Protocatechuic Acid Promotes Osteoblast Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Impact on Bone Metabolism, Osteoporosis and Fractures

Article Information

Lanny L. Johnson1*, Peter Chen2, Darryl D’Lima, PhD3

1President, Pcabioscience, LLC, 445 West 22nd Street, Holland, MI, USA

2Institute for Biomedical Sciences, San Diego, CA, USA

3Professor, Molecular & Cell Biology Scripps Research Institute, CA, USA

*Corresponding Author: Lanny L. Johnson, M.D., President, Pcabioscience, LLC, 445 West 22nd Street, Holland, MI, USA.

Received: 02 December 2025; Accepted: 08 December 2025; Published: 15 December 2025

Citation: Lanny L. Johnson, Peter Chen, Darryl D’Lima. Protocatechuic Acid Promotes Osteoblast Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Impact on Bone Metabolism, Osteoporosis and Fractures. Journal of Orthopedics and Sports Medicine. 7 (2025): 579-584.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Protocatechuic acid (PCA) is found throughout nature, common to the human diet and produced daily by the bacteria in human large bowel microbiome. PCA, a food supplement, is safe by any measure; non-toxic, non-allergenic and non-mutagenic. Our in vitro results revealed that PCA promotes osteoblast differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) cultures, as indicated by increased expression of SSP1, RUNX2, and ALPL and calcium deposition. These results may ultimately lead to the use of PCA, a nutraceutical, for the treatment of metabolic bone disorders, osteoporosis, and fractures.

Keywords

Mesenchymal stem cells; Osteoblasts; Protocatechuic acid; Osteoporosis; Osteopenia; Bone fracture

Article Details

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis is a common disorder among the elderly, many of whom develop decreased bone mass due to disorders in bone remodeling mechanisms [1,2]. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that in 2017-2018, 10 million people 50 years of age and older (and four to five times as many women as men) carried this diagnosis [3]. Recent estimates suggest that just over 47 million individuals will develop osteopenia (i.e., low bone mass), a condition that puts them at increased risk for ultimately developing osteoporosis [4].

Although lifestyle and dietary modifications may be useful in preventing osteoporosis [5], several specific treatments have recently become available [6]. Most of these agents are classified as anti-resorptive, and as a group, they target osteoclasts, which break down bone as part of the natural bone remodeling process. However, oral osteoporosis medications (including alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate, and zoledronic acid) can lead to variety of adverse effects, most notably bone, joint, and muscle pain, as well as nausea, difficulty swallowing, heartburn, irritation of the esophagus, and in some cases, gastric ulcer [7]. Similarly, although uncommon, osteonecrosis of the jaw has been recognized as among the most serious of the adverse effects of these medications [8]. Romosozumab is a dual action bone density drug that carries an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, and death from heart disease. [9]

There is clearly a need for safer and effective medicine for osteoporosis. Protocatechuic acid (PCA) is possible reagent. PCA has been used for centuries in traditional Chinese medicine for a variety of chronic conditions. [10]. PCA is found throughout nature. PCA is common to the human diet. PCA is product of the human large bowel microbiome. PCA is safe and nontoxic, nonallergenic, and non-mutagenic. The pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics are known [10].

Recent results revealed that PCA may also be an effective treatment for osteoporosis. Because primary osteoporosis in women results from excessive bone resorption due to estrogen insufficiency that occurs after menopause, most of the publications featuring PCA focus on its role in arresting osteoclast activity and preventing ongoing bone resorption [11-14]. However, we are particularly interested in recent reports that highlight PCA's impact on osteoblast development [15-17]. Collectively, the results of these latter studies suggest that osteoblast progenitors may be an effective target for the development of interventions that are effective against osteoporosis.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies that have examined the impact of PCA on human mesenchymal stem cells that emphasize its potential anabolic activity. Thus, this study aimed to explore the contributions of PCA to the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Positive results could broaden clinical applications of this agent beyond osteoporosis to include fracture healing, new bone formation, bone tissue engineering, and other aspects of regenerative medicine.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Cells and reagents

Primary human bone marrow-derived MSCs and their respective growth media were obtained from RoosterBio, Inc. (Frederick, MD, USA), American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), and Cell Applications (San Diego, CA, USA) and expanded in culture as per manufacturers’ instructions. Human osteoblasts (positive controls) were from Cell Applications. Crystalline PCA (3,4-dihydrobenzoic acid) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Stock solutions were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 648 mM and stored at -80 °C pending use. Alizarin red S was purchased from Pfaltz & Bauer (Waterbury, CT, USA, catalog no. 58005) and dissolved in distilled water to a stock concentration of 2 mg/mL, with pH adjusted with 1 M HCl to 4.1-4.3.

2.2 Tissue culture

Pre-characterized MSCs were expanded as described, transferred to 24-well plates at 104 cells/well, and cultured overnight before initiating the experiments. Triplicate wells were inoculated with PCA to final concentrations ranging from 200 µM to 2 mM, transferred to human osteoblast differentiation media (Cell Applications, catalog no. 417D-250) (positive control), or left untreated (negative control). Cultures were maintained for 14 to 21 days, with media changed twice each week. Each experiment was repeated three to four times.

2.3 RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

RNA was extracted from cultured cells on day 14 and day 21 using RNeasy kits (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). No obvious cytotoxicity was noted (i.e., floating or detached cells). cDNA was synthesized from 50 ng of RNA using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). Expression of osteogenic genes, including osteopontin (also known as secreted phosphoprotein-1, SPP1), RUNX family transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (ALPL), and bone sialoprotein (also known as integrin-binding sialoprotein, IBSP), was evaluated by reverse-transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) using pre-validated TaqMan® gene expression reagents (Applied Biosystems). GAPDH was used to normalize gene expression.

2.4 Alizarin red staining

Cells cultured for 21 days as described above were stained with Alizarin red.

2.5 Statistical evaluation

The qRT-PCR findings are presented as mean fold-change over gene expression levels in the negative control/untreated cells calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

3. Results

In the following experiments, we examined the expression of four osteoblast-associated genes (SSP1, RUNX2, ALPL, and BSP) and calcium deposition in human MSCs cultured for two to three weeks with PCA.

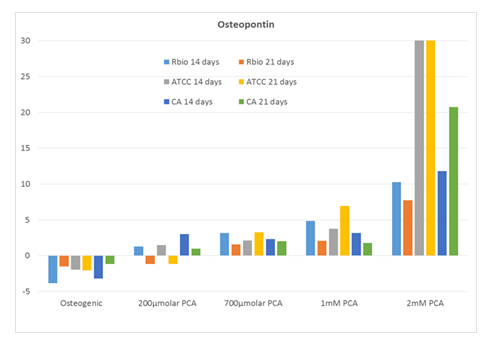

As shown in Figure 1, we observed a prominent dose-dependent increase in the expression of SSP1 (osteopontin), reaching levels of 8 – 30-fold over background in response to 2 mM PCA. Interestingly, SSP1 expression levels observed in response to PCA were higher than those detected in cultures maintained in commercial osteogenic medium alone.

Expression of SSP1 (fold over untreated [negative control]) in human MSCs from three distinct sources after 14 and 21 days in culture with increasing concentrations of PCA or commercial osteogenic medium (positive control). Abbreviations: RBio, Rooster Bio, Inc.; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; CA, Cell Applications; PCA, protocatechuic acid.

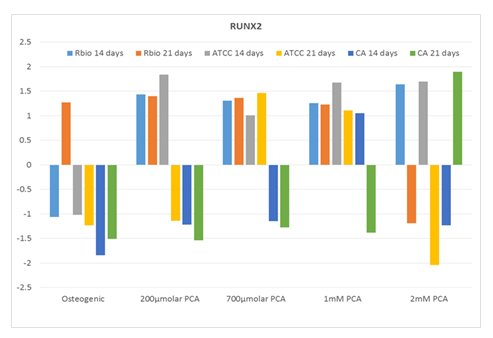

RUNX2 expression also increased in response to PCA, albeit somewhat less consistently (Figure 2). The human MSCs from ATCC responded the most consistently, with ~1.5-fold increases.

RUNX2 expression after 14 days in culture over the full range of PCA concentrations (2 µM to 2 mM).

Expression of RUNX2 (fold over untreated [negative] control) in human MSCs from three distinct sources after 14 and 21 days in culture with increasing concentrations of PCA or commercial osteogenic medium (positive control). Abbreviations: RBio, Rooster Bio, Inc.; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; CA, Cell Applications; PCA, protocatechuic acid.

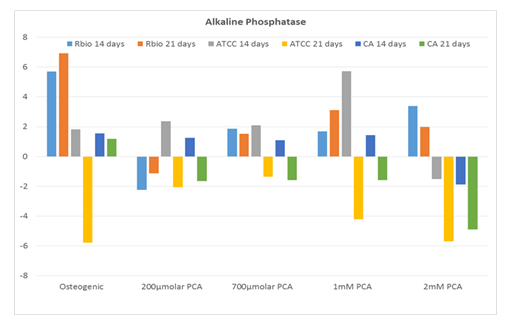

By contrast, ALPL (tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase) expression in response to PCA exhibited no dose-dependence and was overall similar to that observed in response to the commercial osteogenic medium (Figure 3).

Expression of ALPL (fold over untreated [negative] control) in human MSCs from three distinct sources after 14 and 21 days in culture with increasing concentrations of PCA or commercial osteogenic medium (positive control). Abbreviations: RBio, Rooster Bio, Inc.; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; CA, Cell Applications; PCA, protocatechuic acid.

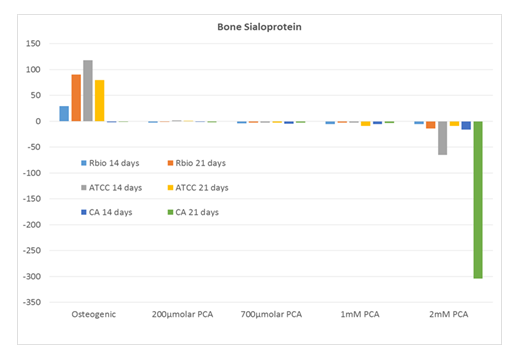

Interestingly, although IBSP was expressed prominently (~25-100-fold over untreated control) in human MSCs cultured in commercial osteogenic medium, a similar pattern was not observed in the PCA-treated cultures (Figure 4).

Expression of IBSP (fold over untreated [negative] control) in human MSCs from three distinct sources after 14 and 21 days in culture with increasing concentrations of PCA or commercial osteogenic medium (positive control). Abbreviations: RBio, Rooster Bio, Inc.; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; CA, Cell Applications; PCA, protocatechuic acid.

Calcium deposition was examined after three weeks in culture using an alizarin red assay. As shown in Figure 4, prominent calcium deposition (red color) over background levels was observed only in the human MSCs from ATCC that were cultured with the highest concentration (2 mM) of PCA.

4. Discussion

Although most treatments for osteoporosis focus on agents that inhibit osteoclast activity [6], we and others are interested in exploring a parallel anabolic role for PCA effect on human mesenchymal stem cells for this indication [15-18].

In this study, we examined the impact of PCA on gene expression and calcium deposition, specifically in human MSC cultures. We found that, overall, human MSCs responded positively to PCA with increased expression of three of four important osteogenic genes. Similarly, calcium deposition was observed in response to PCA in one of the three human MSC lines tested. As anticipated, we observed significant variability in the osteogenic responses of human MSCs from different commercial sources. One possible reason for these varied responses might be donor-to-donor variability. Alternatively, calcium deposition, which typically occurs later in the osteogenic timeline, might be more apparent after three weeks.

Our results revealed that human MSCs exhibited a prominent dose-dependent increase in the expression of SSP1 (osteopontin). Osteopontin is a key differentiation marker of the osteoblast lineage and is expressed in response to mechanical stress, inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and osteotropic hormones, including vitamin D3 and retinoic acid [19-22].

Human MSCs also expressed RUNX2 and ALPL (tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase) under these culture conditions. RUNX2 functions as a master regulator of bony matrix and chondrocyte genes, including mammalian Spp1 and Ibsp, among others [23,24]. Similarly, alkaline phosphatase is essential for the process of tissue mineralization, including calcium and phosphorus deposition in developing bones and teeth.

Interestingly, and despite high expression levels observed in cultures maintained in commercial osteogenic media (i.e., positive control), PCA did not promote the expression of IBSP (bone sialoprotein) in human MSC cultures. This is particularly intriguing, given that PCA induced the expression of RUNX2 under these conditions. However, at least one previous study suggested that other factors may be involved in this induction pathway [25].

Our study has several limitations. First, although we detect the prominent expression of several osteogenic genes, we have not yet documented protein expression and cell morphology. Likewise, although our findings suggest that PCA-treated human MSC cultures generate functional osteoblasts, calcium deposition was not evaluated quantitatively. These issues can be addressed in future studies.

Collectively, these findings add to the growing literature focused on alternative targets for osteoporosis therapy. Other agents under exploration that target osteoblast development for this application include bone marrow morphogenetic proteins, Wnt signaling regulators, and proteosome inhibitors, as well as other natural compounds [26-31]. Once validated and introduced into clinical practice, protocatechuic acid, a nutraceutical might be used as an alternative or even in conjunction with current osteoclast-targeting agents as much-needed anabolic treatments for osteoporosis as well as enhanced fracture healing, bone tissue engineering, and other aspects of regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgments

This study was entirely funded by Pcabioscience, LLC of Las Vegas, NV. Dr. Johnson is the owner. Dr. Johnson holds US patent 10,143,670 December 4, 2018, regarding fracture healing. The study was performed on an independent contract basis with Pcabioscience’s payment to the Institute for Biomedical Sciences, 3120 Biomedical Sciences Way, La Jolla, CA 92093. Drs. Chen and D’Lima were independent contractors functioning under work for hire status and who designed and executed this study without any financial interests. Drs. Chen and D’Lima have no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions:

Dr. Johnson proposed the hypothesis and wrote the manuscript. Drs. Chen and D’Lima designed, directed and or preformed the study. All authors have read and approved the final submitted manuscript.

References

- Zhivodernikov IV, Kirichenko TV, Markina YV, et al. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of osteoporosis. Int J Mol Sci 24 (2023): 15772.

- Porter JL, Varacallo MA. Osteoporosis. StatPearls (2023).

- Sarafrazi N, Wambogo EA, Shepherd JA. Osteoporosis or low bone mass in older adults: United States, 2017–2018. Natl Center Health Stat Data Brief 405 (2021).

- Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States. J Bone Miner Res 29 (2014): 2520-2526.

- Christianson MS, Shen W. Osteoporosis prevention and management. Clin Obstet Gynecol 56 (2013): 703-710.

- Chen Y-J, Jia L-H, Han T-H, et al. Osteoporosis treatment: current drugs and future developments. Front Pharmacol 15 (2024).

- Kennel KA, Drake MT. Adverse effects of bisphosphonates: implications for osteoporosis management. Mayo Clin Proc 84 (2009): 632-638.

- Gupta M, Gupta N. Bisphosphonate-related jaw osteonecrosis. StatPearls (2023).

- Krupa KN, Parmar M, Delo LF. Romosozumab. StatPearls (2025).

- Song J, He Y, Luo C, et al. New progress in the pharmacology of protocatechuic acid. Pharmacol Res 161 (2020): 105109.

- Jang S-A, Song HS, Kwon JE, et al. Protocatechuic acid attenuates trabecular bone loss in ovariectomized mice. Oxid Med Cell Longev (2018): 7280342.

- Qu Z, Zhao S, Zhang Y, et al. Natural compounds for bone remodeling. Biomed Pharmacother 180 (2024): 117490.

- Wu Y-X, Wu T-Y, Xu B-B, et al. Protocatechuic acid inhibits osteoclast differentiation and stimulates apoptosis. Biomed Pharmacother 82 (2016): 399-405.

- Jang SA, Song HS, Kwon JE, et al. Protocatechuic acid attenuates trabecular bone loss in ovariectomized mice. Oxid Med Cell Longev (2018): 7280342.

- Rivera-Piza A, An YJ, Kim DK, et al. Protocatechuic acid enhances osteogenesis but inhibits adipogenesis. J Med Food 20 (2017): 309-319.

- Xu G, Pei QY, Ju CG, et al. Detection on effect of different processed Cibotium barometz on osteoblasts. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 38 (2013): 4319-4323.

- Feng X, Feng W, Wu P, et al. Mechanism of protocatechuic acid in treating osteoporosis via HIF-1 pathway. J Funct Foods 122 (2024): 106531.

- Beaudart C, Veronese N, Douxfils J, et al. PTH1 receptor agonists for fracture risk. Osteoporos Int (2025).

- Zhu S, Chen W, Masson A, et al. Cell signaling and transcriptional regulation of osteoblast lineage commitment. Cell Discov 10 (2024).

- Zohar R, Cheifetz S, McCulloch CAG, et al. Intracellular osteopontin as a marker of osteoblastic differentiation. Eur J Oral Sci 106 (1998): 401-407.

- Mardiyantoro F, Chiba N, Seong C-H, et al. Two-sided function of osteopontin during osteoblast differentiation. J Biochem (2024).

- Sodek J, Chen J, Nagata T, et al. Regulation of osteopontin expression in osteoblasts. Ann N Y Acad Sci 760 (1995): 223-241.

- Komori T. Roles of RUNX2 in skeletal development. Adv Exp Med Biol (2017): 83-93.

- Jonason JH, Xiao G, Zhang M, et al. Post-translational regulation of RUNX2 in bone and cartilage. J Dent Res 88 (2009): 693-703.

- Artigas N, Ureña C, Rodríguez-Carballo E, et al. MAPK-regulated interactions between Osterix and Runx2. J Biol Chem 289 (2014): 27105-27117.

- Kanakaris NK, Petsatodis G, Tagil M, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins in osteoporotic fractures. Injury 40 (2009): S21-S26.

- Manolagas SC. Wnt signaling and osteoporosis. Maturitas 78 (2014): 233-237.

- Canalis E. Wnt signalling in osteoporosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 9 (2013): 575-583.

- Garrett IR, Chen D, Gutierrez G, et al. Proteasome inhibitors stimulate bone formation. J Clin Invest 111 (2003): 1771-1782.

- An J, Yang H, Zhang Q, et al. Natural products for treatment of osteoporosis. Life Sci 147 (2016): 46-58.

- Yang Y, Jiang Y, Qian D, et al. Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis with natural products. J Orthop Surg Res 18 (2023).