Pediatric Patient with Sleep Disordered Breathing (Sdb) of Central Origin Secondary to Arnold Chiari Type I Malformation: A Case Report

Article Information

Diego Morena Valles1*, Sofía Romero Peralta1, Olga Mediano1, 2, 3

1Department of Pulmonology, Guadalajara University Hospital, Guadalajara, Spain

2Department of Medicine, University of Alcalá de Henares, Alcalá de Henares, 28871 Madrid, Spain

3Center for Biomedical Research in Respiratory Diseases Network (CIBERES), 28029 Madrid, Spain

*Corresponding Author: Diego Morena Valles MD, Department of Pulmonology, Guadalajara University Hospital, Guadalajara, Spain

Received: 18 Febraury 2021; Accepted: 26 Febraury 2021; Published: 03 March 2021

Citation: Diego Morena Valles, Sofía Romero Peralta, Olga Mediano. Pediatric patient with Sleep Disordered Breathing (SDB) of central origin secondary to Arnold Chiari type I malformation: a case report. Journal of Surgery and Research 4 (2021): 80-84.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

The diagnosis and treatment of Sleep Disordered Breathing (SDB) in pediatric age differs in relation to the adult. Central sleep apnea syndrome (CSAS) is less frequent in childhood, and one of the causes of it is the alterations of the brainstem like the malformation of Chiari type I. The main diagnostic method of SDB is Polysomnography, and there are other methods like brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to investigate its etiology. Here, we share our experience with an 8-year-old female with malformation of Chiari type I and CSAS, and the steps we followed for the diagnosis and successful treatment of such an infrequent pathology in childhood.

Keywords

Sleep Disordered Breathing; Central sleep apnea syndrome; Malformation of Chiari type I; Brain MRI and children

Sleep Disordered Breathing articles; Central sleep apnea syndrome articles; Malformation of Chiari type I articles; Brain MRI and children articles

Sleep Disordered Breathing articles Sleep Disordered Breathing Research articles Sleep Disordered Breathing review articles Sleep Disordered Breathing PubMed articles Sleep Disordered Breathing PubMed Central articles Sleep Disordered Breathing 2023 articles Sleep Disordered Breathing 2024 articles Sleep Disordered Breathing Scopus articles Sleep Disordered Breathing impact factor journals Sleep Disordered Breathing Scopus journals Sleep Disordered Breathing PubMed journals Sleep Disordered Breathing medical journals Sleep Disordered Breathing free journals Sleep Disordered Breathing best journals Sleep Disordered Breathing top journals Sleep Disordered Breathing free medical journals Sleep Disordered Breathing famous journals Sleep Disordered Breathing Google Scholar indexed journals Central sleep apnea syndrome articles Central sleep apnea syndrome Research articles Central sleep apnea syndrome review articles Central sleep apnea syndrome PubMed articles Central sleep apnea syndrome PubMed Central articles Central sleep apnea syndrome 2023 articles Central sleep apnea syndrome 2024 articles Central sleep apnea syndrome Scopus articles Central sleep apnea syndrome impact factor journals Central sleep apnea syndrome Scopus journals Central sleep apnea syndrome PubMed journals Central sleep apnea syndrome medical journals Central sleep apnea syndrome free journals Central sleep apnea syndrome best journals Central sleep apnea syndrome top journals Central sleep apnea syndrome free medical journals Central sleep apnea syndrome famous journals Central sleep apnea syndrome Google Scholar indexed journals Malformation of Chiari type I articles Malformation of Chiari type I Research articles Malformation of Chiari type I review articles Malformation of Chiari type I PubMed articles Malformation of Chiari type I PubMed Central articles Malformation of Chiari type I 2023 articles Malformation of Chiari type I 2024 articles Malformation of Chiari type I Scopus articles Malformation of Chiari type I impact factor journals Malformation of Chiari type I Scopus journals Malformation of Chiari type I PubMed journals Malformation of Chiari type I medical journals Malformation of Chiari type I free journals Malformation of Chiari type I best journals Malformation of Chiari type I top journals Malformation of Chiari type I free medical journals Malformation of Chiari type I famous journals Malformation of Chiari type I Google Scholar indexed journals Brain MRI in children articles Brain MRI in children Research articles Brain MRI in children review articles Brain MRI in children PubMed articles Brain MRI in children PubMed Central articles Brain MRI in children 2023 articles Brain MRI in children 2024 articles Brain MRI in children Scopus articles Brain MRI in children impact factor journals Brain MRI in children Scopus journals Brain MRI in children PubMed journals Brain MRI in children medical journals Brain MRI in children free journals Brain MRI in children best journals Brain MRI in children top journals Brain MRI in children free medical journals Brain MRI in children famous journals Brain MRI in children Google Scholar indexed journals Polysomnography articles Polysomnography Research articles Polysomnography review articles Polysomnography PubMed articles Polysomnography PubMed Central articles Polysomnography 2023 articles Polysomnography 2024 articles Polysomnography Scopus articles Polysomnography impact factor journals Polysomnography Scopus journals Polysomnography PubMed journals Polysomnography medical journals Polysomnography free journals Polysomnography best journals Polysomnography top journals Polysomnography free medical journals Polysomnography famous journals Polysomnography Google Scholar indexed journals Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome articles Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome Research articles Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome review articles Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome PubMed articles Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome PubMed Central articles Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome 2023 articles Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome 2024 articles Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome Scopus articles Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome impact factor journals Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome Scopus journals Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome PubMed journals Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome medical journals Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome free journals Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome best journals Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome top journals Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome free medical journals Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome famous journals Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome Google Scholar indexed journals sleep architecture articles sleep architecture Research articles sleep architecture review articles sleep architecture PubMed articles sleep architecture PubMed Central articles sleep architecture 2023 articles sleep architecture 2024 articles sleep architecture Scopus articles sleep architecture impact factor journals sleep architecture Scopus journals sleep architecture PubMed journals sleep architecture medical journals sleep architecture free journals sleep architecture best journals sleep architecture top journals sleep architecture free medical journals sleep architecture famous journals sleep architecture Google Scholar indexed journals superficial sleep articles superficial sleep Research articles superficial sleep review articles superficial sleep PubMed articles superficial sleep PubMed Central articles superficial sleep 2023 articles superficial sleep 2024 articles superficial sleep Scopus articles superficial sleep impact factor journals superficial sleep Scopus journals superficial sleep PubMed journals superficial sleep medical journals superficial sleep free journals superficial sleep best journals superficial sleep top journals superficial sleep free medical journals superficial sleep famous journals superficial sleep Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

Introduction

The prevalence of Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) in children under 5 years of age is around 3%, with a peak incidence between the ages of 2 and 5 [1], being much less frequent in the case of central sleep apnea syndrome (CSAS).

Combinations of anatomical and functional factors influence the pathogenesis of childhood OSA. Among the causes of CSAS, diseases of the central nervous system, alterations of the brainstem (tumors, malformation of Chiari type I and type II, stenosis of the foramen magno) and the use of sedative or narcotic medication stand out [1-3].

The current diagnostic reference method for any SDB in children is Polysomnography (PSG), although Cardiorespiratory Polygraphy (CRP) could also be performed if necessary as a first diagnostic approach if the symptomatology is highly suggestive. Other diagnostic methods are also useful for discovering the etiology of SDB such as brain MRI [4].

The treatment of OSA in children is mainly based on the etiology of the disease. In the case of CSAS, the treatment of choice is that of the underlying pathology, so its identification is essential [3-5].

Here, we describe a childhood patient with a diagnosis of moderate mixed OSA of central predominance. The etiology of this disease, Arnold Chiari Type I syndrome, was discovered by performing a brain MRI. This case provides a bibliography on how to act and what steps to follow when diagnosing a CSAS in childhood.

Report of case

We report the case of an 8-year-old girl, native from Spain, with no personal history of interest. She has a family history of a mother with a diagnosis of severe OSA in treatment with nocturnal CPAP, a 14- year- old sister with a diagnosis of severe OSA, and in treatment with nocturnal CPAP and an 11- year- old brother with a diagnosis of moderate OSA.

The patient was referred to the Guadalajara University Hospital´s Sleep Unit for restless sleep symptoms, apnea witnessed accompanied by persistent snoring, headache and bruxism. She did not refer to nocturnal enuresis, and had a good school performance. Physical examination highlights tonsillar hypertrophy III/IV with normal palate and cardiopulmonary auscultation without alterations. In December 2017, when the patient was 6 years old, hospital CRP was performed with a result of severe OSA with obstructive predominance (apneas hypopnea index-AHI 16/h; obstructive apnea index-OAI: 15.3/h; central apnea index-CAI: 0.7/h). Tonsilectomy was decided, after which the patient showed clinical improvement with decreased daytime hypersomnolence, but persistence of the other symptoms, with headache predominance.

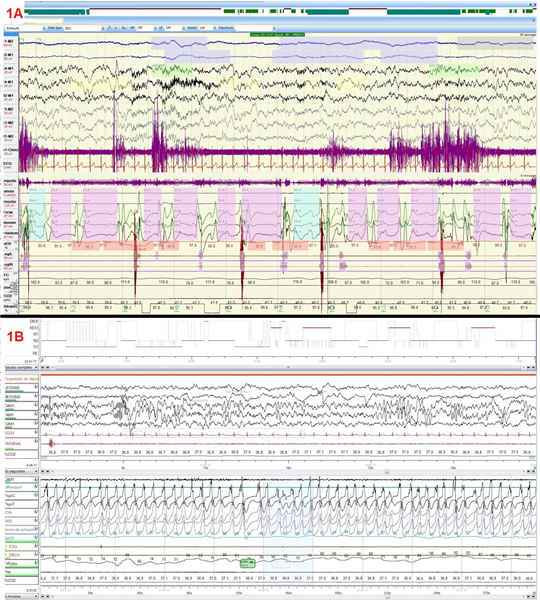

In October 2018, according to the hospital protocol, CRP was performed after surgery, with a diagnosis of moderate mixed OSA with central predominance (AHI: 9.3/h: OAI: 3.3/h; CAI 6/h). Otolaryngology endoscopy evaluation showed small non-obstructive adenoid remains. Following the Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) recommendations in hospital PSG (Grael Ergometrix ©) was performed. The manual analysis showed sleep architecture alterations with increased superficial sleep and frequent awakenings during sleep. Very frequent respiratory events (AHI: 26.7/h, OAI: 8.4/h, CAI: 18.3/h), accompanied by significant and long-lasting desaturations were recorded (Image 1A, 1B).

Image 1A: Pre-surgery PSG where multiple apneas of central origin are visible.

Image 1B: Post-surgery PSG where central apneas were resolved.

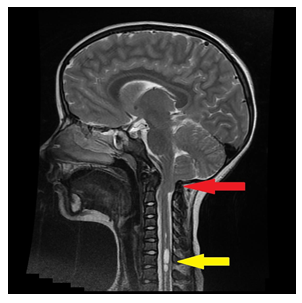

Given this diagnosis, an etiological study of the CSAS was initiated, performing cerebral- cervical-dorsal contrast MRI. A 9 mm descent of the cerebellar tonsils was observed below the plane of the great hole compatible with Arnold Chiari type I malformation, in association to cervical syringomyelia that extended from C5 to D9 (Image 2).

Image 2: MRI of T2 sagittal brain showing a 9 mm decrease in cerebellar tonsils below the plane of the great hole compatible with Arnold Chiari type I malformation (red arrow), in association to cervical syringomyelia that extends from C5 until D9 (yellow arrow).

In July 2020, the patient undergoes decompressive neurosurgery without relevant complications. PSG was repeated 3 months after surgery demonstrating good sleep efficiency and no central respiratory events (Image 1B) and symptoms improvement.

Discussion

SDB in pediatric age differs in the definition, diagnosis, and treatment in relation to the adult. The child shows anatomical and functional peculiarities in the airway along with maturational characteristics from the point of view of sleep neurophysiology [2].

Tonsillar hypertrophy is the main nasal and oropharyngeal anatomical pathogenesis factor of childhood OSA. Less frequent factors are obesity, dental malocclusion or craniofacial malformations [2].

The most frequent clinical manifestations of OSA are snoring, evidence of nocturnal apnea, daytime hyperactivity or hypersomnolence, poor school performance and neurocognitive alterations1. In the case of CSAS usually occur asymptomatically.

CSA is relatively rare in healthy children. When it does occur, it is usually in the context of an underlying medical condition or neuroanatomical abnormalities. A CAI >5/hr is a reasonable threshold to define clinically significant CSA. Because children may be asymptomatic, those at high risk for CSA should be screened [6]. In healthy children with a PSG diagnosis of CSA we suggest MRI evaluation to assess neuroanatomical abnormalities.

A brain MRI may be an important diagnostic tool for unexplained sleep central apnea in children [4]. In our case, the performance of a brain MRI showed the cause of the pathology. The malformation of Chiari type I is characterized by the existence of a decrease in the cerebellar tonsils that are located below the foramen magnum, associated with compressive phenomena of the brainstem and upper spinal cord. According to the description of Ferré et al [2], the most frequent clinical manifestations are usually occipitonucal headaches, dizziness, and nocturnal respiratory disturbances, such as central apneas.

Adeno-tonsillectomy is the most frequent technique of treatment in children´s OSA, with an improvement in AHI of 75% [1]. Other non-surgical treatments would be the use of CPAP, weight loss, maxillary expansion and/or orthodontics and other methods aimed at eliminating the possible etiological trigger [1]. In the case of CSAS, it is important to identify the underlying pathology. For Arnold Chiari malformation, it is usually decompressive neurosurgery [5].

After surgery, our patient improved all the symptoms related to this pathology and the respiratory events´ disappearance was confirmed in the PSG.

In summary, the Arnold Chiari malformation is a rare cause of central apneas in the pediatric patient, which requires an MRI study for diagnosis. It is important to assess these possible causes in a case of pediatric CSA. We also consider that it would be useful to carry out studies in Chiari malformation´s patients to evaluate respiratory alterations before and after surgery to determine whether surgery treats SDB.

Abbreviations

AHI Apneas hypopnea index

CAI Central apnea index

CRP Cardiorespiratory Polygraphy

CSAS Central sleep apnea syndrome

MRI Magnetic resonance imaging

OAI Obstructive apnea index

OSA Obstructive Sleep Apnea

PSG Polysomnography

SEPAR Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery

SDB Sleep Disordered Breathing

References

- Leu Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders and the Chiari 1 Malformation. Chest 148 (2015):1346-1352.

- Ferré Á, Poca MA, De la Calzada, Moncho D, Romero O, Sampol G, et al. Sleep Related Breathing Disorders in Chiari Malformation Type 1: A Study of 90 Patients. Sleep 40 (2017): 98-109.

- Zaffanello M, Sala F, Sacchetto L, Gasperi E, Piacentini Evaluation of the central sleep apnea in asymptomatic children with Chiari 1 malformation: an open question. Childs Nerv Syst 33 (2017): 829-832.

- Selvadurai S, Al-Saleh S, Amin R, Zweerink A, Drake J, Propst EJ, et al. Utility of brain MRI in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Laryngoscope 127 (2017): 513-519.

- Botelho RV, Bittencourt LR, Rotta JM, Tufik The effects of posterior fossa decompressive surgery in adult patients with Chiari malformation and sleep apnea. J Neurosurg. 112 (2010): 800-807.

- L. Alonso-Álvarez et al / Arch Bronconeumol 47 (2011): 2-18