Long-Term Care for the Elderly is Determined by a Causal Link to Lifestyle, Three Health Factors Based on Socioeconomic Status

Article Information

Tanji Hoshi*

Department of Urban Science, Tokyo Metropolitan University, Japan

Corresponding Author: Tanji Hoshi, Department of Urban Science, Tokyo Metropolitan University, 192-0364 Minamioosawa 1-1 Hachiooji City, Tokyo, Japan.

Received: 06 November 2025; Accepted: 11 November 2025; Published: 17 December 2025

Citation: Tanji Hoshi. Long-Term Care for the Elderly is Determined by a Causal Link to Lifestyle, Three Health Factors Based on Socioeconomic Status. Journal of Women’s Health and Development. 8 (2025): 60-69.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Factors influencing the amount of long-term care needed by the elderly, which are more common in women than men, include lifestyle habits, physical, mental, and social health, as well as frailty and decreased exercise frequency. However, the causal relationships, including socioeconomic status as a background factor, remain unclear. In this study, the level of long-term care needs was designated as the dependent variable. A follow-up survey was conducted, utilizing educational background and annual income as underlying factors, to analyze physical, mental, and social health, along with the relationship between preferred diet and lifestyle habits such as exercise to clarify the underlying structure. The treatment status of cerebrovascular accidents will also be examined by sex. Methods: In September 2001, a mail-in survey was carried out among 16,462 elderly residents in the suburbs of Tokyo using a self-administered questionnaire. The cohort study evaluated the long-term care needs after three years for 8,162 individuals confirmed to be alive. The analysis method employed to explore the causal structure of care requirements was covariance structure analysis. Results: The study found that women had a significantly greater need for nursing care compared to men in older age groups. The level of long-term care needed after three years was only slightly affected by lifestyle habits, such as how often they exercised. However, the levels of mental, physical, and social health influenced by lifestyle habits were closely linked. Additionally, positive lifestyle habits and three health factors were influenced by advantageous socioeconomic factors. In other words, lifestyle habits like diet helped maintain the three health factors, reduced the number of diseases needing treatment, and ultimately prevented the need for long-term care. There were no sex differences in the overall relationship of the structure. In this survey, we were able to explain 45% of the variance in the coefficient of determination regarding the long-term care needed after 3 years. Conclusion: The amount of long-term care needed after three years was minimally influenced by socioeconomic factors and lifestyle choices as a direct result. The three health indicators remained the most important factors in preventing diseases, including cerebrovascular accidents, within the framework of socioeconomic status as a structural basis. Future research is likely to focus on the index of perception and cognitive functions related to health and aging, and the causal relationships are expected to become clearer through randomized intervention studies.

Keywords

Prevention of need for long-term care; Lifestyle including diet; Socioeconomic factors; Causal structure; Elderly

Prevention of need for long-term care articles; Lifestyle including diet articles; Socioeconomic factors articles; Causal structure articles; Elderly articles

Article Details

Background

In a country like Japan, where the population is aging rapidly, it is vital to focus not only on extending lifespan but also on reducing the need for extensive long-term care. Promoting healthy aging helps reduce the caregiving burden and stabilizes healthcare costs. The total annual cost for medical and long-term care insurance related to caregiving exceeds 15.7 trillion yen, making up about 15.3% of the national budget in 2020[1]. Therefore, maintaining a high quality of life and living comfortably without requiring long-term care is essential not only for individuals and their families but also for easing the financial burden on the entire country. In response to these challenges, Japan introduced the "Healthy Japan Plan 21 for Healthy Longevity" in 2000 [2]. The plan encourages promoting oral hygiene, supporting a balanced diet, and implementing measures to foster healthy lifestyle habits, including smoking cessation, to achieve good health and longevity. However, it does not address the significance of socio-economic factors.

Significant factors associated with maintaining survival have been reported [3-12]. Lifestyle habits, including how often people exercise, are key in predicting future survival outcomes [3]. Additionally, BADL (basic activities of daily living) and LIADL (instrumental activities of daily living) are identified as physical frailty factors that influence survival prognosis [4,5]. Other factors affecting survival include subjective health status and mental well-being, commonly referred to as life satisfaction. Studies show that the more individuals perceive their health and life satisfaction based on personal judgments, the more likely they are to sustain survival over time [6,7]. Social health has also been shown to contribute to survival [8,9]. Socioeconomic factors also play a crucial role in establishing a solid foundation for good health.

The annual income of older adults depends on the educational achievements from about 50 years ago. In our follow-up study of seniors, we found that higher yearly income was significantly linked to longer survival[10]. As a related factor in preventing the need for long-term care, Komeji et al. analyzed 532 elderly individuals who used home services and found that the level of need for long-term care was significantly associated with undernutrition, as indicated by lower BMI [11]. Based on previous research by Ng et al. [12] and Lorenzo et al. [13], lifestyle habits, including exercise frequency and dietary choices, influence long-term care needs. However, the exact cause-and-effect relationship is not fully clear, especially when considering background socioeconomic status and mental, physical, and social health. To ensure proper care levels and prevent treatable diseases such as cerebrovascular accidents, understanding the causal link between socioeconomic status and healthy lifestyle choices could help prioritize socioeconomic factors for targeted interventions. There are very few reports on such structural studies. One reason is that Germany, Japan, and South Korea are developed countries with long-term care insurance systems, and these are not universal systems worldwide.

It has been observed that women require more nursing care than men. Additionally, the gap between average life expectancy and the need for long-term care was 8.84 years for men and 12.35 years for women in 2016. Therefore, the amount of long-term care women need is a significant health issue. However, the actual status of nursing care needs by gender and related factors remains unclear. regarding the high level of nursing care women require, the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan reported that women exercise less frequently than men by a certain percentage. Additionally, factors such as cerebrovascular accidents, dementia, and frailty are linked to the need for long-term care[11,12,13]. However, the causal relationships, including socioeconomic factors affecting the connection between exercise frequency, cerebrovascular events, cognitive decline, and care needs later in life, have not been clearly established.

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the physical, mental, and social health of elderly individuals living in the suburbs of Tokyo, as well as their lifestyle habits that may influence the level of long-term care required three years later. It seeks to clarify the relationship between these factors and socioeconomic variables across genders. If the study's hypothesis is confirmed, it will help explain the importance of socioeconomic factors that underlie the three controllable aspects of health and lifestyle. In particular, this could aid efforts to prevent the need for long-term care from a gender perspective in an effective and systematic manner.

Materials and Methods

Research Subject

In September 2001, we conducted a questionnaire survey among all elderly individuals aged 65 and older living at home in suburban Tokyo, specifically in Tama City, Japan. Of the 16,462 eligible elderly individuals, 13,066 (79.4% response rate) provided informed consent to participate in the study and returned the self-administered questionnaire by mail. In September 2004, we mailed a second identical questionnaire to the respondents. A total of 8,558 participants responded (505 had moved, 914 were deceased, and 4,089 did not respond). We followed up with all participants until August 31, 2007. We analyzed 8,162 subjects, including 3,851 males and 4,311 females, aged 65 to 84 at the time of the first survey, who were able to determine their need for long-term care 3 years later.

Research Area

The city selected for this study partially developed as a commuter town to support the increasing number of workers and their families in the metropolitan Tokyo area from the 1970s to the 1990s, an era characterized by Japan's significant economic growth. Most residents were middle class, and the city’s total population was 145,862 as of 2000, with 11.1 percent of residents aged 65 or older.

The Questionnaire and Measures

Socioeconomic Status

Standardized questions were validated in these surveys to assess health status and lifestyle. In 2001, socioeconomic status was evaluated based on education level and annual income. Educational attainment was classified into three categories: high school graduates, junior college graduates, and those with degrees beyond college, as well as respondents who did not answer. Annual marital income levels were divided into four categories: less than one million Japanese yen (equivalent to less than US$6,667, with 1 US$ = 150 yen), less than three million yen, less than seven million yen, and more than seven million yen in 2001. We included educational background, annual marital income, age, and height as additional variables to analyze socioeconomic status. A certain amount of height growth signifies a prosperous and healthy childhood experience. Height has been shown to be a highly valid indicator of survival prognosis after about half a century [14, 15]. According to Jousilahti et al. [14], a follow-up study involving 31,199 adult residents in Eastern Finland tracked participants for 15 years, revealing that shorter height was linked to a higher overall mortality rate. Similarly, the survival duration of 13,460 older adults in our country’s suburbs is being monitored over three years. As a result, it was reported that the mortality rate of males with a BMI of less than 19 and females shorter than 150 cm was significantly higher than that of the taller group [15].

Lifestyle and Diet

Healthy lifestyle factors were identified as beneficial habits that were significantly associated with the number of survival days over 6 years. Our analyses indicated that the habits linked to increased survival days included daily alcohol consumption, never smoking (even in the past), sleeping less than 9 hours per night, exercising more than once a week, and maintaining a BMI greater than 20. We assessed these healthy lifestyle habits on a scale from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating a more advisable lifestyle [3]. Our analyses identified healthy dietary habits as follows: consuming meat, eggs, and blue-backed fish 1 to 4 days per week; eating soy foods, dairy products, and fruits more than 3 days a week; consuming vegetables more than 5 days a week; and having breakfast every day. Lastly, we calculated a dietary health score based on the consumption of the four recognized healthy food categories (three points for each type), ranging from 0 to 12, where a higher score indicates healthier nutritional habits [16].

Three Health Factors

The three health-related dimensions examined in our study included physical, mental, and social health components. Physical health parameters consisted of basic activities of daily living (BADL) [4] and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) [5]. Three questions assessed the BADL score: “Can you go to the toilet by yourself?” “Can you take a bath by yourself?” and “Can you walk outside?” Individuals received one point for each function they could perform, with overall scores ranging from 0 to 3, where higher scores indicated greater basic activity competence. The IADL score was measured through five questions related to instrumental activities: “Can you buy daily necessities by yourself?”, “Can you cook daily meals by yourself?”, “Can you deposit and withdraw money from a bank account?”, “Can you complete documents related to insurance and pensions?”, and “Can you read books and newspapers?” [5]. Since the IADL was scored similarly to the BADL, total scores ranged from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating a greater capability in instrumental activities. Mental health was self-reported as a subjective health measure in 2001. The question was, “Do you think you are healthy?” There were four choices: very healthy, moderately healthy, not so healthy, and not healthy [6]. The life satisfaction question was, “Are you satisfied with your daily life?” There were three choices: very satisfied, moderately satisfied, and unsatisfied. Scores ranged from 1 to 3 [7]. Social health was assessed by considering factors like going outdoors and communicating with neighbors. The question examined how often participants go outside: “How often do you go outside, including around your neighborhood?” Responses ranged from less than once a month to more than 3 to 4 times a week [8]. Communication within the neighborhood was measured by asking, “How often do you communicate with your friends or neighbors?” Scores ranged from seldom to once a month to 3 to 4 times a week and almost daily, using a scale from 1 to 4 [9].

Treated Diseases

The conditions most strongly associated with decreased survival after 6 years include hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, heart disease, and liver disease. Consequently, the score for the number of treated conditions ranges from 0 to 5 points.

Bedridden Status

The level of bedridden status was used to evaluate the health conditions of the elderly three years later. This evaluation employed a public tool developed by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The tool includes six levels, from the least severe (requiring mild support) to the most severe (needing comprehensive care and support). In our analysis, a respondent who received no care scored zero, a respondent at the least severe level scored one, and a respondent at the most severe level scored six. In this article, we refer to it as Bedridden Status, but it is considered synonymous with long-term care needs.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and AMOS Version 28.0 software (IBM, New York, USA). The relationships between categories were determined using the chi-square test or the Kendall τ test, and quantitative comparisons were performed using a one-way analysis of variance. To clarify the causal structure of the hypothetical model with latent variables, covariance structure analysis [17, 18] was employed. The latent variables used in the model were identified through exploratory factor analysis conducted with the varimax rotation method and the maximum likelihood estimation approach. In the causal structure analysis, the goodness-of-fit indices of the model included NFI (Normed Fit Index), IFI (Incremental Fit Index), and RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) [17, 18]. All estimates were standardized constants, and statistically significant differences were defined as those with a p-value of 5% or less.

Result

Target Audience

A total of 8,162 people were analyzed, including 3,851 men and 4,311 women.

|

Bedridden Status Three Years Later |

Total |

Bedridden Status Three Years Later |

Total |

||||

|

Non of Bed |

Bedridden |

Non of Bed |

Bedridden |

||||

|

Ridden status |

status |

Ridden status |

status |

||||

|

Men 65-74 |

2777 |

111 |

2888 |

Men 75-84 |

776 |

90 |

866 |

|

96.2% |

3.8% |

100.0% |

89.6% |

10.4% |

100.0% |

||

|

Women 65-74 |

2786 |

130 |

2916 |

Women 75-84 |

1027 |

208 |

1235 |

|

95.5% |

4.5% |

100.0% |

83.2% |

16.8% |

100.0% |

||

|

Total |

5563 |

241 |

5804 |

Total |

1803 |

298 |

2101 |

|

95.8% |

4.2% |

100.0% |

85.8% |

14.2% |

100.0% |

||

|

χ2=1,38 P=0.134 |

χ2=17.39 P<0.001 |

||||||

Table 1: Bedridden status by age and sex.

The proportion of nursing care needed was compared by gender and age in the 65-74 age group and the 75-84 age group. The results showed that women had a significantly higher proportion of long-term care needs than men among the late elderly (Table 1).

|

Men |

Women |

||||||

|

None of Bed |

Bedridden |

None of Bed |

Bedridden |

||||

|

Ridden status |

status |

P |

Ridden status |

status |

P |

||

|

Educational Background |

Graduated from senior high school |

819(92.6%) |

65( 7.4%) |

-0.034 |

1,761(89.7%) |

203(10.3%) |

-0.091 |

|

Graduated from vocational school |

1,121(96.0%) |

47( 4.0%) |

P=0.046 |

1,523(95.2%) |

76( 4.8%) |

P<0.001 |

|

|

Graduated from college |

1,403(95.2%) |

71( 4.8%) |

218(93.2%) |

16( 6.8%) |

|||

|

Yealy Income |

< 1 million yen |

72(93.5%) |

5( 6.5%) |

347(86.8%) |

53(13.3%) |

||

|

1 milion-3 million yen |

1,064(92.4%) |

88( 7.6%) |

-0.082 |

1,456(91.1%) |

142( 8.9%) |

-0.084 |

|

|

3 milion-7milion yen |

1,759(96.0%) |

73( 4.0%) |

P<0.001 |

1,232(94.8%) |

67( 5.2%) |

P<0.001 |

|

|

>7million yen |

382(97.7%) |

9( 2.3%) |

200(93.5%) |

14( 6.5%) |

|||

|

Communication with |

seldom |

1,066(91.3%) |

102( 8.7%) |

727(84.2%) |

136(15.8%) |

||

|

the Neighbours |

once a month |

872(97.1%) |

26( 2.9%) |

-0.111 |

733(92.7%) |

58( 7.3%) |

-0.125 |

|

three or four a week |

1,029(96.3%) |

40( 3.7%) |

P<0.001 |

1,540(94.8%) |

85( 5.2%) |

P<0.001 |

|

|

almost every day |

461(93.3%) |

8( 1.7%) |

563(95.1%) |

29( 4.9%) |

|||

|

Going Outside |

less than once a month |

95(73.1%) |

35(26.9%) |

108(65.5%) |

57(34.5%) |

||

|

more than once a month |

202(86.3%) |

32(13.7%) |

-0.208 |

249(83.0%) |

51(17.0%) |

-0.216 |

|

|

more than three or four a week |

3,163(96.5%) |

114( 3.5%) |

P<0.001 |

3,245(94.3%) |

195( 5.7%) |

P<0.001 |

|

|

Subjective Health |

unhealthy |

99(63.9)%) |

56(36.1%) |

139(65.6%) |

73(34.4%) |

||

|

not so healthy |

369(89.3%) |

44(10.7%) |

-0.184 |

491(80.6%) |

118(19.4%) |

-0.247 |

|

|

almost healthy |

2,415(96.8%) |

81( 3.2%) |

P<0.001 |

2,595(95.1%) |

135( 4.9%) |

P<0.001 |

|

|

very healthy |

649(97.4%) |

17( 2.6%) |

555(98.4%) |

9( 1.6%) |

|||

|

Life Satisfaction |

not satisfied |

307(86.7%) |

47(13.3%) |

270(84.4%) |

50(15.6%) |

||

|

moderately satisfied |

715(93.2%) |

52( 6.8%) |

-0.116 |

838(87.5%) |

120(12.5%) |

-0.137 |

|

|

satisfied |

2,439(96.4%) |

91( 3.6%) |

P<0.001 |

2,588(94.7%) |

145( 5.3%) |

P<0.001 |

|

|

ADL |

2.93(0.25) |

2.51(0.89) |

P<0.001 |

2.90(0.31) |

2.61(0.76) |

P<0.001 |

|

|

IADL |

4.80(0.59) |

3.05(1.94) |

P<0.001 |

4.86(0.56) |

3.40(1.83) |

P<0.001 |

|

|

Treated Diseases |

0.62(0.77) |

1.03(0.99) |

P<0.001 |

0.52(0.70) |

0.93(0.91) |

P<0.001 |

|

|

Diet Scores |

3.95(2.38) |

3.16(2.63) |

P<0.001 |

4.58(2.31) |

3.72(2.39) |

P<0.001 |

|

|

Lifestyle |

2.92(1.11) |

1.841(1.17) |

P<0.001 |

2.88(1.01) |

2.31(0.98) |

P<0.001 |

|

|

Age |

70.71(4.74) |

74.12(5.94) |

P<0.001 |

71.29(4.97) |

75.79(5.39) |

P<0.001 |

|

|

Height |

163.79(6,72) |

162.44(6,72) |

P<0.001 |

151.10(6,39) |

148.83(8.64) |

P<0.001 |

|

|

( )Standardized deviation |

|||||||

Table 2: The Relationships between the Bedridden Status Three Years Later and Correlational Observed Factors by Sexes.

Relationship Between the Degree of Need for Long-Term Care and Each Explanatory Factor After 3 Years, Gender

The need for long-term care after three years was significantly related to all 13 explanatory factors in this study. In other words, higher annual income and greater height, along with more favorable conditions in the other 11 factors, were associated with a noticeably lower level of nursing care needed after three years. These relationships were also observed for gender. However, the one-way ANOVA showed that as the educational level exceeds college, the required amount of long-term care increases for both men and women compared to those with lower education. Additionally, women needed significantly more long-term care than individuals earning less than 1 million yen, especially in the group earning 7 million yen or more. We also identified the factors most closely linked to the need for long-term care at the three-year mark and examined the causal relationships among the 13 items using covariance analysis.

Causal Structure Based on Each Explanatory Factor That Defines the Need for Long-term Care After 3 Years

Search for Latent Variables in Covariance Structure Analysis Using Factor Analysis

In this analysis, we performed an exploratory factor analysis with the maximum likelihood method and Promax oblique rotation (Table 3). The factor analysis revealed that the first factor represents "socioeconomic status" and includes educational attainment, annual marital income, age, and height, classifying these variables as latent factors. The second factor relates to subjective health and disease treatment. Lifestyle and diet scores are termed "lifestyle and diet scores." IADL, BADL, going outside, and contact with neighbors are grouped into three health-related factors, along with life satisfaction. The combined squared loadings of these factors account for 32.4%. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for "socioeconomic status" is 0.084, and for "Lifestyle Score and Diet Score," it is 0.32 (Table 3).

|

Socioeconomic Status |

Treated Diseases |

Physical Health |

Lifestyle and Diet Scores |

|

|

Educational Background |

.736 |

.011 |

.029 |

-.030 |

|

Height(cm) |

.527 |

.037 |

.017 |

-.118 |

|

Ages |

-.429 |

-.025 |

-.141 |

-.055 |

|

Yearly Income |

.406 |

.033 |

.009 |

.181 |

|

Subjective Health |

.132 |

.958 |

.113 |

.225 |

|

Treated Diseases |

.003 |

-.288 |

-.127 |

-.097 |

|

IADL |

.079 |

.194 |

.803 |

.213 |

|

BADL |

.059 |

.068 |

.415 |

.051 |

|

Contact with the Neighbours |

-.032 |

.100 |

.052 |

.529 |

|

Going Outside |

.107 |

.095 |

.293 |

.377 |

|

Life Satisfaction |

.032 |

.278 |

.053 |

.344 |

|

Lifestyle |

.182 |

.109 |

.108 |

.312 |

|

Diet Scores |

-.023 |

.032 |

.030 |

.209 |

|

Cronbach’s alpha |

0.084 |

-0.84 |

0.42 |

0.32 |

Table 3: Results of exploratory factor analysis.

Structure of Related Factors Determining the Level of Long-Term Care Needs

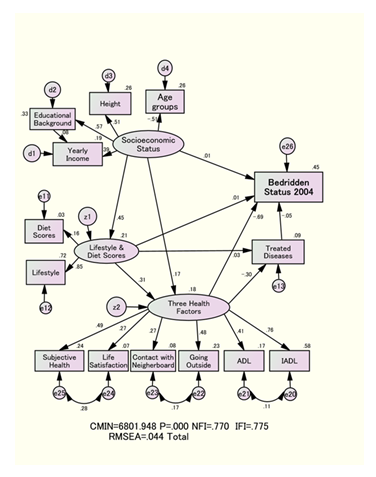

Based on hypothetical models derived from latent variables identified through exploratory factor analysis, the best-fitting model was selected according to the modified index. The fit indices were NFI = 0.770, IFI = 0.775, and RMSEA = 0.044, as shown in Fig. 1. This method demonstrated strong compatibility and was chosen as the final structure diagram of associations, supported by the literature [17,18].

The ellipse represents the latent variable, the rectangle indicates the observed variable, and the circle is an error variable. Each number shown by an arrow indicates a standardized estimate. We also examined items related to "Socioeconomic Status" ("" means latent variable), "Lifestyle and Diet Scores," and "Three Health Factors," which means each survey item could serve as both a cause and a consequence. To clarify the causal relationship, we examined the direction and strength of the relationship across all possible combinations of variables. We analyzed each combination and chose the one with the highest standardized estimate. Consequently, "Socioeconomic Status," "Three Health Factors," and "Lifestyle and Diet Scores" were identified as explanatory latent variables. At the same time, [bedridden Status] ([ ] means observed variable) was designated as the dependent observed variable after three years.

The standardized coefficients significantly affected all latent variables. Furthermore, the combined effects of direct and indirect relationships were assessed together. Additionally, all links between latent and observed variables were statistically significant in the Wald test.

Causal Structure of Explanatory Factors for the Degree of Long-term Care Needed

The comprehensive analysis in Figure 1 shows that the strongest overall impact on [Bedridden Status in 2004] came from the recommended combination of "Three Health Factors" and a "Lifestyle and Diet Score" based on "Socioeconomic Status." Additionally, the direct effect of the "Three Health Factors" on [Bedridden Status in 2004] is -0.69, which accounts for 45% of the factors influencing the level of long-term care needed.

Direct effects of “socioeconomic factors" and "lifestyle and diet score" on the Degree of Need for Long-term Care

The direct effect of "socioeconomic status" on "lifestyle and diet score" was 0.45. The coefficient of determination of the "lifestyle and diet score is 21%. The direct effect on the need for long-term care after 3 years, as measured by the "lifestyle and diet score," was 0.01 (Table 4). It is clear that "Socioeconomic Status" and "Lifestyle and Diet Score" do not directly influence [Bedridden Status].

Total Effect of Each Explanatory Factor on the Degree of Need for Long-term Care

The combined effect of the "three health factors" on the need for long-term care was the most significant, at -0.69. The total effect of the "lifestyle and diet score" on the need for long-term care was recorded at -0.21. Similarly, the total effect of "socioeconomic status" was -0.21 (Table 4). A negative standardized estimate indicates a decreased level of care needed.

The indirect effect of "Socioeconomic Status" on the "Three Health Factors" through "Lifestyle and Diet Score" was 0.14 (0.45×0.31). 18% of the "Three Health Factors" were explained (Figure 1).

|

Men |

Women |

Total |

||

|

“Socioeconomic Status”⇒⌈Bedridden Status⌋ |

0.08 |

-0.03 |

0.01 |

|

|

“Socioeconomic Status ”⇒"Three Health Factors” |

0.04 |

0.18 |

0.18 |

|

|

“Socioeconomic Status ”⇒“Lifestyle and Diet Scores” |

0.51 |

0.59 |

0.45 |

|

|

Standardized |

“Lifestyle and Diet Scorse”⇒⌈Bedridden Status⌋ |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

|

Direct Effect |

“Lifestyle and Diet Scores ”⇒“Three Health Factors” |

0.48 |

0.36 |

0.31 |

|

“Lifestyle and Diet Scores”⇒⌈Treated Diseases⌋ |

0.10 |

0.02 |

0.01 |

|

|

“Three Health Factors”⇒⌈Bedridden Status⌋ |

-0.74 |

-0.66 |

-0.69 |

|

|

“Three Health Factors”⇒⌈Treated Diseases⌋ |

-0.40 |

-0.26 |

-0.30 |

|

|

⌈Treated Diseases⌋⇒⌈Bedridden Status⌋ |

-0.11 |

-0.02 |

-0.05 |

|

|

“Socioeconomic Status”⇒⇒“Three Health Factors” |

0.28 |

0.36 |

0.32 |

|

|

“Socioeconomic Status”⇒⇒⌈Treated Diseases⌋ |

-0.06 |

-0.08 |

-0.08 |

|

|

Standardized |

“Socioeconomic Status”⇒⇒⌈Bedridden Status⌋ |

-0.13 |

-0.65 |

-0.21 |

|

Total Effect |

“Lifestyle and Diet scores”⇒⇒⌈Treated Diseases⌋ |

-0.10 |

-0.08 |

-0.20 |

|

“Three Health Factors”⇒⇒⌈Bedridden Status⌋ |

-0.70 |

-0.65 |

-0.69 |

|

|

“Lifestyle and Diet scores”⇒⇒⌈Bedridden Status⌋ |

-0.35 |

-0.22 |

-0.21 |

|

|

“” : Latent variable◟⌈⌋: Observed variable◟ ⇒: Direct Effect◟⇒⇒:Total Effect |

||||

Table 4: Direct and total effect on [Bedridden Status] by “Three Health Factors” and “Socioeconomic Status” by sex.

Gender differences in the need for long-term care

The need for nursing care was higher among women than men over 75 years old. However, there was no significant gender difference in the impact of the 13 items used to assess the need for long-term care.

Discussion

Causal Relationship on the Degree of Need for Nursing Care

This study revealed, for the first time worldwide, that socioeconomic factors are a primary and fundamental influence on long-term care needs. Lifestyle and health factors, including diet, supported by advantageous socioeconomic conditions, played a significant role in this context. Instead of directly determining the necessary level of care through regular exercise and nutrition, the study showed indirect effects by maintaining three key health indicators while simultaneously lowering the number of diseases requiring treatment. Favorable socioeconomic conditions create a strong foundation, and maintaining healthy lifestyle habits leads to better health outcomes. This can help reduce the need for long-term care by decreasing the occurrence of cerebrovascular accidents. The coefficient for determining the need for long-term care after three years was 45% (Figure 1).

To reduce the level of care needed, it is crucial to address the underlying socioeconomic factors across multiple family generations, ensure a sufficient food supply, and encourage healthy lifestyle choices that positively impact health. Additionally, it is essential to foster physical, mental, and social well-being.

It is estimated that maintaining the survival rate across generations of children, due to high family stature, is influenced not only by the excellent genetics of the parents but also by the desired growth trajectory after birth [14,15]. The influence of parents after birth is often referred to as a "meme." While genetic factors are beyond our control, memes can be managed, and family support after birth should also be recognized as a vital part of family education. Future research is expected to clarify the external validity of this study, not only for reproducibility but also through intervention studies focused on the recommended family socioeconomic status.

The Importance of Lifestyle Habits and Three Health Factors to Prevent the Need for Long-term Care

It was reported that a low BMI, considered an indicator of undernutrition, is linked to the survival days [15]. The study by Komeji et al.[11] was supported by follow-up research, as mentioned in this article.

It has been reported that dementia increases the need for long-term care. However, this survey did not include a highly reliable measure, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), which is used to diagnose cognitive function medically. When we examined and analyzed IADL, which is linked to cognitive function, it became clear that it is a significant factor in determining the need for long-term care after three years. Future research should systematically investigate cognitive function, such as an MMSE [19].

It has been confirmed that the desirability of education, a socioeconomic factor, contributes to a couple's income and their ability to support daily life, which in turn improves the three health factors and ultimately helps prevent caregiving. Socioeconomic factors such as age, height, and educational background are difficult to control. In comparison, annual income is the most controllable factor [10]. Follow-up studies of older adults have shown that higher yearly income, supported by education, is associated with longer survival times. However, there is a limit to this relationship. Specifically, once the yearly family income of an elderly couple reaches 4.5 million yen, no additional benefits are observed. The income threshold for elderly individuals living in rural areas is 2.5 million yen [10].

Our cohort study found that the primary factor influencing survival days was the patient's recommended socioeconomic status, particularly access to a family dentist. Additionally, socioeconomic factors are key drivers that affect the reduction of treatable diseases through lifestyle choices and help maintain mental, physical, and social well-being. Choosing only a family dentist instead of a family physician was significantly linked to longer survival[19]. We can estimate that similar results might occur if the dependent variable is the level of nursing care instead of the number of days alive.

In this study, we focus solely on the causal structural effect on the level of care needed after 3 years. Future research is expected to examine the "three health factors," "socioeconomic status," and "life score/diet score" at different times to better understand the actual causal structure rather than just the associated structure.

Additionally, randomly selecting subjects is crucial for enhancing the external validity of research findings and ensuring reproducibility. There are also challenges concerning survey indicators. All explanatory factors, except for the level of long-term care needs, rely on self-reports. In future surveys, the indicators to be evaluated are expected to include examining the causal relationship between the level of long-term care needs and objective indicators obtained from medical examinations. Moreover, to improve the determination coefficient of the degree of long-term care required, which is a dependent variable, it is important to clarify not only the frequency of exercise but also its intensity and duration. Schlitzer et al. studied 1,485 patients admitted to acute geriatric units in Germany, including those with MMSE scores, and reported that daytime sleepiness was associated with in-hospital falls among elderly patients [20]. This study found that survival rates were significantly lower in the group that slept more than 9 hours. Therefore, we focused on sleep durations of less than 9 hours as a preferred lifestyle choice. In the future, it was suggested that drowsiness could be added as a new survey item to help improve the determination coefficient of dependent variables.

Sapporo et al. [21] conducted intervention studies focused on the subjective health of older adults in the community. Their results showed that health education interventions aimed at improving subjective health over 18 months were more effective at preventing institutional admissions and deaths than those in the control group. Therefore, future practical support for preventing long-term care needs in older adults should emphasize the importance of maintaining subjective health. However, it should be recognized that maintaining subjective health is influenced by positive lifestyle habits, which are in turn affected by socioeconomic factors.

According to the community program recommended by the WHO, the program should include various supportive elements, such as a living environment that encourages physical activity, promotes healthy eating habits, fosters psychological well-being, and facilitates social engagement, taking into account socioeconomic status [22].

Additionally, this survey does not examine perceptions of aging and health awareness, which have been reported in previous studies, as shown below [23-25]. Shirai et al. found that maintaining a positive outlook is linked to a lower risk of requiring long-term care [23]. Major previous studies have mainly focused on scales related to the significance of aging, demonstrating predictive validity for survival and life satisfaction, as noted by Tully-Wilson et al. [24]. A positive attitude toward retirement is also connected to better survival rates [25]. Including questions about perceptions of aging and health awareness in future surveys is likely to boost the coefficient of determination for the three health factors, as well as lifestyle habits, and ultimately, the coefficient of determination for bedridden status could increase by more than 45%.

This analysis indicated that late-stage elderly women need more long-term care. However, there were no gender differences in the main factors that influence the amount of care required. The main reason might be a genetic factor that allows women to live longer than men, but this is a topic for future research. Moving forward, it is anticipated that randomized intervention studies using objective health indicators will help clarify the causal relationship behind preventing the need for long-term care. This is because no intervention studies have yet reported establishing a control group based on the level of care needed. The dependent variable in this study was the need for long-term care. In future research, we should examine not only the need for long-term care but also healthy longevity, including the duration of individual survival.

Conclusion

The amount of long-term care required after three years was minimally influenced by socioeconomic factors and lifestyle choices directly. The three health indicators remained the most significant factors in preventing diseases, including cerebrovascular accidents, within the context of socioeconomic status as a structural foundation. Future research is likely to incorporate the index of perception and cognitive functions related to health and aging, and the causal relationships are expected to become clearer through randomized intervention studies.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The Tama city local government and Tokyo Metropolitan University signed an agreement to protect privacy and confidentiality. Here, mutual secrecy is strictly enforced. All analysis data are identified by ID only. On September 16, 2000, I completed an ethics review conducted by the Faculty Association of the Institute of Urban Sciences at Tokyo Metropolitan University and received permission to conduct our research.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the study design, data analysis, or interpretation.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (Hone0-Health-042) and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (No.15 31012 and 14350327). We also appreciate the financial support received from Mitsubishi Foundation (2009-21) in 2009.

Authors'` Contributions

T.H. summarized the entire sentence. The author has read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors express particular gratitude to all the survey participants in Tama city, Tokyo, Japan.

Authors' Information

The first author, Tanji Hoshi (MD, Ph.D.), graduated from Fukushima Prefectural Medical University in 1978 and earned a Ph.D. from the Department of Public Health at the University of Tokyo in 1987. I dedicated my career to education, research, and practice in preventive medicine and public health. After working at the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and the National Health Research Institute, I became a professor at Tokyo Metropolitan University. I worked there for 15 years and have mentored 31 Ph.D. students. The total number of 24 students earning a Ph.D. in philosophy has been the highest at our university.

Trial Registration Data

The analytical data from this study are available from the UMIN SYSTEM in Japan as an open-access system (https://upload.umin.ac.jp/cgi-bin/fileshare/upload.cgi?DELETE=1&on=589518, Accessed October 31, 2025). Personal registration is required for data specifications.

Additionally, analytical data and materials can be obtained from the first author via the following email address: star@onyx.dti.ne.jp (T. Hoshi, first author, star@onyx.dti.ne.jp)

References

- Labor Statistics Association. Trends in National Hygiene. 67 (2020/21): 11-21.

- Sakurai N, Hoshi T. The Aim of Health Japan 21. Hokennokagaku 45 (2003): 552-557.

- Berkman LF. Health and Ways of Living: The Alameda County Study. Oxford: Oxford University Press (1983).

- Branch LG, Katz S, Kniepmann K, et al. A Prospective Study of Functional Status among Community Elders. Am J Public Health 74 (1984): 266-268.

- Koyano W, Shibata H, Nakazato K, et al. Measurement of Competence: Reliability and Validity of the TMIG Index of Competence. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 13 (1991): 103-116.

- Kaplan GA, Camacho T. Perceived Health and Mortality: A Nine-Year Follow-Up of the Human Population Laboratory Cohort. Am J Epidemiol 117 (1983): 292-304.

- Rosella LC, Fu L, Buajitti E, et al. Death and Chronic Disease Risk Associated with Poor Life Satisfaction: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol 188 (2019): 323-331.

- Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social Networks, Host Resistance, and Mortality: A Nine-Year Follow-Up Study of Alameda County Residents. Am J Epidemiol 109 (1979): 186-204.

- Seeman TE, Kaplan GA, Knudsen L, et al. Social Network Ties and Mortality among the Elderly in the Alameda County Study. Am J Epidemiol 126 (1987): 714-723.

- Hoshi T. Causal Structure for the Healthy Longevity Based on the Socioeconomic Status, Healthy Diet and Lifestyle, and Three Health Dimensions, in Japan. In: Garg BS, editor. Health Promotion - Principles and Approaches. Intech Open (2023): 49-67.

- Komeji Y, Sugiyama M, Enoki H, et al. Analysis of Undernutrition and Factors in the Elderly Using Home Services. J Japan Soc Health Nutr Syst 2 (2016): 20-27.

- Ng TP, Feng L, Nyunt MSZ, et al. Nutritional, Physical, Cognitive, and Combination Interventions and Frailty Reversal among Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Med 128 (2015): 1225-1236.

- Lorenzo-López L, Maseda A, de Labra C, et al. Nutritional Determinants of Frailty in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. BMC Geriatr 17 (2017): 108.

- Jousilahti P, Tuomilehto J, Vartiainen E, et al. Relation of Adult Height to Cause-Specific and Total Mortality: A Prospective Follow-Up Study of 31,199 Middle-Aged Men and Women in Finland. Am J Epidemiol 151 (2000): 1112-1120.

- Hoshi T, Nakayama N, Takagi T, et al. Relationship between Height and BMI Classification of Elderly People Living at Home in Urban Suburbs. J Japan Soc Health Educ 18 (2010): 268-277.

- Kodama S, Hoshi T, Kurimori S. Decline in Independence after Three Years and Its Association with Dietary Patterns and IADL-Related Factors in Community-Dwelling Older People: An Analysis by Age, Stage, and Sex. BMC Geriatr 21 (2021): 1-17.

- Finkel SE. Causal Analysis with Panel Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications (1995).

- Bentler PM, Dudgeon P. Covariance Structure Analysis: Statistical Practice, Theory, and Directions. Annu Rev Psychol 47 (1996): 563-592.

- Hoshi T. Causal Factors Involving Family Physicians and/or Dentists that Affect the Six-Year Survival of Elderly Individuals. J Women’s Health Dev 8 (2025): 51-59.

- Schlitzer J, Friedhoff M, Nickel B, et al. Observed Daytime Sleepiness in In-Hospital Geriatric Patients and Risk of Falls. Z Gerontol Geriatr 56 (2023): 545-550.

- Shapiro A, Taylor M. Effects of a Community-Based Early Intervention Program on the Subjective Well-Being, Institutionalization, and Mortality of Low-Income Elders. Gerontologist 42 (2002): 334-341.

- World Health Organization. Integrated Care for Older People: Guidelines on Community-Level Interventions to Manage Declines in Intrinsic Capacity. World Health Organization (2017): 46.

- Shirai M. Analyzing the Differences in Positive Thinking between the Healthy Elderly and the Elderly with Long-Term Care Risk. Jpn J Public Health 66 (2019): 88-95.

- Tully-Wilson C, Bojack R, Millear PM, et al. Self-Perceptions of Aging: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Psychol Aging 36 (2021): 773-789.

- Reuben N, Heather GA, Joan KM, et al. Retirement as Meaningful: Positive Retirement Stereotypes Associated with Longevity. J Soc Issues 72 (2016): 69-85.