Frailty Screening in Major Cardiac Surgical Patients. Which Tool is Better for Predicting Poor Outcomes?

Article Information

Myriel M. López Tatis1*, Carlos Amorós Rivera2, Francisco Javier López Rodríguez3, María Elena Arnaiz García3, Ramón Adolfo Arévalo-Abascal3, Ana María Barral Varela3, María Teresa Merino Vicente3, José María González Santos3

1Mater Private Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

2Mater Misericordiae University Hospital. Dublin, Ireland

3Cardiac Surgery Department, University Hospital of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain

*Corresponding Author: Myriel M. López Tatis. Mater Private Hospital, Eccles Street, Dublin 7, Ireland

Received: 14 November 2022; Accepted: 21 November 2022; Published: 01 December 2022

Citation: Myriel M. López Tatis, Carlos Amorós Rivera, Francisco Javier López Rodríguez, María Elena Arnaiz García, Ramón Adolfo Arévalo- Abascal, Ana María Barral Varela, María Teresa Merino Vicente, José María González Santos. Frailty Screening in Major Cardiac Surgical Patients. Which Tool is Better for Predicting Poor Outcomes?. Journal of Surgery and Research 5 (2022): 607-617.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Objective: To analyse the relationship between the degree of frailty and the risk of presenting poor short-term outcomes.

Methods: Observational cohort study of the population ≥70 years of age undergoing elective and high-priority major cardiac surgery at our hospital. A total of 232 consecutive patients were enrolled in Salamanca University Hospital from October 2017-December 2019 This cohort study of 232 patients prospectively compared the results of the FRAIL questionnaire and the Fried Phenotype Criteria (FPC) and retrospectively adapted these tools based on the characteristics and confounding factors found in our sample. The individual items comprising the multi-item scales were then independently analysed using logistic regressions.

Results: Frailty was associated with increased mortality, although the differences were not significant. Standardizing the FPC improved its ability to identify frail patients (p=0.027). Scores with both original tools were associated with a prolonged postoperative stay (p≤0.05). Additionally, a positive result on the FRAIL questionnaire was associated with a higher number of complications (p=0.025). In our study, the predictive capacity emerged from specific items: grip strength, gait speed, illness, and resistance. We united these items with the severity of pulmonary hypertension to create a specific frailty scale for cardiac surgery, and the scores were significantly associated with a combined endpoint, containing death, prolonged stay, and/or presenting ≥3 complications (p=0.011).

Conclusions: The results indicated that frailty determined by either of the original tools was associated with worse results after cardiac surgery. Likewise, milder degrees of frailty, which we call pre-frailty, can also anticipate poor o

Keywords

Cardiac surgery, Frailty, FPC, Grip strength, Gait speed

Cardiac surgery articles; Frailty articles; FPC articles; Grip strength articles, Gait speed articles

Cardiac surgery articles Cardiac surgery Research articles Cardiac surgery review articles Cardiac surgery PubMed articles Cardiac surgery PubMed Central articles Cardiac surgery 2023 articles Cardiac surgery 2024 articles Cardiac surgery Scopus articles Cardiac surgery impact factor journals Cardiac surgery Scopus journals Cardiac surgery PubMed journals Cardiac surgery medical journals Cardiac surgery free journals Cardiac surgery best journals Cardiac surgery top journals Cardiac surgery free medical journals Cardiac surgery famous journals Cardiac surgery Google Scholar indexed journals Frailty articles Frailty Research articles Frailty review articles Frailty PubMed articles Frailty PubMed Central articles Frailty 2023 articles Frailty 2024 articles Frailty Scopus articles Frailty impact factor journals Frailty Scopus journals Frailty PubMed journals Frailty medical journals Frailty free journals Frailty best journals Frailty top journals Frailty free medical journals Frailty famous journals Frailty Google Scholar indexed journals Grip strength articles Grip strength Research articles Grip strength review articles Grip strength PubMed articles Grip strength PubMed Central articles Grip strength 2023 articles Grip strength 2024 articles Grip strength Scopus articles Grip strength impact factor journals Grip strength Scopus journals Grip strength PubMed journals Grip strength medical journals Grip strength free journals Grip strength best journals Grip strength top journals Grip strength free medical journals Grip strength famous journals Grip strength Google Scholar indexed journals Gait speed articles Gait speed Research articles Gait speed review articles Gait speed PubMed articles Gait speed PubMed Central articles Gait speed 2023 articles Gait speed 2024 articles Gait speed Scopus articles Gait speed impact factor journals Gait speed Scopus journals Gait speed PubMed journals Gait speed medical journals Gait speed free journals Gait speed best journals Gait speed top journals Gait speed free medical journals Gait speed famous journals Gait speed Google Scholar indexed journals Salamanca University Hospital articles Salamanca University Hospital Research articles Salamanca University Hospital review articles Salamanca University Hospital PubMed articles Salamanca University Hospital PubMed Central articles Salamanca University Hospital 2023 articles Salamanca University Hospital 2024 articles Salamanca University Hospital Scopus articles Salamanca University Hospital impact factor journals Salamanca University Hospital Scopus journals Salamanca University Hospital PubMed journals Salamanca University Hospital medical journals Salamanca University Hospital free journals Salamanca University Hospital best journals Salamanca University Hospital top journals Salamanca University Hospital free medical journals Salamanca University Hospital famous journals Salamanca University Hospital Google Scholar indexed journals Pulmonary hypertension articles Pulmonary hypertension Research articles Pulmonary hypertension review articles Pulmonary hypertension PubMed articles Pulmonary hypertension PubMed Central articles Pulmonary hypertension 2023 articles Pulmonary hypertension 2024 articles Pulmonary hypertension Scopus articles Pulmonary hypertension impact factor journals Pulmonary hypertension Scopus journals Pulmonary hypertension PubMed journals Pulmonary hypertension medical journals Pulmonary hypertension free journals Pulmonary hypertension best journals Pulmonary hypertension top journals Pulmonary hypertension free medical journals Pulmonary hypertension famous journals Pulmonary hypertension Google Scholar indexed journals European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation articles European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation Research articles European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation review articles European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation PubMed articles European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation PubMed Central articles European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation 2023 articles European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation 2024 articles European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation Scopus articles European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation impact factor journals European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation Scopus journals European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation PubMed journals European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation medical journals European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation free journals European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation best journals European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation top journals European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation free medical journals European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation famous journals European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation Google Scholar indexed journals receiver operating curve articles receiver operating curve Research articles receiver operating curve review articles receiver operating curve PubMed articles receiver operating curve PubMed Central articles receiver operating curve 2023 articles receiver operating curve 2024 articles receiver operating curve Scopus articles receiver operating curve impact factor journals receiver operating curve Scopus journals receiver operating curve PubMed journals receiver operating curve medical journals receiver operating curve free journals receiver operating curve best journals receiver operating curve top journals receiver operating curve free medical journals receiver operating curve famous journals receiver operating curve Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

Glossary abbreviations and acronyms

CVD: cardiovascular disease

FRAIL: Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illnesses, Loss of weight

FPC: Frailty Phenotype Criteria

STS score: Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score

EuroSCORE: European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation

BMI: Body mass Index

PHT: Pulmonary hypertension

ROC: receiver operating curve

CI: correlation coefficient

NYHA functional Class

RR: Relative Risk

S-FPC: Standandized Frailty Phenotype Criteria

FCS : Frailty in Cardiac Surgery Scale

Introduction

Frailty is a state of vulnerability to stressors that increases the risk of death, dependency, postoperative complications, and institutionalization [1]. The fastest growing population subgroup in Spain is people ≥80 years old [2]. Similar findings have been observed in the Western world. The growth of the elderly population increases the incidence of frailty and accelerates its evolution through a higher prevalence of low physical activity, and cardiovascular disease [3]. Frailty is a strong predictor of poor outcomes following cardiovascular interventions [3,4]. It has been shown that the most common methods for risk prediction in cardiac surgery -STS-score, EuroSCORE, and EuroSCORE II- are not the most accurate predictors of mortality in frail patients and overestimate the risk of high-risk patients [3,5-7]. Confounding factors have made it difficult to identify appropriate screening tools for frailty since many of the same risk factors apply to cardiovascular disease, frailty, and poor results after intervention [8-22]. Other authors have concluded that standardization of screening tools to the selected population improves the ability to detect frail or pre-frail individuals and their resultant risks [12]. Standardization of the FPC has been shown to improve its ability to predict poor results in cardiovascular risk assessment scores [13]. On the other hand, no study, to the best of our knowledge, has applied this method to predict poor results after cardiac surgery.

The intimate link between frailty and cardiovascular disease [8-22] caused that the populations in which these tools were developed in, contained a high prevalence of cardiovascular disease within their samples. Some of the characteristics of the frailty phenotype, like fatigue, occur frequently in cardiovascular patients. The probability for information overlaps and confusion between frailty and cardiovascular disease as very likely. Hence the difficulty for interpreting the results of these tools when applied to cardiovascular patients. What are the tools measuring? Frailty or the manifestation of cardiovascular symptoms that are potentially reversable? [20]

Available tests [21] for frailty typically conform to one of two variants that determine frailty differently. There is the “phenotype” variant, and the “accumulation of deficits” variant, which defines frailty as the accumulation of different pathological conditions. This type of tool is similar to our standard tool for risk assessment, the EuroSCORE II. In it we can find multiple conditions, like vasculopathy, that increase the risk of our patients. The possibility of overlapping information made these tests less interesting for our study.

The “phenotype” variant and its description of frailty as manifesting as “slowness, weakness, low physical activity…”, made tools like the FPC and the FRAIL Questionnaire far more appealing for trying to find the missing link between the observed mortality and the expected mortality by EuroSCORE II.

Main objective

To analyse the relationship between the degree of frailty determined by two well-known screening tools, the FRAIL questionnaire, and the FPC, and the risk of presenting poor short-term outcomes after major cardiac surgery, including death, prolonged stay, complications, and a combination of all endpoints.

Secondary objectives

To investigate the relationships between frailty and other variables obtained from our population to determine which confounding factors can alter the interpretation of the frailty classification.

To adapt these original screening tools to the characteristics and confounding factors found in our sample and analyse whether the results were improved.

Patients and Methods

Study design

This was an observational cohort study of the population ≥70 years of age undergoing elective and high-priority major cardiac surgery at our hospital. Emergencies, patients with surgeries in the previous 3 months or unable to perform the tests were excluded.

Setting

After the patients were accepted for surgery by the cardiac surgery department, they were evaluated by a geriatrician at the preoperative outpatient consultation or the ward. Following previous findings from other authors, we retrospectively standardized the objective measurements used in the FPC, namely, gait speed and grip strength, once our study had concluded and all our patients had either presented an outcome or had been discharged [12,13]. This corrected for the skew towards a younger age and proportionally less cardiovascular disease seen in the original cohort studied by Fried et. al. in 2001 [11].

Similar to Fried et al. [11], we observed differences in gait speed at the 25th percentile for height, in both sexes. In contrast, we found lower speeds in the tallest male subgroup. The worst results in gait speed in this subgroup were explained by a worse New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, compared to other subgroups (p=0.005). On the other hand, we also observed differences in the subject’s grip strength at the 33rd and 66th percentiles for Body Mass Index (BMI), in both sexes. Detailed cut-offs for our standardization can be seen in table 1.

|

Height |

Cut-off values |

||

|

Gait |

Male |

>162 cm |

0.72 m/s |

|

<162 cm |

0.81 m/s |

||

|

Female |

>150 cm |

0.62 m/s |

|

|

< 150 cm |

0.57 m/s |

||

|

Body mass index |

Cut-off values |

||

|

Grip strength |

Male |

<26 |

24.6 kg |

|

26-29 |

26.5 kg |

||

|

>29 |

28.3 kg |

||

|

Female |

<25 |

15.3 kg |

|

|

25-30 |

13.2 kg |

||

|

>30 |

12.5 kg |

||

Table 1: Standardization of the Fried phenotype criteria.

This process resulted in a stricter FPC scale, the Standardized Fried Phenotype Criteria (S-FPC), which reclassified 18 (34.6%) patients previously considered frail as pre-frail. Similarly, 16 (12.2%) patients from the original pre-frail group improved their classification to robust. Movements in the opposite direction on the scale were much rarer and observed with only 4 (1.7%) patients.

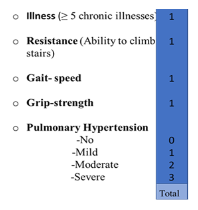

Based on the retrospective analysis, we also designed a scale, called the Frailty in Cardiac Surgery (FCS) scale, tailored for cardiovascular patients. It is composed of the 4 items less affected by confusion (illness, resistance, gait speed, and grip strength), and the degree of pulmonary hypertension (PHT) severity (none: ≤25 mmHg, mild: 25-35 mmHg, moderate: 35-55 mmHg, or severe: ≥55 mmHg). The scale has a range from 0-7 points. A cut-off for frailty at ≥4 points was established after analysis of the receiver operating curve (ROC), using the combined endpoint as reference, but also maintained its qualities when its different components were selected. This value presents the highest Youden’s J, (0.2, 95% CI: 0.07-0.32), which is suboptimal and may be underestimated due to our low incidence of adverse outcomes. However, it offers a high negative predictive value: 71% (95% CI: 65.5-84.4), an important benefit considering that a false negative test would be more detrimental than a false positive result, as it would entail an invasive surgery on a high-risk patient. As with other scales, zero means robust and intermediate degrees (1-3) are considered pre-frail. A combined endpoint was created, incorporating the occurrence of death, prolonged postoperative stay (≥15 days), and/or presenting ≥3 in-hospital complications. All patients' intraoperative and postoperative data were prospectively collected during hospitalization. The patients were screened for frailty after they were accepted for surgery, to reduce selection bias from the surgeons. There was a loss of data that occurred, but only with the following variables: albumin (12.5%), vitamin D (31%), and protein C (14.2%).

Variables

FRAIL questionnaire

The patient was interviewed regarding the existence and frequency of fatigue, their ability to climb stairs without resting, their ability to walk one block, the number of illnesses that they are presenting with (five illnesses grants one point), and finally, undesired loss of weight (one point if ≥5 kg in a year). A score of zero means robust; 1-2, pre-frail; and ≥3, frail [8,9].

Fried phenotype criteria

Frailty was defined as a clinical syndrome in which ≥3 of the following criteria were present: unintentional weight loss (5 kg or 5% of body weight in the previous year), self-reported exhaustion, weakness (grip strength of the dominant hand using an electronic Jamar Plus+ 12-0604™ Digital Dynamometer, adjusted for sex and BMI), slow walking speed (adjusted by sex and height), and low physical activity (according to the kilocalories expended per week for each sex). This scale has been previously validated in the Spanish population [10,11].

Outcome data

The endpoints of the study were in-hospital mortality, complications, prolonged postoperative stay (≥15 days), and their combination.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed using IBM™ SPSS™ Statistics V21.0.0.0 and Epidat 3.1. Characteristics of the patients with or without frailty were compared using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and Mann-Whitney test for independent samples for continuous variables. Correlations were established using Kendall’s Tau-b. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered significant. Independent predictors of mortality, prolonged stay, complications, and their combination were analysed using binary logistic regressions. Models’ adjustments were evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow tests.

Study size

We estimated that a minimum sample size of 875 subjects was required to perform hypothesis contrast tests (p=0.05 and 80-90% power) in our cohort study, considering that a 5% mortality risk for the unexposed and 10% for the exposed has been reported in the literature [4-6]. This size could not be obtained in our recruitment period, and this should be considered when analyzing associations between mortality and the original tests.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics can be seen in table 2. We observed that the FRAIL questionnaire classified 109(47%) patients as frail, while the FPC considered only 52(22.4%) patients to have frailty. The classification varied widely according to the tool used, although, the FRAIL questionnaire and the FPC scores were positively correlated with each other (correlation coefficient: 0.6; p=0.001), and statistically associated (p=0.001).

|

Age (years) |

76 (73-79) |

|

Male |

143 (61.6%) |

|

Hypertension |

173 (74.6%) |

|

Diabetes |

82 (35.3%) |

|

High cholesterol |

136 (58.6%) |

|

Ex-smoker |

80 (34.5%) |

|

Active smoking |

17 (7.3%) |

|

Atrial fibrillation |

119 (51.3%) |

|

Ejection fraction (%) |

60 (53.3-60) |

|

Pulmonary Hypertension ≥ moderate |

95 (40.9%) |

|

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

19 (8.2%) |

|

Chronic renal insufficiency |

74 (31.9%) |

|

Functional class ≥III |

81 (34.9%) |

|

EuroSCORE (%) |

7 (4.8-10.7) |

|

EuroSCORE II (%) |

3.6 (2.1-5.9) |

|

Obesity |

58 (25%) |

|

Isolated coronary artery bypass graft |

82 (35.3%) |

|

Isolated aortic valve surgery |

138 (59.5%) |

|

Isolated mitral valve surgery |

111 (47.8%) |

|

Isolated tricuspid valve surgery |

82 (35.3%) |

|

Replacement of the aorta |

15 (6.5%) |

|

Combined procedures |

147 (63.4%) |

Table 2: Patient characteristics

We determined that the FPC scores had no correlations with our standard risk-stratification scales. The FRAIL questionnaire scores did show a significant positive correlation with both the EuroSCORE and EuroSCORE II (correlation coefficient: 0.15 and 0.11, respectively) (p≤0.05).

Table 3 describes the preoperative characteristics of the patients with and without frailty, based on the different frailty screening tools. We can observe that female sex, PHT, and obesity were associated with frailty as determined by all methods. Otherwise, the FRAIL questionnaire scores were significantly more influenced by cardiovascular disease and NYHA functional class than the FPC scores. This influence is shown again with the significant association between the FRAIL questionnaire scores and mitral and tricuspid surgery. Although, this did not translate into a higher mortality in mitral patients considered frail by The FRAIL Questionnaire (p ≥0.05). On the contrary, we observed that in patients affected by aortic disease, being considered frail by the S-FPC or the FCS scale, was in fact associated to higher mortality rate (p= 0.034 and p = 0.016, respectively).

|

Statistical associations to frailty |

|||||||||

|

FRAIL questionnaire |

Fried phenotype criteria |

Standardized-FPC |

|||||||

|

Frail |

Non-frail |

P-value |

Frail |

Non-frail |

P-value |

Frail |

Non-frail |

P-value |

|

|

Age (years) |

77 (73-79) |

75 (73-78) |

0.8 |

77 (73.3-80) |

76 (73-78) |

0.1 |

78 (73.3-80) |

76 (73-78) |

0.07 |

|

Female (%) |

48.6 |

29.3 |

0.03 |

65.4 |

30.6 |

0.001 |

55.6 |

35.2 |

0.02 |

|

Hypertension (%) |

80.7 |

69.1 |

0.05 |

75 |

74.4 |

1 |

80.6 |

73.5 |

0.4 |

|

Diabetes (%) |

40.4 |

30.9 |

0.2 |

36.5 |

35 |

0.9 |

44.4 |

33.7 |

0.3 |

|

High cholesterol (%) |

54.1 |

62.6 |

0.2 |

51.9 |

60.6 |

0.3 |

52.8 |

59.7 |

0.5 |

|

History of smoking (%) |

38.5 |

44.7 |

0.3 |

26.9 |

46.1 |

0.06 |

27.8 |

44.4 |

0.2 |

|

Body mass Index |

27.8 (25-31.1) |

27 (24.2-29.2 |

0.02 |

28.2 (25-31.5) |

27.4 (24.4-29.4) |

0.01 |

26.8 (23.7-31) |

27.6 (24.9-29.8) |

0.7 |

|

COPD (%) |

10.1 |

6.5 |

0.3 |

9.6 |

7.8 |

0.8 |

8.3 |

8.2 |

1 |

|

Renal failure (%) |

33 |

30.9 |

0.8 |

19.2 |

35.6 |

0.02 |

27.8 |

32.7 |

0.7 |

|

Ejection Fraction (%) |

60 (55-60) |

60 (52-60) |

0.6 |

60 (56.3-60) |

60 (51.3-60) |

0.09 |

60 (56.3-60) |

60 (52-60) |

0.1 |

|

Atrial fibrillation |

61.5 |

42.3 |

0.004 |

53.8 |

50.6 |

0.8 |

66.7 |

48.5 |

0.05 |

|

(%) |

|||||||||

|

Functional class ≥III (%) |

44.9 |

26 |

0.004 |

46.1 |

31.6 |

0.06 |

50 |

32.2 |

0.05 |

|

Pulmonary hypertension ≥ moderate (%) |

47.7 |

34.9 |

0.038 |

52 |

37.7 |

0.07 |

58.3 |

37.8 |

0.02 |

|

EuroSCORE (%) |

7.2 (5.5-11.2) |

6.5 (4.8-10.3) |

0.1 |

7 (5.1-11.6) |

6.8 (4.8-10.4) |

0.5 |

7.8 (5.1-12.5) |

6.7 (4.8-10.3) |

0.2 |

|

EuroSCORE II (%) |

3.8 (2.5-7.4) |

3.2 (1.9-5.3 |

0.011 |

3.5 (2.5-7.3) |

3.6 (2-5.6) |

0.3 |

4.9 (2.6-7.8) |

3.5 (2-5.4) |

0.01 |

|

Haemoglobin (g/dL) |

13.5 ± 1.6 |

13.9 ± 1.6 |

0.2 |

13.3 ± 1.6 |

13.8 ± 1.6 |

0.03 |

13.2 ± 1.6 |

13.8 ± 1.6 |

0.04 |

|

Albumin (g/dL) |

4.2 (4-4.5) |

4.4 (4.1-4.6) |

0.03 |

4.2 (4-4.5) |

4.3 (4-4.6) |

0.1 |

4.2 (3.9-4.4) |

4.3 (4-4.6) |

0.4 |

|

Vitamin D (ng/ml) |

17.2 (12.2-22.9) |

17.4 (12.8-22.9) |

0.5 |

17.4 (12-23.6) |

17.3 (12.3-22.7) |

0.9 |

17 (11.7-21) |

17.4 (12.5-22.9) |

0.5 |

|

Protein c (mg/l) |

0.27 (0.12-0.81) |

0.22 (0.11-0.58) |

0.3 |

0.37 (0.14-1) |

0.22 (0.1-0.62) |

0.7 |

0.31 (0.15-0.93) |

0.24 (0.11-0.62) |

0.2 |

|

Isolated aortic valve (%) |

56.9 |

61.8 |

0.5 |

57.7 |

60 |

0.9 |

52.8 |

60.7 |

0.5 |

|

Isolated mitral valve (%) |

56 |

40.7 |

0.025 |

53.8 |

46.1 |

0.3 |

58.3 |

45.9 |

0.2 |

|

Isolated tricuspid valve (%) |

42.2 |

29.3 |

0.05 |

44.2 |

32.8 |

0.1 |

47.2 |

33.2 |

0.1 |

|

Isolated coronary bypass (%) |

35.8 |

35 |

1 |

30.8 |

36.7 |

0.5 |

36.1 |

35.2 |

1 |

|

Aorta (%) |

5.5 |

7.3 |

0.6 |

1.9 |

7.8 |

0.2 |

0 |

7.7 |

0.1 |

|

Combined procedures (%) |

71.6 |

56.1 |

0.02 |

73.1 |

60.6 |

0.1 |

75 |

61.2 |

0.1 |

|

Operative mortality (%) |

7.3 |

4.1 |

0.4 |

9.6 |

4.4 |

0.2 |

13.9 |

4.1 |

0.034 |

|

Postoperative stay |

11 (8-16.5) |

9 (8-14) |

0.05 |

11 (8-17.7) |

10 (8-14) |

0.2 |

11 (8-16.7) |

10 (8-14.7) |

0.3 |

Table 3: Statistical associations to frailty. FPC: Fried phenotype criteria. COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Mortality

In-hospital mortality occurred in 13(5.6%) patients. This was higher than the expected mortality by EuroSCORE II (4.9%), but lower than the mortality expected by EuroSCORE (8.9%). The only independent predictor for mortality found by binary logistic regression was PHT, with a RR of 1.95 (95% CI: 1.17–3.26)(p=0.01), for every degree increase in severity. The patients with frailty determined by either scale showed higher mortality. Using the FRAIL questionnaire, mortality for the frail and non-frail groups was 7.3% vs 4.1%, respectively (p=0.39). Meanwhile, the FPC results were 9.6% vs 4.4%, respectively (p=0.17). However, our sample size was insufficient for determining significance.

Frailty determined by the standardized FPC (S-FPC) showed a higher incidence of mortality; 13.9% vs 4.1%; with a RR of 3.8 (95% CI: 1.16–12.33)(p=0.027), which was an improvement in the results obtained with the FPC. However, the influence of PHT on this association could not be evaluated using logistic regressions due to significant positive correlation between both variables (correlation coefficient: 0.12)(p= 0.04). Additionally, all other preoperative variables were consecutively added to the model one-by-one. In all cases the model was well adjusted (Hosmer-Lemeshow ≥0.05). When the NYHA class was introduced into the model, it was found to be a confounding factor with all other items except weight loss (p≤0.05).

When all 5 items of the S-FPC were independently analysed, we found that all the associations with mortality came from only one of the items, namely, standardized grip strength. This association was not affected by the introduction of PHT, which made grip strength an independent predictor of mortality, with a RR of 3.74 (95% CI: 1.15–12.19)(p=0.028). Pre-frailty was associated to mortality only if the point obtained came from standardized grip strength.

Postoperative stay

The median postoperative stay was 10 days (interquartile range 8-15 days). A total of 61(26.3%) patients had a prolonged postoperative stay of ≥15 days. Being considered frail by both the FRAIL questionnaire and the FPC was found to be an independent predictor of prolonged postoperative stay, as shown in table 4.

|

p-value |

RR |

95% CI |

||

|

Inferior |

Superior |

|||

|

History of smoking |

0.001 |

2.6 |

1.6 |

4.2 |

|

Mitral valve surgery |

0.001 |

3.1 |

1.6 |

6.2 |

|

FRAIL questionnaire |

0.024 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

3.9 |

|

Fried phenotype criteria |

0.017 |

2.3 |

1.1 |

4.7 |

|

Resistance |

0.03 |

2.3 |

1.4 |

6.9 |

|

Illness |

0.007 |

3.1 |

1.01 |

5.1 |

|

Gait speed |

0.01 |

2.4 |

1.1 |

5.1 |

|

Standardized gait speed |

0.037 |

2.8 |

1.3 |

6.2 |

|

Standardized grip strength |

0.025 |

0.34 |

0.13 |

0.87 |

Table 4: Independent predictors of prolonged postoperative stay

When we independently analysed all 5 items from the FRAIL questionnaire with logistic regressions, we observed that both resistance, and illness were independent predictors of prolonged postoperative stay. When the 5 items from the FPC were separately analysed, gait speed, both before and after standardization, was shown to be an independent predictor of prolonged stay.

The model generated with these individual variables shows excellent adjustment (Hosmer-Lemeshow: 0.9). If pre-frailty emerged from these selected items, it predicted the risk of a prolonged recovery.

Complications

Complications are adverse events attributable to the cardiac intervention that affect different systems and that can prolong the time of recovery and/or provoke death. A total of 55(23.7%) patients presented ≥3 complications. The item of illness, and obesity were both independent predictors of presenting with ≥3 complications. Obtaining a point based on illness (pre-frailty) presented a RR of 2.2 (95% CI: 1.05-4.8) (p=0.05) while obesity showed a RR of 2.3 (95% CI: 1.2-4.5)(p=0.013)(Hosmer-Lemeshow: 0.84). The incidence of complications in our sample is shown in table 5. The independent predictors for specific complications are shown in table 6.

|

Complications |

|

|

Infections |

36 (15.5%) |

|

Pacemaker |

16 (6.9%) |

|

Atrial fibrillation |

61 (26.3%) |

|

Respiratory |

42 (18.1%) |

|

Neurological |

7 (3%) |

|

Vascular |

2 (0.9%) |

|

Mesenteric ischemia |

2 (0.9%) |

|

Myocardial infarction |

4 (1.7%) |

|

Low cardiac output |

21 (9.1%) |

|

ECMO |

4 (1.7%) |

|

Renal insufficiency |

65 (28%) |

|

Wound dehiscence |

9 (3.9%) |

|

Bleeding / cardiac tamponade |

11 (4.7%) |

|

Pericardial effusion |

3 (1.3%) |

|

Reintervention |

18 (7.8%) |

Table 5: Incidence of complications in our sample. ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

|

Variable |

RR |

95% CI |

||

|

Inferior |

Superior |

|||

|

Infections |

Active smoking (p=0,025) |

2.3 |

1.1 |

4.8 |

|

Ejection Fraction (%) (p=0,012) |

0.93 |

0.88 |

0.98 |

|

|

High Cholesterol |

2.8 |

1.1 |

7.4 |

|

|

(p=0,037) |

||||

|

Pacemaker |

FRAIL |

7.1 |

1.6 |

31.5 |

|

Questionnaire |

||||

|

(p=0,01) |

||||

|

Respiratory |

Smoking |

2.5 |

1.3 |

5 |

|

(p=0,007) |

||||

|

Coronary surgery |

4.8 |

1.7 |

13.9 |

|

|

(p=0,004) |

||||

|

Renal Insufficiency |

Diabetes (p=0,007) |

2.9 |

1.3 |

6.2 |

|

Mitral surgery (p=0,026) |

4.4 |

1.2 |

16.3 |

|

Table 6: Independent predictors of complications.

Combined endpoint

Eighty-five (36.6%) patients presented the combined endpoint. The scores on neither of the original tests, the FRAIL questionnaire nor the FPC were significantly associated with the combined endpoint. The association with S-FPC scores did not reach statistical significance either.

The Frailty in Cardiac Surgery Scale (FCS)

A total of 93(40.1%) patients were classified as frail using our scale. The FCS showed a statistically significant association with the combined endpoint (p=0.011), and each component (p≤0.05). Each point obtained in the FCS scale carried a RR of 1.4 (95% CI: 1.1-1.7) for presenting with the combined endpoint. The results were the same when the standardized items were utilized. The association was not altered by the addition of confounding factors including 15 other preoperative variables (Hosmer-Lemeshow: 0.9). The regression coefficient remained significant after a 10,000-sample bootstrap (Regression coefficient: 0.266, typical error: 0.09, 95% CI: 0.11-0.45, p=0.002). Supplementary figure 1 explains the items of the scale and the pointing algorithm.

Figure 1: Pointing algorithm for the frailty in cardiac surgery scale. It includes four degrees for the pulmonary hypertension item. Four points is considered frail.

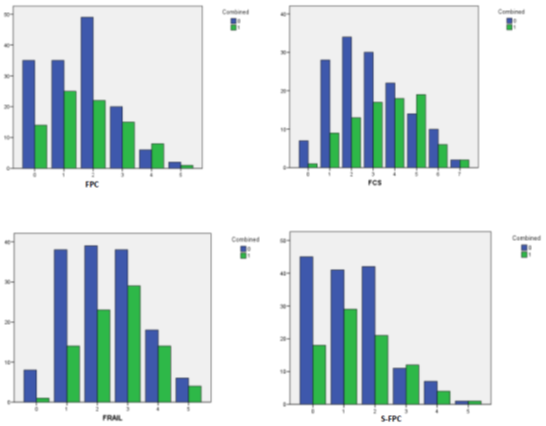

This scale was retrospectively developed using binary logistic regressions to identify which items were less influenced by confounding factors in their relationships with the different components of the combined endpoint. The scale showed suboptimal discrimination (AUC: 0.63). Although, it showed excellent calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow: 0.9) (Observed/expected risk: 0.91). Figure 2 shows all ROC curve data for the FCS. Obtaining four points in the scale classified the subjects as frail. In supplementary figure 2 you can observe how the proportion of patients that did not present with the combined endpoint decreases significantly around the selected cut-offs applied to each of the scales analysed. To summarize our findings, please observe figure 3, which outlines the items comprising the scales utilized and their associations to outcomes.

Figure 2: Group bar chart showing how the proportion of patients that didn’t present with the combined endpoint decreases significantly around the cut-offs that were selected for each test included in this study. FCS: Frailty in Cardiac Surgery scale. FPC: Fried Phenotype Criteria. S-FPC: Standardized Fried Phenotype Criteria. FRAIL: The FRAIL Questionnaire. 0: Didn’t present combined endpoint. 1: presented combined endpoint.

Figure 3: In our Visual Abstract we explain the flow diagram of the study. Additionally we show the individual items included inside each of the screening tools utilized and how the original tests were adapted to develop the adjusted tests using standardization and confounding factor analysis using logistic regressions. Finally, we show which scale is associated with which outcome using the relative risk obtained in multivariate analysis. FCS: Frailty in cardiac surgery scale. FPC: Fried Phenotype Criteria. S-FPC: Standardized Fried Phenotype Criteria. FRAIL: That FRAIL Questionnaire.

Discussion

Interpretation

This study was performed in an elective setting and in a European country with high life expectancy and universal healthcare. Results may not be extrapolated to urgent care, to different healthcare settings or countries with younger population. The methods of screening for frailty are diverse. Available approaches include multi-item tests and single parameter measurements [8-11,14,15]. Due to the close relationship between frailty and cardiovascular disease, multiple factors related to both may act as confounding factors when determining frailty [3,14-17]. There is no universally validated tool [18]. There are different types of frailty, primary or related to the aging process and sarcopenia, and secondary, to the natural history and complications of major pathologies [2-4,16,17]. Efforts must be made to distinguish the contribution of both to patients’ risk assessment. In our sample we have demonstrated PHT is intrinsically linked to frailty when measured by any screening tool. PHT was also found to be significantly associated to worse outcomes. These results point to PHT being a good marker of secondary cardiovascular frailty as it is usually a sign of chronic, prolonged cardiovascular disease, in the elective patient, with decrease of the patient´s activity and functional capacity. In our study, we found that scores on the FRAIL questionnaire were significantly influenced by cardiovascular risk factors, NYHA functional class, and cardiac pathologies. These pathologies included longstanding mitral valve disease, tricuspid involvement, and higher PHT severity. These factors are well-known to increase the risk associated with cardiac surgery, independent of frailty. This could be the reason why our data revealed significant correlations between FRAIL questionnaire scores and the results from the EuroSCORE and EuroSCORE II, indicating redundant information between the tests. We consider that this tool must be used carefully in cardiovascular disease when applied to determine risk, as the mortality associated to this scale was so similar to the unexposed group’s that a very large sample would be needed to demonstrate only minor differences. However, some of its items are independently associated with longer postoperative recovery and a higher risk of complications. Combined with its simplicity, these associations make it an interesting tool; that can be administered by any healthcare professional, or even through telemedicine. It may also identify patients with higher vulnerability that may benefit from optimization or prehabilitation.

We were unable to demonstrate a significant association between the FPC scores and mortality attributed to the small differences between the outcome of both cohorts. We believe this is also partially because the original Fried et. al cohort was younger and had a lower rate of cardiovascular disease than our cohorts [11]. Other authors have shown that cut-off values tend to be different in European populations, including Spain [12,13,19]. On the other hand, FPC demonstrated a significant association with a prolonged postoperative stay. The effect comes only from the results of gait speed, which shows that the single parameter approach may be viable to predict poor outcomes after surgery in the cardiovascular disease population, as has been previously demonstrated by other authors [19,20].

After standardizing our cut-off values for the FPC, we obtained a stricter scale, that had cut-offs closer to those found by others in our region [12,13] than to Fried et al. [11]. This increased the differences found between the cohorts’ mortality and reduced the needed sample size. Standardized grip strength was the only item of the test that was not influenced by the patient’s NYHA classification and emerged alongside PHT as an independent predictor for mortality. Low standardized grip strength shows a strong association with mortality in the early postoperative period, demonstrated by its “protective” effect on prolonged stay, and the loss of its significant association with mortality if we exclude the mortality observed in the first 24 hours after surgery from the analysis.

It is important to standardize FPC to the population being studied. This requires analysis of own measurements or previous publications in the specific region of interest. Meanwhile, the original FPC can shed some light on which patients may have a prolonged recovery.

Conclusions and Implications

First, we have presented evidence that the multi-item frailty screening tools, the FRAIL questionnaire and FPC, predicted a worse outcome after cardiac surgery, characterized by prolonged hospitalization, when ≥3 points were obtained, classified as frail.

Second, we also demonstrated that milder degrees (1-2 points), or pre-frailty, can also predict poor surgical outcomes, but only when the obtained points came from specific items, such as gait speed, grip strength, illness, and resistance. This again suggests that a single parameter screening may be a viable approach in cardiovascular disease patients.

Additionally, we independently analysed the scales’ individual items against confounding factors to determine which items offered pure information about the risk without being influenced by other known factors that may be present in frailty and in patients with cardiovascular disease. This is of extreme importance, as other authors have concluded [20], further study is needed to determine which components of frailty are most predictive of negative operative outcomes before integration in risk predicting scores.

In summary, primary frailty and secondary cardiovascular frailty overlap and interact. For this reason, we have tailored a more specific scale for cardiac surgery patients. The FCS is composed of items from well-known tools that were independent from other influences in our sample, and indicators of chronic cardiovascular or secondary frailty, such as PHT. We retrospectively developed the scale, using preoperative variables, to predict a higher preoperative risk of a poor outcome after intervention.

We can conclude that it is crucial to adjust frailty screening tools according to the specific characteristics of cardiovascular disease patients. Further research should be performed to validate this scale in a prospective cohort. More investigation into frailty in this exceptional population is important for the future.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of our institution on 16 October 2017, approval number: PI9510/2017. A total of 232 consecutive patients were enrolled from October 2017-December 2019. Of all eligible patients, only one refused to participate in the study. All patients signed an informed consent form and received an information sheet. The study follows the most recent STROBE [23] checklist.

Competing interests

No declared.

Authors' contributions

Conception or design of the work: Myriel M. López Tatis, Carlos Amorós Rivera, José María González Santos.

Data collection: Myriel M. López Tatis, Carlos Amorós Rivera, Francisco Javier López Rodríguez, María Elena Arnaiz García, Ramón Adolfo Arévalo-Abascal, Ana María Barral Varela, María Teresa Merino Vicente, José María González Santos.

Data analysis and interpretation: Myriel M. López Tatis, Carlos Amorós Rivera, José María González Santos.

Drafting the article: Myriel M. López Tatis, Carlos Amorós Rivera, José María González Santos.

Critical revision of the article: Myriel M. López Tatis, Carlos Amorós Rivera, José María González Santos.

Final approval of the version to be published: Myriel M. López Tatis, Carlos Amorós Rivera, Francisco Javier López Rodríguez, María Elena Arnaiz García, Ramón Adolfo Arévalo-Abascal, Ana María Barral Varela, María Teresa Merino Vicente, José María González Santos.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared

Funding statement

This work was supported by Gerencia Regional de salud de Castilla y León (grant: GRS 1844/A/18).

Availability of data and materials

Data bases in SPSS and Excel formats are available at the department of cardiovascular surgery, Hospital Universitario de Salamanca. Salamanca, Spain.

References

- Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in Relation to the Accumulation of Deficits. Can Med Assoc J 173 (2005): 489-495.

- Abellán García, A, Pujol Rodríguez, R. Un perfil de las personas mayores en España. Indicadores estadísticos básicos 11 (2016): 2-22.

- Afilalo J, Alexander KP, Mack MJ, et al. Frailty assessment in the cardiovascular care of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 63 (2014): 747-62.

- Lee DH, Buth KJ, Martin BJ, et al. Frail patients are at increased risk for mortality and prolonged institutional care after cardiac surgery. Circulation 121 (2010): 973-978.

- Sündermann S, Dademasch A, Rastan A, et al. One-year follow-up of patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery assessed with the Comprehensive Assessment of Frailty test and its simplified form. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 13 (2011): 119-123.

- Sündermann S, Dademasch A, Praetorius J, et al. Comprehensive assessment of frailty for elderly high-risk patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 39 (2011): 33-37.

- Di Dedda U, Pelissero G, Agnelli B, et al. Accuracy, calibration, and clinical performance of the new EuroSCORE II risk stratification system. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 43 (2013): 27-32.

- Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. 16 (2012): 601-608.

- Malmstrom TK, Miller DK, Morley JE. A comparison of four frailty models. J Am Geriatr Soc. 62 (2014): 721-726.

- Abizanda P, Romero L, Sánchez-Jurado PM, et al. Association between Functional Assessment Instruments and Frailty in Older Adults: The FRADEA Study. J Frailty Aging 1 (2012): 162-168.

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 56 (2001): 146-156.

- Alonso BC, Carnicero JA, Turín JG, et al. The Standardization of Frailty Phenotype Criteria Improves Its Predictive Ability: The Toledo Study for Healthy Aging. J Am Med Dir Assoc 18 (2017): 402-408.

- Boreskie KF, Kehler DS, Costa EC, et al. Standardization of the Fried frailty phenotype improves cardiovascular disease risk discrimination. Exp Gerontol. 119 (2019): 40-44.

- Afilalo J. Frailty in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease: Why, When, and How to Measure. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 5 (2011): 467-472.

- Wong TY, Massa MS, O'Halloran AM, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and frailty in a cross-sectional study of older people: implications for prevention. Age Ageing 47 (2018): 714-720.

- Shinmura K. Cardiac Senescence Heart Failure, and Frailty: A Triangle in Elderly People. Keio J Med 65 (2016): 25-32.

- Stewart R Cardiovascular Disease and Frailty: What Are the Mechanistic Links? Clin Chem 65 (2019): 80-86.

- Bäck C, Hornum M, Olsen PS, et al. 30-day mortality in frail patients undergoing cardiac surgery: the results of the frailty in cardiac surgery (FICS) Copenhagen study. Scand Cardiovasc J 53 (2019): 348-354.

- Bergquist CS, Jackson EA, Thompson MP, et al. Understanding the Association Between Frailty and Cardiac Surgical Outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 106 (2018): 1326-1332.

- Sepehri A, Beggs T, Hassan A, et al.. The impact of frailty on outcomes after cardiac surgery: a systematic review. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 148 (2014): 3110-3117.

- Buta BJ, Walston JD, Godino JG, et al. Frailty assessment instruments: Systematic characterization of the uses and contexts of highly-cited instruments. Ageing Res Rev 26 (2016): 53-61.

- Kim DH, Kim CA, Placide S, et al. Preoperative Frailty Assessment and Outcomes at 6 Months or Later in Older Adults Undergoing Cardiac Surgical Procedures: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med 165 (2016): 650-660.

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 147 (2007): 573-577.