Non-Invasive Acoustic Myography for Measurement of Rumen Contractions

Article Information

Søndergaard Nissen RJ, Harrison AP*

University of Copenhagen, PAS, Section for Physiology, Dept for Veterinary and Animal Sciences (IVH), Faculty of Health & Medical Sciences, Dyrlægevej 100, 1870 Frederiksberg C, Denmark

*Corresponding author: Adrian Paul Harrison, University of Copenhagen, PAS, Section for Physiology, Dept for Veterinary and Animal Sciences (IVH), Faculty of Health & Medical Sciences, Dyrlægevej 100, 1870 Frederiksberg C, Denmark.

Received: 09 December 2025; Accepted: 12 December 2025; Published: 22 December 2025

Citation: Søndergaard Nissen RJ, Harrison AP. Non-Invasive Acoustic Myography for Measurement of Rumen Contractions. Journal of Nanotechnology Research. 7 (2025): 34-39.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

This study used a wireless acoustic myography device (SOFi M2 unit) that recorded high-quality rumen sound waves from cows in real time in a transdermal non-invasive fashion. Recordings reveal both extraneous and intrinsic sounds related to bolus movement in the oesophagus, m.Cutaneous trunci contractions in response to flies, contractions of the reticulum as well as contractions from the dorsal and ventral sacs. Details such as the timing of events in the rumen in relation to bolus movement in the oesophagus are presented as are gas bubble sounds from the paralumbar fossa as gas is displaced from the ventral blind sac at the end of an A-wave sequence. These detailed recordings will be of interest for students of veterinary medicine, and fully qualified veterinarians alike as an educational and diagnostic tool in connection with rumen motility.

Keywords

Rumen; Dorsal sac; Ventral sac; Reticulum; Oesophagus; Borborygmi

Article Details

Introduction

In a recent publication, it was shown that acoustic myography recordings, made through the hair and skin of cattle could detect rumen sounds, the result of rumen activity and metabolism [1]. However, whilst the publication by Vargas-Bello-Pérez and colleagues showed that such recordings were feasible, they did not address much of the details associated with rumination. Such technological solutions as non-invasive sensors become crucial in ruminant production, as they can measure rumen activity in real-time and warn of health risks before they become visible by affecting the level of productivity [1]. Indeed, such recordings have the potential to revolutionize agriculture by offering real-time data, which can help farmers and veterinarians improve precision farming and optimize feeding strategies [2, 3], especially at a time when feeds and CH4 emissions from ruminants are frequently discussed [4]. The health of dairy cows is closely linked to their digestive system, especially the function of the rumen. The dorsal and ventral sacs are the largest compartments of the ruminants' gastric chambers and they host a complex microbiota that plays a crucial role in the breakdown of cellulose and hemicellulose from plant-based foods. Such fermentation results in the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that are an important source of energy for the ruminants [5].

The market economy plays an important role in the decision-making process for farmers, especially in relation to feed prices and availability. Changes in global market prices for feed such as maize, cereals and soya may lead farmers to choose cheaper feed products or change rations to ensure economic profitability. However, these measures can compromise the health of ruminants if the cheaper alternatives do not meet nutritional requirements, or sudden changes in rumen microbiota populations occur as a result of a sudden change in feed, underlining the need for more precise tools to monitor and ensure the health of ruminants despite changing feeding strategies [4, 6].

In this context, there is increasing interest in the use of precision farming technology that enables monitoring of dairy cows' digestion and overall health. By being able to collect data on production animals, farmers and veterinarians could gain valuable insights into how changes in feeding, housing, etc., can affect the health of cows, and quickly adapt strategies to maintain optimal health and maintain production [1].

This study has therefore sought to examine the sounds made by regions of the rumen and oesophagus (borborygmi), to present them in detail and to examine the overall sequence of events as well their timing.

Material and Methods

Ethics: The Technology Used Was Entirely Non-Invasive And Animals Used In This Study Were Included In A License Approved by the Department of Veterinary and Animal Sciences from the University of Copenhagen (Protocol Id 2018-15-0201-01462).

Cows: Adult cows were sourced from the Large Animal Teaching Hospital (Taastrup), University of Copenhagen. These animals were not pregnant and had never been so, and were therefore fed a maintenance diet based on ad libitum meadow haylage (50%) and straw (50%) with 3 kg of concentrate per day. Other measurements were made from adult Red Danish cows at Assendrup Hovedgård (Haslev, Denmark) and were fed a total mixed ration ad libitum based on maize and grass silages supplemented by concentrate from milking robots (Lely, Maassluis, the Netherlands) according to their daily milk yield.

Rumen sounds: The sound recordings were made using SOFi M2 acoustic myography units (Advanced Myographic Technologies LLC, Ocala, FL, USA) at typical gain settings of 27-32 dB. Sound recordings lasted for approx. 20 min for each animal and were performed 2 hours after morning feeding. Recordings were performed in an open space under on-farm conditions. The recording site was prepared with acoustic gel (AMT LLC) which was thoroughly rubbed into the overlying hair to ensure a good connection with the skin above the site of interest. For the dorsal sac of the rumen a sensor was placed on the left side of the animal in between the last rib, paralumbar fossa, and the lumbar vertebrae (see Figure 1). For placement of sensors above the dorsal and ventral sac regions and the oesophagus see (Figure 1). Placement of the sensor for recordings from the reticulum was at the level of between the 7th and 8th rib (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: A schematic (Upper panel) showing the placement of the AMG sensors on the left side of the cows measured in this study. Each recording unit (SOFi; Advanced Myographic Technologies LLC, Ocala, FL, USA) weighed 10g and was wirelessly connected via Bluetooth to a smart phone for real-time monitoring of the signals. A photo (Lower panel) of the SOFi units in place on a cow whilst recording and secured in place using a flexible adhesive bandage (Snögg Industry AS, Kristiansand, Norway, now Norgesplaster AS).

Sensors (piezo ceramic - diameter of 50 mm; Advanced Myographic Technologies LLC, Ocala, FL, USA) were likewise prepared with acoustic gel, before they were attached to the site of interest using flexible self-adhesive bandage (Animal Polster, Snögg Industry AS, Kristiansand, Norway, now Norgesplaster AS) (Figure 3). The sensors were then connected to the SOFi M2 units and recordings were made in the form of a WAV file to a recording device via a wireless connection (Figure 3), so that the recordings could be monitored in real-time. Data collection used a sampling frequency of 1000 Hz. The SOFi M2 units weigh 10.2g and have a Bluetooth 4 connection to both tablet/smartphone supported software. The range on the Bluetooth connection has been measured to be approx. 80 meters, but through a remote link it is also possible to place a SOFi M2 unit on a cow, record rumen sounds at a distance of many km´s and transmit them to a Client Cloud where they can be accessed from anywhere around the World.

Analysis: The raw WAV file recordings were analyzed using the SOFi M2 software (https://myographytech.com/) and WavePad (WavePad Master Edition version 10.89 – NCH Software - https://www.nch.com.au/wavepad/index.html; Greenwood Village CO, 80111, USA). No filtering or processing of the data was made, but the recorded signal was monitored in real-time at the time of recording to make sure that sensor placement, gain setting etc were optimal.

Results

Sounds Extraneous to the rumen: The technology used in this study picked up sounds that were not strictly related to rumen fermentation and activity. These included sounds from the sensor placed above the reticulum in connection with a m. Cutaneous trunci reflex whenever a fly landed on the animals being measured. These signals were generally of a short duration (typically 0.6-0.8 sec in a cluster lasting up to 5-6 seconds). They were very easy to detect as they were visible and with real-time monitoring of the recorded signal it was possible to take a screen-shot and note the exact time they occurred.

Other recorded sounds extraneous to the rumen itself included those taken from the oesophagus. With a sensor placed above the oesophagus on the neck of the animals it was possible to detect bolus movement. Skeletal muscle activity in the wall of the oesophagus produced an audible signal every time a bolus of food passed the sensor. In animals that were ruminating, these signals were found to have an inter-bolus time of 3.5-5.0 seconds duration (see Figure 3), measured as the time between a bolus returning from the mouth to the rumen and a new bolus of forage being trafficked back up to the mouth.

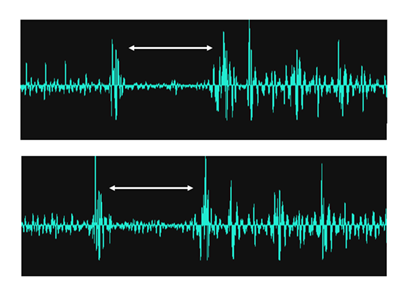

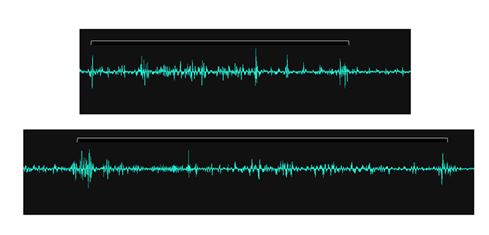

Figure 3: A couple of typical AMG signals recorded through the skin without having to shave the recording site, from a sensor placed on the neck above the oesophagus. The recorded sound sequence starts with a contraction of the muscle wall of the oesophagus as a food bolus travels from the mouth to the rumen, after which there is a quiet phase of 3.5-5.0 seconds duration, followed by a new food bolus trafficked this time from the rumen to the mouth, and a sequence of subsequent deglutitions. White brackets indicate the inter-bolus period and are flanked by skeletal muscle activity from the wall of the oesophagus.

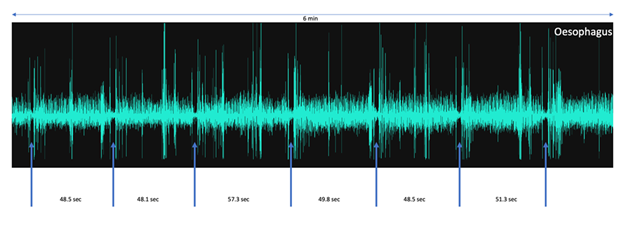

Figure 4: An overview of AMG signals recorded through the skin without having to shave the recording site, from sensors placed on the neck above the oesophagus. The blue arrows denote inter-bolus periods interspersed by periods of rumination with associated deglutitions. Note the timing of events for periods of rumination is relatively consistent. Total recording time 6.0 minutes.

Examining the recordings from the oesophagus sensor over a longer period of time it was also possible to measure rumination time, that is to say the period of time spent chewing a new bolus of forage before it was re-swallowed. In the present study this was found to last between 48 and 57 seconds (see Figure 4).

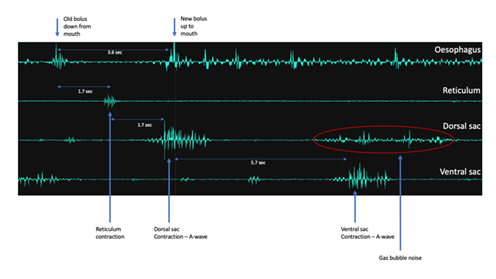

Sounds Intrinsic to the rumen: With the aid of the sensors placed above the dorsal and ventral sac of the rumen, the sensor above the reticulum and then in combination with signals from the oesophagus, it was possible to record a complete sequence of events from the ruminants in the present study (see Figure 5). The sequence of events in this case was taken to start with a chewed bolus of forage descending from the mouth via the oesophagus to the rumen (upper most trace), a contraction of the reticulum (second trace from the top) then followed and this was followed by the passage of a new bolus being trafficked to the mouth via the oesophagus. There then followed an A-sequence wave (mixing; third trace from the top) that spread across the dorsal sac and then later spread into the ventral sac (bottom trace). This wave of contraction resulted in the displacement of the waste products of microbial fermentation (rumen gasses; CH4, CO2, N2, H2, H2S) which percolated upwards from the ventral blind sac towards the sensor above the dorsal sac, and were captured as gas bubble sounds.

Figure 5: An overview four channel AMG recording through the skin without having to shave the recording site, from sensors placed on the neck above the oesophagus, above the reticulum, above the dorsal sac and above the ventral sac, respectively. The recording illustrates the sequence of events starting with an old bolus descending down the oesophagus to the rumen, a contraction of the reticulum as a new bolus is trafficked to the mouth, followed thereafter by an A-sequence wave (mixing) that spreads across the dorsal sac and then later into the ventral sac and ends with the release of gas bubbles from the ventral blind sac up towards the sensor placed above the dorsal sac. Note the timing of events.

A close up of the rumen gas bubble sound sequences can be seen (see Figure 6). These sound sequences were of variable duration and frequency depending on the animals measured and their individual production level. However, they were easily detected with the aid of a stethescope used in combination with the AMG recordings. Sounds heard using a stethescope could be noted by an individual positioned alongside the animal being measured, whilst the user with the AMG real-time smart device took a screenshot of the sequence and noted the precise time of their occurrence. Thereafter it was relatively easy to identify such sequences based on their appearance and the timing of previous and subsequent events in the rumen.

Figure 6: A couple of typical AMG signals recorded through the skin without having to shave the recording site, from a sensor placed above the dorsal sac. The rumen sounds recorded originate from gas bubbles ascending from the ventral blind sac at the end of an A-sequence or as the result of a B-sequence forward moving contraction. White brackets indicate the sequence duration.

Discussion

This study, which has focused on a detailed analysis of the borborygmi from the left lateral abdominal cavity of cattle, is to the authors best knowledge the first of its kind. It lends support to an earlier study in which it was demonstrated that such transdermal recordings were feasible in large ruminants [1]. The findings of this study reveal that not only can specific sounds be recorded, they can be identified as having a specific origin, and that a combination of sensors applied to an animal can provide information about the sequence of events between the rumen chambers.

Chewing activity has been recorded in ruminants for some time, and even sound recordings with microphones have been used effectively to differentiate between feeding and rumination behaviours [7, 8]. Indeed, sound recordings of jaw movements in dairy cattle have been classified as one of four distinct categories: animals taking a bite of a foodstuff, exclusive chews (rumination), chew-bite combinations, and exclusive sorting of food material in the mouth. Recently Abdanan Mehdizadeh and colleagues used sound recordings of jaw movements to better understanding how cows consume different types of feed [9]. Their recordings were able to reveal potential health issues or deficiencies in the diets fed to production animals and they concluded that sound recordings could be used to improve feeding practices, reduce waste, and ensure the well-being and productivity of cattle [9]. In many ways the recordings made in the present study from a sensor placed on the neck above the oesophagus of cattle are complimentary to such published studies. They are also supplementary though, in that they provide details about the periods of rumination, the time taken ruminating each bolus and the connection between the mouth and the rumen chambers (see Figures 3 & 4).

The present study used piezo-ceramic sensors rather than microphones to detect and record rumen sounds. The use of these flat sensors has been shown to be vastly improved compared with standard microphones, as they become directional and do not record extraneous sounds such as environmental noises, speech patterns etc [10]. However, that is not to say that the present technique is without extraneous signal issues, as can be seen in Figure 2, since in order to record borborygmi they have first to traverse the rumen wall, subcutaneous tissues as well as the skin and hair of the subject of interest. It is important that sensor skin contact be optimized and that requires the application of an acoustic gel into the hair and through to the skin at the site of interest. Poor skin/sensor contact will greatly affect the detected and recorded signal. Indeed, insufficient acoustic gel, or a loose bandage around the sensor will result in weak signals as well as extraneous noise as the sensor intermittently makes contact with the hair and skin. Other factors can also affect the recorded borborygmi, such as subcutaneous muscles (e.g. m.Cutaneous trunci), which can be activated to contract when flies or other insects land on the subject during a recording. Such subcutaneous muscle contraction signals are presented in Figure 2 and they have a very characteristic profile, making them readily identifiable from other sounds. Finally, one should consider the anatomical location of the sensors when performing an acoustic recording from a cow. Particular attention should be taken when placing a sensor above the reticulum and guidance as to correct placement has been given in the Materials and Methods section (see Figure 1).

With the correct placement of the sensors, and a period of fly free recording, it is possible to detect rumen sounds and oesophagus sounds, which in combination can reveal the sequence of events that occur in the rumen: A- and B-wave sequences for mixing and eructation, respectively (see Figure 5). Indeed, it is also possible to detect and record the rumen sounds associated with microbial fermentation in the ventral sac and ventral blind sac (see Figure 6). At the end of an A-wave sequence the ventral blind sac contracts and any gas bubbles trapped therein float up into the dorsal sac and can be heard with the aid of a stethescope placed at the paralumbar fossa as distant thunder rumbles. With the aid of the present SOFi M2 units and sensors, it was not only possible to detect such gas bubble sounds, their intensity and duration could also be measured. This may prove invaluable in terms of assessing individual animals response to feeds with regard to optimizing feeding strategies and herd management at a time when CH4 emissions and global warming are so topical.

Conclusion

The present findings are of great interest for students of veterinary medicine, and fully qualified veterinarians alike. They are not only an educational tool, but such recordings as these also provide the basis for diagnosis in connection with rumen related issues [2, 3] and serve as a platform for those interested in the effects of nutritional changes in production cattle as well as assisting in the study of rumination and gas production (i.e. CO2 and CH4).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff at Taastrup and Assendrup for their kind help and assistance.

Conflict Of Interest

The authors know of no conflict concerning this study and this project was not funded by any source.

Data Availability

The source data to these analyses are available upon request.

References

- Vargas-Bello-Pérez E, Neves ALA, Harrison A. A non-invasive sound technology to monitor rumen contractions. Animals 12 (2022): 2164.

- Schwarzkopf S, Kinoshita A, Hüther L, et al. Weaning age influences indicators of rumen function and development in female Holstein calves. BMC Vet Res 18 (2022): 102.

- Abutarbush SM, Naylor JM. Obstruction of the small intestine by a trichobezoar in cattle: 15 cases (1992–2002). J Am Vet Med Assoc 229 (2006): 1627–1630.

- Caja G, Castro-Costa A, Salama A, et al. Sensing solutions for improving the performance, health, and wellbeing of small ruminants. J Dairy Res 87 (2020): 34–46.

- Russell JB, Rychlik J. Factors that alter rumen microbial ecology. Science 292 (2001): 1119–1122.

- Welch JG. Rumination time in four breeds of dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci 53 (1970): 89–91.

- Martínez Rau L, Chelotti JO, Vanrell SR, et al. Developments on real-time monitoring of grazing cattle feeding behavior using sound. Proc IEEE Int Conf Ind Technol (2020): 771–776.

- Mansbridge N, Mitsch J, Bollard N, et al. Feature selection and comparison of machine learning algorithms in classification of grazing and rumination behaviour in sheep. Sensors 18 (2018): 3532.

- Abdanan Mehdizadeh S, Sari M, Orak H, et al. Classifying chewing and rumination in dairy cows using sound signals and machine learning. Animals 13 (2023): 2874.

- Harrison AP. A more precise, repeatable and diagnostic alternative to surface electromyography—an appraisal of the clinical utility of acoustic myography. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging (2017).