Lower Mortality in Very Elderly Patients and Heart Failure Patients Admitted to the Hospital Having High Blood Pressure

Article Information

Isak Lindstedt1,2*, Lars Edvinsson2, Marie-Louise Edvinsson2

1Achima Care Ekeby vårdcentral, Storgatan 46, 26776, Ekeby, Sweden

2Department of Medicine, Institute of Clinical Sciences Lund, Lund University, Sweden

*Corresponding author: Isak Lindstedt, Achima Care Ekeby vårdcentral, Storgatan 46, 26776, Ekeby, Sweden

Received: 20 July 2019; Accepted: 29 July 2019; Published: 02 August 2019

Citation: Isak Lindstedt, Lars Edvinsson, Marie-Louise Edvinsson. Lower Mortality in Very Elderly Patients and Heart Failure Patients Admitted to the Hospital Having High Blood Pressure. Cardiology and Cardiovascular Medicine 3 (2019): 204-220.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Introduction: How to handle blood pressure in very elderly patients (> 80 years) is still debatable. Many are frail, dependent, and susceptible to drug interactions, and have not been included in blood pressure trials. Thus, how blood pressure levels in these patients predict future events remains unclear.

Methods: We studied a cohort of 339 elderly patients with a mean age of 83 years that visited the emergency department and were subsequently admitted into the hospital. We divided the cohort into two groups: 144 patients with blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mm Hg (HBP-group) and 195 patients with blood pressure < 140/90 mm Hg (NBP-group). Mean blood pressure in the HBP-group was 158/83 mm Hg and 122/70 mm Hg in the NBP-group. Furthermore, we also did a subgroup analysis on a total of 178 patients with heart failure, totaling 69 with high blood pressure with a mean of 155/85 mm Hg (HBPHF-group) and 109 without high blood pressure with a mean of 119/71 mm Hg (NBPHFgroup).

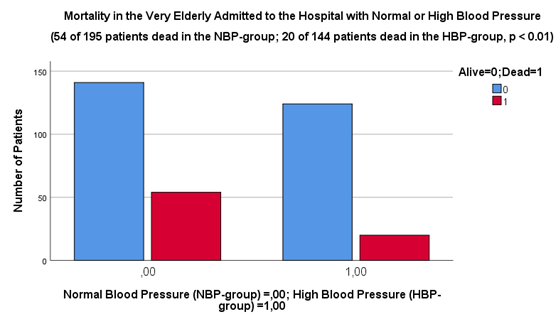

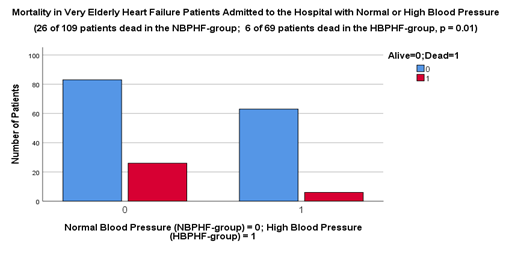

Results: After 6 months 20 patients were dead in the HBP-group compared to 54 patients in the NBP-group (p < 0.01). In the subgroup analysis, 6 patients were dead in the HBPHF-group and 26 patients were dead in the NBPHF-group after 6 months (p = 0.01).

Conclusions: We found that very elderly patients in general but also patients with heart failure in particular that presented with high blood pressure when enrolling into the hospital had significantly lower 6-month mortality than very elderly with normal blood pressure.

Keywords

Elderly; Blood Pressure; Heart Failure; Mortality; Hospital Admission

Article Details

Introduction

Hypertension has a very high prevalence in the world and its prevalence increases with age and many people are undiagnosed and undertreated, particularly in the elderly. The prevalence of hypertension is >60% in people aged >60 years with an overall prevalence in adults of between 30-45% [1]. Hypertension is also a well-known risk factor for cardiovascular disease in its own right and often coinciding with other risk factors like diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, smoking and obesity, leads to higher risk of ischemic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular insults such as heart attack and stroke [2]. As a result of vascular damage [3] and insults, hypertension ultimately leads to end-organ failure like heart failure, kidney failure and cognitive dysfunction and finally to higher mortality [4]. It is beyond a doubt that preventing hypertension or treating established hypertension decreases cardiovascular disease and mortality. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials including a large number of patients have revealed that a 10 mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure or a 5 mmHg reduction in diastolic blood pressure is associated with significant reductions in cardiovascular events [5]. Lifestyle interventions and antihypertensive drugs work together to improve the prognosis in these patients [6].

However, even though it is well established that hypertension increases risk and that treatment of hypertension is beneficial in young, middle-aged and elderly patients, it is still debatable how to handle the very elderly (> 80 years) with hypertension. Firstly, there is a worry that blood pressure lowering interventions may impair mechanisms in the very elderly that preserves blood pressure homeostasis and vital organ perfusion. Secondly, on the other hand large trials in the elderly and very elderly, The Sprint [7] and The Hyvet trials [8], have shown that antihypertensive treatment markedly reduces cardiovascular morbidity and mortality even in these age groups and a recent meta-analysis and systematic review have suggested that “treating to systolic blood pressure of 120 – 140 mm Hg versus higher targets benefited older patients more than younger patients without an age-related increase in relative risk for adverse effects [9]”. Thirdly, the fact is that most randomized controlled trials in general have not included very frail or dependent patients, or patients with orthostatic hypotension. It is therefore unclear whether such patients would profit from blood pressure lowering treatment having comorbidities of their own and having a life expectancy that could be different from less frail patients. Fourthly, the elderly also commonly take other drugs, which may interact with antihypertensive medication. Adverse effects can possibly be more numerous outside the context of randomized controlled trials since the fervent supervision in these trials may reduce adverse effects and motivate compliance [10].

Several observational studies have shown that higher blood pressure values in the very elderly can be protective and that too low blood pressure values may be hazardous [11-15]. Therefore, there is an inconsistency between the results of observational studies and randomized clinical trials which needs to be clarified further. In short, randomized clinical trials have the greater scientific evidence, but of necessity there is a reservation in that they have not been representative of a population of the very old. On the other hand, observational studies have a lower grade of evidence and cannot stand alone to prove cause and effect, but could possibly have included a more representative population.

One group of very elderly patients is the one that visits the emergency department for various symptoms. These patients are frail in the sense that they have several comorbidities, many medications, high prevalence of postural hypotension and they most likely have aggravating symptoms from their underlying conditions and conceivably new cardiovascular insults. There is ample evidence from cohort studies that low systolic blood pressure on admission to the hospital predicts in-hospital mortality and future mortality [16]. This is particularly true for certain selected patient populations like middle-aged to elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome and heart failure [17-23]. Although there is data that associate low systolic blood pressure on admission to future events in the middle-aged to elderly, there is still limited data in the very elderly (> 80 years) in this regard [24-25]. Also, heart failure is prevalent in the very elderly and deterioration in signs and symptoms of heart failure is a common cause of admission to the hospital. Increasing age in heart failure patients is associated with increased mortality in these patients [26]. We set out to determine if there would be a difference in mortality between those very elderly patients that presented at the emergency department and admitted to the hospital with high blood pressure compared to those whom presented with normal blood pressure. In other words, is the level of blood pressure in these frail patients a predictor of future mortality? Moreover, notably we wanted to explore possible mechanistic explanations for such an association.

Methods

Very elderly patients presenting at the emergency department of Lund University Hospital for various symptoms and subsequently admitted into the hospital for care were included in the study. There were no inclusion or exclusion criteria so the mix of patients in our study represented the general elderly population in the very southern part of Sweden that needed acute medical attention at the time of admission to the hospital. With the intent of studying orthostatic hypotension in the very elderly, a cohort of 339 patients with complete results of orthostatic blood pressure tests were gathered from 2014 to 2018. Two hundred and ten of these patients obtained from 2014 until May 2017 have been evaluated in this regard and the results have been published elsewhere [27]. For the purposes of our present study we used the whole cohort of 339 patients. The main reason for this was the very high mean age in this cohort which consequently made it possible for us to evaluate our thesis.

We divided the cohort into two groups: 144 patients that had a blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mm Hg (HBP-group) and 195 patients that had a blood pressure < 140/90 mm Hg (NBP-group). Furthermore, we also did a subgroup analysis on a total of 178 patients. The rationale for doing this was to be able to evaluate the association of heart failure with blood pressure in the very elderly. The number of heart failure patients in the original cohort of 339 patients was a little low in absolute numbers (n = 80) and an additional number of patients seemed logical in order to increase the power to make a meaningful evaluation. Accordingly, in the subgroup analysis we excluded those 259 of the 339 patients from the original cohort that did not have heart failure and merge the remaining 80 heart failure patients from this original cohort with an additional 98 patients from another cohort (described below) representing only patients with heart failure. This gave two subgroups with only heart failure patients totaling 69 with high blood pressure (HBPHF-group) and 109 without high blood pressure (NBPHF-group). The 98 additional patients with heart failure represented a cohort of patients gathered during the period 2013 – 2015. They had been admitted to the internal medicine ward at Lund University Hospital. The criteria for inclusion was: 1) They had been given the primary diagnosis of heart failure; 2) The NT-proBNP tests had been taken at least twice during the hospital stay and that at least one of these tests recorded a value of above 4000 ng/L; 3) Creatinine had to be taken at least once during the hospital stay.

Previous smaller studies on the subject that were able to detect a difference in outcome included 581 patients [20], 368 patients [21], and 71 patients [28]. The first two of these categorized blood pressures levels into several parts, 4 quartiles [20] and 5 quintiles [21] respectively, thus needing a larger number of patients. The last of these studies categorized blood pressure into only two categories needing fewer patients to detect a difference [28]. We decided to examine only two blood pressure categories.

For the patients in this study, there were a variety of presenting symptoms and diagnoses at both hospital admittance and discharge. Thus, we decided to only report data for those symptoms and diagnoses where the number of cases was suf?cient to make meaningful comparisons. The main complaints at admission, i.e. the patients’ most frequently recurring symptoms were noted. We did not attempt to describe the included patients’ previous diseases since the study was open to any elderly patient, making it rational to decide that the included study population would be a reasonable representation of the general Swedish population in their eighties coming to the hospital for medical attention. We attained relevant information about the patients from their medical records. We obtained basic demographic information about age, gender, pulse, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, symptoms and laboratory data at admission. We recorded types of drugs and diagnoses at discharge, number of drugs at admission and discharge, and number of deaths within 6 months. Six month all-cause mortality was confirmed by reviewing the patients’ medical records and confirming which patients were alive and which were not 6 month after discharge from the hospital, also checking with the Swedish National Death Registry when needed.

Total cardiovascular disease was de?ned as a combined endpoint of the following diagnoses at discharge: heart failure, heart attack, arrhythmias, cerebral ischemia or bleeds, lung embolus, hypertension, hypotension, diabetes, and renal failure. Total lung disease was a combined endpoint of the following diagnoses: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, pneumonia, lung cancer, and pneumothorax. Total infectious disease was a combined endpoint of the following diagnoses: sepsis, urinary tract infection, in?uenza, erysipelas, or infection unspeci?ed. The ?nal diagnosis was made based on good clinical practice and according to the ICD-10, International Statistical Classi?cation of Diseases and Related Health Problems.

This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund, Sweden, D.no 2016/819. The study conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistics

Calculations for comparison between the two groups were done using the Student’s T-test for continuous variables and the Pearson’s Chi-square test for dichotomous variables. Statistical signi?cance was set at p < 0.05. Correlations were calculated with the Pearson’s Coefficient and results were only reported from the subgroup and results that correlated with resting pulse or blood pressure or NT-proBNP and eGFR and reached a statistical signi?cance of p<0.01. Statistics were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 22 program.

Results

Overall demographics, laboratory data, medications used, inter alia, are given in Table 1. There was no difference in basic parameters such as age, gender, BMI, pulse, and saturation levels between the HBP- and the NBP-groups. The difference in blood pressure between the two groups was marked (in SBP 36 mmHg and in DBP 13 mmHg; p<0.01). There was somewhat more use of diuretics in the NBP-group and somewhat more use of anti-hypertensives in the HBP-group. After 6 months 20 patients were dead in the HBP-group compared to 54 patients in the NBP-group (p < 0.01) (Figure 1).The HBP-group had significantly less heart failure patients (p < 0.01), less patients with cancer (p < 0.05), fewer medications (p < 0.01), lower NT-proBNP- (p < 0.05) and CRP-values (p < 0.05) and higher Hb (p < 0.05) and Na+ values (p < 0.01) than the NBP-group at baseline.

|

Demographics |

|||||||

|

High Blood Pressure (HBP-group) |

Normal Blood Pressure (NBP-group) |

||||||

|

N |

SEM/% |

N |

SEM/% |

P-value |

|||

|

Age |

83.8 |

144 |

± 0.68 |

82.0 |

195 |

± 0.62 |

0.07 |

|

Gender, Males |

57 |

144 |

40 % |

79 |

195 |

41 % |

0.86 |

|

BMI |

24.1 |

92 |

± 0.57 |

23.5 |

121 |

± 0.41 |

0.41 |

|

Pulse |

80.7 |

144 |

± 1.35 |

81.5 |

193 |

± 1.05 |

0.62 |

|

SBP |

158 |

144 |

± 1.35 |

122 |

195 |

± 0.91 |

< 0.01 |

|

DBP |

83.0 |

144 |

± 1.01 |

70.3 |

195 |

± 0.70 |

< 0.01 |

|

Sa02 |

95.8 |

137 |

± 0.22 |

95.5 |

190 |

± 0.21 |

0.40 |

|

Orthostatic |

70 |

144 |

49 % |

80 |

195 |

41 % |

0.17 |

|

Medicines Admission |

10.8 |

121 |

± 0.56 |

12.6 |

166 |

± 0.40 |

0.01 |

|

Medicines Discharge |

10.0 |

144 |

± 0.45 |

11.1 |

195 |

± 0.37 |

0.07 |

|

Diuretics |

68 |

144 |

47 % |

114 |

195 |

58 % |

0.04 |

|

Beta-blockers |

67 |

144 |

46 % |

107 |

195 |

55 % |

0.13 |

|

Anti-hypertensives |

45 |

144 |

31 % |

37 |

195 |

19 % |

0.01 |

|

Diabetes Medicine |

18 |

144 |

13 % |

17 |

195 |

8.7 % |

0.26 |

|

ARB |

13 |

144 |

9.0 % |

26 |

195 |

13 % |

0.22 |

|

Spironolactone |

14 |

144 |

10 % |

42 |

195 |

22 % |

< 0.01 |

|

Digoxin |

13 |

144 |

9.0 % |

21 |

195 |

11 % |

0.60 |

|

Insulin |

11 |

144 |

7.6 % |

12 |

195 |

6.0 % |

0.59 |

|

Imdur |

16 |

144 |

11 % |

19 |

195 |

10 % |

0.68 |

|

ACE-inhibitors |

35 |

144 |

24 % |

60 |

195 |

31 % |

0.19 |

|

Dyspnea |

45 |

144 |

31 % |

61 |

195 |

31 % |

0.96 |

|

Chest Pain |

6 |

144 |

4.1 % |

20 |

195 |

10 % |

0.04 |

|

Syncope/Falls/Dizziness |

43 |

144 |

30 % |

49 |

195 |

25 % |

0.33 |

|

Total Cardiovascular |

88 |

144 |

61 % |

120 |

195 |

62 % |

0.94 |

|

Total Lung |

25 |

144 |

17 % |

38 |

195 |

19 % |

0.62 |

|

Total Infectious |

29 |

144 |

20 % |

44 |

195 |

23 % |

0.59 |

|

Diabetes |

8 |

144 |

5.5 % |

9 |

195 |

4.6 % |

0.70 |

|

Hypertension |

15 |

144 |

10 % |

17 |

195 |

8.7 % |

0.60 |

|

Cognitive Decline/Dementia |

4 |

144 |

2.7 % |

5 |

195 |

2.5 % |

0.90 |

|

Congestive Heart Failure |

28 |

144 |

19 % |

63 |

195 |

32 % |

< 0.01 |

|

Cancer |

12 |

144 |

8.3 % |

31 |

195 |

16 % |

0.04 |

|

Atrial Fibrillations |

26 |

144 |

18 % |

31 |

195 |

16 % |

0.60 |

|

COPD |

20 |

144 |

14 % |

25 |

195 |

13 % |

0.77 |

|

Renal Failure |

11 |

144 |

7.6 % |

7 |

195 |

3.5 % |

0.10 |

|

Mortality |

20 |

144 |

14 % |

54 |

195 |

28 % |

< 0.01 |

|

CRP |

35.2 |

94 |

± 5.06 |

54.4 |

135 |

± 6.64 |

0.03 |

|

Glucose |

7.09 |

95 |

± 0.28 |

6.94 |

131 |

± 0.28 |

0.70 |

|

NT-proBNP |

2733 |

40 |

± 754 |

5449 |

60 |

± 924 |

0.04 |

|

TnT |

33.1 |

59 |

± 4.03 |

51.6 |

76 |

± 12.5 |

0.21 |

|

Creatinine |

101 |

95 |

± 5.74 |

99.0 |

136 |

± 4.12 |

0.78 |

|

Sodium |

140 |

95 |

± 0.36 |

138 |

136 |

± 0.34 |

< 0.01 |

|

Potassium |

3.96 |

95 |

± 0.05 |

4.06 |

136 |

± 0.04 |

0.12 |

|

Hb |

128 |

95 |

± 1.76 |

122 |

136 |

± 1.47 |

0.02 |

|

eGFR |

51.4 |

75 |

± 2.85 |

50.1 |

112 |

± 2.31 |

0.71 |

|

CRP (C-reactive protein (mg/L)); Glucose (mmol/L); NT-proBNP (ng/L); TNT (Troponin T (ng/L)); Creatinine (µmol/L); Sodium (mmol/L); Potassium (mmol/L); Hemoglobin (g/L); e-GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2); SEM (Standard Error of the Mean); Antihypertensives – mainly Ca2+ channel blockers; Total cardiovascular, lung, infecious – see Methods section. |

|||||||

Table 1: Overall demographics, laboratory data, medications used for the High Blood Pressure (HBP-group) and Normal Blood Pressure (NBP-group) groups are given in Table 1.

|

Demographics |

|||||||

|

High Blood Pressure (HBPHF-group) |

Normal Blood Pressure (NBPHF-group) |

||||||

|

N |

SEM/% |

N |

SEM/% |

P-value |

|||

|

Age |

83.1 |

69 |

± 1.19 |

82.9 |

109 |

± 0.73 |

0.92 |

|

Gender, Males |

38 |

69 |

55 % |

58 |

109 |

53 % |

0.81 |

|

BMI |

25.6 |

63 |

± 0.63 |

24.7 |

88 |

± 0.50 |

0.24 |

|

Pulse rest |

83 |

54 |

± 2.51 |

83 |

99 |

± 1.52 |

0.96 |

|

SBP |

155 |

69 |

± 2.24 |

119 |

109 |

± 1.23 |

< 0.01 |

|

DBP |

84.6 |

69 |

± 1.73 |

70.9 |

109 |

± 1.01 |

< 0.01 |

|

Number of Medicines |

12.6 |

63 |

± 0.60 |

13.6 |

97 |

± 0.51 |

0.22 |

|

Diuretics |

61 |

69 |

88 % |

93 |

109 |

85 % |

0.56 |

|

Beta-blockers |

55 |

69 |

80 % |

94 |

109 |

86 % |

0.25 |

|

Anti-hypertensives |

5 |

69 |

7.2 % |

4 |

109 |

3.6 % |

0.03 |

|

ARB |

11 |

69 |

16 % |

22 |

109 |

20 % |

0.48 |

|

Spironolactone |

26 |

69 |

38 % |

41 |

109 |

38 % |

0.99 |

|

Digoxin |

4 |

69 |

5.8 % |

13 |

109 |

12 % |

0.18 |

|

Imdur |

4 |

69 |

5.8 % |

11 |

109 |

10 % |

0.97 |

|

ACE-inhibitors |

47 |

69 |

68 % |

64 |

109 |

59 % |

0.21 |

|

Dyspnea |

59 |

69 |

86 % |

73 |

109 |

67 % |

< 0.01 |

|

Chest Pain |

3 |

69 |

4.3 % |

10 |

109 |

9.1 % |

0.23 |

|

Syncope/Falls/Dizziness |

2 |

69 |

2.9 % |

11 |

109 |

10 % |

0.07 |

|

Diabetes |

23 |

69 |

33 % |

26 |

109 |

24 % |

0.17 |

|

Congestive Heart Failure |

69 |

69 |

100 % |

109 |

109 |

100 % |

N/A |

|

Cancer |

2 |

69 |

2.9 % |

7 |

109 |

6.4 % |

0.30 |

|

Atrial Fibrillations |

28 |

69 |

41 % |

35 |

109 |

32 % |

0.25 |

|

COPD |

7 |

69 |

10 % |

13 |

109 |

12 % |

0.71 |

|

Mortality |

6 |

69 |

8.7 % |

26 |

109 |

24 % |

0.01 |

|

CRP |

26.1 |

57 |

± 5.77 |

32.1 |

89 |

± 5.67 |

0.48 |

|

Glucose |

8.21 |

58 |

± 0.35 |

7.22 |

87 |

± 0.35 |

0.06 |

|

NT-proBNP |

9453 |

57 |

± 1243 |

7470 |

79 |

± 690 |

0.14 |

|

TnT |

58.7 |

52 |

± 7.95 |

94.1 |

76 |

± 24.5 |

0.25 |

|

Creatinine |

107 |

58 |

± 6.10 |

115 |

89 |

± 4.82 |

0.33 |

|

Sodium |

139 |

58 |

± 0.53 |

139 |

89 |

± 0.39 |

0.42 |

|

Potassium |

4.01 |

58 |

± 0.06 |

4.14 |

89 |

± 0.05 |

0.10 |

|

Hb |

128 |

58 |

± 2.30 |

129 |

89 |

± 1.91 |

0.75 |

|

eGFR |

45.1 |

57 |

± 2.98 |

45.2 |

83 |

± 2.10 |

0.98 |

|

CRP (C-reactive protein (mg/L)); Glucose (mmol/L); NT-proBNP (ng/L); TNT (Troponin T (ng/L)); Creatinine (µmol/L); Sodium (mmol/L); Potassium (mmol/L); Hemoglobin (g/L); e-GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2); SEM (Standard Error of the Mean); Antihypertensives – mainly Ca2+ channel blockers. |

|||||||

Table 2: Overall demographics, laboratory data, medications used for the High Blood Pressure (HBPHF-group) and Normal Blood Pressure (NBPHF-group) groups are given in Table 2.

We made a subgroup analysis in heart failure patients and observed that in this, 6 patients were dead in the HBPHF-group and 26 patients were dead in the NBPHF-group after 6 months (p = 0.01) (Figure 2). As noted in Table 2 there were only minor differences in demographics, laboratory data and drug use. There were more hypertensive drugs (although the absolute number of drugs were few) and more heart failure patients with dyspnea in the HBPHF-group compared with the NBPHF-group in the subgroup analysis.

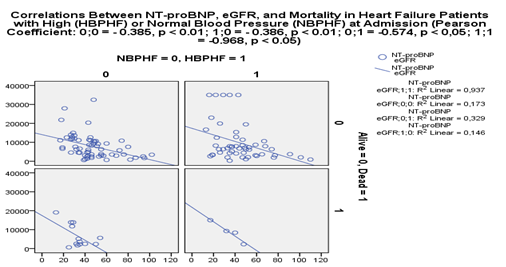

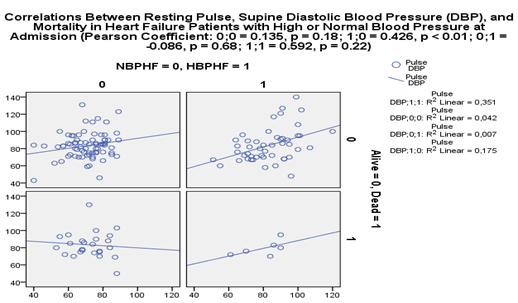

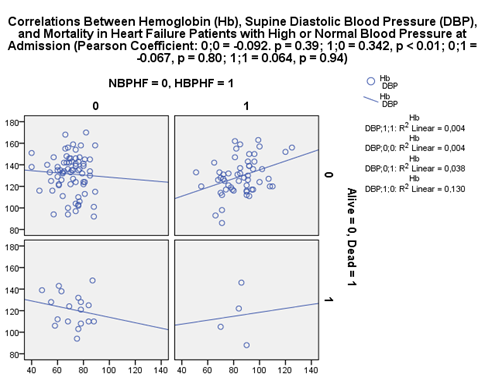

We also performed correlative analysis of the data and this gave the following results: 1) NT-proBNP and eGFR correlated negatively in both the NBPHF-group and the HBPHF-group, Figure 3 (Pearson Coefficient: 0;0 = - 0.385, p < 0.01; 1;0 = - 0.386, p < 0.01; 0;1 = -0.574, p < 0.05; 1;1 = -0.968, p < 0.05). 2) Pulse correlated positively with diastolic blood pressure in the HBPHF-group but not in the NBPHF-group, Figure 4 (Pearson Coefficient: 0;0 = 0.135, p = 0.18; 1;0 = 0.426, p < 0.01; 0;1 = -0.086, p = 0.68; 1;1 = 0.592, p = 0.22). 3) Hemoglobin correlated positively with diastolic blood pressure in the HBPHF-group but not in the NBPHF-group, Figure 5 (Pearson Coefficient: 0;0 = -0.092. p = 0.39; 1;0 = 0.342, p < 0.01; 0;1 = -0.067, p = 0.80; 1;1 = 0.064, p = 0.94).

Discussion

The main findings in this real-life study of elderly frail patients revealed that very elderly patients that presented with high blood pressure when enrolling into the hospital had a significantly lower 6-month mortality than very elderly with normal blood pressure. This result may appear contradictory to trials in healthy elderly. However, our study clearly shows that the very elderly with high blood pressure were less sick at baseline than their counterpart with normal blood pressure and thus had better chances of survival. After 6 months 20 patients were dead in the HBP-group compared to 54 patients in the NBP-group (p < 0.01). The HBP-group had significantly less heart failure patients (p < 0.01), less patients with cancer (p = 0.04), fewer medications (p < 0.01), lower NT-proBNP- (p = 0.04) and CRP-values (p = 0.03), and higher Hemoglobin (p = 0.02) and Na+ values (p < 0.01) than the NBP-group at baseline. The result suggested that there were an overrepresentation of patients with heart failure in the NBP-group and it is well known that heart failure patients have a poor prognosis with high mortality [29]. When studying the same blood pressure categories in a cohort of very elderly patients that had heart failure as a common diagnosis, there were no major differences at baseline between the groups. Also, correlative studies revealed similar correlations between NT-proBNP and eGFR in both the NBPHF-group and the HBPHF-group, suggesting that the findings in the subgroup analysis was not caused by renal failure. Yet, even though the difference in sickness at baseline between the groups essentially disappeared in the subgroup analysis, the HBPHF-group still had lower mortality. Six patients were dead in the HBPHF-group and 26 patients were dead in the NBPHF-group after 6 months (p = 0.01). Lastly, and most importantly, this is to the best of our knowledge the first study to investigate possible mechanisms explaining why heart failure patients with high admission blood pressure had lower mortality. Previous studies have discussed hypothetical reasons for the association rather than investigating the matter further [17-25, 28]. Since our study, in opposition to previous studies, included diastolic as well as systolic blood pressure, correlative analyses of the data showed that the diastolic blood pressure, rather than the systolic blood pressure, could give valuable pathophysiological insight. The reason given for only studying the systolic blood pressure was that systolic blood pressure increases with age while diastolic blood pressure does not and thus the prognostic significance of systolic blood pressure would differ with increasing age [24].

The primary question we asked was whether high blood pressure (at reasonable levels) in this context could be seen as a protective factor and, at the same time, normal or low blood pressure could be seen as a risk factor in the very elderly? A commonly accepted mechanism is that too low blood pressure levels in the very elderly may alter blood pressure homeostasis and vital organ perfusion. This may lead to acute or chronic ischemic damage that ultimately result in an insult like a heart attack or stroke that in turn ensuing to immediate death or organ failure like heart failure, renal failure or cerebral dysfunction resulting ultimately in greater mortality. But at what level is blood pressure too low in the very elderly? Obviously the blood pressure is too low if at a certain level it is the cause of ischemia or symptoms like dizziness, fainting, tiredness, heart palpitations etc. Kajimoto et al [24] proposed that “the ability of elderly patients to maintain systolic blood pressure in the acute phase of AHFS (acute heart failure syndrome) may reflect a cardiovascular reserve that is mediated by a stronger vasoconstrictor response rather than a larger contractile reserve.” They also suggested that based on “previous reports and their own findings, it seems possible that an elevated baseline systolic blood pressure may have a protective effect in elderly patients rather than younger patients, since it reflects an adequate response to acute stress and prevents the development of non-cardiac comorbidities.”

A classic example of too low blood pressure is in orthostatic hypotension where the patient upon standing from the supine position becomes symptomatic because of a sudden lowering of blood pressure. The prevalence of orthostatic hypotension is very high in the very elderly. For example, Weiss et al found that in patients with a mean age of 81.6 years admitted to an acute geriatric ward 34.8% had persistent orthostatic hypotension [30]. Persistent orthostatic hypotension was defined as having an orthostatic reaction to two orthostatic tests in one day. Szyndler et al invited 209 patients with the mean age of 84 years from one primary care clinic. In their study the prevalence of orthostatic hypotension was 38.3% [31]. We had a prevalence of orthostatic hypotension of 44.2% in our study population. Importantly, in our population there was no significant difference between the number of orthostatic patients in the very elderly with high blood pressure and the group with normal blood pressure (70/144 vs. 80/195, p = 0.17). Orthostatic hypotension has been associated with increased mortality, whereas in the elderly the results are not consistent [32].

The two study populations differed quite a bit in blood pressure at baseline. In the high blood pressure group, HBPHF-group, the resting blood pressure was 155/85 mm Hg and 119/71 mm Hg in the normal blood pressure group, NBPHF-group. Since the absolute medium values in the two groups respectively were quite far from the standard cut-off definition of hypertension of < 140/90 mm Hg, we might speculate that in the HBPHF-group and the NBPHF-group there would be a few patients with extreme high blood pressure values or extreme low blood pressure values that possibly were sicker than the rest. Were there possibly more or less of these outliers in the NBPHF-group or in the HBPHF-group contributing to the mortality? This was unlikely since when comparing the group of outliers (patients with Grade III systolic blood pressure, ≥ 180 mm Hg, plus patients with low blood pressure defined as systolic blood pressure < 110 mm Hg) with the rest of the patients (a group with a systolic blood pressure of ≥ 110 mm Hg but < 180 mm Hg), there was no significant statistical difference in mortality (7 deaths/40 outliers; 25 deaths/138 non-outliers, p = 0.93).

Moreover, the medium resting pulse was quite the same in the two groups, 81 beats/minute in the HBP-group (83 HBPHF-group) and 82 beats/minute in the NBP-group (83, NBPHF-group), p = 0.62 (p = 0.96). We might speculate that the values of the resting pulse in the NBP-group would have been significantly higher than in the HBP-group since a low blood pressure state would increase heart rate in a compensatory manner in order to increase cardiac output. Sympathetic outflow to the heart and blood vessels increase and cardiac vagal nerve activity decreases which in turn leads to increased vascular tone, heart rate and cardiac contractility which stabilizes the blood pressure. Moreno?González et al [33] recently showed that in an elderly population firstly hospitalized due to acute heart failure, the simple combined admission measurement of systolic blood pressure and heart rate predicted higher risk for 1-year all-cause mortality. One-year mortality ranged from 16.5% for patients in the low-risk group (heart rate < 70 bpm and systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, n=92) to 50% for those in the high-risk group (heart rate ≥ 70 bpm and systolic blood pressure < 120 mmHg, n=152). This study is especially relevant to our study since the mean age was 83 years, the same mean age as in our study, and the cohorts were of about the same size. One important difference was that in the Spanish study, the patients were included in the study based on their first acute heart failure admission, while in our study we did not exclude patients with previous known heart failure admissions. We might speculate that heart failure patients in our study had suffered from their disease for a longer period of time and that the compensatory mechanisms, like increased heart rate, were disabled. However, it is clear that the autonomic nervous system was at least partly functional in both groups in our study since they both displayed adequate increases in heart rate upon standing from a supine position (data not published). Also, there was no significant difference between the groups when it came to medication that can decrease heart rate like beta-blocker usage, 67/144 (HBP-group) vs. 107/195 (NBP-group), p = 0.13.

Moreover, pulse correlated positively with diastolic blood pressure in the HBPHF-group but not in the NBPHF-group that were alive after 6 months. On the other hand, rather pulse was negatively correlated with diastolic blood pressure among those in the NBPHF-group that died after 6 months, even though this correlation was not significant. One could propose that heart failure patients that came to the hospital having high blood pressure had the ability to preserve a higher pulse for every increase in blood pressure. This in turn could have been a possible mechanism that helped favor the HBPHF-group, an intact autonomic nervous system that assisted the propagation of blood flow to the organs of the body. Opposite, those patients that presented to the hospital with normal or low blood pressure had lost the ability to increase pulse and blood pressure in tandem. Especially for those in the NBPHF-group that died after 6 months there was seen an increase in pulse for every lowering of the blood pressure, a counter measure against a diminished cardiac output, but unfortunately too late.

Also, Hemoglobin count correlated positively with diastolic blood pressure in the HBPHF-group but not in the NBPHF-group. On the other hand, rather the Hemoglobin count was negatively correlated with diastolic blood pressure in the NBPHF-group, even though this correlation was not significant. One could propose that heart failure patients that came to the hospital having high blood pressure had the ability to retain a higher hemoglobin count for every increase in blood pressure. This, together with the higher pulse, could be a possible mechanism that helps favor the HBPHF-group, delivering more oxygen to vital organs. Opposite, those patients that presented to the hospital with normal or low blood pressure had lost the ability to retain hemoglobin and blood pressure in tandem. Instead in the NBPHF-group there was seen an increase in hemoglobin count for every lowering of blood pressure, a counter measure against a diminished cardiac output, but probably too late.

A very important distinction to be made in our study is whether the very elderly that came to the hospital had an acute increase in blood pressure because of an aggravating condition or they had a habitual high blood pressure, i.e. hypertension, very similar to the blood pressure they presented with? In the same manner, the same question could be asked the other way around concerning the very elderly with normal blood pressure. This question could partly be answered by checking if the patients in our study had known hypertension from before. Unfortunately, the anamnestic information from the medical records was not complete in this regard. What we do know is that there were more patients in the high blood pressure group that received antihypertensive medication, 45/144, than in the normal blood pressure group, 37/195 (p = 0.01). This was also true when examining the heart failure cohort (p = 0.03). There was no difference in the number of patients between the two groups with the diagnosis of hypertension at discharge (p = 0.60). The use of medication at admission can be linked to occurrence of sickness while the use of medication at discharge affects the prognosis during the follow-up time of the study [18]. Erne et al [34] tried to answer this question in patients admitted to the hospital with acute coronary syndrome. They found that patients with preexisting hypertension hade more favorable in-hospital mortality than patients without previously diagnosed hypertension. Independent predictors of better outcome was among others a lower admission systemic blood pressure. On the other hand, preexisting hypertension was not an independent predictor of 1-year mortality in these patients. Along the same lines, Lee et al [35] also found that low systolic blood pressure on presentation was independently associated with in-hospital mortality in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome, but on the contrary prior hypertension was not. They also found that patients with prior hypertension were more likely to be on antihypertensive medication before admission.

Strengths: Our study has several strengths. Firstly, we are to the best of our knowledge, the first to do additional investigations, correlations, into the mechanism explaining why heart failure patients with high admission blood pressure have lower mortality. Secondly, since our study included diastolic as well as systolic blood pressure, correlative analyses of the data showed that the diastolic blood pressure, rather than the systolic blood pressure would be worth looking into ahead when studying this association. Thirdly, we performed an open, retrospective study to convey real sickness and comorbidities in current time. Fourthly, there is still a need to study the very elderly, a growing group worldwide, because of the lack of number of studies in this age group relative to other age groups, and the uncertainty of how to treat their blood pressure. Fifthly, this study has shed further light onto the matter by showing that very elderly patients from the general population that presented with high blood pressure when enrolling into the hospital had a significantly lower mortality than very elderly with normal blood pressure. Furthermore, this study also reconfirmed the results of previous studies on the association between admission blood pressure and heart failure.

Weaknesses: Our study has several weaknesses. Firstly, the study cohort of 339 patients that we examined had been referred from the emergency room to the relevant ward for treatment. The cohort was representative of the very elderly that were admitted to the hospital but with one important selection bias. Only the very elderly that performed an orthostatic blood pressure test were part of this cohort. That means that patients that for any reason could not or would not be a part of this testing were excluded from our research. As a consequence, we might have lost data from the very sickest elderly patients, for example those that were too sick to stand up. Secondly, we did not attempt to adjust for any confounders, but did perform a relevant subgroup analysis. Thirdly, our results do not allow us to make the conclusion that high systolic admission blood pressure in the very elderly is a protective factor.

Summary

We found that very elderly patients that presented with high blood pressure when enrolling into the hospital had significantly lower 6-month mortality than very elderly with normal blood pressure. When studying a cohort of patients that had heart failure in common, very elderly heart failure patients admitted with high blood pressure still had lower mortality than their counterparts.

Acknowledgements

There are no acknowledgements, conflicts of interest or funding for this project.

References

- Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, Islam S, Gupta R, Avezum A, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA 310 (2013): 959–968.

- Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Ohman EM, Hirsch AT, Ikeda Y, Mas JL, et al. International prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 295 (2006): 180–189.

- Lindstedt I, Edvinsson ML, Edvinsson L. Reduced responsiveness of cutaneous microcirculation in essential hypertension--a pilot study. Blood Press 15 (2006): 275-280.

- Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 360 (2002): 1903–1913.

- Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, Anderson SG, Callender T, Emberson J, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 387 (2016): 957–967.

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 34 (2013): 2159–2219.

- Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, Berlowitz DR, Campbell RC, Chertow GM, et al. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 315 (2016): 2673–2682.

- Beckett N, Peters R, Leonetti G, Duggan J, Fagard R, Thijs L, et al. Subgroup and per-protocol analyses from the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial. J Hypertens 32 (2014): 1478–1487.

- Roush GC, Zubair A, Singh K, et al. Does the benefit from treating to lower blood pressure targets vary with age? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens 37 (2019): 1558-1566.

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens 36 (2018): 1953-2041.

- Mattila K, Haavisto M, Rajala S, Heikinheimo R. Blood pressure and five year survival in the very old. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 296 (1988): 887–889.

- Satish S, Freeman DH Jr, Ray L et al. The relationship between blood pressure and mortality in the oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc 49 (2001): 367–374.

- Oates DJ, Berlowitz DR, Glickman ME, Silliman RA, Borzecki AM. Blood pressure and survival in the oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc 55 (2007): 383–388.

- Benetos A, Labat C, Rossignol P, et al. Treatment with multiple blood pressure medications, achieved blood pressure, and mortality in older nursing home residents. The PARTAGE Study. JAMA Intern Med 175 (2015): 989-995.

- Streit S, Poortvliet RKE, Gussekloo J. Lower blood pressure during antihypertensive treatment is associated with higher all-cause mortality and accelerated cognitive decline in the oldest-old. Data from the Leiden 85-plus Study. Age and Ageing 47 (2018): 545–550.

- Segal O, Segal G, Leibowitz A, Goldenberg I, Grossman E, Klempfner R. Elevation in systolic blood pressure during heart failure hospitalization is associated with increased short and long-term mortality. Medicine (Baltimore) 96(5) (2017): e5890.

- Shlomai G, Kopel E, Goldenberg I, Grossman E. The association between elevated admission systolic blood pressure in patients with acute coronary syndrome and favorable early and late outcomes. J Am Soc Hypertens 9 (2015): 97-103.

- Stenestrand U, Wijkman M, Fredrikson M, Nyström FH. Association between admission supine systolic blood pressure and 1-year mortality in patients admitted to the intensive care unit for acute chest pain. JAMA 303 (2010): 1167-1172.

- Gheorghiade M, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Greenberg BH, O´Connor CM, She L, et al. Systolic blood pressure at admission, clinical characteristics, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. JAMA 296 (2006): 2217-2226.

- Pérez-Calvo JI, Montero-Pérez-Barquero M, Camafort-Babkowski M, Conthe-Gutiérrez P, Formiga F, Aramburu-Bodas O, et al. Influence of admission blood pressure on mortality in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. QJM 104 (2011): 325-33.

- Buiciuc O, Rusinaru D, Lévy F, Peltier M, Slama M, Leborgne L, et al. Low systolic blood pressure at admission predicts long-term mortality in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Cardiac Fail 17 (2011): 907-915.

- Rosman Y, Kopel E, Shlomai G, Goldenberg I, Grossman E. The association between admission systolic blood pressure of heart failure patients with preserved systolic function and mortality outcomes. Eur J Intern Med 26 (2015): 807-812.

- Al-Lawati JA, Sulaiman KJ, Al-Zakwani I, Alshejkh AA, Panduranga P, Al-Habib KF, et al. Systolic Blood Pressure on Admission and Mortality in Patients Hospitalized With Acute Heart Failure: Observations From the Gulf Acute Heart Failure Registry. Angiology 68 (2017): 584-591.

- Kajimoto K, Sato N, Takano T. Association of age and baseline systolic blood pressure with outcomes in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure syndromes. Int J Cardiol 191 (2015): 100-106.

- Vidán MT, Bueno H, Wang Y, Schreiner G, Ross JS, Chen J, et al. The relationship between systolic blood pressure on admission and mortality in older patients with heart failure.Eur J Heart Fail 12 (2010): 148–155.

- Gustafsson F, Torp-Pedersen C, Seibaek M, Burchardt H, Købner L. DIAMOND study group. Effect of age on short and long-term mortality in patients admitted to the hospital with congested heart failure. Eur Heart J 25 (2004): 1711-1717.

- Lindstedt I, Edvinsson L, Lindberg AL, Olsson M, Dahlgren C, Edvinsson ML. Increased all-cause mortality, total cardiovascular disease and morbidity in hospitalized elderly patients with orthostatic hypotension. Arch Gen Intern Med 2 (2018): 8-15.

- Kawase Y, Kadota K, Nakamura M, Tada T, Hata R, Miyawaki H, et al. Low systolic blood pressure on admission predicts mortality in patients with acute decompensated heart failure due to moderate to severe aortic stenosis. Circ J 78 (2014): 2455-2459.

- Gustafsson F, Torp-Pedersen C, Brendorp B, et al; DIAMOND Study Group. Long-term survival in patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure: relation to preserved and reduced left ventricular systolic function. Eur Heart J 24 (2003): 863-70.

- Weiss A, Grossman E, Beloosesky Y, Grinblat J. Orthostatic hypotension in acute geriatric ward: is it a consistent finding? Arch Intern Med 162 (2002): 2369-2374.

- Szyndler A, Derezinski T, Wolf J, Narkiewicz K. Impact of orthostatic hypotension and antihypertensive drug treatment on total and cardiovascular mortality in a very elderly community-dwelling population. J Hypertens 37 (2019): 331-338.

- Grossman E. Orthostatic hypotension: is it a predictor of total and cardiovascular mortality in the elderly? J Hypertens 37 (2019): 284-286.

- Moreno?González R, Formiga F, Mora Lujan JM, Chivite D, Ariza?Solé A, Corbella X. Usefulness of systolic blood pressure combined with heart rate measured on admission to identify 1-year all-cause mortality risk in elderly patients firstly hospitalized due to acute heart failure. Aging Clin Exp Res 21 (2019).

- Erne P, Radovanovic D, Schoenenberger AW, Bertel O, Kaeslin T, Essig M, et al. Impact of hypertension on the outcome of patients admitted with acute coronary syndrome. J Hypertens 33 (2015): 860-867.

- Lee D, Goodman SG, Fox KA, DeYoung JP, Lai CC, Bhatt DL, et al. Prognostic significance of presenting blood pressure in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome in relation to prior history of hypertension. Am Heart J 166 (2013): 716-722.