Portal Vein Pulsatility, A Better Indicator of Volume Status in COVID-19?

Article Information

Filipe Gonzalez1*, Duarte Martins2, Jacobo Bacariza1, Rui Gomes1, Antero Fernandes1

1Department of Intensive Care, Hospital Garcia de Orta, Almada, Portugal

2Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Hospital de Santa Cruz, Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Ocidental, Lisboa, Portugal

*Corresponding author: Filipe Gonzalez, Department of Intensive Care, Hospital Garcia de Orta, Avenida Torrado da Silva, 2805-267 Almada, Portugal

Received: 20 September 2020; Accepted: 28 September 2020; Published: 20 November 2020

Citation: Filipe Gonzalez, Duarte Martins, Jacobo Bacariza, Rui Gomes, Antero Fernandes. Portal Vein Pulsatility, A Better Indicator of Volume Status in COVID-19?. Cardiology and Cardiovascular Medicine 4 (2020): 715-717.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookKeywords

Acute kidney injury; COVID-19

Article Details

Abbreviations:

AKI: Acute kidney injury; RRT: Renal replacement therapy; VEXUS score: Venous EXcess UltraSound; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; US: Ultrasound; IVC: Inferior vena cava; PVP: Portal vein pulsatility; NT-proBNP: N-terminal-pro hormone B-type Natriuretic Peptide

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is common among critically ill patients with COVID-19, affecting approximately 20–40% of patients admitted to intensive, of whom 20% require renal replacement therapy (RRT) [1,2]. Little is known about the cardiovascular consequences of COVID-19 of patients requiring ICU admission. Still, hemodynamic management plays an important role, as the need for vasopressor support in 95% of mechanically ventilated patients was reported in NEJM [3]. Recently, the VEXUS score (Venous EXcess UltraSound) has gained some visibility as a congestion score combining multiple ultrasound markers to evaluate systemic venous congestion [4].

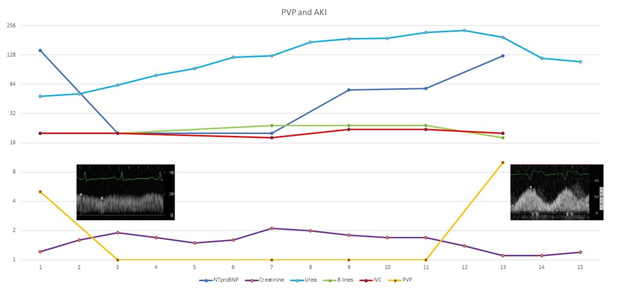

In our Intensive Care Unit (ICU), we evaluated the first seven patients with COVID-19, with particular focus on ultrasound (US) evaluation, including lung, heart, inferior vena cava (IVC), and portal vein. All of them were mechanically ventilated; five were men, five had AKI, of which one needed RRT, and none died. Figure 1 is a representative graph showing a median of the seven patients for each of the variables displayed (in the y-axis) throughout the time (days on the x-axis). A quick and straightforward interpretation of this graph: as patients get hypovolemic with furosemide, creatinine and urea increases, and portal vein pulsatility (PVP) and N-terminal (NT)-pro hormone B-type Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP) decreases; IVC variation and B-lines in lung US don’t change significantly.

Also, we followed this seven patients for seven days and fit a linear mixed-effects model fit by maximum likelihood with normalized creatinine as the outcome variable, with fixed effects of PVP, time and NT-proBNP and random slopes for PVP, time and NT-proBNP (B-lines was not fitted in this model, as there was no correlation in the primary analysis). We found that for each 10% increase in PVP we estimate an increase of 0.5 mg/dL in creatinine ( β-coefficient -0.054, SD 0.017, p=0.0044), as opposed to the non-significant effect of IVC variation (β-coefficient -0.15, SD 0.137, p=0.287) and the marginal effect of NT-proBNP (β-coefficient 0.0016, SD 0.0006, p=0.095).

As lung disease progresses towards more severe forms like ARDS, the pressure to stay dry can lead to a hypovolemic status, worsening further AKI. Some indirect measures, like IVC variation and the number of B-lines, can help define and guide volume status. But maybe these measurements are not the best on COVID-19 patients, as IVC dilatation and lack of variability can result from the parenchymal and vascular lung involvement and superimposed high pressures from aggressive mechanical ventilation, and B lines can solely represent interstitial viral inflammation, more than fluid overload. Although this is a small number of patients, PVP could be a better conceptual marker of the volume status in COVID-19 patients.

Figure 1: A representative pulsed-wave doppler of the portal vein can be seen at the beginning with a monophasic flow, indicating non-hypervolemia (possible hypo- to normovolemia), and at the end with a biphasic flow, indicating venous congestion (possible hypervolemia). PVP: Portal Vein Pulsatility; AKI: Acute Kidney Injury; NTproBNP: NT terminal of the pro-brain natriuretic peptide; IVC: Inferior Vena Cava variation.

References

- Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes among 5700 Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc (2020).

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet (2020).

- Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, Schenck EJ, Chen R, Jabri A, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med (2020).

- Beaubien-Souligny W, Rola P, Haycock K, Bouchard J, Lamarche Y, Spiegel R, et al. Quantifying systemic congestion with Point-Of-Care ultrasound: development of the venous excess ultrasound grading system. Ultrasound J (2020).