Evaluation of Efficacy, Time Required For Pain Relief, and Adverse Effects of Ketorolac Tromethamine Injection (Im or Iv) in Inpatient Departments of Tertiary Level Hospitals in Bangladesh

Article Information

Prof. Dr. A.T.M Khalilur Rahman1, Prof. Dr. Md. Shamsul Alam2, Prof. Dr. Md. Nazmul Kayes3, Dr. Tasnim Mahmud4*, Md. Mamunur Rashid5

1Professor& Head, Department of Cardiac Anesthesia& Intensive Care Unit National Heart Foundation.

2Consultant, Department of Anesthesiology Bangladesh Specialized Hospital, Dhaka

3Department of Anesthesiology, Delta Medical College and Hospital, Mirpur, Dhaka

4Department of Public Health, North South University

5Department of Pharmacy, University of Dhaka

*Corresponding author: Dr. Tasnim Mahmud, Department of Public Health, North South University, Bangladesh

Received: 01 December 2025; Accepted: 08 December 2025; Published: 15 December 2025

Citation: Prof. Dr. A.T.M Khalilur Rahman, Prof. Dr. Md. Shamsul Alam, Prof. Dr. Md. Nazmul Kayes, Dr. Tasnim Mahmud, Md. Mamunur Rashid. Evaluation of Efficacy, Time Required For Pain Relief, and Adverse Effects of Ketorolac Tromethamine Injection (Im or Iv) in Inpatient Departments of Tertiary Level Hospitals in Bangladesh. Archives of Internal Medicine Research. 8 (2025): 346-351.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background:

Ketorolac is a chiral NSAID used for analgesia, available in tablets or injections. Its tromethamine component enhances solubility and absorption. Adverse effects are dose-dependent and can include nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Despite its adverse effects, ketorolac is becoming popular as an adjunct or replacement for corticosteroid injections. Objectives of the study was to evaluate efficacy, time required for pain relief and adverse effects of Ketorolac Tromethamine injection in tertiary level hospitals in Bangladesh.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted among participants aged ≥18 years with pain and/or inflammation evaluated by doctors, requiring NSAIDs (Ketorolac Tromethamine-Toradolin). The participant was purposively selected from in-patient department of different tertiary level healthcare facilities. After proper explanation of the study and with written informed consent, participants were prescribed ketorolac tromethamine injection through IV and IM route. Data was collected through a pretested, semi-structured, interviewer-administered questionnaire.

Results:

In this study, mean patient age was 37.23 ± 14.55 and 35 of the patients were male (22.88%), while 118 were female (77.12%). Ketorolac tromethamine is used mostly as a pain killer after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (22.88%), followed by LUCS (20.26%). Most (61.44%) people didn't need any additional medication for pain relief. Before administration of ketorolac Tromethamine injection, 61.4% of patients complained of strong pain, while after administration only 2% complained about strong pain. Level of pain before and after administration of ketorolac Tromethamine had strong association (p <0.001). After administration of ketorolac tromethamine injection, 86.3%(n=132) needed 11–20 minutes to relieve pain, followed by 7.8%(n=12) who needed <10 minutes. After receiving a ketorolac Tromethamine injection, 92.8% of patients experienced no side effects.

Conclusion:

Ketorolac worked quickly and effectively for pain relief, with most patients (86.3%) feeling better within 11–20 minutes. Strong pain dropped from 61.4% to just 2% after the injection. Almost all patients (92.8%) had no side effects, showing it is both fast and safe for managing pain.

Keywords

<p>Ketorolac tromethamine; NSAID; Pain score; Adverse effect</p>

Article Details

INTRODUCTION

Ketorolac tromethamine is a chiral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that is commonly used for its potent analgesic properties. It is administered as a water-soluble tromethamine salt, making it suitable for both oral and parenteral formulations, including tablets and injectable preparations [1]. The inclusion of tromethamine in its formulation significantly enhances the drug's solubility, thereby facilitating faster and more efficient absorption upon administration [2]. Ketorolac primarily exerts its pharmacological effect by inhibiting the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme, which is responsible for the conversion of arachidonic acid into thromboxanes, prostacyclin, and prostaglandins. These prostaglandins, when released at the site of injury or inflammation, contribute to the sensitization of afferent nociceptive nerve endings, amplifying pain perception [3].

Evidence from previous research suggests that intramuscular (IM) administration of ketorolac demonstrates superior analgesic efficacy compared to its intravenous (IV) counterpart, particularly when used intraoperatively. Importantly, this enhanced efficacy does not appear to be associated with a significant increase in adverse effects when administered via either route [3]. Given the well-documented side effect profile of opioids, which includes respiratory depression, sedation, constipation, psychomotor disturbances, tolerance, and physical dependence NSAIDs like ketorolac have emerged as a favorable alternative for acute pain management [3].

In recent clinical practice, ketorolac tromethamine has gained attention not only as an effective analgesic agent but also as a potential substitute for corticosteroid injections in selected cases [4]. NSAIDs, due to their dual analgesic and anti-inflammatory actions, have become first-line pharmacological agents in the treatment of moderate to severe pain conditions [5]. Nonetheless, the adverse effects of ketorolac remain a clinical concern, particularly as they tend to be dose-dependent. Common adverse reactions include gastrointestinal disturbances such as nausea, vomiting, and dyspepsia, as well as more severe complications like inhibition of platelet aggregation, gastrointestinal bleeding, allergic reactions, dizziness, and drowsiness [6].

Tertiary care hospitals in developing countries often manage a diverse array of clinical cases involving variable pain intensities. In such high-demand environments, effective and timely pain control is essential for enhancing patient satisfaction, reducing morbidity, and facilitating earlier mobilization and discharge. Ketorolac tromethamine offers a promising solution due to its rapid onset and strong analgesic profile. However, given its risk for adverse effects, continuous monitoring and proper evaluation are imperative. Notably, there is limited published evidence concerning the efficacy, onset time, and safety profile of ketorolac tromethamine in the specific healthcare context of Bangladesh. Therefore, the present study was designed to assess the clinical effectiveness, time to achieve pain relief, and adverse reactions associated with ketorolac tromethamine injection in both outpatient and inpatient departments of tertiary-level hospitals in Bangladesh.

Methods

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted over a three-month period, from October to December 2023, involving adult participants (aged ≥18 years) who presented with clinical signs of pain and/or inflammation and were evaluated by registered physicians as requiring nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), specifically ketorolac tromethamine (Toradolin). A total of 153 participants were recruited using purposive sampling techniques from both inpatient and outpatient departments of various tertiary-level healthcare institutions. The recruitment process was facilitated through direct collaboration with attending medical doctors, who assisted in identifying eligible patients based on inclusion criteria. Prior to enrollment, all participants received a comprehensive explanation of the study objectives, procedures, and potential risks and benefits. Written informed consent was obtained from each individual to ensure ethical compliance and voluntary participation. Following consent, participants were administered ketorolac tromethamine injections, either intravenously (IV) or intramuscularly (IM), based on the clinical judgment of the attending physician and the patient's condition.

Data were collected using a pre-tested, semi-structured questionnaire administered through face-to-face interviews. The questionnaire gathered information on socio-demographic profiles, clinical history, nature and severity of pain, duration of symptoms, and any reported adverse drug reactions following ketorolac administration. Pain intensity was assessed both prior to and following the injection using a validated pain score, allowing for quantifiable measurement of analgesic effectiveness. This approach facilitated a standardized comparison of pain relief outcomes and the onset of therapeutic effects across different routes of administration. The study protocol adhered strictly to ethical guidelines and ensured confidentiality and data protection throughout the research process.

|

Pain score |

Interpretation |

|

0 |

No pain |

|

1 |

Pain is very mild, barely noticeable. Most of the time you don't think about it |

|

2 |

Minor pain. It's annoying. You may have sharp pain now and then |

|

3 |

Noticeable pain. It may distract you, but you can get used to it |

|

4 |

Moderate pain. If you are involved in an activity, you're able to ignore the pain for a while. But it is still distracting |

|

5 |

Moderately strong pain. You can't ignore it for more than a few minutes. But, with effort, you can still work or do some social activities |

|

6 |

Moderately stronger pain. You avoid some of your normal daily activities. You have trouble concentrating |

|

7 |

Strong pain. It keeps you from doing normal activities |

|

8 |

Very strong pain. It's hard to do anything at all |

|

9 |

Pain that is very hard to tolerate. You can't carry on a conversation |

|

10 |

Worst pain possible |

After data collection, responses were checked, cleaned, edited, compiled, and coded to ensure accuracy, consistency, and relevance with the study objectives. The cleaned data were then entered into a pre-designed database using SPSS for Windows (IBM Corporation, New York). Outliers and missing values were identified and corrected. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 27. Descriptive statistics were presented as frequencies, percentages, means, standard deviations, and ranges. Fisher’s exact test was applied where appropriate, with a p-value <0.05 considered statistically significant.

The study received ethical clearance from the relevant Ethical Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after providing detailed information about the study’s purpose, procedures, risks, benefits, voluntary participation, and confidentiality measures. Anonymity was ensured by assigning unique identification numbers and coding all data. Access to information was restricted to authorized research personnel, and all collected data were used solely for research purposes.

Results

The socio-demographic analysis revealed that the majority of patients (55.48%) were aged between 21 and 40 years, with a mean age of 37.23 ± 14.55[Table 1], indicating that ketorolac is predominantly used in younger adults, likely due to their higher surgical rates or acute pain conditions. Its lower usage in older patients may reflect clinical caution given the risk of NSAID-related adverse effects. This age pattern mirrors global trends in postoperative pain management. Gender distribution showed a notable predominance of female patients (77.12%) [Table 2], possibly due to procedures like LUCS or other gynecological surgeries. This finding highlights the importance of gender-sensitive approaches in analgesic planning and invites further investigation into possible sex-based pharmacological or pain perception differences that may influence NSAID selection.

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the study population (n=153).

|

Age Group |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

Mean±SD |

|

<20 years |

16 |

10.32% |

|

|

21–30 years |

39 |

25.16% |

|

|

31–40 years |

47 |

30.32% |

|

|

41–50 years |

19 |

12.26% |

|

|

51–60 years |

16 |

10.32% |

|

|

>60 years |

16 |

10.32% |

37.23 ± 14.55 |

|

Total |

153 |

100% |

Table 2: Gender distribution of the study population.

|

Gender |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Female |

118 |

77.12 |

|

Male |

35 |

22.88 |

|

Total |

153 |

100 |

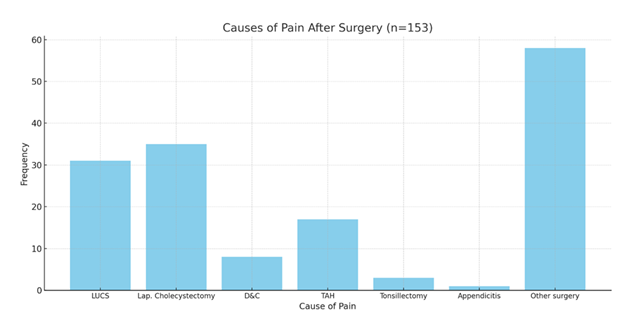

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (22.88%) and LUCS (20.26%) were the leading causes for ketorolac administration. This underlines its widespread use in managing moderate-to-severe postoperative pain in common abdominal and obstetric surgeries. These procedures typically involve short hospital stays, where fast-acting analgesics like ketorolac are advantageous. Its use across a spectrum of surgeries supports its broad clinical versatility. [Figure 1].

Ketorolac monotherapy was effective for 61.44% of patients. The remaining patients required adjuncts like paracetamol (24.84%) or opioids (10.46%), indicating that while highly effective, ketorolac may need supplementation in certain clinical scenarios. This could be due to individual variability in pain tolerance or the type/severity of surgery. The relatively low reliance on opioids also suggests ketorolac's role in minimizing opioid use, an important consideration in multimodal pain strategies [Table 3].

Table 3: Additional Medication for pain relief (n=153).

|

Medication |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

|

Paracetamol |

38 |

24.84% |

|

Pethidine hydrochloride |

16 |

10.46% |

|

Diclofenac Sodium |

5 |

3.27% |

|

No additional drug |

94 |

61.44% |

|

Total |

153 |

100.00% |

Table 4 shows that Intravenous (IV) administration overwhelmingly dominated (94.77%) compared to intramuscular (IM) (5.23%). This preference likely reflects the clinical need for rapid onset in acute or inpatient settings.

Table 4: Route of administration (n=153).

|

Route |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

|

I/V (Intravenous) |

145 |

94.77% |

|

I/M (Intramuscular) |

8 |

5.23% |

Pre-treatment, 61.4% had strong pain, which plummeted to just 2% post-injection—signifying ketorolac’s strong analgesic effect. The significant p-value (<0.001) statistically validates this improvement, confirming its therapeutic efficacy. Notably, moderate pain rose from 24.8% to 56.2% as shown in Table 5, indicating that while pain was not completely eliminated for some, it was significantly reduced. This marked reduction reinforces the importance of early NSAID intervention in postoperative pain management.

Table 5: Level of pain before and after administration of ketorolac (n=153).

|

Pain Score (VAS) |

Frequency (%) |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean±SD |

Significance |

|||

|

Before administration |

0-3: No/ Mild pain |

21 |

1 |

10 |

6.67 ±2.53 |

Fisher’s exact test |

||

|

4-6: Moderate pain |

38 |

|||||||

|

7-10: Strong pain |

94 |

|||||||

|

Afteradministration |

0-3: No/ Mild pain |

64 |

0 |

7 |

3.60 ±1.85 |

|||

|

4-6: Moderate pain |

86 |

|||||||

|

7-10: Strong pain |

3 |

|||||||

Table 6 presents the distribution of time required for pain relief following ketorolac injection among 153 patients. The results indicate that the majority of patients (86.3%) experienced pain relief within 11 to 20 minutes, suggesting a rapid onset of action for ketorolac in most cases. A small proportion of patients (7.8%) reported relief in less than 11 minutes, while 5.2% experienced relief between 21 to 30 minutes. Only one patient (0.7%) required more than 30 minutes for noticeable pain reduction.

Table 6: After administration of ketorolac injection, time required for pain relief (n=153).

|

Time Interval |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

|

<10 min |

12 |

7.80% |

|

11–20 min |

132 |

86.30% |

|

21–30 min |

8 |

5.20% |

|

>30 min |

1 |

0.70% |

The adverse effect profile was minimal, 92.8% reported no side effects. Mild symptoms like nausea (5.2%), itching (1.3%), and stomach pain (0.7%) were rare, reinforcing ketorolac’s favorable safety in clinical use [Table 7].

Table 7: Adverse effect of ketorolac (n=153).

|

Adverse Effects |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

|

No adverse effect |

142 |

92.80% |

|

Itching |

2 |

1.30% |

|

Stomach pain |

1 |

0.70% |

|

Nausea |

8 |

5.20% |

|

Total |

153 |

100.00% |

Discussion

This study investigated the efficacy and safety of ketorolac in pain management among 153 patients. The demographic profile revealed a predominance of younger persons, with a large female majority. Another study indicated that the mean patient age was 28.61±5.87 (range, 21-44), and 73 patients were male (47.09%), while 82 were female (52.90%) [7]. In this study, ketorolac tromethamine was used to treat post-operative pain from lower uterine cesarean section (LUCS), laparoscopic cholecystectomy, dilation and curettage (D&C), total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH), and tonsillectomy. The study's findings emphasize ketorolac's versatility in postoperative pain treatment across a wide range of surgeries. It could be also used for appendicitis. Another research investigation also documented ketorolac as being used to successfully treat musculoskeletal pain, migraines, and sickle cell crises, even pain linked with cancer that has metastasized to the bones [8]. So, ketorolac tromethamine was effective in all kind of pain. Our findings indicate that ketorolac was administered predominantly via the intravenous route due to its ease of administration and better control over pain alleviation. Another study confirmed that IV administration of ketorolac conferred no advantages over the IM route with regard to efficacy or speed of onset [9]. The effects of ketorolac were not affected by the route of administration. The study's findings suggest that most patients were able to get enough pain relief from ketorolac tromethamine on its own without the need for additional drugs. This discovery sheds light on the usefulness and effectiveness of ketorolac in the treatment of pain for a number of reasons, making it noteworthy. Having a single medicine that works well for managing pain helps streamline treatment plans, lower the chance of polypharmacy, and lessen the possibility of drug interactions.

Before administration of ketorolac, most patients reported strong pain, but after ketorolac administration, very few patients complained about strong pain. This dramatic reduction in pain levels can be attributed to ketorolac’s potent analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties. The significant improvement in pain levels post-administration highlights ketorolac’s efficacy as an analgesic for managing moderate to severe pain, particularly in the post-operative setting. This finding is consistent with earlier research indicating that ketorolac is beneficial in a variety of pain disorders, including post-surgical pain, musculoskeletal pain, and cancer-related pain. The findings of this study imply that ketorolac is an effective treatment for acute pain, but therapeutic judgments should always include a thorough assessment of the patient's general health and risks.

The findings of this trial show significant differences in the time required for patients to acquire complete pain relief with ketorolac tromethamine. Total 86.3% of the patients required 11-20 minutes to achieve complete pain relief, whereas 7.8% experienced complete relief within 10 minutes. A study documented that Intranasal ketorolac demonstrated good tolerability and delivered effective pain relief within 20 minutes, while also decreasing the need for opioid analgesics [10]. This heterogeneity could be influenced by the degree and type of the pain, individual differences in metabolism and reaction to medicine, and the presence of any underlying disorders that may alter drug efficacy.

According to the study's findings, most patients accepted ketorolac tromethamine well and most did not experience any serious adverse effects after taking it. This is a noteworthy result because it implies that ketorolac can be a safe and useful analgesic in a variety of therapeutic settings. But it's also critical to address the small percentage of individuals who did report experiencing uncomfortable side effects, such nausea, itching, and stomach pain. While one study found no adverse effects after administering ketorolac [10], another reported gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation, platelet inhibition with altered hemostasis, and renal impairment as among the list of adverse effects associated with the medication [11].

Conclusion

Ketorolac Tromethamine proved to be highly effective for postoperative pain relief, with majority of patients experiencing pain relief within 11–20 minutes. Notably, strong pain complaints dropped from 61.4% before administration to just 2% after treatment. Furthermore, 92.8% of patients reported no adverse effects, confirming its strong safety profile. These findings support ketorolac’s rapid action, safety, and clinical value in acute pain management.

Conflict of interest:

There is no conflict of interest.

Source of funding:

Self-funding

References

- Brocks DR, Jamali F. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Ketorolac Tromethamine. Clin Pharmacokinet [Internet]. Springer 23 (1992): 415-427.

- McAleer SD, Majid O, Venables E, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of ketorolac following single intranasal and intramuscular administration in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol [Internet]. J Clin Pharmacol 47 (2007): 13-18.

- Vadivelu N, Gowda AM, Urman RD, et al. Ketorolac tromethamine - Routes and clinical implications. Pain Pract. Blackwell Publishing Inc. 15 (2015): 175-193.

- Suwannaphisit S, Suwanno P, Fongsri W, et al. Comparison of the effect of ketorolac versus triamcinolone acetonide injections for the treatment of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. BioMed Central Ltd 23 (2022): 1-7.

- Macario A, Lipman AG. Ketorolac in the era of cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: A systematic review of efficacy, side effects, and regulatory issues. Pain Med. Oxford Academic 2 (2001): 336-351.

- Eidinejad L, Bahreini M, Ahmadi A, et al. Comparison of intravenous ketorolac at three doses for treating renal colic in the emergency department: A noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd 28 (2021): 768-775.

- Ucar F, Kadioglu E. Effectiveness of ketorolac-soaked bandage contact lens for pain management after photorefractive keratectomy. Cutaneous and Ocular Toxicology 42 (2023): 55-60.

- Mahmoodi AN, Patel P, Kim PY. Ketorolac. InStatPearls 2024 Feb 28. StatPearls Publishing.

- Parke TJ, Millett S, Old S, et al. Ketorolac for early postoperative analgesia. Journal of clinical anesthesia 7 (1995): 465-469.

- Singla N, Singla S, Minkowitz HS, et al. Intranasal ketorolac for acute postoperative pain. Curr Med Res Opin 26 (2010): 1915-1923.

- Reinhart DJ. Minimising the adverse effects of ketorolac. Drug safety 22 (2000): 487-497.