Genetic Engineering and MicroRNAs: Comparative Genomic Analysis of Brain Tumors and Neurodevelopmental Diseases

Article Information

Shivi Kumar1*, Teryn Mitchell2, Daniel Mehta3

1University of Pennsylvania, Mind Matters Foundation, USA

2PhD Columbia University, USA

3PhD University of California Los Angeles, USA

*Corresponding authors: Shivi Kumar, University of Pennsylvnia, Mind Matters Foundation, USA.

Received: 04 January 2026; Accepted: 07 January 2026; Published: 02 February 2026

Citation: Shivi Kumar, Teryn Mitchell, Daniel Mehta. Genetic Engineering and MicroRNAs: Comparative Genomic Analysis of Brain Tumors and Neurodevelopmental Diseases. Journal of Biotechnology and Biomedicine. 9 (2026): 05-19

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

This research investigates the genetic mutations and underprints of brain tumors and cancers, and provides an in-depth review of the pathophysiology and pathways across the different tumors and diseases. As well as that, This literature review embarks on an intricate journey to dissect and synthesize the elaborate genetic landscapes that typify brain tumors—namely glioblastoma, meningioma, and medulloblastoma—and autism, a defining condition in the spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders. Central to this exploration are microRNAs (miRNAs), diminutive yet potent non-coding RNA molecules that have surged to prominence as quintessential regulators of gene expression. Their pervasive influence spans a multitude of biological processes and pathways, crucially impacting both oncogenesis and neurodevelopment. Originating in the early 1990s, the discovery of miRNAs marked a paradigm shift in our understanding of gene regulation, unveiling a layer of complexity that intricately governs cellular fate, differentiation, and proliferation. These small RNA sequences, typically about 22 nucleotides in length, act as post-transcriptional regulators that either degrade target mRNA or inhibit its translation, thereby modulating gene expression in a manner that is both subtle and profound. The functional implications of miRNAs in a diverse array of diseases have underscored their potential as biomarkers for diagnosis. We aim to facilitate the development of personalized medicine approaches, promising more targeted and efficacious treatment paradigms. This encompasses the integration of genomic insights with clinical strategies, spotlighting the emergence of novel therapeutic candidates and the refinement of existing treatments. Simultaneously, the advent of genetic engineering technologies, with CRISPR-Cas9 at the forefront, has revolutionized our capacity to edit the genome with unparalleled precision, efficiency, and flexibility. Originating from a naturally occurring genome editing system in bacteria, CRISPR-Cas9 has been adapted into a powerful tool that allows for the targeted modification of DNA in living organisms. This technique's ability to precisely alter genetic sequences paves the way for groundbreaking advancements in disease modeling, functional genomic studies, and the development of targeted therapeutics, heralding a new era in medical science where genetic disorders can be corrected at their source. Our review delves deep into the role of miRNAs within the complex interplay of cellular growth and differentiation, illuminating their dual implications in the uncontrolled cellular proliferation characteristic of brain tumors and the dysregulated neurodevelopment associated with autism. Through a rigorous comparative genetic analysis, this study aspires to unveil shared genetic mutations and miRNA expressions bridging these conditions. This review not only amplifies comprehension of the genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in play but also highlights the potential to harness these insights for diagnostic and therapeutic breakthroughs. The frontier of genetic engineering and specific cases of alterations of gene editing is reviewed, as well as the potential of CRISPR-Cas9 neurodegenerative disease, brain tumor type, the use of tumor detection, and neuropathology of the tumors. Special attention is given to the evolutionary perspective on genomics, tracing the milestones in genomic research that have led to our current understanding. A pivotal section of the review is dedicated to comparative genomic analysis. This involves identifying and discussing common genetic mutations and pathways across different diseases, analyzing shared protein expressions, and their implications. The role of genetic engineering and gene editing is critically evaluated, encompassing the principles, advancements, and applications in brain tumors and neurodegenerative diseases. The frontier of genetic engineering and gene editing is explored, especially its potential in treating identified mutations. The transformative potential of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology is highlighted, emphasizing its role in precision medicine and the development of personalized treatment strategies.This includes an exploration of genetic engineering and gene editing techniques, as well as a discussion on the feasibility and challenges in applying these techniques. The review also delves into innovative therapeutic approaches and drug development, highlighting the development of new treatments based on genomic insights and case studies of drug development. In examining case studies and clinical implications, the review analyzes real-world applications and outcomes, discussing how these findings impact current and future treatment paradigms. The discussion synthesizes findings, integrating insights from genomic analysis and genetic engineering prospects, and reflects on the broader implications for research and practice.The conclusion provides a summation of key discoveries and a concise summary of the main findings and their significance. It also reflects on the study's contributions to the field and its potential impact. Finally, the review identifies emerging trends, unsolved questions, and discusses advancements in genomic research and genetic engineering, projecting the future trajectory of the field. This extensive literature review aims to be a cornerstone contribution to the fields of neurogenetics and neuro-oncology, inspiring further research and innovation, and paving the way for more targeted and effective therapeutic strategies in the future.

Keywords

Neurodegenerative Diseases; Brain Tumors; Autism Spectrum Disorder; Genetic Engineering; Bioinformatics; Genetic Sequencing; CRISPR-Cas9; Precision Medicine; Tumor Detection; Neuropathology; Glioblastoma Multiforme; Meningioma; Medulloblastoma; Pituitary Adenoma

Article Details

Introduction

Foundations of Genetic Engineering and Neurogenomics

Neurogenomics, an emerging field in biomedical research, presents a promising opportunity to revolutionize the understanding. It involves the study of the genetic and genomic factors that influence the nervous system's function, development, and diseases. By integrating neuroscience, genomics, and bioinformatics, neurogenomics aims to uncover how various genes, non-coding elements, and environmental factors interact to modulate neurological conditions within diverse populations. In the context of diagnosing patients and detecting tumors, neurogenomics has the potential to transform clinical practice by providing a deeper insight into the genetic underpinnings of neurological diseases. Traditional diagnostic methods reliant primarily on observable symptoms often present challenges, including the risk of misdiagnosis due to overlapping clinical presentations. Neurogenomic tools can enhance the specificity and timeliness of clinical diagnosis by identifying novel, clinically-relevant disease biomarkers specific to individual populations, thus reducing the chances of false positives. Furthermore, the development and application of neurogenomic tools can significantly impact tumor detection. One specific tool used is the mathematical programming and modeling performed by Computational Neuroscience.By identifying unique genetic variations associated with certain brain tumors, neurogenomics may enable clinicians to diagnose and stratify patients more accurately, leading to more targeted and effective treatment strategies.The integration of neurogenomics in clinical practice holds the potential to improve the accuracy of diagnosing patients with neurological diseases and enhance the detection and characterization of brain tumors, paving the way for more precise and personalized treatment approaches. The remarkable journey of these genomic studies into the era of rapid and accessible whole-genome sequencing, it became increasingly clear that the vast array of genetic information unlocked by these technologies holds the key to unraveling the complexities of the human brain and neurological diseases. Genome engineering using programmable nucleases facilitates the introduction of genetic alterations at specific genomic sites in various cell types. TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9, has been instrumental in creating genetically tractable models of brain tumors, derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which bear clinical relevance to glioblastomas, medulloblastomas, and atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors. These engineered models recapitulate the transcriptomic signature of each molecular subtype, enabling a better understanding of tumorigenesis and offering a platform for therapeutic discovery. Additionally, these models, studied in the context of three-dimensional cerebral organoids, have facilitated the study of tumor invasion and therapeutic responses. Neural progenitor cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) engineered with different combinations of genetic driver mutations observed in distinct molecular subtypes of glioblastomas give rise to brain tumors when engrafted orthotopically in mice.These engineered brain tumor models recapitulate the transcriptomic signature of each molecular subtype and authentically resemble the pathobiology of glioblastoma, including inter- and intra-tumor heterogeneity, chromosomal aberrations, and extrachromosomal DNA amplifications.Similar engineering with genetic mutations found in medulloblastoma and atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors in iPSCs have led to genetically trackable models that bear clinical relevance to these pediatric brain tumors. These models have contributed to an improved comprehension of the genetic causation of tumorigenesis and offered a novel platform for therapeutic discovery. Studied in the context of three-dimensional cerebral organoids, these models have aided in the study of tumor invasion as well as therapeutic responses.

Background of Brain Tumors

Cellular Origin and Classification

Brain tumors can originate from any cell type within the CNS, including neurons, glial cells (such as astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and ependymal cells), meningeal cells, and precursor cells. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies brain tumors based on their presumed cell of origin and histopathological characteristics, with grades I to IV reflecting increasing levels of malignancy, from benign to highly aggressive tumors. This classification facilitates prognosis estimation and treatment planning, highlighting the importance of precise histological and molecular diagnostics.

Oncogenesis: Genetic and Epigenetic Landscapes

The oncogenesis of brain tumors involves a complex interplay of genetic mutations, chromosomal abnormalities, and epigenetic modifications that disrupt normal cellular functions and pathways. Key processes affected include cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, DNA repair mechanisms, and cell signaling pathways such as RTK/RAS/PI3K, p53, and RB.

- • Genetic Alterations: Mutations in tumor suppressor genes (e.g., TP53, PTEN) and oncogenes (e.g., EGFR, MYC) are common in brain tumors and contribute to uncontrolled cell proliferation and survival. For example, mutations in the IDH1 and IDH2 genes are characteristic of lower-grade gliomas and secondary glioblastomas, affecting cellular metabolism and contributing to the neoplastic phenotype.

- • Epigenetic Modifications: Aberrant DNA methylation, histone modifications, and dysregulation of non-coding RNAs, including miRNAs, influence gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. These epigenetic changes can silence tumor suppressor genes or activate oncogenes, playing a critical role in brain tumor development and progression.

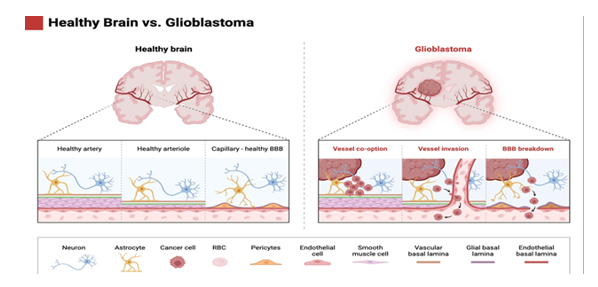

Tumor Microenvironment and Angiogenesis

The tumor microenvironment (TME) in brain tumors consists of cancer cells, surrounding blood vessels, immune cells, and the extracellular matrix (ECM), forming a complex and dynamic network that influences tumor growth, invasion, and therapeutic resistance. Angiogenesis, the process of new blood vessel formation, is a hallmark of malignant brain tumors, especially glioblastoma. Tumor cells secrete pro-angiogenic factors (e.g., VEGF) that promote vascular permeability and endothelial cell proliferation, ensuring an adequate supply of nutrients and oxygen to rapidly growing tumors.

Brain Tumor Stem Cells

Brain tumor stem cells (BTSCs) are a subpopulation of cells within tumors that possess the ability to self-renew and differentiate into various cell types found in the tumor. BTSCs are thought to play a key role in tumorigenesis, recurrence, and resistance to conventional therapies. Targeting BTSCs, along with the bulk tumor cells, is considered a promising strategy for improving treatment outcomes.

Fundamentals and Functional Dynamics of MicroRNAs: Biological Roles

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small, non-coding RNA molecules, approximately 22 nucleotides in length, that play a crucial role in regulating gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. First discovered in the early 1990s, miRNAs have since been recognized as pivotal components of cellular regulation, influencing a wide array of biological processes across various organisms. Their fundamental role in gene expression and the precision with which they modulate biological systems underscore their significance in health and disease. The biogenesis of miRNAs is a multi-step process that begins in the nucleus and concludes in the cytoplasm. It starts with the transcription of miRNA genes by RNA polymerase II into primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs), which are then processed by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex into precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs). These pre-miRNAs are exported to the cytoplasm, where they undergo further processing by the Dicer enzyme to generate mature miRNA duplexes. One strand of the duplex, the mature miRNA, is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), while the other strand is typically degraded. MiRNAs mediate gene silencing through their incorporation into the RISC, directing the complex to target mRNAs via complementary base pairing. This interaction primarily occurs at the 3' untranslated region (3' UTR) of target mRNAs, leading to one of two outcomes: mRNA degradation or translational repression. The choice between these outcomes depends on the degree of complementarity between the miRNA and its target mRNA. Perfect or near-perfect complementarity usually results in mRNA cleavage and degradation, whereas partial complementarity leads to translational repression. Through these mechanisms, a single miRNA can regulate the expression of multiple genes, and conversely, a single gene can be targeted by multiple miRNAs, creating a complex regulatory network.

Biological Roles of miRNAs

The biological roles of miRNAs are diverse and impact almost every cellular process, including development, differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and metabolism. Their ability to finely tune gene expression enables cells to respond dynamically to environmental changes and maintain homeostasis. In development, miRNAs are critical for proper timing and patterning of gene expression, influencing cell fate decisions and morphogenesis. In the immune system, miRNAs modulate the development and response of immune cells, playing roles in both innate and adaptive immunity. MiRNAs also have significant implications in disease, particularly in cancer, where they can act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors. Dysregulation of miRNA expression can lead to aberrant cell growth, invasion, and metastasis. In cardiovascular diseases, miRNAs are involved in processes such as cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and angiogenesis. Furthermore, their role in metabolic disorders, neurological conditions, and infectious diseases highlights the potential for miRNA-based diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets.

MicroRNA Dynamics and Pathogenesis in Brain Tumors

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are integral components of the cellular machinery, governing the fine-tuning of gene expression across a multitude of biological processes. These small, non-coding RNA molecules, approximately 22 nucleotides in length, serve as key regulatory elements by binding to complementary sequences on target messenger RNAs (mRNAs), typically resulting in gene silencing through translational repression or mRNA degradation. The universality and precision of miRNA-mediated regulation underscore its significance in maintaining cellular homeostasis and orchestrating complex biological functions such as development, differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and the stress response. During embryonic development and tissue differentiation, precise spatial and temporal control of gene expression is essential. miRNAs play a critical role in this regulatory landscape by ensuring the appropriate expression levels of developmental genes and signaling molecules. For instance, the let-7 family of miRNAs is highly conserved across species and has been implicated in the regulation of cell differentiation and maturation. By targeting multiple genes involved in cell cycle progression and differentiation pathways, miRNAs like let-7 contribute to the fine-tuning of developmental processes and prevent premature or inappropriate cell differentiation. Cellular proliferation and apoptosis are tightly regulated to maintain tissue homeostasis, with miRNAs acting as crucial modulators of these processes. For example, miR-21, often upregulated in various cancers, promotes cell proliferation and survival by targeting tumor suppressor genes and pro-apoptotic factors, thereby contributing to oncogenesis. Conversely, the miR-34 family is directly activated by the tumor suppressor p53 and induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in response to DNA damage and oncogenic stress, serving as an anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic influence. Cells exposed to environmental stressors, including oxidative stress, hypoxia, and nutrient deprivation, undergo adaptive responses to restore homeostasis, with miRNAs playing pivotal roles. For instance, miRNAs modulate the cellular response to hypoxia by regulating the expression of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) and other genes involved in angiogenesis, metabolism, and cell survival. This adaptive mechanism highlights the importance of miRNAs in enabling cells to cope with fluctuating environmental conditions and stresses. In the context of cancer, the dichotomous nature of miRNAs as both oncogenes (oncomiRs) and tumor suppressors is particularly evident. OncomiRs, such as miR-155 and miR-21, are frequently overexpressed in tumors and promote oncogenesis by silencing tumor suppressor genes, enhancing cell proliferation, and inhibiting apoptosis. In contrast, tumor-suppressive miRNAs, including the let-7 and miR-34 families, are often downregulated in cancers, leading to the upregulation of oncogenes and promotion of tumor progression. The role of miRNAs in brain tumors like glioblastoma, meningioma, and medulloblastoma illustrates the complexity of miRNA-mediated regulation in oncogenesis. For example, in glioblastoma, the downregulation of tumor suppressor miRNAs and upregulation of oncomiRs contribute to the aggressive nature of the tumor, affecting cell cycle control, apoptosis, invasion, and angiogenesis.

Glioblastoma

Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) stands as the most common and aggressive form of primary brain tumor, posing significant challenges in the realms of neuro-oncology and patient care. It accounts for approximately 50% of all malignant brain tumors, a statistic that underscores its prevalence and the urgency of advancing our understanding and treatment methodologies. This paper aims to provide an in-depth examination of GBM, covering its pathology, clinical manifestations, diagnostic challenges, and the latest advancements in treatment modalities. The pathological underpinnings of GBM are complex and multifaceted. GBM tumors are characterized by high cellular heterogeneity, rapid growth, and a propensity for extensive brain invasion. We explore the histopathological features of GBM, such as necrosis and vascular proliferation, and how these contribute to its aggressive behavior. Clinically, GBM presents with a range of symptoms that are largely dependent on the tumor’s location in the brain. These symptoms can include headaches, seizures, cognitive and motor deficits, and personality changes. Diagnosing GBM accurately is critical for effective treatment planning. The examination of the role of advanced neuroimaging techniques, primarily MRI, in identifying the characteristic features of GBM, such as ring-enhancing lesions, serves as a vital advancement in diagnosing tumors. Additionally, the role of biopsy and histological examination in confirming the diagnosis and the emerging role of molecular diagnostics in understanding the tumor’s specific genetic makeup can guide targeted therapy. The treatment landscape for GBM has evolved significantly but remains a challenging endeavor. Surgical resection, while often not curative, plays a critical role in reducing tumor burden and improving symptoms. The advancements in neurosurgical techniques has. maximized tumor removal while minimizing damage to normal brain tissue. Radiation therapy and chemotherapy, particularly temozolomide, have been standard treatments, but their efficacy is often limited by tumor resistance and recurrence.

MicroRNA Regulatory Dynamics in GBM

The intricate network of miRNA regulation in GBM plays a critical role in its pathogenesis, influencing key cellular processes such as cell cycle control, apoptosis, invasion, and angiogenesis. These small non-coding RNA molecules can act either as oncogenes (oncomiRs) or tumor suppressors, depending on their target genes within the tumor.

- • miR-21: Perhaps the most well-characterized oncomiR in GBM, miR-21 promotes tumor growth by targeting and downregulating various tumor suppressor genes, including PTEN, PDCD4, and TPM1. This results in the activation of survival pathways such as PI3K/AKT and attenuation of apoptosis, contributing to the aggressive nature of Therapeutic strategies aiming to inhibit miR-21 have shown promise in preclinical models, offering a potential avenue for GBM treatment.

- • miR-34a: This miRNA functions as a potent tumor suppressor in GBM by directly targeting genes involved in cell cycle progression and survival, such as CDK6, CDK4, and The downregulation of miR-34a in GBM contributes to unchecked cell division and resistance to cell death. Strategies to restore or mimic miR-34a function are under investigation as potential therapeutic approaches.

- • miR-10b and miR-221/222: These miRNAs are involved in the regulation of GBM cell invasion and angiogenesis. miR-10b enhances tumor invasion by targeting HOXD10, thereby upregulating pro-invasive genes. miR-221/222 contribute to angiogenesis and resistance to apoptosis by targeting TIMP3 and p27^Kip1, Inhibiting these miRNAs could reduce GBM invasiveness and improve therapy responsiveness.

- • Let-7: The Let-7 family of miRNAs, known for its role in regulating cell differentiation and proliferation, is frequently downregulated in Let-7 targets components of the RAS/MAPK pathway, and its restoration in GBM models has shown to reduce cell proliferation and increase sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents.

Meningioma

Meningiomas are the most common type of primary brain tumors, accounting for about one-third of all cases. Originating from the meninges, the protective membranes that envelop the brain and spinal cord, these tumors are more prevalent in adults, especially in individuals between the ages of 40 and 70, and tend to have a higher incidence in women compared to men. The majority of meningiomas are benign (WHO Grade I), growing slowly and often asymptomatic for years. However, a small percentage are atypical (WHO Grade II) or malignant (WHO Grade III), exhibiting more aggressive behavior and a higher likelihood of recurrence after treatment.

The diagnosis of meningiomas typically involves imaging techniques such as MRI and CT scans, which can effectively detect the tumor's presence and determine its size and impact on surrounding tissues. Symptoms, when they occur, depend on the tumor's location and may include headaches, seizures, visual disturbances, and changes in neurological function, such as weakness or numbness in parts of the body. Prognosis for meningioma patients varies widely based on the tumor's grade, size, and location, as well as the patient's overall health. While surgical removal is the preferred treatment for accessible meningiomas, the complete resection may be challenging if the tumor is located near critical brain structures. Radiation therapy is another treatment option, particularly for small, residual, or inoperable tumors. The prognosis for patients with benign meningiomas is generally favorable, with many achieving long-term survival following treatment. However, atypical and malignant meningiomas carry a higher risk of recurrence and may require a more aggressive treatment approach, including adjuvant radiation or chemotherapy. Recent advancements in molecular biology have begun to shed light on the genetic and environmental factors contributing to the development of meningiomas. Understanding these factors could lead to the identification of new therapeutic targets and the development of more effective, personalized treatment strategies. Despite their generally benign nature, meningiomas can significantly impact patients' quality of life, underscoring the importance of ongoing research and innovation in their diagnosis and management.

miRNAs as Tumor Suppressors in Meningiomas

Several miRNAs have been identified as tumor suppressors in meningiomas, where their downregulation contributes to tumorigenesis and progression:

- • miR-200 Family: This group of miRNAs is crucial in regulating epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process not only important in metastasis but also in local invasion, which is particularly relevant for meningiomas given their potential to invade local Downregulation of the miR-200 family leads to enhanced expression of EMT markers, promoting a more aggressive phenotype.

- • miR-145: Demonstrates tumor-suppressive activity by targeting multiple pathways involved in cell cycle control and In meningiomas, miR-145 downregulation has been associated with increased cell growth and reduced apoptosis, indicating its potential role in tumor progression.

- • miR-218: Identified as a suppressor of meningioma cell migration and invasion by targeting the Robo1 receptor, a known mediator of cellular Lower expression levels of miR-218 correlate with higher tumor grade and increased invasive capacity.

miRNAs as Oncogenes in Meningiomas

Conversely, certain miRNAs function as oncogenes in meningiomas, promoting tumor growth and survival:

- • miR-21: Similar to its role in glioblastomas, miR-21 acts as an oncomiR in meningiomas, targeting and downregulating various tumor suppressor genes, including PTEN and Its overexpression is associated with tumor growth, survival, and resistance to apoptosis.

- • miR-10b: Enhances cell proliferation and prevents apoptosis by downregulating the pro-apoptotic protein Bim. Elevated levels of miR-10b have been linked to higher tumor grades and poorer outcomes.

Regulatory Networks and Pathway Interactions

miRNAs in meningiomas do not act in isolation but are part of intricate regulatory networks that affect key signaling pathways:

- • Hedgehog Signaling Pathway: miRNAs such as miR-125b are involved in the regulation of the Hedgehog signaling pathway, which plays a role in cell differentiation and Dysregulation of this pathway has been implicated in the pathogenesis of various tumors, including meningiomas.

- • Wnt/β-catenin Pathway: Several miRNAs, including members of the miR-200 family, regulate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which is critical for tissue development and Aberrant activation of this pathway has been observed in meningiomas, contributing to tumorigenesis.

Medulloblastoma

Medulloblastoma is the most common malignant pediatric brain tumor, predominantly affecting children and accounting for approximately 20% of all pediatric brain tumors. It originates in the cerebellum or posterior fossa region of the brain and is known for its aggressive nature and potential to metastasize to other parts of the CNS via cerebrospinal fluid. Medulloblastoma's clinical management challenges stem from its rapid growth, invasive nature, and the young age of the patients it typically affects. The understanding of medulloblastoma has evolved significantly with the identification of four major molecular subgroups, which have distinct genetic profiles, clinical presentations, and responses to therapy.

- • WNT: characterized by activation of the Wnt signaling pathway, this subgroup has the best prognosis among all medulloblastoma subtypes, with a survival rate exceeding 90%. Patients typically have mutations in the CTNNB1 gene (encoding β-catenin)

- • SHH: Named after the Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway, which is abnormally activated in these tumors due to mutations in PTCH1, SMO, or SUFU This subgroup presents a variable prognosis dependent on age, with infants and adults faring better than children.

- • Group 3: This subgroup is associated with the worst prognosis, partly due to a high incidence of metastatic disease at diagnosis and a high frequency of MYC Patients often present with large, rapidly growing tumors.

- • Group 4: Although the genetic drivers of Group 4 are less well understood, it is the most common These tumors often have amplifications of genes like MYCN and isochromosome 17q. The prognosis for Group 4 patients is intermediate between WNT and Group 3.

The pathogenesis of medulloblastoma involves a complex interplay of genetic mutations and dysregulated signaling pathways leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation, resistance to apoptosis, and potential for metastasis. Abnormalities in developmental pathways, including WNT and SHH, play a crucial role in tumor initiation and progression. Symptoms of medulloblastoma typically arise from increased intracranial pressure due to tumor growth and obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid flow. Common symptoms include headache, nausea, vomiting, lethargy, and ataxia. Due to its location in the cerebellum, patients may also experience problems with balance and coordination. Diagnosis of medulloblastoma involves neuroimaging, with MRI being the gold standard, followed by histopathological examination of tumor tissue obtained via surgery. Treatment usually consists of a multimodal approach including surgical resection, aimed at removing as much of the tumor as possible, followed by radiation therapy and chemotherapy. The intensity of treatment is often adjusted based on the patient's age, tumor subgroup, and presence of metastatic disease, to balance efficacy with long-term side effects. While the overall prognosis for medulloblastoma has improved significantly, with long-term survival rates now around 70-80%, outcomes vary widely by molecular subgroup and stage of disease. Long-term survivors often face treatment-related side effects, including neurocognitive deficits, highlighting the need for therapies that are both effective and less toxic. Current research focuses on better understanding the molecular underpinnings of medulloblastoma to develop targeted therapies, improve risk stratification, and reduce therapy-related morbidity.

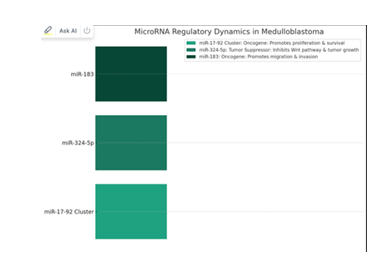

MicroRNA Regulatory Dynamics in Medulloblastoma

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) play a critical role inthe pathogenesis of medulloblastoma, with various miRNAs acting as oncogenes or tumor suppressors. These small, non-coding RNA molecules regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally and are involved in numerous cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and migration.

- • miR-17-92 Cluster: Known as anoncogenic miRNA cluster, miR-17-92 is overexpressed in certain medulloblastoma subgroups, particularly those classified under the Group 3 and Group 4 It promotes cell proliferation and survival by targeting multiple genes involved in the cell cycle and apoptosis pathways, such as PTEN and BIM. The oncogenic role of the miR-17-92 cluster highlights its potential as a therapeutic target, where inhibiting this cluster could lead to reduced tumor growth and improved patient outcomes.

- • miR-324-5p: This miRNA targets the Wnt signaling pathway, which is crucial for the development and progression of WNT-subgroup medulloblastomas. By inhibiting components of the Wnt pathway, miR-324-5p acts as a tumor suppressor, and its upregulation has been shown to inhibit tumor Therapeutic strategies that mimic or enhance miR-324-5p expression could offer a promising approach for treating

WNT-subgroup medulloblastomas.

- • miR-183: Functions as an oncomiR in medulloblastoma by promoting cell migration and invasion, mechanisms essential for tumor metastasis. miR-183 targets genes involved in cell adhesion and motility, facilitating the metastatic spread of tumor Inhibiting miR-183 could potentially reduce the metastatic potential of medulloblastoma cells, offering a strategy to limit tumor dissemination and improve patient prognosis.

Comparative Analysis Across Brain Tumors

In Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM), miRNAs play a pivotal role in modulating key cellular processes such as cell cycle control, apoptosis, invasion, and angiogenesis. Notably, miR-21 acts as a prominent oncomiR by targeting and downregulating tumor suppressor genes, promoting tumor growth and resistance to apoptosis. Conversely, miR-34a functions as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting cell cycle progression and survival pathways. Other miRNAs, such as miR-10b and miR-221/222, regulate invasion and angiogenesis, suggesting their potential as therapeutic targets to mitigate tumor aggressiveness. In Meningioma, miRNAs exhibit dichotomous roles as both tumor suppressors and oncogenes. Downregulation of miRNAs such as the miR-200 family and miR-145 contributes to tumor progression by promoting cell proliferation and invasion. Conversely, miR-218 acts as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting cell migration and invasion. On the other hand, miRNAs like miR-21 andmiR-10b function as oncogenes, enhancing tumor growth and survival. These findings underscore the complexity of miRNA regulation in meningiomas and highlight potential therapeutic targets for intervention. In Medulloblastoma, miRNAs exert significant influence on tumor pathogenesis and progression. Oncogenic miRNAs such as the miR-17-92 cluster promote cell proliferation and survival by targeting key tumor suppressor genes. Conversely, tumor suppressor miRNAs like miR-324-5p inhibit tumor growth by targeting crucial signaling pathways such as Wnt. Additionally, miR-183 functions as an oncomiR, facilitating tumor metastasis through the regulation of cell migration and invasion. These insights into the role of miRNAs in medulloblastoma offer opportunities for targeted therapies aimed at modulating miRNA expression and activity. While certain miRNAs exhibit consistent roles as oncogenes or tumor suppressors across these tumors, others demonstrate context-dependent functions. Understanding the intricate interplay between miRNAs and their target genes in each tumor type is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies tailored to individual patient profiles.

Comparative analysis of MiR-21's Oncogenic Role

In GBM, miR-21 emerges as a pivotal oncomiR orchestrating a complex network of oncogenic signaling pathways. By targeting critical tumor suppressor genes such as PTEN, PDCD4, and TPM1, miR-21 promotes tumor growth, invasion, and therapy resistance. Its activation of pro-survival pathways, including PI3K/AKT, fuels GBM aggressiveness, underscoring its significance as a therapeutic target. Similarly, in meningioma, miR-21 exerts oncogenic effects by targeting tumor suppressor genes and promoting tumor growth and invasion. Its involvement in modulating the tumor microenvironment further contributes to meningioma progression, highlighting its role in fostering a conducive milieu for tumor growth and metastasis. In contrast, the role of miR-21 in medulloblastoma unveils nuanced dynamics, reflecting the tumor's molecular heterogeneity. While miR-21 exhibits oncogenic properties in certain subgroups, such as those characterized by the miR-17-92 cluster, its impact varies across molecular subtypes. The differential regulation of miR-21 in medulloblastoma underscores the importance of considering tumor heterogeneity in therapeutic interventions targeting miRNAs.

MicroRNA Impacts on Autism Synaptic Development and Brain Function

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs that play crucial roles in regulating gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. They are involved in various biological processes, including development, differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis. In the context of neurological disorders, especially autism spectrum disorder (ASD), miRNAs have drawn significant attention due to their impact on brain development and synaptic function. Understanding the identification and function of miRNAs implicated in autism provides insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying the disorder and may offer new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Identification of miRNAs Implicated in Autism

Research has identified several miRNAs whose expression levels are altered in individuals with autism, suggesting a potential role in the disorder's etiology. Techniques such as next-generation sequencing (NGS), microarrays, and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) have been instrumental in identifying these miRNAs. Studies comparing brain tissues or peripheral samples (like blood) from autistic individuals and control groups have highlighted specific miRNAs that are either upregulated or downregulated in autism.For example, miR-132 and miR-181b have been reported to have altered expression in autism. These miRNAs are known to regulate neuronal development and synaptic plasticity, processes that are crucial for normal brain function and are often disrupted in ASD.

Functions of miRNAs in Brain Development and Synaptic Function

- • Regulation of Neuronal Development: miRNAs are involved in various stages of neuronal development, including neural stem cell proliferation, differentiation, and By regulating the expression of genes involved in these processes, miRNAs can influence the overall structure and function of the brain.

- • Synaptic Plasticity: miRNAs also play a critical role in synaptic plasticity, the ability of synapses to strengthen or weaken over This is crucial for learning and memory. miRNAs can modulate the expression of proteins involved in synaptic transmission and plasticity, thereby affecting neural circuitry and behavior.

- • Neurotransmission: Certain miRNAs are known to target the mRNAs of neurotransmitter receptors, transporters, and enzymes, thereby regulating neurotransmitter levels and signaling Alterations in these miRNAs can lead to imbalances in neurotransmitter systems associated with ASD, such as glutamatergic, GABAergic, and serotonergic systems.

Implications for Autism Spectrum Disorder

The dysregulation of miRNAs in autism suggests that they could be contributing to the developmental and functional abnormalities observed in the disorder. By affecting gene expression patterns critical for brain development and function, miRNAs could influence the trajectory of neural development, leading to the symptoms observed in ASD. Furthermore, the identification of autism-associated miRNAs offers potential biomarkers for early diagnosis and targets for therapeutic intervention. For example, molecules that mimic or inhibit specific miRNAs (miRNA mimics or antagomirs) could be developed to restore normal gene expression patterns.

The Role of Genetic Mutations in Neurological Disease Pathogenesis

Genetic mutations play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of numerous neurological diseases, ranging from neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease to neurodevelopmental disorders and brain tumors. These mutations can be inherited or occur spontaneously, altering the normal functioning of the nervous system in profound ways. At the molecular level, genetic mutations can lead to the production of abnormal proteins, interfere with gene expression, or disrupt cellular processes. In neurodegenerative diseases, for example, specific mutations are known to result in the accumulation of toxic proteins within neurons, leading to cell death and the progressive loss of neurological function. These diseases often have a genetic component, with mutations in certain genes increasing the risk of developing the condition. Interestingly, the realm of neurological diseases intersects with oncogenesis, the process by which normal cells are transformed into cancer cells. While the primary concern in neurodegenerative diseases and neurodevelopmental disorders is the loss of normal neuronal function, in the context of brain tumors, genetic mutations can lead to unchecked cell growth and malignancy. This demonstrates the diverse outcomes that can arise from genetic alterations in the nervous system. Genetic alterations contribute to the pathophysiology of brain tumors and neurodevelopmental disorders in several key ways. In the case of brain tumors, mutations in genes that regulate cell cycle progression, apoptosis (programmed cell death), and DNA repair can result in the formation and growth of tumors. For example, mutations in the TP53 gene, a critical tumor suppressor, are commonly found in various types of brain tumors. These genetic changes can disrupt the delicate balance between cell proliferation and death, leading to tumor development. In neurodevelopmental disorders, mutations may affect genes involved in brain development, synaptic function, and neuronal connectivity. Conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have been linked to mutations in genes that influence neuronal communication and plasticity. These genetic alterations can lead to abnormal brain development and function, manifesting as the cognitive, behavioral, and social challenges characteristic of these disorders.

Genetic Mutations and Their Mechanisms in Neurodegeneration

- Protein Misfolding and Aggregation: Many neurodegenerative diseases are associated with the accumulation of misfolded proteins, which can form insoluble aggregates in the For example, mutations in the gene encoding for the amyloid precursor protein (APP) or presenilin genes (PSEN1, PSEN2) in Alzheimer’s disease lead to the abnormal production and accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques. Similarly, mutations in the alpha-synuclein gene (SNCA) are linked to the formation of Lewy bodies in Parkinson's disease. These aggregates interfere with neuronal function and initiate a cascade of neurodegenerative processes.

- Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Mitochondria are crucial for energy production in cells, and their dysfunction is a hallmark of several neurodegenerative Genetic mutations can impair mitochondrial function, leading to reduced energy production and increased oxidative stress. For instance, mutations in the superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) gene in ALS and the Parkin gene (PRKN) in Parkinson’s disease can cause mitochondrial dysfunction, contributing to neuronal degeneration.

- Neuroinflammation: Genetic mutations can also influence the immune response in the brain, leading to chronic neuroinflammation, which exacerbates neurodegeneration. Mutations in genes like TREM2, which plays a role in the immune response in the brain, have been linked to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. This chronic inflammation can further damage neuronal cells and contribute to the progression of neurodegenerative

- Impaired Autophagy and Protein Clearance: Autophagy is a cellular process that degrades and recycles damaged cellular components, including Mutations that impair autophagy can lead to the accumulation of damaged proteins and organelles, contributing to neurodegeneration. For example, mutations in genes involved in the autophagy-lysosome pathway, such as LRRK2 in Parkinson’s disease, can impair the clearance of alpha-synuclein, leading to its accumulation.

- Axonal Transport Defects: Neurons rely on axonal transport to move materials between the soma and synaptic Mutations in genes that regulate this process can lead to the accumulation of proteins and organelles in axons, disrupting neuronal function and contributing to disease. Mutations in the tau gene (MAPT), which is involved in microtubule stabilization and axonal transport, are linked to frontotemporal dementia and other tauopathies.

Genetic Overview of Brain Tumors

Glioblastoma: Genetic Mutations and Pathophysiology

Glioblastoma, the most aggressive and common form of malignant brain tumor in adults, presents a complex genetic landscape characterized by a variety of mutations that drive its pathophysiology.

Key mutations include:

- • IDH1/IDH2 Mutations: Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) mutations are early events in gliomagenesis, linked to a subset of glioblastomas with better prognosis. These mutations result in the accumulation of 2-hydroxyglutarate, an oncometabolite that contributes to

- • TP53 Mutations: Alterations in TP53, a tumor suppressor gene, are common in glioblastoma and contribute to cell cycle deregulation and genomic

- • EGFR Amplification: Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) amplification occurs in approximately 50% of glioblastomas, leading to enhanced proliferative signaling.

- • TERT Promoter Mutations: Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutations, which activate telomerase expression, are associated with increased tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis.

Meningioma: Genetic Landscape and Clinical Implications

Meningiomas arise from the meninges and show a diverse genetic landscape with implications for their biology and clinical management. Notable genetic alterations include:

- • NF2 Mutations: Neurofibromin 2 (NF2) gene mutations are the most common genetic event in meningiomas, leading to loss of merlin protein function, which normally inhibits cell

- • AKT1 and SMO Mutations: Mutations in AKT1 and Smoothened (SMO) are associated with specific meningioma subtypes and may offer targets for

- • TERT Promoter Mutations: Similar to glioblastomas, TERT promoter mutations in meningiomas are linked to higher tumor grade and worse

Medulloblastoma: Genetic Heterogeneity and Disease Mechanics

Medulloblastoma is the most common malignant pediatric brain tumor, exhibiting significant genetic heterogeneity that influences its pathology and treatment response. Key genetic subgroups include:

- • WNT Pathway Activation: Mutations leading to activation of the WNT signaling pathway, particularly in the CTNNB1 gene, are associated with a favorable

- • SHH Pathway Activation: Mutations affecting the Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) pathway, such as in PTCH1, SMO, and SUFU, define a subgroup with distinct biology and variable

- • Group 3 and Group 4: These subgroups are less well characterized but are known to involve MYC amplification in Group 3, leading to a particularly aggressive tumor phenotype, and various chromosomal copy number alterations in Group

Genetic Landscape of Brain Tumors

The common genetic mutations across glioblastoma, meningioma, and medulloblastoma reveal a complex interplay of oncogenic and tumor suppressor gene alterations that drive tumor development, progression, and response to therapy. While each tumor type exhibits unique genetic features, they share mechanisms such as cell cycle deregulation, signaling pathway activation, and telomerase activation that underlie tumorigenesis.

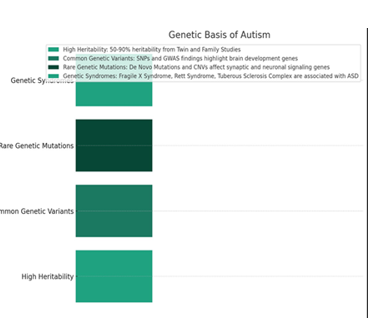

Genetic Basis of Autism

High Heritability and Genetic Contribution

- • Twin and Family Studies: Consistently demonstrate that autism has a higher concordance rate among monozygotic twins compared to dizygotic twins, supporting a significant genetic basis. These studies estimate the heritability of ASD to be approximately 50-90%, although this range varies depending on the study and the population examined.

Common Genetic Variants

- • SNPs and GWAS Findings: Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) identified through Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) have pinpointed several loci associated with a slight increase in ASD risk. Notable among these are variants near genes involved in brain development and synaptic function, such as those affecting neuronal cell adhesion and the organization of the cortical layers.

Rare Genetic Mutations

- • De Novo Mutations: These mutations, which occur spontaneously rather than being inherited, are particularly insightful. Genes affected by de novo mutations in ASD include those coding for synaptic proteins, transcriptional regulators, and chromatin-remodeling proteins. For instance, mutations in CHD8, associated with chromatin remodeling, have been linked to a subset of ASD cases characterized by macrocephaly, gastrointestinal issues, and distinct facial features.

- • Copy Number Variations (CNVs): CNVs involve duplications or deletions of large DNA segments. ASD-associated CNVs often encompass genes critical for synaptic formation and neuronal signaling. The 16p11.2 deletion and duplication syndromes are examples, with affected individuals showing a range of neurodevelopmental disorders, including ASD.

Genetic Syndromes Associated with ASD

- • Fragile X Syndrome (FXS): The most common single-gene cause of ASD and the leading cause of inherited intellectual disability. FXS is caused by a CGG triplet repeat expansion in the FMR1 gene, leading to reduced levels or absence of the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), essential for normal neural development.

- • Rett Syndrome: Primarily affects females and is caused by mutations in the MECP2 gene. Although individuals with Rett Syndrome may show ASD-like symptoms early in life, the progression and clinical features diverge significantly from classic ASD.

- • Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC): Caused by mutations in either TSC1 or TSC2, leading to the growth of non-malignant tumors in the brain and other vital organs. A significant proportion of individuals with TSC exhibit ASD symptoms, highlighting a link between neural growth pathways and ASD phenotypes.

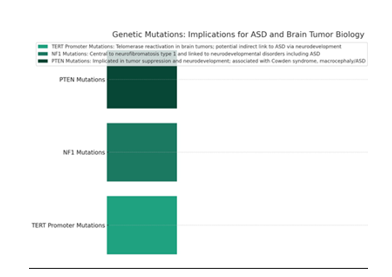

Comparative Genetic Analysis: Brain Tumors and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

The genetic underpinnings of brain tumors and neurodevelopmental disorders such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) offer a unique lens through which we can understand the complex interplay between gene mutations, cellular pathways, and disease phenotypes. Both categories of disorders are characterized by diverse genetic alterations, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), copy number variations (CNVs), and specific gene mutations. A comparative analysis, particularly with an emphasis on microRNAs (miRNAs), can shed light on shared biological mechanisms and identify potential therapeutic targets.

Key Mutations and Their Roles

- • TERT Promoter Mutations: In brain tumors, particularly glioblastomas and meningiomas, TERT promoter mutations are prevalent, leading to telomerase reactivation and cellular immortality. Although not directly implicated in ASD, the role of telomere length and maintenance in neurodevelopmental processes and neuronal stem cell proliferation suggests an indirect link worth exploring.

- • Neurofibromin 1 (NF1) Mutations: NF1 mutations are central to the development of neurofibromatosis type 1, which can lead to brain tumors. Interestingly, NF1 mutations have also been linked to neurodevelopmental disorders, including learning disabilities and ASD, indicating a shared pathway influencing neurodevelopment and tumor suppression.

- • PTEN Mutations: PTEN is another gene implicated in both tumor suppression and neurodevelopment. Mutations in PTEN can lead to conditions like Cowden syndrome, associated with an increased risk of brain tumors, and macrocephaly/ASD. This suggests a critical role of PTEN in regulating cell growth and neurodevelopment.

Research on Specific Mutations and Their Roles

- • Shared Genetic Pathways: Both brain tumors and ASD demonstrate alterations in pathways that are crucial for cell cycle regulation, differentiation, and synaptic function. For instance, the TERT promoter mutations prevalent in glioblastoma and meningioma, which activate telomerase and contribute to cellular immortality, might not have direct analogs in ASD. However, the focus on cellular growth pathways uncovers a potential bridge via miRNA regulation.

- • MicroRNAs in Regulation: miRNAs have been implicated in a wide array of biological processes, including those aberrant in both brain tumors and ASD. In brain tumors, specific miRNAs can act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors. Similarly, in ASD, deregulated miRNAs might affect neurodevelopment and synaptic plasticity. For example, miR-137, which is implicated in neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity, has been found to be dysregulated in both glioblastoma and ASD, suggesting a potential common mechanism through which cellular proliferation and synaptic development are modulated.

Neurodevelopmental Genes and Cancer

Genes involved in neurodevelopment, such as those affecting synaptic formation (e.g., SHANK3, NLGN3/4) and neuronal signaling in ASD, have parallels in brain tumor biology. Mutations or dysregulations in these genes can disrupt normal cell signaling pathways, leading to overgrowth in the case of tumors, or impaired connectivity in the case of ASD.

Gene Editing in Brain Tumors

Advanced Genetic Surgeries and Procedures in Brain Tumor Management

In the dynamic field of neuro-oncology, the introduction of genetic engineering technologies, particularly CRISPR-Cas9, has marked the beginning of a transformative era in precision medicine, significantly influencing the management and treatment of brain tumors. This evolution in care is characterized by the development and application of advanced genetic surgeries and procedures, which leverage the profound insights offered by genetic research to enhance treatment efficacy and patient safety. Advanced targeted surgical interventions have emerged as a cornerstone in this new era, integrating genetic insights into neurosurgical practices to achieve precision in tumor resection while safeguarding the surrounding healthy brain tissue. Among these innovations, fluorescence-guided surgery stands out. This technique utilizes genetic markers to fluorescently label tumor cells, markedly enhancing their visibility during surgical procedures. This innovation has significantly improved the precision of tumor resections, effectively reducing the risk of post-operative neurological deficits and optimizing patient recovery outcomes. The rapid evolution of targeted interventions has been supported by breakthroughs in intraoperative imaging and molecular diagnostics, enabling surgeons to differentiate between malignant and healthy brain tissue in real-time with unprecedented accuracy. Concurrently, the CRISPR-Cas9 system, a pioneering gene-editing tool, is under extensive investigation in clinical trials for its ability to directly modify genes associated with brain tumors. These early-phase trials aim to assess the feasibility of using CRISPR-Cas9 to target specific mutations in glioblastoma cells, with objectives ranging from increasing the cells' susceptibility to conventional treatments to enhancing the patient's immune response against the tumor. Despite the promise shown by CRISPR-Cas9, these trials face challenges such as developing efficient delivery mechanisms that target tumor cells with precision, minimizing off-target effects to ensure safety, and guaranteeing the durability of therapeutic outcomes. In parallel, gene therapy has been identified as a frontier in the treatment of brain tumors, offering a novel avenue to correct or counteract the genetic mutations that drive tumor growth.

This approach involves using viral vectors to deliver therapeutic genes directly into tumor cells, aiming to restore normal cell function or induce cell death. The strategies include introducing tumor suppressor genes, suicide genes that make tumor cells more sensitive to pharmacological agents, or genes that boost the immune system's ability to combat tumor cells. The specificity of gene therapy, combined with advancements in vector technology, presents a promising treatment modality that could potentially overcome the limitations of traditional therapies. The integration of these genetic surgeries and gene therapy techniques into neuro-oncology signifies a significant shift towards personalized medicine, tailoring therapeutic interventions to the unique genetic profile of each tumor. This approach enhances the efficacy of treatments while minimizing adverse effects. Personalized medicine in neuro-oncology also encompasses personalized monitoring strategies, enabling the early detection of tumor recurrence and the adjustment of treatment plans based on the genetic evolution of the tumor. Comprehensive genomic profiling's successful integration into clinical practice is crucial for realizing the full potential of personalized medicine, necessitating ongoing research and multidisciplinary collaboration.

In conclusion, the landscape of brain tumor management is being reshaped by advances in genetic engineering and personalized medicine, offering the prospect of significantly improved outcomes for patients. As these technologies continue to evolve, the potential for dramatically transforming patient care in neuro-oncology becomes increasingly tangible. However, challenges remain, including optimizing delivery methods and ensuring specificity and safety, which are the focus of current research efforts. These endeavors are paving the way for a new generation of brain tumor therapies, marking a significant leap forward in our ability to treat and manage these complex conditions.

Gene Editing in Autism

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by a wide range of symptoms and severities, influenced significantly by complex genetic factors. The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has heralded a new era in autism research, offering unprecedented precision and versatility in understanding and potentially treating this condition.CRISPR-Cas9 stands out for its ability to target and edit specific genetic sequences with high accuracy, which is vital in a disorder as genetically complex as ASD. This technology enables researchers to dissect the contributions of individual genes to ASD, shedding light on the disorder's underlying biological mechanisms. Its versatility allows for its application across various research contexts, from identifying autism-related genes to creating model organisms and cell lines that mimic the genetic conditions of ASD, facilitating a deeper understanding of the disorder's pathology.The use of CRISPR-Cas9 has significantly accelerated the identification of genes associated with ASD. By selectively editing genes suspected to contribute to ASD, researchers can observe the resultant effects on cellular and developmental processes, directly linking specific genetic alterations to ASD phenotypes.

This precise manipulation not only confirms the involvement of certain genes in ASD but also uncovers how alterations in these genes disrupt normal neural development and function.Perhaps the most promising aspect of CRISPR-Cas9 technology is its potential to pave the way for novel therapeutic interventions. By correcting genetic mutations at their source, there is the possibility of developing treatments that address the root causes of ASD rather than merely alleviating symptoms. This approach opens up the potential for gene therapy in ASD, where specific genetic mutations could be corrected in individuals with the disorder, offering a tailored and potentially curative treatment.While the potential of CRISPR-Cas9 in ASD research and treatment is immense, several challenges remain. Ethical considerations, off-target effects, and the delivery of CRISPR components to the human brain are among the hurdles that need to be addressed. Moreover, the genetic heterogeneity of ASD means that therapies may need to be highly individualized, presenting additional challenges in terms of treatment design and implementation. Despite these challenges, the ongoing advancements in CRISPR technology and its application in ASD research continue to offer hope for a future where genetic editing could play a critical role in understanding and treating Autism Spectrum Disorder.

As research progresses, the potential for CRISPR-Cas9 to not only illuminate the genetic foundations of ASD but also to offer concrete avenues for intervention becomes increasingly apparent, marking a significant leap forward in the quest to improve the lives of those affected by ASD.

Key Studies and Findings

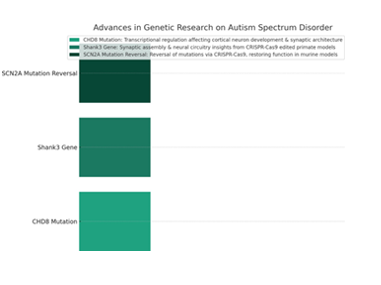

CHD8 Mutation and Autism

Investigations into the CHD8 gene, implicated in neurodevelopmental processes, have delineated a robust association between its mutagenic disruptions and the manifestation of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). CHD8, serving as a transcriptional regulator, plays a pivotal role in the orchestration of gene expression networks essential for cortical neuron development and synaptic architecture. Mutations within this gene are correlated with aberrations in neuronal proliferation, differentiation, and synaptogenesis, mechanisms fundamental to cerebral cortex formation and function. Specifically, research has elucidated that CHD8 mutations induce alterations in the expression of genes critical for neural development, leading to dysregulated neuronal morphology and impaired synaptic connectivity. These molecular and cellular defects contribute to the neuropathological underpinnings of ASD, offering insights into the genotype-phenotype correlations that characterize this disorder. The elucidation of CHD8’s role underscores the potential for targeted genetic interventions aimed at rectifying these developmental disruptions.

Shank3 Gene and Autism Models

The Shank3 gene, integral to synaptic assembly and neural circuitry, has emerged as a focal point in autism research, particularly through the application of CRISPR-Cas9 mediated gene editing in primate models. By engineering precise mutations in the Shank3 gene within these models, researchers have replicated critical aspects of the ASD phenotype, including deficits in social interaction and repetitive behavior patterns, alongside neurobiological abnormalities akin to those observed in human conditions. These primate studies have facilitated a nuanced understanding of Shank3’s role in synaptic function and plasticity, revealing specific disruptions in synaptic density and neurotransmission. The phenotypic and neurobiological concordance between Shank3-mutant primates and human ASD cases provides compelling evidence of the gene’s contributory role in the disorder, enhancing the translational potential for therapeutic strategies aimed at ameliorating synaptic and behavioral anomalies associated with Shank3 dysregulation.

SCN2A Mutation Reversal

The SCN2A gene, encoding a voltage-gated sodium channel vital for the regulation of neuronal excitability, has been implicated in ASD and related neurodevelopmental disorders. Recent advancements in genomic editing technologies, notably CRISPR-Cas9, have facilitated the reversal of autism-associated mutations in SCN2A within murine models. This pioneering approach has demonstrated the feasibility of correcting pathogenic mutations, restoring physiological function to the affected sodium channels, and ameliorating neurobehavioral deficits in these models. The successful reversal of SCN2A mutations illuminates a path towards the development of gene-editing-based therapeutics, offering a paradigm shift in the treatment of ASD. The implications of this research are profound, suggesting that direct correction of the genetic aberrations underlying ASD can restore normative neural function and behavior. Consequently, this body of work not only advances our understanding of the molecular mechanisms contributing to ASD but also heralds a new era of genetic therapies aimed at the core etiological factors of the disorder.

Conclusion

In the expansive realms of neuro-oncology and neurogenetics, this comprehensive review meticulously dissects and synthesizes the intricate genetic landscapes underpinning both brain tumors—including glioblastoma, meningioma, and medulloblastoma—and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), a pivotal condition within the spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders. Central tothis exploration is the role of microRNAs (miRNAs), those diminutive yet potent non-coding RNA molecules that have emerged as quintessential regulators of gene expression, impacting a multitude of biological processes crucial to both oncogenesis and neurodevelopment. The advent of genetic engineering technologies, most notably CRISPR-Cas9, represents a seismic shift in our ability to not just understand but actively manipulate the genetic fabric underlying these conditions. This tool has afforded us the precision, efficiency, and flexibility to edit the genome of living organisms, heralding a new era of medical science where genetic disorders are corrected at their source. This review traverses the potential of these technologies to revolutionize disease modeling, facilitate functional genomic studies, and foster the development of targeted therapeutics, all within the broader vision of precision medicine. Through rigorous comparative genetic analysis, this study unveils shared genetic mutations and miRNA expressions bridging the seemingly disparate worlds of brain tumors and ASD. It casts a spotlight on the potential of genetic insights to not only amplify our understanding of the genetic and epigenetic mechanisms at play but also to harness these insights for groundbreaking diagnostic and therapeutic innovations. The role of genetic engineering and specific cases of gene editing are scrutinized, as is the transformative potential of CRISPR-Cas9 technology in crafting precision medicine and personalized treatment strategies. This review navigates through the convoluted pathways of cellular growth and differentiation, shedding light on the dual implications of miRNAs in the uncontrolled cellular proliferation characteristic of brain tumors and the dysregulated neurodevelopment associated with autism. It stands as a testament to the power of genetic engineering and miRNA research in unraveling the complexities of neurogenetic and neuro-oncological conditions. As we stand on the precipice of a new frontier in medical science, this review underscores the imperative of continued innovation and research. The future trajectory of the field, buoyed by advancements in genomic research and genetic engineering, promises a vista where more targeted and effective therapeutic strategies are not just envisioned but realized. The journey from genetic insight to clinical intervention remains fraught with challenges, yet the potential to transform patient care and treatment paradigms in neuro-oncology and neurogenetics remains unparalleled. This review, in charting this journey, aims to inspire further exploration, innovation, and a deeper engagement with the genetic undercurrents that define these complex conditions, paving the way for a future where the boundaries of what is possible are continually expanded.

References

- Risacher SL, Saykin AJ. Neuroimaging Advances in Neurologic and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurotherapeutics 18 (2021): 659–660.

- Ahmed MR, et al. Neuroimaging and Machine Learning for Dementia Diagnosis: Recent Advancements and Future Prospects. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng 12 (2019): 19–33.

- Soliman A, et al. Adopting Transfer Learning for Neuroimaging: A Comparative Analysis with a Custom 3D Convolution Neural Network Model. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 22 (2022): 318.

- Mishra R, Li B. The Application of Artificial Intelligence in the Genetic Study of Alzheimer’s Disease. Aging Dis 11 (2020): 1567–1584.

- Kazemzadeh K, et al. Advances in Artificial Intelligence, Robotics, Augmented and Virtual Reality in Neurosurgery. Front Surg 10 (2023): 1241923.

- Mofatteh M. Neurosurgery and Artificial Intelligence. AIMS Neurosci 8 (2021): 477–495.

- de la Torre-Ubieta L, et al. Advancing the Understanding of Autism Disease Mechanisms through Genetics. Nat Med 22 (2016): 345–361.

- Yen C, Lin CL, Chiang MC, et al. Exploring the Frontiers of Neuroimaging: A Review of Recent Advances in Understanding Brain Functioning and Disorders. Life 13 (2023): 1472.

- Khaliq F, Oberhauser J, Wakhloo D, et al. Decoding Degeneration: The Implementation of Machine Learning for Clinical Detection of Neurodegenerative Disorders. Neural Regen Res 18 (2023): 1235–1242.

- Famitafreshi H, Karimian M. Overview of the Recent Advances in Pathophysiology and Treatment for Autism. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 17 (2018): 590–594.

- Matthews JS, Adams JB. Ratings of the Effectiveness of 13 Therapeutic Diets for Autism Spectrum Disorder: Results of a National Survey. J Pers Med 13 (2023): 1448.

- Muhle R, et al. The Genetics of Autism. Pediatrics 113 (2004): e472–e486.

- Sachdeva P, et al. Potential Natural Products for the Management of Autism Spectrum Disorder. iBrain 8 (2022): 365–376.

- Bai J, et al. Adult Glioma WHO Classification Update, Genomics, and Imaging: What the Radiologists Need to Know. Top Magn Reson Imaging 29 (2020): 71–82.

- Colucci-D'Amato L, et al. Neurotrophic Factor BDNF: Physiological Functions and Therapeutic Potential in Depression, Neurodegeneration and Brain Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 21 (2020): 7777.

- Bloem BR, et al. Parkinson’s Disease. Lancet 397 (2021): 2284–2303.

- Emerson NE, Swarup V. Proteomic Data Advance Targeted Drug Development for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biol Psychiatry 93 (2023): 754–755.

- García JC, Bustos RH. The Genetic Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases and Therapeutic Perspectives. Brain Sci 8 (2018): 222.

- Bertram L, Tanzi RE. The Genetic Epidemiology of Neurodegenerative Disease. J Clin Invest 115 (2005): 1449–1457.

- Ruffini N, et al. Common Factors in Neurodegeneration: A Meta-Study Revealing Shared Patterns on a Multi-Omics Scale. Cells 9 (2020): 2642.

- Mateos-Pérez JM, et al. Structural Neuroimaging as Clinical Predictor: A Review of Machine Learning Applications. Neuroimage Clin 20 (2018): 506–522.

- Zhou SK, et al. A Review of Deep Learning in Medical Imaging: Imaging Traits, Technology Trends, Case Studies with Progress Highlights, and Future Promises. Proc IEEE 109 (2021): 820–838.

- Van Deerlin VM. The Genetics and Neuropathology of Neurodegenerative Disorders: Perspectives and Implications for Research and Clinical Practice. Acta Neuropathol 124 (2012): 297–303.

- Raichle ME, Mintun MA. Brain Work and Brain Imaging. Annu Rev Neurosci 29 (2006): 449–476.

- Genovese A, Butler MG. The Autism Spectrum: Behavioral, Psychiatric and Genetic Associations. Genes 14 (2023): 677.

- Albert FW, Kruglyak L. The Role of Regulatory Variation in Complex Traits and Disease. Nat Rev Genet 16 (2015): 197–212.

- Andersen EC, Shimko TC, Crissman JR, et al. A Powerful New Quantitative Genetics Platform Combining Caenorhabditis elegans High-Throughput Fitness Assays with a Large Collection of Recombinant Strains. G3 (Bethesda) 5 (2015): 911–920.

- Artal-Sanz M, Tavernarakis N. Prohibitin and mitochondrial biology. Trends Endocrinol Metab 20 (2009): 394–401.

- Abel O, Powell JF, Andersen PM, et al. ALSoD: A user-friendly online bioinformatics tool for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Hum Mutat (2012).

- Breitner JC. Clinical genetics and genetic counseling in Alzheimer disease. Annals of internal medicine 115 (1991): 601–606.