Psychological and Physiological Effects in Satoyama Activities of Older Adult Volunteers in the Urban Green Space in Spring and Autumn

Article Information

Qiongying Xiang*1, Zhengwei Yuan1, Yingming Mao1

1Graduate School of Horticulture, Chiba University;

*Corresponding Author: Qiongying Xiang. Graduate School of Horticulture, Chiba University

Received: 09 May 2023; Accepted: 16 May 2023; Published: 12 July 2023

Citation:

Qiongying Xiang, Zhengwei Yuan and Yingming Mao. Psychological and Physiological Effects in Satoyama Activities of Older Adult Volunteers in the Urban Green Space in Spring and Autumn. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Disorders. 7 (2023): 60-79.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

In the context of high urbanization, developed countries are facing the social phenomenon of severe aging. In Japan, several studies have highlighted the subjective significance of Satoyama activities for volunteers in terms of gaining a sense of meaning and mental health recovery in Satoyama. However, there is a lack of studies investigating the impact of Satoyama activities on both physical and mental health, particularly under different seasons. Therefore, this study aims to explore the physiological and psychological restorative effects of forest therapy on older adult volunteers (n=12) in Satoyama, using young students (n=12) in the city as a control group. Participants engaged in Satoyama activities, including a ten-minute "Nature Observation" walk through the forest and a thirty-minute "Satoyama Work" after arriving at the Satoyama site. The blood pressure and heart rate indicators of participants were collected as physiological data, while the Profile of Mood States 2nd edition and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory scales were used as psychological data. Landscape Image Sketch technology and text mining were utilized to analyze the participants' impressions of Satoyama. Our results indicate that the physical recovery of older adult volunteers was better in spring than in autumn, while the psychological recovery was more prominent in autumn than in spring. The peaceful mood and construction of Satoyama by older adult volunteers were observed in the Landscape Image Sketch Technique of Satoyama. In conclusion, this study sheds light on the potential of Satoyama to promote physical and mental health among older adult volunteers, with the consideration of seasonal variations being an essential aspect.

Keywords

Satoyama activities, Forest therapy; Landscape Image Sketching Technique; Profile of mood states; State- trait anxiety inventory

Satoyama activities articles; Forest therapy articles; Landscape Image Sketching Technique articles; Profile of mood states articles; State- trait anxiety inventory articles

Satoyama activities articles Satoyama activities Research articles Satoyama activities review articles Satoyama activities PubMed articles Satoyama activities PubMed Central articles Satoyama activities 2023 articles Satoyama activities 2024 articles Satoyama activities Scopus articles Satoyama activities impact factor journals Satoyama activities Scopus journals Satoyama activities PubMed journals Satoyama activities medical journals Satoyama activities free journals Satoyama activities best journals Satoyama activities top journals Satoyama activities free medical journals Satoyama activities famous journals Satoyama activities Google Scholar indexed journals Forest therapy articles Forest therapy Research articles Forest therapy review articles Forest therapy PubMed articles Forest therapy PubMed Central articles Forest therapy 2023 articles Forest therapy 2024 articles Forest therapy Scopus articles Forest therapy impact factor journals Forest therapy Scopus journals Forest therapy PubMed journals Forest therapy medical journals Forest therapy free journals Forest therapy best journals Forest therapy top journals Forest therapy free medical journals Forest therapy famous journals Forest therapy Google Scholar indexed journals Landscape Image Sketching Technique articles Landscape Image Sketching Technique Research articles Landscape Image Sketching Technique review articles Landscape Image Sketching Technique PubMed articles Landscape Image Sketching Technique PubMed Central articles Landscape Image Sketching Technique 2023 articles Landscape Image Sketching Technique 2024 articles Landscape Image Sketching Technique Scopus articles Landscape Image Sketching Technique impact factor journals Landscape Image Sketching Technique Scopus journals Landscape Image Sketching Technique PubMed journals Landscape Image Sketching Technique medical journals Landscape Image Sketching Technique free journals Landscape Image Sketching Technique best journals Landscape Image Sketching Technique top journals Landscape Image Sketching Technique free medical journals Landscape Image Sketching Technique famous journals Landscape Image Sketching Technique Google Scholar indexed journals Profile of mood states articles Profile of mood states Research articles Profile of mood states review articles Profile of mood states PubMed articles Profile of mood states PubMed Central articles Profile of mood states 2023 articles Profile of mood states 2024 articles Profile of mood states Scopus articles Profile of mood states impact factor journals Profile of mood states Scopus journals Profile of mood states PubMed journals Profile of mood states medical journals Profile of mood states free journals Profile of mood states best journals Profile of mood states top journals Profile of mood states free medical journals Profile of mood states famous journals Profile of mood states Google Scholar indexed journals State- trait anxiety inventory articles State- trait anxiety inventory Research articles State- trait anxiety inventory review articles State- trait anxiety inventory PubMed articles State- trait anxiety inventory PubMed Central articles State- trait anxiety inventory 2023 articles State- trait anxiety inventory 2024 articles State- trait anxiety inventory Scopus articles State- trait anxiety inventory impact factor journals State- trait anxiety inventory Scopus journals State- trait anxiety inventory PubMed journals State- trait anxiety inventory medical journals State- trait anxiety inventory free journals State- trait anxiety inventory best journals State- trait anxiety inventory top journals State- trait anxiety inventory free medical journals State- trait anxiety inventory famous journals State- trait anxiety inventory Google Scholar indexed journals forest bathing articles forest bathing Research articles forest bathing review articles forest bathing PubMed articles forest bathing PubMed Central articles forest bathing 2023 articles forest bathing 2024 articles forest bathing Scopus articles forest bathing impact factor journals forest bathing Scopus journals forest bathing PubMed journals forest bathing medical journals forest bathing free journals forest bathing best journals forest bathing top journals forest bathing free medical journals forest bathing famous journals forest bathing Google Scholar indexed journals physiological articles physiological Research articles physiological review articles physiological PubMed articles physiological PubMed Central articles physiological 2023 articles physiological 2024 articles physiological Scopus articles physiological impact factor journals physiological Scopus journals physiological PubMed journals physiological medical journals physiological free journals physiological best journals physiological top journals physiological free medical journals physiological famous journals physiological Google Scholar indexed journals thermometers articles thermometers Research articles thermometers review articles thermometers PubMed articles thermometers PubMed Central articles thermometers 2023 articles thermometers 2024 articles thermometers Scopus articles thermometers impact factor journals thermometers Scopus journals thermometers PubMed journals thermometers medical journals thermometers free journals thermometers best journals thermometers top journals thermometers free medical journals thermometers famous journals thermometers Google Scholar indexed journals depression-dejection articles depression-dejection Research articles depression-dejection review articles depression-dejection PubMed articles depression-dejection PubMed Central articles depression-dejection 2023 articles depression-dejection 2024 articles depression-dejection Scopus articles depression-dejection impact factor journals depression-dejection Scopus journals depression-dejection PubMed journals depression-dejection medical journals depression-dejection free journals depression-dejection best journals depression-dejection top journals depression-dejection free medical journals depression-dejection famous journals depression-dejection Google Scholar indexed journals State-Trait Anxiety Inventory articles State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Research articles State-Trait Anxiety Inventory review articles State-Trait Anxiety Inventory PubMed articles State-Trait Anxiety Inventory PubMed Central articles State-Trait Anxiety Inventory 2023 articles State-Trait Anxiety Inventory 2024 articles State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Scopus articles State-Trait Anxiety Inventory impact factor journals State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Scopus journals State-Trait Anxiety Inventory PubMed journals State-Trait Anxiety Inventory medical journals State-Trait Anxiety Inventory free journals State-Trait Anxiety Inventory best journals State-Trait Anxiety Inventory top journals State-Trait Anxiety Inventory free medical journals State-Trait Anxiety Inventory famous journals State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

1. Introduction

1.1 Aging society and older adult volunteers

The median age of the world population increased in the second half of the twentieth century as fertility declined and the average life expectancy increased by 20 years. These factors, combined with rising fertility in many countries during the two decades after World War II (i.e., the –baby booml), led to an increase in the number of people aged ≥65 in the 2010 – 2030 period [1]. Epidemiological studies have shown that 11% of the world_s population is over 60 years old, and this number is expected to increase to 22% by 2050 [2]. In developed countries, the number of adults over the age of 65 is increasing. Indicators from the Centers for Disease Control_s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report show that over a 30-year period, the population aged 65 and older has doubled. From 2000 to 2030, the proportion of people aged 65 and older will increase from 12.4% to 19.6% in the United States, from 12.6% to 20.3% in Europe, and from 6% to 12% in Asia [1, 3]. Japan is the world_s most aging country, with 27.1% of the population over 65 years old in 2017 [4].

Gerontologists tend to use chronological age to divide old age into three subcategories: the oldest-old or people aged 85 years or older, people aged 75–84 years, and people aged 65–74 years [5]. Older adults have decreased metabolism, weakened immune systems, and aging cells and face an epidemiologic shift in which chronic diseases increase their chances of becoming disabled [6,7]. In the United States, approximately 80% of people aged ≥ 65 years have at least one chronic disease, and 50% have at least two. Diabetes leads to excess morbidity and increased health care costs, affecting approximately one in five (18.7%) people aged ≥ 65 years, and the impact of diabetes will increase as the population ages [8,9]. Arthritis affects approximately 59% of people aged 65 years and older and is the leading cause of disability [10]. The trend toward an aging society has severely increased the medical burden [11, 12, 13]. In addition, some of the challenges that older people continue to face are the adverse social impacts, such as the impact of negative stereotypes and discrimination against them. They may be affected by informal marginalization, such as being seen as less valuable and unable to contribute meaningfully, or by formal marginalization, such as being forced to retire. However, older persons can contribute a wealth of knowledge, skills, and experience, both inside and outside the workplace, and are often able and willing to contribute to many aspects of society [14].

To promote health and social connectedness, older individuals can engage in vol-unteer activities that provide a sense of purpose. Volunteering is rooted in altruism, so-cial support, and other social mechanisms [15]. In Japan, volunteer work increased by almost 10% from 2006 to 2011, and healthy seniors accounted for 85% of the volunteers who continued to contribute in 2012, effectively reducing issues such as social isolation and lonely deaths [4,16]. According to Herzog and House in "Productive Activities and Aging Well," volunteering among older individuals differs from that of younger individuals, as it is less tied to work and family obligations, providing more options and increasing the chances of positive health outcomes [17]. For instance, Ming-Ching Luoh conducted a study that found that 100 hours of volunteer work per year had a significant independent protective effect on the health and mortality of the elderly [18]. Exposure to natural environments has a stress-relieving and restorative effect on humans [19], and forest therapy has been shown to have a restorative effect on physiological aspects [20, 21]. Therefore, we aim to investigate the physiological and psychological restorative effects of preserving green spaces and engaging older adults in volunteer activities.

1.2 Satoyama activties and forest therapy

In Japan, Satoyama is a type of protected green space, and Satoyama volunteers face the problem of an aging society. Satoyama is noteworthy as it is agricultural land opposite remote mountains, and can be used to produce fuel, compost, grass ash, and other supplies [22, 23]. Now, people not only pass on the traditional functions of the forest to the next generation, but they can also reuse Satoyama in new ways to build a sustainable de-velopment environment using proper management techniques. The main characteristics of Satoyama activities include (1) sustainable management and utilization of resources; (2) life and cultural development through symbiosis with nature [24]; (3) sustainable use of green space to protect the biodiversity of the secondary forest [25, 26]; and (4) environmental education, forest bathing, natural observation, and forest operation [27].

The inspiration for forest therapy comes from the Shinrin Yoku practice in Japan, which means –forest bathing.l Forest therapy is a method of interacting with natural stimuli through physical activity or relaxation in and around forests. The purpose of this practice is to regenerate immune capacity through plant-derived, relaxing physiological effects [28]. Many studies have investigated the physiological and psychological relaxation effects of being in the forest on older adults. Physiological studies have shown that forest environments have benefits such as reducing the pulse rate [29], blood pressure [30], heart rate [31-34], and salivary cortisol concentration [35], and increased parasympathetic activity [29-32]. In addition, some simple interventions in the forest—such as leisurely walking, meditation, and recreational activities— contribute to psychological recovery, as evidenced by a reduction in depression, anxiety, fatigue, and stress levels, enhancing social cooperation, triggering a sense of well-being, and helping restore self-esteem [28-35]. Among the elderly, forest therapy can also alleviate insomnia in menopausal women [36]. Hong et al. also found that forest therapy for the middle-aged and elderly has a good effect on preventing Alzheimer_s disease [37] after conducting a senile forest therapy plan for 60 participants aged 50 years and above to prevent dementia.

1.3 Problem and Hypothesis

In an aging society, the active involvement of older adult volunteers is a valuable resource for both the community and the well-being of older adults. Research has shown that participation in Satoyama Green Space preservation activities has a psychologically rejuvenating impact on volunteers, enhancing their sense of purpose and involvement in volunteer activities. However, there are also studies that raise doubt about the psychological rejuvenation effects of Satoyama activities in subjective terms, suggesting that conventional sociological research methods have limitations in verifying their rejuvenation effects in light of the diversity of activities in Satoyama. To address this issue, this study employs a combination of subjective questionnaire formats and objective physiological measurements to examine the significance of Satoyama activities for older volunteers, with a control group of young individuals who have limited exposure to Satoyama. The study posits the following hypotheses: 1) There are differences in the physi-ological or psychological effects of participating in Satoyama activities in different seasons for older volunteers who have been engaged in such activities for a long time, and for younger individuals residing in cities; 2) There are differences in the experiences and emotions of young and old individuals in Satoyama; and 3) There are differences between seasonal activities in Satoyama. The aim of the study is to investigate the differences in the physiological or psychological effects of participating in Satoyama activities in different seasons between older adult volunteers and young people living in cities, the characteristics of the Satoyama landscape in different seasons, and the perspectives of different groups of individuals on Satoyama. Hence, this study will utilize both subjective and objective methods to offer a comprehensive understanding of the rejuvenation effects of Satoyama activities from multiple perspectives. By integrating physiological measurements and subjective questionnaires, this study aims to overcome the limitations of conventional sociological research methods and provide insights into the potential benefits of Satoyama activities for older adults and the wider community.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Location Context

As depicted in Figure 1, the "Forest around the Mountain" is located within the re-gion encompassing Gogo and Kanegasaku, in Matsudo City, Chiba Prefecture. The lati-tude of the area is 35.806886 and the longitude is 139.951435. The total area spans ap-proximately 2 hectares, with a dimension of 200 meters from north to south and 100 meters from east to west [38]. The volunteers responsible for maintaining the forest are students who participated in the Satoyama Volunteer Orientation Course held in Matsudo City in 2004. Since June 2005, these volunteers have been actively engaged in conservation activities within the forest, such as cleaning, mowing, and conducting ecological surveys (as illustrated in Figure 1).

Figure 1: The location of the –Forest around the Mountainsl. The red dotted lines were boundary line of the experimental site. The blue lines are the roads in the sample plot to delineate the specific area. The yellow numbers correspond to the names of these areas

2.2 Study Subject

To minimize the influence of insects in the forest and the muggy environment on the experiment, the participants, including both older adults and young individuals, consented to participate in the experiment between the months of March and April in 2021 and September and October in 2021. The study was conducted during these months to avoid the high mosquito population in the forest during the summer, and the thick clothing worn by participants during the winter, which would affect the accuracy of physiological measurement of heart rate using a real-time Bluetooth sensor attached to the skin. The study participants were individuals without heart disease, in good health, and capable of working for approximately 30 minutes without any difficulties. Older adults were aged 65 years or older and were volunteers from the "Forest around the Mountain" Nonprofit Organization (NPO) of Matsudo City. The young participants were mainly university and graduate students insured by the Health Mutual Aid Association. The first recruitment for the spring experiment was conducted from January to March in 2021, and the second recruitment for the autumn experiment was carried out from August to September in 2021 (as illustrated in Figure 2). The recruitment details included the purpose of the research, the description of the experimental content, the physical condition requirements for participants, and the contact information of the researchers. The recruitment method for older adults involved distributing flyers among them during Satoyama regular meetings, while social network services were used to recruit young participants. As the study involved handling sensitive personal information, ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Psychological Ethics Committee (protocol code 20-05) in November. The experiment was conducted from November 2021 to October 2022.

Figure 2: Participants from Forest around the Mountains and Chiba University

2.3 Experimental Design

As demonstrated in Table 1, a total of four experiments were carried out, with two experiments for the older adult volunteer group in March (n = 12) and two experiments for the young people group (n = 12) in April. To ensure the quality of the experiment, only six participants were involved in each experiment. The following steps were followed during each experiment: (1) upon arrival at the "Forest around the Mountains," the participants gathered in a designated "working square," as depicted in Figure 9; (2) the participants' body temperature was measured using an infrared thermometer; (3) the staff explained the flow of the experiment and the approval from the Human Research Ethics Review Board, and the participants signed a consent form; (4) before beginning the activities, the participants' blood pressure, Profile of Mood States 2nd Edition (POMS) [39], and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [40] were measured, and the participants were connected to a heart rate monitor; (5) the participants were given 10 minutes to observe nature from the entrance to the garden and fields; (6) after observing nature, the participants engaged in 30 minutes of work in the "working square," which included activities such as weeding, pruning branches, and simple logging (as illustrated in Figure 11); (7) the participants' blood pressure, POMS, and STAI were measured while they were performing Satoyama activities, and their heart rate was continuously monitored during both the nature observation and Satoyama work; (8) the heart rate measuring device was removed, and the experiment was completed. To accommodate the unique features of Satoyama, the NPO group of "Forest around the Mountain," led by Mr. Iki, provided helmets, mosquito repellent incense, sickles, and saws for this experiment.

|

No |

Time |

Survey Flow |

|

1 |

9:30–10:00 a.m. |

Meet at the –Forest around the Mountainsl |

|

2 |

10:00–10:10 a.m. |

Body temperature test and the disinfection of hands with alcohol |

|

3 |

10:10–10:30 a.m. |

Precautions for Satoyama activities and experiments |

|

4 |

10:30–10:50 a.m. |

Measuring blood pressure and heart rate and filling out POMS and STAI questionnaires before activity |

|

5 |

10:50–11:20 a.m. |

Nature observation (10 min), heart rate measurement |

|

6 |

11:20–11:50 a.m. |

Satoyama work (weeding, pruning branches, logging in 30 min), heart rate measurement |

|

7 |

11:50 a.m.–12 p.m. |

Blood pressure, POMS, and STAI questionnaires measured after Satoyama activities |

|

8 |

After 12 p.m. |

Removal of the heart rate measuring device and finishing the experiment |

Table 1: The experiment flow in the –Forest around the Mountains.l The Profile of Mood States 2nd Edition is abbreviated as POMS. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory is abbreviated as STAI.

2.4 Experiment’s Psychological Equipment and Questionnaire

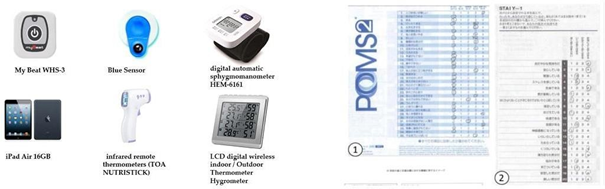

In accordance with the Japanese policy against COVID-19, infrared remote thermometers (manufactured by TOA NUTRISTICK) were utilized to measure the participants' temperature. If a participant's temperature was above 37.5°C, they were not eligible to participate in the experiment. A digital, wireless indoor/outdoor thermometer and hygrometer (manufacturer unknown) was used to measure the temperature and humidity of the "Forest around the Mountain." Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured before and after the experiment using a digital automatic blood pressure monitor (Omron HEM-6161), a portable battery-operated wrist measurement device. Heart rate and blood pressure were used as physiological parameters, with heart rate being continuously monitored using a heart rate blue sensor (My Beat WHS-3), which was connected to an iPad that captured and displayed the signal (as depicted in Figure 3).

The psychological parameters in this experiment were assessed using the Profile of Mood States 2nd Edition (POMS 2) and a new short version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) in Japanese (Figure 13). The POMS 2 is a reliable and effective psychological response measurement tool that contains 35 questions and is divided into six emotional states: anger-hostility (abbreviated as "A-H"), confu-sion-bewilderment (abbreviated as "C-B"), depression-dejection (abbreviated as "D-D"), fatigue-inertia (abbreviated as "F-I"), tension-anxiety (abbreviated as "T-A"), and vigor-activity (abbreviated as "V-A"). Each item was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 0 (none at all) to 4 (extreme), to gauge the participants' emotional states. The score of V-A was positively correlated with a positive emotional state, while the rest were negatively correlated. The state of anxiety component of the STAI was used to measure the participants' current anxiety level, with 20 questions being assessed using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). For the younger group, which included Chinese participants, simplified Chinese versions of the POMS and STAI were also adopted, with the content being identical to the Japanese version [39, 40].

Given the unique environment of Satoyama, which is different from a completely artificial natural environment, the forest is dense, wet, and populated with mosquitoes and insects, and there is a risk of falling branches and hand injury from the grass and trees. As such, necessary protective measures were taken, as shown in Figure 4. Participants were encouraged to bring full helmets, long-sleeved and long-legged clothing, and sturdy, easily movable shoes. The experiment organizers provided helmets, clean drinking water, gloves, mosquito repellent incense, and mosquito spray.

Figure 3: Physiological measuring devices and outdoor thermometers: My Beat WHS-3, Blue Sensor, ipad Air 16GB was used for Heart rate indicators; digital automatic sphygmomanometer HEM-6161 was used for blood pressure. CD digital Outdoor Thermometer Hygrometer for outdoor. Temperature and humidity measurement. Infrared remotethermometers was testing for higher-than-normal body temperature. Psychological scales: the Profile of Mood States 2nd Edition (POMS 2) and a new short version of the STAI in Japanese

Figure 4: Tools need participants to prepare by themselves. The image from the homepage of –Touch the Nature of Tokyo Go to Satoyama!l https://www.tokyo-Satoyama.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/go

2.5 Landscape Image Sketching Technique (LIST)

The novel contribution of this study is the utilization of the Landscape Image Sketching Tech-nique (LIST) questionnaire method, along with text mining using KH Coder. The method of text mining using KH Coder is described in detail in "Investigation with KHCODER 3." The LIST ques-tionnaire is a novel approach to analyzing the significance of the environment, which consists of a short sketch of a landscape image and a short verbal description of the sketch by the participant. This method provides a more comprehensive understanding of the environment by combining the verbal description with the visual representation. It is expected to reveal what participants are ob-serving and how they perceive their environment, offering new insights into the understanding of public images through landscape perception [41-45].

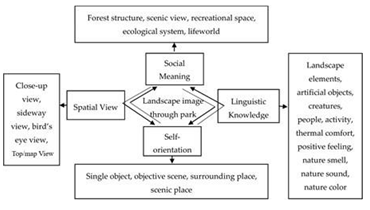

Nakamura [44] defines "landscape" in the Japanese context as a phenomenon with five char-acteristics: view, knowledge, direction, location network, and generation. The "view" refers to the limited spatial landscape seen by an individual standing on the ground. "Knowledge" encompasses linguistic elements used to represent the landscape. "Direction" refers to the subject-subject anchor in the environment that determines the individual's landscape value. "Place network" refers to the accumulation of experiences and their consequences in the environmental setting. "Generation" encompasses any change in the landscape. The visual and linguistic data collected were analyzed based on four landscape conditions (landscape image aspects): (1) identification of landscape ele-ments, (2) structure of human-environment relationships, and (3) meaning of place. Each landscape image sketch was categorized into these landscape image aspects using an inventory method. The presence of variables in the landscape image sketch was recorded as "1," while "0" indicated their absence. A chi-square test [46] was applied to compare the variables of the linguistic and visual data of the landscape images. Independent samples t-test analyses were conducted to examine the differences between Satoyama volunteers and non-Satoyama volunteers, and between Satoyama images and seasons and Satoyama activities (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Landscape image sketches of Satoyama image. Adapted from –Landscape image sketches of forests in Japan and Russia,l by H. Ueda, T. Nakajima, N. Takayama, E. Petrova, H. Matsushima, K. Furuya, and Y. Aoki, 2012, Forest Policy and Economics, 19,

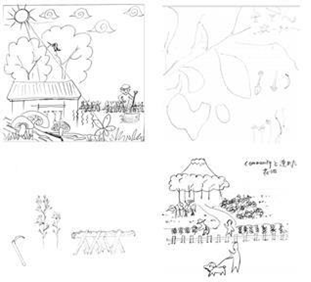

Figure 6: Young people_s landscape image sketches of Satoyama

Figure 7: Older adult volunteers_ landscape image sketches of Satoyama.

To assist in understanding the content of the painting, the LIST questionnaire required the subjects to extract keywords from their drawings and provide a 100-word description of them. In our study, the analysis was conducted by professionals from the Horticultural Research Division, using the diagrams in Figures 6 and 7. If the upper-right corner of the figure in Figure 6 shows a close view of the leaves, select Close-up view in the spatial view and replace it with 1 in the corresponding table. For example, if trees appear in Figure 7 and it is not possible to determine whether they are trees or stakes if the keyword "tree" is included in the subject's own description, record "tree" in the Linguistic Knowledge section. "If there is no "tree" in the bottom left corner of Figure 7, then it is marked as "0".

2.6 Analysis Methods

The blood pressure data used in the experiment were divided between older vol-unteers and younger people and before and after the Satoyama activity. For mean heart rate values, we considered the mean heart rate values per minute during nature observation and Satoyama work as well as the mean heart rate for each group of younger and older volunteers for analysis. Since the sample size is less than 13 (n = 12) and does not satisfy the normal distribution, the Wilcoxon signed- rank test [46] was used to assess the differences in mean psychophysiological values between the two groups before and after the Satoyama activity. Analyses of LIST was performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Quantitative content analysis was performed using KH Coder 3 to quantify the highest degree of centrality. Interpretive linguistic data of landscape images were examined by automatically extracting common words from the data, statistically analyzing them to obtain a complete landscape image, and exploring features of the data while avoiding researcher bias.

3. Results

3.1 Environment, Participants, and Satoyama Activity Information

The experiment was measured using an LCD, digital, wireless, indoor/outdoor thermometer and hygrometer and was completed over 8 days: March 23, 29 and April 24, 28 of spring; September 20 September 27 October 22 October 24 of

autumn (Table 12).

The environmental physical indicators were measured in three times per experi-ment, we used the average values as results. The temperatures on these 8 days were 15.2 ± 2.66 °C, 23.5 ± 2.34 °C, 20.825 ± 1.08 °C, and 22 ± 0.88 °C, 17.5 ± 4.88°C, 18.5 ± 3.33°C, 19.15 ± 1.08°C, 24.56 ± 2.01°C, respectively. The relative humidity was as follows: 54.25 ± 8.22

%rh, 75.25 ± 6.95 %rh, 39 ± 0.82 %rh, 51.25 ± 1.71 %rh, 52.99 ± 5.77%rh, 5.66 ± 6.95%rh, 43± 0.23%rh, and

41.33±2.71%rh respectively. The luminosity in Klux was 40.03 ± 10.60, 26.77 ± 12.68, 28.75 ± 22.27, 24.67 ± 13.87,

35.55 ± 18.34, 33.91 ± 15.43, 29.11 ± 13.28, 23.66±14.17. Sound in dB(A) was 40.9 ± 1.3, 44.5 ± 3.12, 41 ± 1.41, 47.33

± 5.86, 46.9 ± 0.5, 39.2 ± 2.87, 42 ± 1.41, and 41.09 ± 3.67 (Table 2).

|

Parameters Mean ± SD |

23-Mar |

29-Mar |

24-Apr |

28-Apr |

20-Sep. |

27-Sep. |

22-Oct. |

24-Oct. |

|

Temperature/°C |

15.2 ± 2.66 |

23.5 ±2.34 |

20.825 ± 1.08 |

22 ± 0.88 |

17.5 ± 4.88 |

18.5 ± 3.33 |

19.15 ± 1.08 |

24.5 ± 2.01 |

|

Relative humidity/% |

54.25 ± 8.22 |

75.25 ± 6.95 |

39 ± 0.82 |

51.25±1. 71 |

52.99 ± 5.77 |

5.66 ± 6.95 |

43± 0.23 |

41.33±2. 71 |

|

Light/Klux |

40.03 ± 10.60 |

26.77 ± 12.68 |

28.75 ± 22.27 |

24.67±13 .87 |

35.55 ± 18.34 |

33.91 ± 15.43 |

29.11 ± 13.28 |

23.66±14 .17 |

|

Sound/dB(A) |

40.9 ± 1.3 |

44.5 ± 3.12 |

41 ± 1.41 |

47.33 ± 5.86 |

46.9 ± 0.5 |

39.2 ± 2.87 |

42 ± 1.41 |

41.09 ± 3.67 |

Table 2: The environmental physical indicators of spring and autumn experiment

Individual data for the older volunteer group and the young people in spring and autumn are combined in Table 3. Where detailed individual data on spring volunteers and young people are already available in Chapter 5 (which can be referred to pages 48 to 49 of this paper), the spring values are described in Chapter 6 as a reference item together with the autumn data. The average age of young people was 25.4±1.56 in spring and 25.25±1.66 in autumn; the average age of older volunteers was 72±5.08 in spring and 72.5±4.8 in autumn. 58.30% of the older volunteers were men and 41.70% were women in spring. The ratio of males to females in the younger group was half, and this data was consistent with the autumn. Since young people are school students, they are not working. However, the working status of the older people was different in spring and autumn, 83.30% were retired in spring and 91.70% in autumn. The final education of the older volunteers in the spring was as follows: 25% had a high school education; 58.30% had attended college, and 16.70% had attended graduate school. The final education of the young people was as follows: 75% had a college education and 25% had attended graduate school. The final educational attainment of the older volunteers in the autumn was as follows: 8.30% had a high school education; 75% had attended college, and 16.70% had attended graduate school. The final education of the young people was as follows: 50% had a college education and 50% had attended graduate school.

Spring monthly income is measured in Japanese yen (JPY). For the elderly group, 8.30% earned less than 100,000 JPY; 41.70% earned between 100,000 and 200,000 JPY; 41.70% earned between 200,000 and 300,000 JPY, and 8.30% earned more than 300,000 JPY; conversely, 91.70% of young people earned less than 100,000 JPY, and 8.30% earned between 100,000 and 200,000 JPY between. For the elderly group in the autumn, 8.30% earned less than 100,000 yen; 50% earned between 100,000 and 200,000 yen; 41.70% earned between 200,000 and 300,000 yen; and none of the young people earned more than 100,000 yen. Considering that the students' main job is studying at school, this income is only their usual source of part-time work and does not include parental sponsorship.

|

Parameter |

Spring(n=24) |

Autunm(n=24) |

|||

|

young people |

older adult volunteers |

young people |

older adult volunteers |

||

|

Age |

25.4±1.56 |

72±5.08 |

25.25±1.66 |

72.5±4.8 |

|

|

Gender |

Male |

50% |

58.30% |

50% |

58.30% |

|

Female |

50% |

41.70% |

50% |

41.70% |

|

|

Employment Status |

Yes |

0% |

16.70% |

0% |

8.30% |

|

No |

100% |

83.30% |

100% |

91.70% |

|

|

Educational background |

High school |

0% |

25% |

0% |

8.30% |

|

University |

75% |

58.30% |

50% |

75% |

|

|

Graduate school |

25% |

16.70% |

50% |

16.70% |

|

|

Income (JPY/month) |

Less than¥100,000 |

91.70% |

8.30% |

100% |

8.30% |

|

¥100,000~200,00 0 |

8.30% |

41.70% |

0% |

50% |

|

|

¥200,000~300,00 0 |

0% |

41.70% |

0% |

41.70% |

|

|

More than¥300,000 |

0% |

8.30% |

0% |

0 |

|

|

Smoking behavior |

Yes |

8.30% |

8.30% |

16.70% |

25% |

|

No |

91.70% |

91.70% |

83.30% |

75% |

|

|

Alcohol use |

Yes |

25% |

58.30% |

58.30% |

66.70% |

|

No |

75% |

41.70% |

41.70% |

33.30% |

|

|

Sleeping time(hours) |

~5h |

0% |

0% |

0% |

8.30% |

|

5~7h |

33.30% |

41.70% |

33.30% |

66.70% |

|

|

7~9h |

66.70% |

58.30% |

58.30% |

25% |

|

|

9h~ |

0% |

0% |

8.30% |

0 |

|

|

Sports activities/month |

5.583±5.5 |

10.92±8.979 |

3.42±3.32 |

9.33±8.08 |

|

|

using urban green space/month |

4.33±5.07 |

4.67±3.774 |

4.17±4.22 |

4.08±2.5 |

|

|

Satoyama activities /month |

0.25±0.866 |

2.92±1.929 |

0 |

3.83±1.70 |

|

|

Satoyama knowledge |

not at all know |

25% |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

not very know |

8.30% |

41.70% |

0 |

0 |

|

|

neutral |

33.30% |

25% |

41.70% |

8.30% |

|

|

know |

25% |

33.30% |

50% |

50% |

|

|

know well |

8.30% |

0 |

8.30% |

41.70% |

|

Table 3: Participants' information of spring and autumn experiment

average age of older volunteers was 72±5.08 in spring and 72.5±4.8 in autumn. 58.30% of the older volunteers were men and 41.70% were women in spring. The ratio of males to females in the younger group was half, and this data was consistent with the fall. Since young people are school students, they are not working. However, the working status of the older people was different in spring and autumn, 83.30% were retired in spring and 91.70% in autumn. The final education of the older volunteers in the spring was as follows: 25% had a high school education; 58.30% had attended college, and 16.70% had attended graduate school. The final education of the young people was as follows: 75% had a college education and 25% had attended graduate school. The final educational attainment of the older volunteers in the fall was as follows: 8.30% had a high school education; 75% had attended college, and 16.70% had attended graduate school. The final education of the young people was as follows: 50% had a college education and 50% had attended graduate school. Spring monthly income is measured in Japanese yen (JPY). For the elderly group, 8.30% earned less than 100,000 JPY; 41.70% earned between 100,000 and 200,000 JPY; 41.70% earned between 200,000 and 300,000 JPY, and 8.30% earned more than 300,000 JPY; conversely, 91.70% of young people earned less than 100,000 JPY, and 8.30% earned between 100,000 and 200,000 JPY between. For the elderly group in the fall, 8.30% earned less than 100,000 yen; 50% earned between 100,000 and 200,000 yen; 41.70% earned between 200,000 and 300,000 yen; and none of the young people earned more than 100,000 yen. Considering that the students' main job is studying at school, this income is only their usual source of part-time work and does not include parental sponsorship.

In terms of lifestyle habits, the data on smoking were identical between the two groups in the spring, with 8.30% of smokers and 94.70% of non-smokers. However, in the autumn 25% of the older volunteers smoked compared to 16.70% of the younger ones. In addition, 58.30% of the elderly had drinking habits in the spring compared to 25% of the young people; the autumn showed almost the same habits with 66.70% of the older adult volunteers drinking alcohol compared to 58.30% of the young people. Data related to sleep habits showed that 41.70% of seniors and 33.30% of young people slept between 5 and 7 hours on a 24-hour day in spring, with 58.30% and 66.70% of them sleeping between 7 and 9 hours. In the autumn 8.30% of older people sleep less than 5 hours, 66.70% between 5 and 7 hours, and 25% between 7 and 9 hours; for young people, the figures are 33.30% between 5 and 7 hours, 58.30% between 7 and 9 hours and 8.30% more than 9 hours (Table 3).

For our research, we put forward some questions as follows: how many times you exercise every month, use urban green space, and how many times do you want to do activities in Satoyama. And how much you know about Satoyama. We found that the exercise frequency of the elderly was much higher than that of the young in spring and autumn, with an average of 10.92 ± 8.979 times a month in spring and 9.33 ± 8.08 times in autumn. The exercise frequency of young people was 5.583 ± 5.5 in spring and 3.42 ± 3.32 in autumn. Both sides have similar chances to use urban green space. The activity frequency of the older adult volunteers in autumn (3.83 ± 1.70) will be slightly higher than that in spring (2.92 ± 1.929), while for young people, no one has the experience of the activities in autumn, which is 0.25 ± 0.866 in spring. In terms of the knowledge of He Satoyama, the number of young people distributed from "not at all know" to

"know well" in spring, and the answer value of older adult volunteers was concentrated between "not very know" (41.70%) and "know well" (33.30%). In autumn, the answers of both young and old volunteers were concentrated in the range between "neutral" and "know well". According to the autumn data, 41.70% of young people knew about Satoyama at a moderate level and 8.30% knew about Satoyama very well, which is the reverse for the older adult volunteers. And 50% of people know about Satoyama.

3.2 Reliability Analysis of Physiological and Psychological Subsection

The parameters of participants in Satoyama activities (before and after working) are provided in Table 14. The overall parameters show internal consistency (0.5–0.9). The results indicate that heart rate and blood pressure, as physiological parameters, had good internal consistency (more than 0.7) except the heart rate of young peo-ple, while POMS and STAI scores had good internal consistency (more than 0.7). The alpha reliability of heart rate of older adult volunteers was 0.511 with internal con-sistency, while it of young people was -1.660 without internal consistency. For blood pressure, it was 0.684 and 0.863, respectively, for the two groups. Cronbach_s α re-liability analysis between the older adult volunteers (n = 12) and young people (n = 12) showed that the reliability of the POMS score for the two groups was 0.767 and 0.795 with good internal consistency, respectively; and that of the STAI score was 0.806 and 0.680 with good internal consistency, respectively. The internal consistent reliability of the heart rate data for young and older adult volunteers in the spring was 0.336, 0.463, 0.758, and 0.405. This indicates that only the heart rate results for the older adult volunteers in the spring were reliable, while the rest were unsatisfactory. Blood pressure was 0.684, 0.808, 0.863, and 0.744, respectively, all showing very reliable internal consistency. alpha reliability for the POMS data was 0.767, 0.898, 0.795, and 0.569. all were very good reliability except for the autumn older adult volunteers who were 0.569 indicating acceptable internal consistency. alpha reliability for the STAI data was 0.806, 0.795, and 0.569. The internal consistency was very good, except for the autumn youths, for whom it was below the standard value. STAI data was 0.806, 0.795, and 0.569. The internal consistency was very good, except for the autumn youths, for whom it was below the standard value.

|

Cronbach’s α |

||||

|

Parameter |

Young People (n = 12) |

Older Adult Volunteers |

||

|

(n = 12) |

||||

|

Spring |

Autumn |

Spring |

Atumn |

|

|

HR (RRI) |

0.336 |

0.463 |

0.758 |

0.405 |

|

Blood Pressure |

0.684 |

0.808 |

0.863 |

0.744 |

|

POMS |

0.767 |

0.898 |

0.795 |

0.569 |

|

STAI |

0.806 |

0.298 |

0.68 |

0.901 |

Table 4: Cronbach_s α reliability analysis between older adult volunteers (n = 12) and young people (n = 12) in spring and autumn.

3.3 Physiological Indicators

3.3.1 Blood pressure indicators

Since there were only twelve variables in each test, we took a non-parametric Wil-son's sign test to compare the differences in blood pressure in different populations be-fore and after the Satoyama activity.

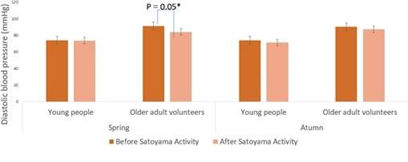

It was found that there was no significant change in systolic and diastolic blood pressure in the spring in the older adult volunteers, except for the other groups. The systolic blood pressure in this group was 153.33 before the Satoyama activity and 137.92 after the Satoyama activity; the diastolic blood pressure was 91.58 and 84.08, with a significant difference (Figure 8), (Figure 9).

Figure 8: Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) compared with before and after Satoyama activities of young people and older adult volunteers. * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01

Figure 9: Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) compared with before and after Satoyama activities of young people and older adult volunteers. * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01

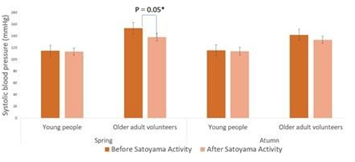

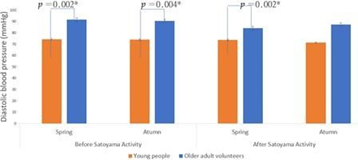

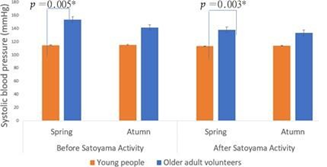

A comparison of blood pressure changes in young and old people before and after Satoyama activity was performed in spring and autumn as Figures 10, and 11 shown. The systolic blood pressure was found to be significantly different between the elderly and the young in the spring, both before and after the Satoyama activity, but not in the autumn. The values were 114.58 for the young and 153.33 (*p ≤ 0.05) for the elderly before the spring Satoyama activity, 113 for the young and 137.92 (*p ≤ 0.05) for the elderly after the spring Satoyama activity, and no significant difference between the diastolic blood pressure of the young and the elderly before and after the Satoyama activity only in the autumn, but the rest were significantly different. The diastolic blood pressure was 74.25 in young people and 91.58 (*p ≤ 0.05) in elderly people before the spring Satoyama activity, and the comparative values were 74.17 and 90.42 (*p ≤ 0.05) before the autumn Satoyama activity, and 73.75 in young people and 84.08 (*p ≤ 0.05) in elderly people in the spring after the Satoyama activity.

The changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure were compared between spring and autumn and it was found that there would not be a significant difference between seasons. Therefore, we will not expand on this, and if the amount of data is expanded, the different seasons in the Satoyama region, etc. might be tested again

Figure 10: Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) compared with young people and older adult volunteers in spring and autumn. * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01

Figure 11: Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) compared with young people and older adult volun-teers in spring and autumn. * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01

3.3.2 Heart rate indicators

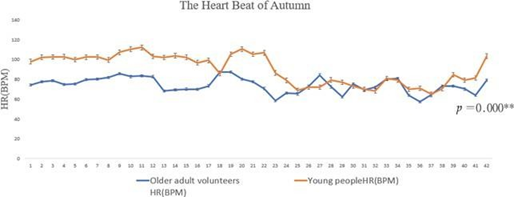

The reliability of the heart rate values in the spring was found to be low during the reliability test, so only the heart rate values per minute of the young and the old were compared here in the autumn and significant differences were found between them. It was fod from the graph that the heart rate values of the young people were consistently higher than those of the elderly until the end of the Satoyama activity when the overlap part started (Figure 12).

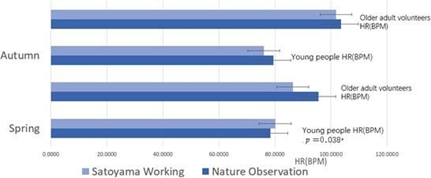

Figure 13 compares whether there is a significant difference in the change in heart rate between the two conditions of Satoyama work and natural observation, which lasted for ten minutes and had only ten data, so we used the same non- parametric test of Wilson's sign test. We found that all of the natural observation heart rates were higher than those of the Satoyama work, even though the natural observation was just a walk and the Satoyama work was doing gardening activities such as weeding and repairing tree branches. And there was a significant difference between 80.1 in nature observation and 78.41 (* p ≤ 0.05) in Satoyama work in spring for young people.

Figure 12: Differences in heart rate between the elderly and young people during activities in Satoyama in autumn. * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01

Figure 13: Analysis of the difference between the natural observation rate of young people and the labor center rate of old people in spring and autumn by means of independent sample T-test and comparative mean value method. * p ≤ 0.05,** p ≤ 0.01

3.4 Psychological indicators

A non-parametric Wilson sign test was taken to compare the values of POMS, STAI in different seasons and it was found that only the F-I values indicating Fatigue-inertia were significantly different among the young people after the Satoyama activity. The values were 10.25 ± 3.44 in spring and 6.83 ± 3.49 in autumn (* p ≤ 0.05), which indicates that spring is the first time that young people participate in Satoyama activities, and they feel more strongly about fatigue (Table 5).

|

Psychological Parameters |

Elder Volunteers |

Young People |

|||||

|

Mean ± SD |

p-Value |

Mean ± SD |

p-Value |

||||

|

Spring |

Atumun |

Spring |

Atumun |

||||

|

Mood State (POMS) before Satoyama activity |

Anger-hostility(A-H) |

2.17 ± 2.04 |

2.67±2.27 |

0.602 |

5.583 ± 3.23 |

5.58±4.1 |

0.838 |

|

Confusion- bewilderment(C-B) |

1.75 ± 2.09 |

2.58±2.07 |

0.385 |

8.17 ± 4.09 |

7.92±4.56 |

0.442 |

|

|

Depression- dejection(D-D) |

1.67 ± 1.61 |

5.25±13.34 |

0.356 |

7 ± 4.07 |

7.33±5.33 |

0.905 |

|

|

Fatigue-inertia (F-I) |

2.75 ± 3.60 |

3.33±3.06 |

0.609 |

10.5 ± 5.05 |

9.33±5.41 |

0.504 |

|

|

Tension-anxiety(T- A) |

1.92 ± 1.73 |

3.42±2.61 |

0.153 |

7.83 ± 3.74 |

8.33±4.90 |

0.646 |

|

|

Vigor-activity(V-A) |

10.08 ± 4.62 |

9.75±4.29 |

0.859 |

12.83 ± 4.97 |

10.58±4.03 |

0.285 |

|

|

Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) |

0.17 ± 7.60 |

3.92±12.28 |

0.508 |

26.25 ± 20.22 |

27.92±25.20 |

0.092 |

|

|

Mood State (POMS) after Satoyama activity |

Anger-hostility(A-H) |

0.08 ± 0.29 |

1.75±4.59 |

0.144 |

2.08 ± 2.64 |

2.75±2.83 |

0.523 |

|

Confusion- bewilderment(C-B) |

1.25 ± 1.60 |

0.92±2.02 |

0.478 |

5.42 ± 3.65 |

4.83±3.74 |

0.875 |

|

|

Depression- dejection(D-D) |

1.25 ± 2.18 |

0.42±1.44 |

0.248 |

3.83 ± 4.43 |

4.08±3.55 |

0.725 |

|

|

Fatigue-inertia (F-I) |

3.08 ± 3.29 |

2.58±3.53 |

0.878 |

10.25 ± 3.44 |

6.83±3.49 |

0.02* |

|

|

Tension-anxiety(T- A) |

0.92 ± 1.51 |

1.33±1.93 |

0.588 |

5.33 ± 4.99 |

5.58±3.39 |

0.906 |

|

|

Vigor-activity(V-A) |

12.83 ± 5.03 |

14±4.92 |

0.529 |

14.42 ± 4.98 |

11.25±3.39 |

0.157 |

|

|

Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) |

6.25 ± 7.79 |

7±14 |

0.656 |

12.05 ± 19.29 |

12.83±16.94 |

0.098 |

|

|

State Anxiety (STAI) |

Before Satoyama Activity |

32.83 ± 8.26 |

33.67±8.53 |

0.635 |

34.5 ± 8.24 |

40.58±9.64 |

0.098 |

|

After Satoyama Activity |

29.17 ± 5.6 |

30.25±9.15 |

0.799 |

31.5 ± 8.97 |

34.08±8.53 |

0.348 |

|

Table 5: Comparison of POMS, STAI mean and P-value of different seasons for young and volunteer elderly before and after Satoyama activity. * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01

Comparison of indicators before and after Satoyama activity. In spring and autumn, we will compare the significant differences between the psychological indicators of young people before and after the Satoyama activity. Five values were found to be significantly different in spring, and three were extremely significant. In the autumn, 5 values differed significantly and 7 differed significantly. There was more significant post-Satoyama activity recovery in the autumn than in the spring. Significant differences in the spring for older adult volunteers were A-H, T-A, V-A; differences in the total indicator TMD and its significance. In the autumn, significant differences were D-D, T-A; differences and their significance were C-B, V-A, TMD, and anxiety scale STAI. young people had significant differences in spring with T-A, TMD; differences and their significance were A-H, D-D. In the autumn, significant differences were TMD, STAI; highly significant were A-H, C-B, T-A (Table 6).

Table 6: Comparison of indicators before and after the Satoyama event

3.5 Landscape image sketches of Satoyama image

Using Spearman's two-tailed test, younger and older adults were more likely to differ significantly in spatial view, self- orientation. close-up, Top/map View difference was significant; Sideway, Objective Scene difference was highly significant. surrounding place difference and its Surrounding place was significant. Significant differences were found between seasons in the social meaning of the forest, i.e., Forest Structure. Older people and younger people have different perspectives on the landscape of Satoyama. Spring and autumn have different social meanings of forest structure. It also shows that this small area of green space in the city can bring a variety of different feelings when it is used as a Satoyama, providing a site that can produce different perspectives, organisms, etc. In spring and autumn, there is a social inconsistency in the structure of the forest (Table 7).

|

Close- up |

Sidew ay |

Top/map View |

Surrounding place |

Objective Scene |

Forest Structure |

|

|

Young people and older adult volunteers |

0.033* |

0.005* * |

0.043* |

0.000*** |

0.003** |

- |

|

Spring and autumn |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.001** |

Table 7: P-value of Linguistic Knowledge of Spatial view, Self-orientation and social meaning

Linguistic Knowledge are divided into: –Landscape elementl, –artificial objectsl, –creaturesl, –peoplel, –activel, –thermal comfortl, –Feelingl, –nature smelll, –nature soundl, and –nature colorl (Table 8). The landscape elements that differed significantly between young and old volunteers were –squarel, and man-made objects were –squarel and –sawl. Among the creatures there were –foodl, –animalsl, –wormsl, –potatoesl, –golden orchidl, and –nature colorl. –Golden Orchidl,

–Canola Flowersl, –Budl, –Bird –. People have Human expression differences. There is a difference in the activity

–Lumberingl and –Learningl. Unusual, nature, and peace are different in expressing their feelings. For spring and autumn,there is no difference in the landscape elements. Artifacts with the same saws are different: –worml, –potatol, –golden orchidl, –canola flowersl, –canolal. Canola Flowersl, –Budl. There is a significant difference in the activity –learningl. There are also differences in expressing their feelings more often, such as the natural colors –greenl, –beautifull, –Livelyl. The positive vocabulary also becomes more expressive of the experience: –Comfortablel, –Unusuall, –Peacel. Figures 26 and 27 represent the different perspectives and positions of Satoyama as associated with older and younger people, respectively.

|

P-value of Linguistic Knowledge |

||||||||

|

young people and older adult volunteers |

Food |

Lumbering |

animal |

Saw |

Human |

worm |

Potato |

Golden Orchid |

|

0.038* |

0.001** |

0.007* |

0.002* |

0.018* |

0.02* |

0.039* |

0.039* |

|

|

Spring and autumn |

- |

Comfortable |

Beautiful |

Saw |

Lively |

worm |

Potato |

Golden Orchid |

|

- |

0.022* |

0.001** |

0.005** |

0.005* * |

0.003* * |

0.043* |

0.043* |

|

|

young people and older adult volunteers |

Canola Flowers |

nature |

Study |

Unusual |

Bud |

Bird |

Squar e |

Peace |

|

0.039* |

0.017* |

0.017* |

0.039* |

0.043* |

0.022* |

0.022* |

0.043* |

|

|

Spring and autumn |

Canola Flowers |

Unusual |

Study |

- |

Bud |

- |

Green |

Peace |

|

0.043* |

0.043* |

0.022* |

- |

0.043* |

- |

0.022* |

0.043* |

|

Table 8: P-value of Linguistic Knowledge

3.6 Text mining of Satoyama

According to our findings (Figure 14), the word "tree" has a stronger correlation coefficient with older people, at 0.38, compared to younger people, with a coefficient of 0.11. In contrast, the correlation coefficient of "forest" is 0.29 for young people and 0.12 for older people. Other words that exhibit strong correlations include "nature" with a coefficient of 0.28, "happy" with 0.21, "beautiful" with 0.17, "Satoyama" with 0.17, and "good" with a stronger correlation coefficient of 0.17 with older adult volunteers. Interestingly, "bird" has a separate coefficient with older adult volunteers, while "beautiful" and "square" have separate coefficients with young people. As a result, we utilized these three words as keywords to conduct a KWIC search, resulting in the following sentences, with the searched keywords bolded: "I saw little birds even in the trees around."; "The birds are chirping. You can stroll freely." "It was a beautiful day, so I came to Tokiwadaira early in the morning to participate in the Satoyama activity, and I used the birch and other tools to loosen the soil and pull weeds." "This opened a beautiful path through the forest." "To make the square for children to play, the trees were carried and collected, hoping to make the space bigger."

It was valuable to identify words that held individual significance and had high frequency in the central vocabulary.

Doing so helped us to understand what caught the attention of older adult volunteers who had spent a long time in Satoyama, as well as young people who had little experience with it. Interestingly, the older volunteers who were familiar with Satoyama rarely mentioned it, while it held strong relevance for the young people. Therefore, we searched for relevant sentences using KWIC. To further understand why some words had a high degree of coefficient with young people and others with the older adult volunteers, we conducted a KWIC analysis of high-frequency words linked separately to each group. We selected "Satoyama" and "happy" for young people, and "good," "child," "space," and "root" for older adult volunteers.

For instance, a young person's comment read, "When I first came to Satoyama, I didn't know the environment well, and the grass and forests were dark, so I was worried about the unknown workl; –My heart calmed down, and the scene that

left the deepest impression on me was the scene where I entered the Satoyama along the path." Another young person stated, "Through today's activities, I felt that nature is alive and well, and I felt happy and relaxed in this environment." On the other hand, an older adult volunteer said, "I think it would be good to plant as many dry fruits as possible, which are suitable for Satoyama," while another remarked, "It is a good environment for activities." An older volunteer also commented, "In order to make the square for children to play, the trees were carried and collected, and the useless ones were thrown to the garbage place," while another mentioned, "Digging the roots of plants with tools was very hard but very rewarding.".

Figure 14: Impressions of Satoyama activities Co-occurrence network of words by participants variables

In Figure 15, taking spring as the base, the coefficient with spring is high and the coefficient with Autumn are: –treel has a coefficient of 0.41 and autumn is 0.26. –forestl has a coefficient of 0.37 and autumn is 0.04. –funl has a coefficient of

0.22 and autumn is 0.8. The coefficient is 0.22 for –forestl and 0.8 for autumn. The terms –child (0.17)l, space (0.17), and root (0.17), which have high coefficient with autumn alone, tell us directly that the main activity that occurs in autumn is the elimination of plant roots in order to create open spaces for children. In order to find out why some words are high in

terms of efficiency in spring and some in terms of efficiency in autumn, we conducted KWIC analysis on their high- frequency words that are most likely to appear. Spring is related to –forestl, –funl and –environmentl. –Childrenl,

–spacel and –rootl are related to autumn. Since the autumn-related vocabulary is the same as that of the older adult volunteers, I will not repeat it again. Only three terms from the spring were searched.

–Together with Mr. Iki in the forest, we cut down trees that had autumnen due to the typhoon and placed them on both sides of the road.l; –You can enjoy the scent of the forest with the sunlight filtering through the trees.l; It is a very lively nature, and it is fun. Feel the nature and have fun with the members you worked with. Have fun with everyone. People are having fun in it. Collaborative work with colleagues is fun. –I carried a tree with grandpa behind me. China-Japan exchanges are very fun.l

Figure 15: Impressions of Satoyama activities Co-occurrence network of words of spring and autumn

Experiencing Satoyama engages all five senses, from the chirping of birds to the beauty of the surroundings and the essential presence of the square. Using KWIC to in-vestigate the keywords used by young people to describe Satoyama, we found that the dimness of the forest and the unknown can cause tension and a rapid heartbeat, ex-plaining why young people's heart rates are faster during natural observation. Young people report feeling very happy during Satoyama activities and gaining a lot of knowledge, which is consistent with the appearance of "unusual," "study," and the sci- entific names of flowers in the LIST. Conversely, elderly volunteers often use "good" to describe their experiences. Satoyama relaxes their bodies, calms their minds, and effec-tively restores their physical and mental health. They are also more interested in how Satoyama can benefit others, such as creating squares for children to play in, even if it means hard work digging up weed roots. In summary, participating in Satoyama activities in the forest, particularly during the spring, is a fascinating experience.

4. Discussion

Our study showed that Satoyama provides a positive experience for physical and mental health recovery, regardless of the season, as there were no significant differences between spring and autumn in terms of physical health [47]. Our findings also revealed that blood pressure levels in older adults were typically higher before Satoyama activities and returned to normal levels after such activities in the spring [47]. We compared older and younger people's mental health in different seasons and found that older adults experienced better mental health in the autumn, especially after Satoyama activities, which did not differ significantly from the data of younger people. During the reliability test, we found low reliability of heart rate values in the spring. Hence, we compared only the heart rate values per minute for the young and the old in the autumn, and we found significant differences between them. The heart rate values of young people were consistently higher than those of older people until the end of the Satoyama activity when the overlap part started [48]. Surprisingly, we found higher heart rates for all the natural observations than for the Satoyama work, despite the former being just walks and the latter involving weeding and repairing branches [48].

Regarding psychological effects, we found that only the Fatigue-inertia (F-I) scale showed a significant decrease in the autumn compared to the spring after young people completed Satoyama activities. This could be due to the fact that young people were exposed to Satoyama for the first time in the spring during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the lack of adaptation to Satoyama activities may have prevented rapid recovery from fatigue [49]. Furthermore, some activities related to logging and pruning can cause accidents and injuries, even to professionals [50, 51].

In comparing the indicators before and after Satoyama activities, significant differences were observed among older volunteers in spring for Anger-hostility (A-H), Tension-anxiety (T-A), Vigor-activity (V-A), and TMD, whereas in autumn, significant differences were found in Depression-dejection (D-D), Tension-anxiety (T-A), Confu-sion- bewilderment (C-B), Vigor-activity (V-A), TMD, and the anxiety scale STAI. For young people, significant differences were observed in spring for T-A, TMD, A-H, and D-D, while in autumn, significant differences were found in TMD, STAI anxiety scale, A-H, C-B, and T-A. Although the difference between STAI and C-B in the spring was not significant, both values were significant in the autumn.

Moreover, the difference between C-B and D-D in the spring was also significant in the autumn after Satoyama activities among older adults. This suggests that overall, mental health recovers better in autumn, and older people recover very

well mentally in both spring and autumn. It is plausible that on the one hand, the unique beauty of autumning leaves and red leaves during autumn in Japan [52] may contribute to this effect, and on the other hand, as illustrated by LIST, older adult volunteers and young people hold distinct perspectives and attitudes towards Satoyama scenery. This small green space within the city provides a diverse range of emotional experiences when utilized as a Satoyama [53, 54], creating a site that generates diverse perspectives. In spring and autumn, there is a social inconsistency within the forest's structure, and the sounds of birds chirping in Spring, the beauty of Satoyama, and the essential square in Satoyama provide a multisensory experience for individuals [55-58]. For example, the group of older adult volunteers expressed their feelings using the word "good." Satoyama enabled their bodies to relax, and their minds to calm down, and facilitated effective physical and mental recovery. Furthermore, they focused on how they could use Satoyama to benefit others. Despite the arduous task of dealing with weed roots, useful work like creating spaces for children to play in is worthwhile through KWIC analysis. Besides, it was found that the enclosure of the forest causes the light to dim, and the sense of uncertainty can lead to tension and a rapid heartbeat, possibly explaining why young people felt tense and their heart rate is higher during natural observation in the spring Satoyama study [59]. Young people feel that the Satoyama activities give them a very happy impression and they can learn a lot, which is in line with the appearance of "unusual", "study" and the scientific name of flowers in LIST [60].

5. Conclusion

The study aimed to address several questions related to the effects of participating in Satoyama activities for older adult volunteers. Firstly, the study compared the physiological and psychological effects of participating in Satoyama activities in different seasons for older volunteers who have been engaged in these activities for an extended period and for younger individuals living in urban areas. The results showed that there was no significant difference in the physiological aspects of participating in Satoyama activities between the seasons. However, the study found that the psychological effects of participating in these activities were more restorative in autumn than in spring, with a higher number of recovery indicators. This suggests that repeated exposure to Satoyama can enhance the benefits of participation, as young people may feel more familiar and less anxious after their second visit.

Secondly, the study aimed to identify differences in the experiences of older adult volunteers and young individuals in Satoyama. The results showed that there were dif-ferences in the experiences of these two groups, demonstrating the richness of Satoyama experiences. The study found that older adult volunteers were more inclined to calm the present and transform Satoyama for the present and future, while young individuals were more likely to perceive new things with a learning attitude and explore them.

Finally, the study compared the differences between spring and autumn activities in Satoyama using the landscape image sketching technique (LIST). The results showed that spring was perceived as being more abundant, beautiful, and full of vitality, while autumn activities were focused on transforming Satoyama to make it more widely used.

In conclusion, the study highlights the physical and mental health benefits of par-ticipating in Satoyama activities for older adult volunteers, regardless of the season. It also emphasizes the unique experiences and perspectives of older adult volunteers and young individuals and the importance of repeated exposure to Satoyama to fully appreciate its benefits. Additionally, the study suggests the potential for using Satoyama as a space for transforming and improving the natural environment.

Author Contributions: For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used –Con-ceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.l Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Mr. Yuan and Ms. Mao provided valuable assistance throughout the experiment. They were responsible for taking pictures and testing the participants' data, and Mr. Yuan specifically recorded the environmental physical indicators conditions. Additionally, they helped the author to organize the heart rate-related data and create the corresponding graphs and maps

Data Availability Statement: In this section, please provide details regarding where data sup-porting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Please refer to suggested Data Availability Statements in section –MDPI Research Data Policiesl at https://www.mdpi.com/ethics. If the study did not report any data, you might add –Not applicablel here.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Goulding MR, Rogers ME, & Smith SM. From the centers for disease control and prevention, public health and aging: trends in aging–United States and worldwide. Journal of the American Medical Association 289(2013): 1371-1373.

- Newgard C B, & Sharpless NE. Coming of age: molecular drivers of aging and therapeutic opportunities. The Journal of clinical investigation 123(2013): 946-950.

- Ageing and health. WHO 1(2022).

- Quadagno J. Aging and the life course: An introduction to social gerontology. McGraw-Hill Higher Education 10(2013).

- Hess BB, & Markson EW. Aging & old age: An introduction to social gerontology. New York: Macmillan 11(1980).

- Newgard CB, & Sharpless NE. Coming of age: molecular drivers of aging and therapeutic opportunities. J Clin Invest 123(2013): 946-950.

- Detoc M, Bruel S, Frappe P, et al. Intention to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial and to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in France during the Vaccine 38(2002): 7002-7006.

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC). National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Chronic Disease Notes and Reports: Special Focus. Healthy Aging 12(1999).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of self-reported arthritis or chronic joint symptoms among adults--United States, 2001. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report 51(2002): 948-

- Freedman V A, Martin LG & Schoeni RF. Recent trends in disability and functioning among older adults in the United States: a systematic review. Jama 288(2002): 3137-3146.

- Jacobzone S & Oxley Internationale Politik und Gesellschaft Online. Korea 5(2002): 0-2.

- Anderson GF, & Hussey Population Aging: A Comparison Among Industrialized Countries: Populations around the world are growing older, but the trends are not cause for despair. Health affairs 19(2000): 191-203.

- Levit K, Smith C, Cowan C, et Trends in US health care spending, 2001. Health Affairs 22(2003): 154-164.

- Cannon M What is aging? Dis 61(2015): 454-459.

- MA Musick J. Wilson, Volunteering and depression: the role of psychological and social resources in different age groups Sci. Med56 (2003): 259-269

- Ito Relationships between Motives for Participating in Volunteer Activities and Volunteer Activity Satisfaction, Benefits from Activities, and Life Satisfaction among the Elderly. Care and Behavioral Sciences of the Elderly 24(2019): 42-52

- Herzog A R, & House JS. Productive activities and aging well. Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging 15(1991): 49-54.

- Luoh M C, & Herzog AR. Individual consequences of volunteer and paid work in old age: Health and mortality. Journal of health and social behavior 10(2002): 490-509.

- Hunter MR, & Askarinejad Designer's approach for scene selection in tests of preference and restoration along a continuum of natural to manmade environments. Frontiers in psychology 6(2015): 1228.

- Miyazaki Y, Ikei H, & Song C. Forest medicine research in Japan. Nihon eiseigaku zasshi. Japanese journal of hygiene 69(2017): 122-135.

- Lee Forest and human health-recent trends in Japan. Forest medicine 10(2011): 243-257.

- Morimoto What is Satoyama? Points for discussion on its future direction. Landscape and Ecological Engineering 7(2011): 163-171.

- Nagano K, & Tabata A. Efforts for Conservation of Biodiversity in Satochi-satoyama and its Development in Japan and J. of Rural Planning Association 35 (2017): 465-468.

- Yoshioka A, Kadoya T, Imai J, et Overview of land-use patterns in the Japanese Archipelago using biodiversity-conscious land-use classifications and a Satoyama index. Japanese Journal of Conservation Ecology 18(2013): 141-156.

- Kagawa How to concern with Satoyama in future. Forest Science 42(2004): 46-50.

- Yokoyama K, Oku H, & Fukamachi K. A relationship between consciousness of landscape conservation, the attributes and the Satoyama conservation activities of the residents in urban fringe Satoyama area. JOURNAL OF RURAL PLANNING ASSOCIATION 23(2004): 91-96.

- Yoshino Urban residents_ consciousness toward Satoyama-Focusing on experience in nature play. - Environmental marketing 10(2015).

- Hansen MM, Jones R & Tocchini K. Shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) and nature therapy: A state-of-the-art review. International journal of environmental research and public health 14(2017):

- Park BJ, Tsunetsugu Y, Kasetani T, et al. Physiological effects of forest recreation in a young conifer forest in Hinokage Town, Japan. Silva Fenn 43(2011): 291-301.

- Lee J, Tsunetsugu Y, Takayama N, et al. Influence of forest therapy on cardiovascular relaxation in young adults. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine 10(2014).

- Song C, Joung D, Ikei H, et al. Physiological and psychological effects of walking on young males in urban parks in J. Physiol. Anthropol 32(2013): 18.

- Jung WH, Woo JM, & Ryu Effect of a forest therapy program and the forest environment on female workers_ stress. Urban forestry & urban greening 14(2015): 274-281.

- Song C, Ikei H, Kagawa T, et al. Physiological and psychological effects of viewing forests on young women. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 10(2019): 635.