagnosed with either ST elevated Myocardial Infarction or new onset LBBB in ECG.

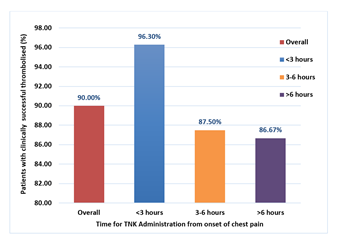

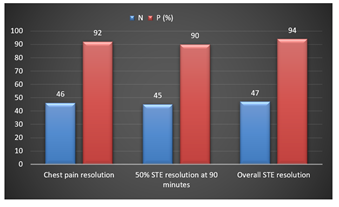

Result: Among the study population, duration of chest pain was 5.21 ± 3.05 hours. We found the overall rate of clinically successful thrombolysis (CST) with TNK was 90.0%. Patients who got TNK within 03 hours had CST rate of 96.30% compared to patients who got delayed TNK treatment (86.67% CST, >6 hours from onset of pain). Chest pain resolution was found in 92% patients following pharmacological fibrinolysis with TNK. About 90% of patients had at least 50% resolution of ST elevated segments at 90 minutes. About 10% had hemoptysis, 6% had gum bleeding & arrhythmia, and only 1(2%) had fatal intra-cerebral haemorrhage (ICH) who eventually died.

Conclusion: Our findings indicate that reperfusion therapy with TNK-tPA is the best fibrinolytic treatment option for STEMI patients with relatively few side-effects profile.

Keywords

Myocardial infarction; STEMI; Thrombolysis; Tenecteplase; Efficacy

Myocardial infarction articles; STEMI articles; Thrombolysis articles; Tenecteplase articles; Efficacy articles

Article Details

Introduction

The leading cause of death in the majority of nations is cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, it places a heavy financial load on healthcare systems and results in complications, substantial disability, and productivity loss. [1,2] One in every three deaths in Western countries is brought on by coronary artery disease (CAD), which annually accounts for about 7 million fatalities worldwide. [3] The usual course of action for ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) involves the prompt restoration of blood flow to closed vessels (re-perfusion), which aims to halt myocardial necrosis and preserve myocardial muscle mass in order to lower the risk of heart failure and ultimately increase the patient's survival. Acute coronary syndromes are difficult to treat, but STEMI is the most difficult. [4] An electrocardiographic ST elevation (or new onset LBBB) and the following release of myocardial necrotic biomarkers characterize STEMI, a clinical condition that exhibits the classic signs of myocardial ischemia. Acute myocardial injury with clinical evidence of acute myocardial ischemia, detection of rise and/or fall in cardiac Troponin (cTn) values with at least one value above the 99th percentile URL, and at least one of the following: symptoms of myocardial ischemia, new ischemic ECG changes, is the definition of myocardial infarction used by the European Society of Cardiology, American College of Cardiology Foundation, and American Heart Association (AHA) [5]. The in-hospital mortality of STEMI ranges from 6% to 14% and has decreased over time in tandem with re-perfusion strategy advancement. Angioplasty and fibrinolysis are two techniques used to perform re-perfusion. The two types of thrombolytic agents targeting fibrin are known as fibrin-specific and fibrin-nonspecific. [6] Although thrombolytic therapy reduces mortality, there is a higher risk of complications involving bleeding. Major bleeding occurs within 10% of patients getting thrombolytic therapy, and cerebral hemorrhage affects 1% of patients. [6,7] The danger of adverse outcomes makes doctors hesitant to use thrombolytic therapy, which may result in underutilization of this potentially life-saving medicine [8]. In 50–60% of STEMI patients, plasminogen activators return the heart's normal blood flow.[9] Patients have a higher probability of living longer when fibrinolytic medications are used successfully. The commencement of the disease's symptoms and the prescription of the drug, however, play a crucial role in how well these elements work. Additionally, when there has been a delay of 30 minutes or less between the start of clinical symptoms and the injection, these elements will have the greatest effect. [9] The two most often utilized plasminogen activators for treating acute myocardial infarction are alteplase and teneplase (TNK) [3,10]. Tenecteplase was developed to improve the capabilities of t-PA and was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The results of clinical trials for AMI led to improved TNK-tPA dosing recommendations. Weight-optimized TNK-tPA dosage really resulted in safer and more effective outcomes. According to a study of the TNK-tPA clinical studies and comparisons of this medication to other thrombolytics, TNK-tPA is efficient and exhibits a broad therapeutic margin of safety, especially in regard to vulnerable categories like low-body-weight women and older people [11].

Objective of the study

The main objective of the study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of Tenecteplase (TNK-tPA) among STEMI patients.

Methodology and Materials

This was an observational study and was conducted in the Department of Cardiology, Enam Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh during the period from 1 July 2022 to 30 June 2023. In our study, we took 50 patients diagnosed with ST elevated Myocardial Infarction or new onset LBBB in ECG. These are the following criteria to be eligible for enrollment as our study participants: a) Patients aged between 30 to 75 years; b)Patients with pain onset duration ≤ 180 minutes; c) Patients with weight-adjusted Tenecteplase bolus; d) Patients with adjunctive therapy- LMWH & Dual anti-platelet therapy (DAPT); e) Patients who stayed in the hospital for at least 72 hours were included in the study; And a) Patients with any contra-indication to Tenecteplase; b) Patients with previous Coronary artery bypass (CABG) surgery; c) Patients who were not willing to participate; d) Patients with known allergy to study drugs were excluded from our study.

According to standard clinical practice, tenecteplase was given to STEMI patients who presented to the centers in a weight-adjusted dose pattern at the treating cardiologist's or medical professional's discretion. [12] The dose of TNK-tPA was based on a patient’s weight. The bolus and initial infusions of heparin were specified in the trial protocols. Patients received low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) with 30 mg IV bolus after 15 minutes of Tenecteplase followed by 1 mg/kg body weight every 12 hours until discharge.

Statistical Analysis

All data were captured methodically on premade data-collecting forms. Quantitative data were expressed as mean and standard deviation and qualitative data as frequency distribution & percentage. SPSS 22 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) was used for the statistical analysis. A probability value of 0.05 or less was regarded as significant. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Enam Medical College Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Results

|

Baseline Characteristics |

N=50 |

P(%) |

|

Age (years) |

53.85±11.39 |

|

|

Hypertension |

42 |

84 |

|

Smoking |

28 |

56 |

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

33 |

66 |

|

Dyslipidemia |

18 |

36 |

|

History of IHD |

14 |

28 |

|

Location of MI |

||

|

Inferior |

26 |

52 |

|

Anterior |

16 |

32 |

|

Posterior |

8 |

16 |

|

Killip class |

||

|

I |

22 |

44 |

|

II |

13 |

26 |

|

III |

10 |

20 |

|

IV |

7 |

14 |

|

Heart Rate (per minute) |

86 ± 17 |

|

|

Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) |

135.24 ± 20.78 |

|

|

Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) |

83.94 ± 10.69 |

|

|

Triglycerides (mg/dL) |

289.35±42.04 |

|

|

Total cholesterol (mg/dL) |

199.83 ± 42.16 |

|

|

HDL (mg/dL) |

40.21 ± 9.05 |

|

|

LDL (mg/dL) |

152.35 ± 35.59 |

|

|

Chest pain duration (hours) |

5.21 ± 3.05 |

|

|

HDL=high-density lipoprotein, LDL=low-density lipoprotein |

||

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of our study subjects.

|

Concomitant medications |

N |

P(%) |

|

Aspirin + Clopidogrel |

48 |

96 |

|

LMWH |

45 |

90 |

|

Beta-blockers |

34 |

68 |

|

GTN |

39 |

78 |

|

LMWH= low molecular weight heparin; GTN= glyceryl trinitrate |

||

Table 2: Distribution of our study patients by concomitant medication

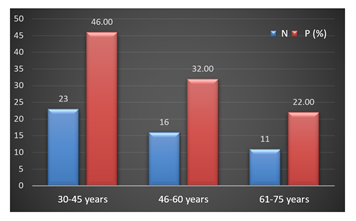

Majority (46%) of our patients were aged 30-45 years, followed by 32% & 22% of patients aged 46-60 & 61-75 years old respectively [Figure 1].

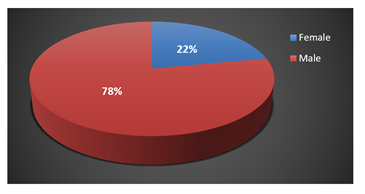

Most of our study patients were male (78%) compared to female (22%). The male & female ratio was found 3.54:1 in the study [Figure 2].

We found the age was 53.85±11.39 years. The majority of patients had hypertension (84%) followed by Diabetes Mellitus (66%) & dyslipidemia (36%). Among all patients 56% were smokers. Most of our patients had inferior (52%) locations of MI, followed by anterior (32%) & posterior (16%). On presentation, of all our subjects 44% were Killip class I, 26% were Killip II, 20% & 14% were Killip III & IV respectively. The duration of chest pain was 5.21 ± 3.05 hours [Table 1].

Among all our study subjects, 96% received both clopidogrel and aspirin together, while 90% received LMWH. Beta-blockers and glyceryl trinitrate were administered in 68% and 78% of patients respectively [Table 2].

|

Complications |

N |

P(%) |

|

Hemoptysis |

5 |

10 |

|

Gum bleeding |

3 |

6 |

|

Epistaxis |

2 |

4 |

|

Arrhythmia |

3 |

6 |

|

Shock |

2 |

4 |

|

Intracerebral hemorrhage |

1 |

2 |

Table 3: Distribution of our study patients by complications of Tenecteplase

We found the overall rate of clinically successful thrombolysis (CST) with TNK was 90.0% in our study. Delayed tenecteplase treatment (>6 hours from the onset of chest pain) resulted in a reduced success rate (86.67%) compared to patients who got tenecteplase within 3 hours of symptoms & between 3 to 6 hours (96.30% & 87.50%, respectively) [Figure 3].

After pharmacological fibrinolysis with TNK, chest pain resolution was found in 92% of patients and the time to resolution of chest pain was 53.21 ± 9.42 minutes. About 90% of patients had 50% resolution of STE at 90 minutes and the mean time for 50% STE resolution was 73.18 ± 4.74 minutes. About 94% of patients had overall STE resolution [Figure 4].

Among all patients, majority (10%) patients had hemoptysis, followed by 6% had gum bleeding & arrhythmia, 4% had epistaxis & shock, and only 1(2%) patient died due to fatal intra-cerebral hemorrhage (ICH) [Table 3].

Discussion

In our study majority (46%) of our patients were aged 30-45 years, the age distribution lies in our study subjects was between 30 to 75 years. While in a study done by Neela at al. found the age distribution in their study was between 21 and 80 years [13]. The majority of our study patients were male (78%). Neela et al. & Curtis et al. recorded the majority of patients in their study were male. [13,14] The male & female ratio was found 3.54:1 in the study while Iyengar et al. found 4.88: 1 in their study [15]. We found the mean age was 53.85±11.39 years. Neela et al. found the mean age of TNK-tPA group was 50.34±12.10 years, followed by Iyengar et al. found the mean age 55.80±10.34 years while Curtis et al. found the mean age in Tenecteplase group was 61 years [13-15]. The majority of patients had hypertension (84%) followed by DM (66%) & dyslipidemia (36%). Curtis et al. found about 16% & 38% had DM & hypertension respectively while Iyengar et al. found hypertension (76.71%) and diabetes (47.97%) in their study. [14,15] Among all our patients 56% were smokers, but there were 45% & 40.82% current smokers in other studies [14,15]. Most of our patients had inferior (52%) locations of MI, while both Iyengar et al. & Curtis et al. found majority of patients with anterior location 55.01% & 40% respectively. [14,15] Of all our subjects, the majority of patients were Killip class I. Our findings were similar to other studies [14,15]. We found the overall rate of clinically successful thrombolysis (CST) with TNK was 90.0%. Similar findings were made in the "Indian Registry" and by Iyengar et al., who found that tenecteplase was effective in treating more than 90% of CST cases, including those in high-risk subgroups such the elderly, diabetics, hypertensives, smokers, and dyslipidemic patients. [15,16] The fact successfully draws attention to the satisfactory clinical effectiveness of native TNK in standard clinical practice. Previous investigations have shown that 10% to 25% of patients with acute myocardial infarction have diabetes mellitus. [17] This prevalence was substantially greater (66%) in the current investigation. In a research done by Sathyamurthy et al., the inclusion rate of diabetic individuals was stated as being similarly high (44.94%) [18].

In this study, 90% patients had 50% resolution of elevated ST segments at 90 minutes. In a research work, the incidence of resolution of 50% ST-elevation and resolution of symptoms was reported in 98% of patients. [13] In contrast to Singh et al.'s earlier investigation, these findings were incongruous. The incidence of negative events was 5.3%, while 90.5% and 95.4% of patients, respectively, reported that their 50% ST elevation and chest discomfort had resolved. [19] In 2017, Iyengar et al. carried out a multicentric observational analysis of STEMI patients. After pharmacological fibrinolysis with TNK tPA, 93.2% of the participants in their trial reported relief from chest discomfort. [15] After pharmacological fibrinolysis with TNK, 92% of all of our patients reported relief from chest discomfort. Bleeding is the main adverse effect of thrombolytics. In a research done by Neera et al., 4% of participants in the TNK tPA group had bleeding. [13] It did not agree with a prior study conducted by Yazdi et al. In their 142-patient research, 28.4% of those receiving TNK tPA had bleeding. [20] Iyengar et al. conducted a post-licensure, observational, and prescription event monitoring study in 2009 with 2100 STEMI patients. 4.62% of the TNK tPA participants in their research suffered bleeding. [21] It agreed with the findings of our study, which showed that 6% of patients experienced bleeding and arrhythmia. In our study, the mortality rate was 2%. Compared to the Kerala ACS registry (8.2%), the in-hospital mortality rate was lower (0.69%). [22] Given the similarity in the use of antiplatelet, heparin, beta-blocker, and statin medications across all studies, it is likely that patient characteristics and early reperfusion are the primary determinants of outcomes rather than management variations. Since the mortality rate is a registry of prescription event monitoring observational studies, it is probably underreported. Mortality rates of 4.3% were reported by Danchin N et al. (3.3% for patients getting thrombolysis prehospital and 6.1% for patients receiving thrombolysis in-hospital). In contrast, patients who did not receive reperfusion had an in-hospital death rate of 9.5%. [23] Comparatively speaking, fatality rates in our study were lower (0.69%). The overall mortality is lower than previously reported incidences of up to 6.5% in the TIMI 10B trial and 6.18% in the ASSENT-2 study. [17] The Indian registry recorded an overall death rate of 1.69%, with patients receiving delayed treatment seeing a mortality rise of more than three times that rate [16]. This study has several limitations. It was a single-centre study. The sample size was not rich and study period was short. After evaluating those patients, we did not follow them up for a long term and have not known other possible interference that may happen in the long term with these patients. Due to different types of short-comings, post-thrombolytic coronary angiogram (CAG) was not possible, hence angiographic findings could not be included in our study.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In our study, Pharmacological reperfusion therapy with TNK-tPA was found to be a highly effective thrombolytic treatment for STEMI. Particularly, in a country like Bangladesh where the scarcity of established PCI centres necessitates an effective thrombolytic therapy for STEMI patients. Our findings also support tenecteplase's efficacy and safety in individuals with co-morbidities such as hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia. Tenecteplase could also be the best option for buy some time for performing pharmaco-invasive therapy. Our findings indicate that reperfusion therapy with TNK-tPA is the best thrombolytic treatment option for STEMI patients. So, we recommend that further study with a prospective and longitudinal study design including larger sample size needs to be done to support ongoing research into TNK-tPA and make it accessible in all emergency scenarios.

References

- Tullmann DF, Haugh KH, Dracup KA, et al. A randomized controlled trial to reduce delay in older adults seeking help for symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Res Nurs Health 30 (2007): 485-497.

- Prabhakaran D, Jeemon P, Sharma M, et al. The changing patterns of cardiovascular diseases and their risk factors in the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2016. Lancet Glob Health 6 (2018): e1339-e51.

- Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 33 (2012): 2569-2619.

- Guha S, Sethi R, Ray S, et al. Cardiological Society of India: Position statement for the management of ST elevation myocardial infarction in India. Indian Heart J 69 Suppl 1 (2017): S63-S97.

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur Heart J 40 (2019): 237-269.

- Guillermin A, Yan DJ, Perrier A, et al. Safety and efficacy of tenecteplase versus alteplase in acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arch Med Sci 12 (2016): 1181-1187.

- Marti C, John G, Konstantinides S, et al. Systemic thrombolytic therapy for acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 36 (2015): 605-614.

- Stein PD, Matta F. Thrombolytic therapy in unstable patients with acute pulmonary embolism: saves lives but underused. Am J Med 125 (2012): 465-470.

- Tourani S, Bashzar S, Nikfar S, et al. Effectiveness of tenecteplase versus streptokinase in treatment of acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Tehran Univ Med J 76 (2018): 380-387.

- Konstantinides S, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Kardiol Pol 72 (2014): 997-1053.

- Gibson CM, Marble SJ. Issues in the assessment of the safety and efficacy of tenecteplase (TNK-tPA). Clinical cardiology 24 (2001): 577-584.

- ASSENT-2 Investigators. Single-bolus tenecteplase compared with frontloaded alteplase in acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 354 (1999): 716-722.

- Neela B, Gunreddy VR, Chandupatla MR, et al. Safety and efficacy of streptokinase, tenecteplase, and reteplase in patients diagnosed with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a comparative study. Journal of Indian College of Cardiology 10 (2020): 134-138.

- Curtis JP, Alexander JH, Huang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of two unfractionated heparin dosing strategies with tenecteplase in acute myocardial infarction (results from Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic Regimens 2 and 3). The American journal of cardiology 94 (2004): 279-283.

- Iyengar SS, Nair T, Hiremath J, et al. Pharmacological reperfusion therapy with tenecteplase in 7,668 Indian patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction - A real world Indian experience. J Assoc Physicians India 65 (2017).

- Iyengar SS, Nair T, Hiremath JS, et al. Pharmacologic reperfusion therapy with indigenous tenecteplase in 15,222 patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction – the Indian registry. Indian Heart J 65 (2013): 436-441.

- Cannon CP, Gibson CM, McCabe CH, et al. TNK-tissue plasminogen activator compared with front-loaded alteplase in acute myocardial infarction: results of the TIMI 10B trial. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 10B Investigators. Circulation 98 (1998): 2805-2814.

- Sathyamurthy I, Jayanthi K, Iyengar SS, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenecteplase in diabetic and non-diabetic patients of STEMI - Indian registry data. J Assoc Physicians India 58 (2010).

- Singh RK, Trailokya A, Naik MM. Post-reteplase evaluation of clinical safety & Efficacy in Indian patients (precise in study). J Assoc Physicians India 63 (2015): 30.

- Yazdi AH, Khalilipur E, Zahedmehr A, et al. Fibrinolytic Therapy With Streptokinase vs Tenecteplase for Patients With ST Elevation MI Not Amenable to Primary PCI. Iranian Heart Journal 18 (2017): 43-49.

- Iyengar SS, Nair T, Sathyamurthy I, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenecteplase in ST elevation myocardial infarction patients from the Elaxim Indian Registry. Indian Heart J 61 (2009).

- Mohanan PP, Mathew R, Harikrishnan S, et al. Presentation, management, and outcomes of 25 748 acute coronary syndrome admissions in Kerala, India: results from the Kerala ACS Registry. Eur Heart J 34 (2013): 121-129.

- Danchin N, Coste P, Ferrières J, et al. Comparison of thrombolysis followed by broad use of percutaneous coronary intervention with primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment–elevation acute myocardial infarction: Data from the French registry on acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (FAST-MI). Circulation 118 (2008): 268-276.