Effects of Ethanol and Caffeine Consumption on Neurogenesis, Cell Proliferation, and Apoptosis in the Dentate Gyrus of the Hippocampus of Voluntary Ethanol-Drinking Rats

Article Information

Martinez M 1#, Takase L. F1#, Baltazar D. R1, Martinez F. E 2*

1 Department of Morphology and Pathology, Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), São Carlos, SP, Brazil.

2 Department of Structural and Functional Biology, State University of São Paulo (UNESP), Botucatu, SP, Brazil.

# These authors contributed equally to this work

*Corresponding Author: Francisco Eduardo Martinez, Ph. D, Department of Structural and Functional Biology, Institute of Biosciences of Botucatu (IBB), UNESP - Univ Estadual Paulista, P.O

Received: 26 November 2025; Accepted: 27 November 2025; Published: 17 December 2025

Citation:

M. Martinez, L. F. Takase, D. R. Baltazar, F. E. Martinez. Effects of Ethanol and Caffeine Consumption on Neurogenesis, Cell Proliferation, and Apoptosis in the Dentate Gyrus of the Hippocampus of Voluntary Ethanol-Drinking Rats. Archives of Veterinary Science and Medicine. 8 (2025): 72-84.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

The combination of ethanol and caffeine, through the consumption of “energy” drinks, is becoming increasingly popular, especially among young people, as it is believed that caffeine can antagonize or at least decrease the intensity of the cognitive and motor deficits caused by ethanol intoxication. However, studies have shown that the combination of ethanol + caffeine only decreases the subjective perception of ethanol intoxication without, however, decreasing its intensity. This change in the subjective perception of ethanol intoxication can lead to an increase in the consumption of alcoholic beverages, potentiating the effects of ethanol on the central nervous system. In addition to the known neurodegenerative effects of ethanol, its excessive consumption also has an important suppressive effect on neurogenesis. The dentate gyrus of the hippocampus is one of the only structures where there is neurogenesis, the formation of new neurons, throughout adult life. As the hippocampus is involved in important processes such as learning, memory, and mood regulation, studies suggest that the decrease in neurogenesis in this structure may be directly related to the cognitive and behavioral problems presented in patients with alcoholism. The present study analyzed the effects of the simultaneous use of ethanol and caffeine on cell proliferation, neurogenesis, and apoptosis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus of UChB rats. Chronic ethanol ingestion triggered significant changes in the hippocampus of the UChB rats with decreased cell proliferation and neurogenesis, a more significant number of apoptotic cells, and reduced volume of the hippocampus. The simultaneous ingestion of ethanol and caffeine partially reversed the damage of ethanol, acting caffeine with a possible neuroprotective effect.

Keywords

Ethanol; Caffeine; Neurogenesis; Apoptosis; UChB rats

Article Details

1. Introduction

Alcoholism is a multifactorial syndrome compromising the individual's physical, mental, and social aspects [1]. Ethanol is the most consumed drug in the world, with widespread dissemination in all social classes and age groups. The increase in its consumption among young people and adolescents is alarming [2,3]. Understanding the potential effects of ethanol consumption, whether beneficial or harmful, is extremely important in preventing the damage associated with its use. The moderate consumption of alcoholic beverages is often considered a protective factor against cardiovascular diseases and the possible decrease in cognitive losses due to age [4,5] in addition to promoting stress reduction and anxiety, contributing to well-being [6]. However, the use of ethanol can also bring harm to health as an increase in the risk of developing some types of cancer [7] and cardiac diseases [8]. The combination of alcoholic drinks with juices or soft drinks masks the taste of ethanol, making the drink more palatable. The consumption of “energy drinks” containing varying amounts of caffeine and taurine combined with alcoholic drinks has become very popular with adolescents and young adults [9,10]. Since alcohol is a central nervous system (CNS) depressant while caffeine is a stimulant, many believe that caffeine can antagonize or at least decrease the intensity of cognitive and motor deficits caused by alcohol intoxication. Also, the primary motivations for combining energy drinks with alcohol are to mask their flavor, raise arousal levels, and quicken drunkenness [11]. Increased consumption of energy drinks may negatively influence neurodevelopment during childhood and adolescence, reducing immature oligodendrocyte survival and their differentiation capacity, which is accompanied by direct effects on neuronal integrity [12]. The consumption of energy drinks is also increasing among pregnant women with unaware of the potential effects on unborn offspring and even into puberty [13]. According to Speroni et al [14] consuming alcohol mixed with energy drinks (AmED) is a significant risk factor for both victimization and perpetration of violent acts. Given the same consumption frequency in the past year, AmED consumers typically reported higher associations with risk-taking behaviors compared to exclusive alcohol drinkers [15]. The subventricular zone and dentate gyrus of the hippocampus are the only brain structures where there is a proliferation of new neurons during adult life in several species, including man [16,17]. Neurogenesis is a complex process divided into cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Cell proliferation occurs through precursor cells present in the sub granular layer of the hippocampus or in the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricles. Some of these new cells degrade and die, while the survivors enter a process of differentiation into glial cells or neurons [18]. Most studies focus on neurons formed in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, as they may be involved in several cognitive and physiological processes [19,20]. However, the functional role of adult hippocampal neurogenesis is poorly understood.

Alcohol consumption is known to cause several brain anomalies. The pathophysiological changes associated with alcohol intoxication are mediated by various factors, the most notable being inflammation [21]. Ethanol consumption can affect neurogenesis in all phases (proliferation, survival, differentiation, and migration). The acute treatment showed a reduction in cell proliferation [22,23] and an increase in the number of apoptotic cells [24] in the dentate gyrus. The effects of chronic ethanol treatment are not yet fully understood and have conflicting results. While studies have shown a reduction in cell proliferation [25,26] others found no significant differences after 10 days [27] or 6 weeks [28] of exposure to ethanol, suggesting tolerance to its inhibitory effects. On the other hand, light alcohol consumption (LAC) may protect the brain against ischemic stroke by promoting neurogenesis [29]. The extent of affected adult neurogenesis by alcohol intoxication may depend on multiple factors like age, ethanol dose, and exposure pattern [26]. UChA (University of Chile Abstainer) and UChB (University of Chile bibulous) rat strains were developed through selective breeding for more than 70 generations and voluntarily drink 10% ethanol [30]. They are rare models for studies related to genetic, biochemical, physiological, nutritional, and pharmacological factors of the effects of alcohol, as well as appetite and tolerance, which are important characteristics of human alcoholism. The strain chosen is close to the reality of chronic human dependence on ethanol since animals consume ethanol voluntarily.

Objective

The study aimed to analyze the effects of simultaneous consumption of ethanol and caffeine on cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus of the UChB rat strain.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Animals

28 adults male UChB rats from the vivarium of the Department of Structural and Functional Biology of IBB / UNESP / Botucatu / SP and 14 Wistar rats from the vivarium of the Federal University of São Carlos / SP were used. The animals were kept in polyethylene boxes measuring 40x30x15cm, with solid bottoms, lined with shavings substrate, under controlled conditions of light (12h of light and 12h of dark) and temperature (from 200 to 25 0C), being provided filtered water and chow (Nuvital) ad libitum. The experimental protocol followed the ethical principles in animal research adopted by the Brazilian College of Animal Experimentation (COBEA).

2.2. UChB standardization

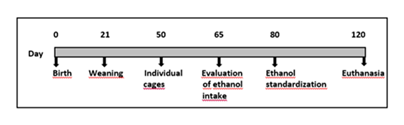

The UChB strain was chosen for consuming ethanol voluntarily and Figure 1 outlines the selection of animals used. The day of birth of the litter was stipulated as day zero. Weaning was performed at 21 days of age, where male puppies were housed in boxes with a minimum of two and a maximum of four animals, avoiding stress due to social isolation. The animals were transferred to individual cages at 50 days. At 65 days of age, the animals received, in addition to water, another bottle containing 10 % ethanol solution, and both bottles were alternated in the cage weekly. After 15 days of evaluation of the ingestion of 10 % ethanol solution, the selection and standardization of the UChB strain occurred. The rats that presented an average consumption greater than 7.0 g / kg per day of ethanol were selected for the UChB strain.

2.3. Experimental procedures

The animals were divided into three experimental groups with 14 rats per group. The groups UChB + caffeine (10% ethanol solution plus 300 mg / l caffeine) and UChB (10% ethanol solution) were formed by UChB strain rats. The control group was formed by Wistar rats maintained under normal conditions, without receiving ethanol or caffeine. Throughout the 40-day consecutive experimental period, the rats of the UChB group had access to a bottle containing water and another of 10% ethanol solution, and the UChB + caffeine group to a water bottle and another bottle with 10% ethanol plus caffeine (300 mg / l) (Figure 1). As in the selection period, the bottles were alternated weekly. During this period, the animals were weighed, and the consumption of the solutions was measured every 7 days. Collection procedures of all animals’ groups were carried out in the morning and on the same day.

2.4. Processing of biological material

BrdU (Sigma Aldrich Chemical Co.) was dissolved in sterile saline (containing 0.007 N NaOH) at a concentration of 20 mg/ ml, 30 minutes before administration. Eight animals from each group received a single intraperitoneal injection of BrdU (200 mg/kg) and were perfused 28 days later, a period necessary for the newly formed cells to go through the process of cell survival and differentiation. For the infusion, the animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (20 mg/kg) and transcardiac infused with 0.9% saline solution, followed by paraformaldehyde 4 % in sodium phosphate buffer (PBS), 0.1M and pH 7, 4, at 40 ºC. The brains were removed, post-fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 ºC for 24 h, cryoprotected in a 30% sucrose solution in PBS, and cryosectioned in coronal sections of 40 micrometers thick, collected in 12 series. The cuts were stored in an antifreeze solution in the -20 ºC freezer.

2.5. Ki-67, BrdU and Nissl

Series 6 sections were processed with immunohistochemistry technique against Ki-67 for the study of cell proliferation, while series 7 was processed with immunohistochemistry against BrdU for the study of neurogenesis. Series 8 was stained with cresyl violet, Nissl technique for volumetric analysis of the dentate gyrus. To process the material with immunohistochemistry techniques against BrdU and Ki-67, initially, the cuts were mounted sequentially on special slides (Superfrost plus Gold, Fisher Scientific, USA) and dried in an oven at 370 ºC for 8 h. To unmask the antigen, the slides were boiled in citric acid (0.01 M, pH 6.0) for 6 minutes and cooled to room temperature for 20 minutes. After this period, the cuts were quickly dipped in distilled water and then washed in PBS. In this step, slides processed against Ki-67 were incubated in primary antibody against Ki-67 (made in mice, 1: 200, Novocastra Laboratories Ltd., Newcastle, United Kingdom) in PBS containing 0.5% Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) for 48 h at 4 ºC. The blades processed against BrdU went through the additional steps described below. The tissue was digested in trypsin solution (0.1% in 0.1 M tris buffer, pH 7.5, containing 0.1% CaCl2) for 8 minutes. After new washes in PBS, the cuts were denatured in an acid solution (2.4N HCl in PBS) for 30 minutes. After further washing, the sections were incubated in primary antibody against BrdU (made in mice, 1: 200, Novocastra Laboratories Ltd., Newcastle, United Kingdom) in PBS containing 0.5 % Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) for 48 h at 4 ºC. After this period, the cuts processed against Ki-67 and BrdU were again washed in PBS and incubated in the biotinylated secondary antibody (horse against mouse, 1: 200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) in PBS for 120 minutes at room temperature. After fresh washes in PBS, the cuts were incubated in the avidin-biotin complex (Vectastain Elite ABC kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 90 minutes at room temperature. After new washes in PBS, the cuts were reacted using 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as a chromogen. The reaction was stopped with new washes in PBS. The slides were counter-stained with cresyl violet and mounted with coverslips using DPX (BDH, Gallard-Schlesinger Industries Inc., Carle Place, NY, USA) as a mounting medium.

For the quantitative analysis of immunoreactive neurons to BrdU or Ki-67, only cells with well-established limits and evident marking were considered bilaterally in all cuts along the entire dentate hippocampus extension. The quantification results correspond to the average of the sum of neurons found in each of the multiple cuts of an animal. For statistical analysis, ANOVA was used and the Newman-Keul multiple comparison test with statistical value p < 0.05 considered significant. For the bilateral volumetric analysis of the dentate gyrus, the images were captured through a digital camera coupled to the microscope and analyzed by the program Image J 1.38b. The analyzed areas were added, multiplied by the thickness of the cut (40 μm) and the distance between the cuts to calculate the estimate of the total volume of the structure. The quantification results correspond to the average of the sum of the results found in each of the multiple cuts of an animal. For the statistical analysis, ANOVA was used and the Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test with a statistical value of p< 0.05 was considered significant.

2.6. Doublecortin (DCX)

A series of cuts were processed with immunohistochemistry techniques against doublecortin (DCX), a protein associated with microtubules and expressed in precursor cells and immature neurons. The reaction was carried out by the free-floating method. The cuts were initially washed in PBS and incubated in 0.6% H2O2 for 10 minutes to remove endogenous peroxidase. After fresh washes, the cuts were incubated in normal 2% goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 1 h to minimize the binding of antibodies at non-specific sites. Then, the sections were immediately incubated in primary anti-DCX antibody (Abcam, made in rabbit, 1: 1000) for 48 h. The cuts were washed and incubated in a biotylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA, made in goat against rabbit, 1: 200) for 90 minutes. After this period, the cuts were washed again and incubated in an avidin-biotin complex (ABC Kit Elite, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 90 minutes. After new washes, the sections were stained using DAB (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as a chromogen. The reaction was stopped with new washes and cuts mounted sequentially on slides and dried at room temperature for 8 h.

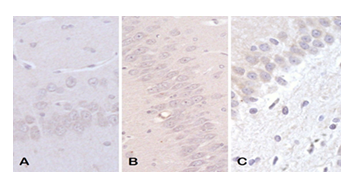

2.7. Caspase-3 and Xiap

Five rats from each group were anesthetized and perfused with paraformaldehyde fixative solution through the left ventricle of the heart. The brains were dissected and fixed in a paraformaldehyde solution. The embedded samples were cut to three μm thick in a Reichert Jung 2040 microtome and the prepared slides were first stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) for prior analysis. Immunohistochemical reactions were obtained using the monoclonal lyophilized Caspase-3 - (CPP32) antibodies - Novocastra and XIAP (X-linked Apoptosis Inhibitor Protein - SC - 11426 polyclonal - Santa Cruz. And the avidin-biotin-immunoperoxidase with antigenic recovery (Taylor et al., 1994), for the Caspase-3 and XIAP antibodies. Dilutions used for the Caspase-3 and XIAP antibodies were 1: 200. The tissue samples used as positive controls were human palatine tonsils. The slides were analyzed and photographed in a Zeiss Axiostar Plus photomicroscope from the Anatomy Laboratory of DMP / UFSCar.

3. Results

3.1. Cell proliferation - Ki 67 immunoreactive cells

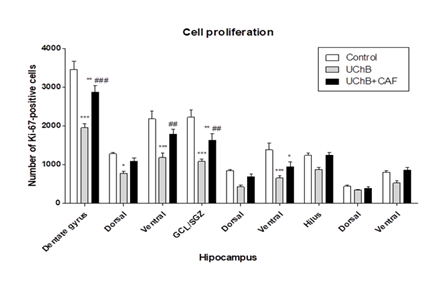

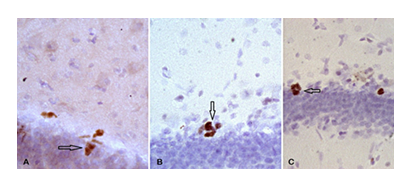

It showed a statistically significant difference between the study groups. The UChB group had a lower number of proliferation cells compared to the Control group. UChB + caffeine group was intermediate (Figure 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Effect of ethanol and caffeine consumption on cell proliferation in the hippocampus of UChB rats assessed by the number of Ki-67 positive cells in different hippocampal regions. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis: two-way Anova and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test.*p<0.05 vs control, ** p<0.01 vs control, *** p<0.001 vs control, ## p≤0.01 vs UChB, ### p≤0.001 vs UChB

3.2. Neurogenesis - BrdU immunoreactive cells

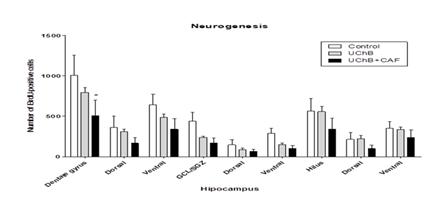

It showed a difference between the analyzed groups. The UChB + caffeine group had a lower number of immunoreactive cells compared to the Control and UChB groups (Figure 4 and 5).

Figure 4: Effect of ethanol and caffeine consumption on BrdU immunoreactive cells in the hippocampus of UChB rats assessed by the number of Ki-67 positive cells in different hippocampal regions. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis: two-way Anova and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. *p<0.05 vs control

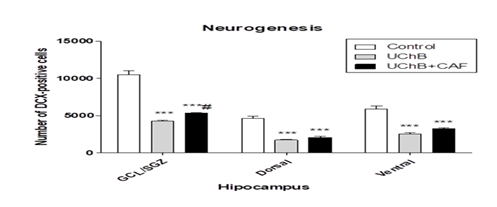

3.3. Neurogenesis - DCX immunoreactive cells

It showed a statistical difference between the studied groups. A smaller number of immunoreactive cells was observed in the UChB and UChB + caffeine groups compared to the Control group (Figs. 6 and 7).

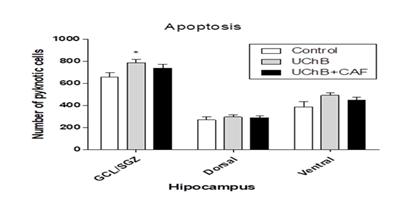

3.4. Apoptotic cells - Immunoreactive cells to cresyl violet

It showed a difference between analyzed groups. The UChB rats showed a higher number of pycnotic cells compared to the Control and UChB + caffeine group (Figs. 8 and 9).

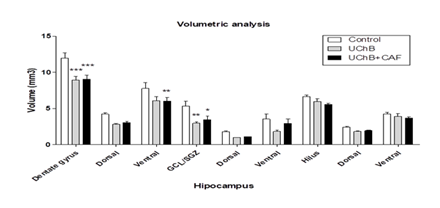

3.5. Volumetric analysis

It showed a statistical difference between analyzed groups. The UChB groups showed a lower total volume of the dentate hippocampal gyrus compared to Control group (Figure 10).

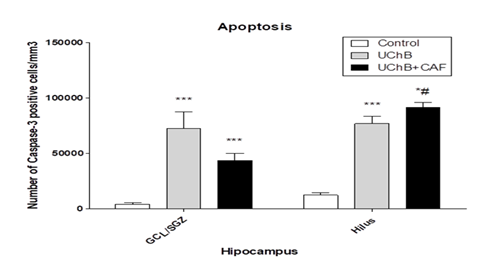

3.6. Apoptotic cells - Immunoreactive cells to Caspase 3

It showed a difference between studied groups. UChB groups exhibited a greater number of apoptotic cells compared to the Control group (Figure 11 and 12).

3.7. Immunoreactive cells to Xiap.

Neuronal cells in the hippocampus showed no reaction to Xiap (Figure 13).

4. Discussion

UChB rat strains have been adopted in different research related to alcoholism due to their characteristics of voluntary ethanol consumption [31]. This phenotype, selected from the Wistar lineage for decades, presents well-established consumption profiles and brings the experiment closer to the reality of chronic human alcoholism. The literature presents several experimental methodologies against chronic alcoholism, differing in terms of the species used, exposure time, ethanol concentration, types of diets, and groups [32,33,34]. Many of these methodologies are invasive, triggering stressful factors that increase glucocorticoid levels and stimulate the production of glutamate in the hippocampus. These responses can inhibit and alter hippocampal cell proliferation processes [35]. The present research showed that chronic ethanol intake triggered significant changes in the hippocampus of UChB animals with a decrease in cell proliferation and neurogenesis, a greater number of apoptotic cells, and a reduction in hippocampal volume. Ethanol consumption can potentially affect neurogenesis in all its stages. Acute treatment showed a 40 % reduction in cell proliferation [24,22] and a 134 % increase in the number of cells undergoing apoptosis [24] in the dentate gyrus of rats when compared with the control group. The effects of chronic treatment are not yet clear and show conflicting results in literature. While some studies demonstrated a reduction in cell proliferation after chronic treatment with ethanol, others found no significant differences after 10 days [27] or 6 weeks [28] of chronic exposure to alcohol, suggesting tolerance to its inhibitory effects. Moderate ethanol consumption decreased neurogenesis in the hippocampus of rats by 40 %, that is, even daily doses of ethanol considered low and socially accepted and legal had serious consequences for the structural integrity of the brain and mental health. The data presented reinforces the fine line between “harmless” drinking or “supposedly healthy” drinking associated with neuronal damage and dysfunction. Social and/or daily drinking may be more harmful to brain health than commonly recognized by the public [36]. Loss of hippocampal neurogenesis and loss of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons provide examples of how adolescent intermittent ethanol (AIE) ingestion-induced epigenetic and neuroimmune signaling provide novel therapeutic targets for adult alcohol use disorder [37]. The mechanisms underlying the persistent AIE-induced loss of adult hippocampal neurogenesis could contribute to broader neurodegeneration, loss of hippocampal neuroplasticity, and cognitive dysfunction [38,34] found less neurogenesis in the hippocampus of adolescent rats after intermittent inhalation of ethanol vapor for 35-36 days through analysis by Ki 67, BrdU and DCX. Caspase 3 immunoreactive cells were higher in these alcoholic animals. These results corroborate the behavioral data that alcoholic animals exhibited less anxious and disinhibited. Ethanol consumption results not only in behavioral changes but also in the plasticity of the nervous system. Regarding the decrease in hippocampal volume, our data are in agreement with those described in the literature. Through image analysis techniques in alcoholic individuals, a reduction in brain volume specifically in the hippocampus was observed [39] and in models of chronic alcoholism, adult mice treated with ethanol only on the 8th day of life showed decreased brain volume when compared to control animals [40]. The vitality of stem cells is essential for the growth of the developing brain. Growth factors can define the survival of neural stem cells and ethanol can affect the mediated activities of these growth factors. Ethanol alters the capacity of neuroblasts to become neurons in the adult neurogenic niche during neurodevelopment. These results suggest that pathways implicated in cell determination are affected by perinatal ethanol exposure and remain affected in adulthood [41]. Thus, ethanol induces brain stem cell death through two distinct molecular mechanisms, one is initiated by TGFβ1- FasL and the other (through TNF) which is independent of TGFβ1. Both ethanol and TGFβ1 cause upregulation of transcription of proteins involved in the extrinsic apoptotic pathway Hicks et al [42]. identified a specific set of p53-related genes in cells of the central nervous system that are altered by exposure to ethanol in both humans and animal models. Changes in the expression of these genes are important in understanding the mechanisms related to the toxic effects of alcohol on the central nervous system. Alcohol abuse triggers neuroinflammation, leading to neuronal damage and further memory and cognitive impairment [43]. Neuroinflammation, driven by different immune components such as activated glia, cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species, can regulate every step of adult neurogenesis, including cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, survival of newborn neurons, maturation, synaptogenesis, and neurogenesis [44]. The present study showed that the simultaneous ingestion of ethanol and caffeine partially reversed the damage caused by ethanol, with caffeine having a possible neuroprotective effect. Research involving hippocampal neurogenesis and caffeine reports conflicting results. Animals that received low doses of caffeine for a period of 7 days (10 mg/kg per day) did not show changes in cell proliferation rates in the hippocampus; animals that received moderate or high doses (20-30 mg/kg per day, respectively) showed suppression; and animals that received extreme doses of caffeine (60 mg/kg per day) had increased proliferation [45]. Acute administration of 60 mg/kg per day showed a reduction of approximately 44 % in cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus of rats [23,46] reported the effects of chronic consumption of low doses of caffeine on neurogenesis in the hippocampus of rats. The results showed fewer BrdU immunoreactive cells in the treated rats compared to those in the control group. Humans report feeling less intoxicated when caffeine and alcohol are co-administered [47] caffeine antagonizes alcohol impairment in a laboratory test of inhibitory control [48]. These data corroborate an interaction between the central nervous system, ethanol, and the adenosinergic system. With emphasis on intracellular mechanisms, adenosine receptors were shown to be regulated by caffeine. Activation of the adenosine A2a receptor is an antagonist of the dopamine D2 receptor that is related to increased neurogenesis [49]. The toxicity produced by caffeine in the hippocampus is probably mediated by the antagonism of A1 receptors and the subsequent decrease in inhibition of NMDA receptors. A similar conclusion for the importance of the A1 receptor is based on the relationship with the effects of caffeine on motor behavior. It is well-accepted that acute caffeine produces dose-dependent biphasic effects in terms of motor stimulation in rodents [50]. The modulation of cell proliferation by caffeine may be correlated to P53-dependent or -independent mechanisms [51]. Adenosine receptors have neuroprotective properties during periods of neuronal hyperexcitability and, therefore, have the potential to improve neuronal and behavioral excitability, contributing to less cognitive impairment. The increase in the simultaneous use of caffeine and alcohol and the importance of understanding the interaction of ethanol with the adenosine receptor system in this joint use of these substances is essential [52]. According to [53] caffeine can antagonize cognitive and psychomotor deficits induced by ethanol consumption. Chronic caffeine ingestion causes a marked and special effect on the neurochemical profile of the hippocampus, selectively affecting the level of osmolytes with an increase in taurine levels, leading to the hypothesis that the neuroprotection of caffeine may also be related to this ability to impact the osmotic adaptation of brain tissue. This effect of caffeine on taurine homeostasis in the hippocampus of diabetic rats may be related to the ability of adenosine receptors to control osmotic swelling and release taurine from both neurons and glial cells [54]. A precise understanding of the effects of simultaneous chronic ingestion of ethanol and caffeine still provides broad directions along the lines of research in this area.

5. Conclusions

Chronic ethanol consumption significantly altered cell proliferation and death mechanisms, decreasing hippocampal neurogenesis. The simultaneous ingestion of ethanol and caffeine partially reversed the damage caused by ethanol, with caffeine having a possible neuroprotective effect on the process of neurogenesis in the hippocampus of UChB rats.

6. Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, Grants # 2011/50366-6).

References

- Edwards G, Gross MM. Alcohol dependence: provisional description of a clinical syndrome. Br. Med. J 1 (1976): 1058-1061.

- Vieno A, Canale N, Potente R, et al. The multiplicative effect of combining alcohol with energy drinks on adolescent gambling. Addict Behav 82 (2018): 07-13.

- Towner TT, Varlinskaya EI. Adolescent Ethanol Exposure: Anxiety-Like Behavioral Alterations, Ethanol Intake, and Sensitivity. Front Behav Neurosci 14 (2020): 45.

- Farchi G, Fidanza F, Giampaoli S, et al. Alcohol and survival in the Italian rural cohorts of the Seven Countries Study.Int J Epidemiol 29 (2000): 667-67.

- Stampfer MJ, Kang JH, Chen J, et al. Effects of moderate alcohol consumption on cognitive function in women. N Engl J Med 352 (2005): 245-253.

- Neto MRL. Saúde Mental. São Paulo. Psicanál. Online, 2003. Alcohol alert, NIIAA National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 16 (2003): 315.

- Barron KA, Jeffries KA, Krupenko NI. Sphingolipids and the link between alcohol and cancer. Chem Biol Interact 322 (2020): 109058.

- Fernández-Solà J. The Effects of Ethanol on the Heart: Alcoholic Cardiomyopathy. Nutrients 12 (2020): 572.

- Tarragon E, Calleja-Conde J, Giné E, et al. Alcohol mixed with energy drinks: what about taurine? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 238 (2021): 01-08.

- Tarragon E. Alcohol and energy drinks: individual contribution of common ingredients on ethanol-induced behaviour. Front Behav Neurosci 17 (2023): 1057262.

- Verster JC, Benson S, Johnson SJ, et al. Alcohol mixed with energy drink (AMED): A critical review and meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharmacol 33 (2018): e2650.

- Serdar M, Mordelt A, Müser K, et al. Detrimental Impact of Energy Drink Compounds on Developing Oligodendrocytes and Neurons. Cells 8 (2019): 13-81.

- Alamneh AA, Endris BS, Gebreyesus SH. Caffeine, alcohol, khat, and tobacco use during pregnancy in Butajira, South Central Ethiopia. PLoS One 15 (2020): e0232712.

- Speroni J, Fanniff AM, Edgemon JM, et al. Alcohol mixed with energy drinks and aggressive behaviors in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 104 (2023): 102-319.

- Scalese M, Benedetti E, Cerrai S, et al. Alcohol versus combined alcohol and energy drinks consumption: Risk behaviors and consumption patterns among European students. Alcohol 110 (2023): 15-21

- Kempermann G, Wiskott L, Gage FH. Functional significance of adult neurogenesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol 14 (2004): 186-191.

- Anand SK, Mondal AC. Cellular and molecular attributes of neural stem cell niches in adult zebrafish brain. Dev Neurobiol 77 (2017): 1188-1205.

- Christie BR, Cameron HA. Neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Hippocampus 16 (2006): 199-207.

- Gross CG. Neurogenesis in the adult brain: death of a dogma. Nat Rev Neurosci 1 (2000): 67-73.

- Jacobs BL, Praag H, Gage FH. Adult brain neurogenesis and psychiatry: a novel theory of depression. Mol Psychiatry 5 (2000): 262-269.

- Anand SK, Ahmad MH, Sahu MR, Subba R, Mondal AC. Detrimental Effects of Alcohol-Induced Inflammation on Brain Health: From Neurogenesis to Neurodegeneration. Cell Mol Neurobiol 43 (2023): 1885-1904.

- Nixon K, Crews FT. Binge ethanol exposure decreases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J Neurochem 83 (2002): 1087-1093.

- Kochman LJ, Fornal CA, Jacobs BL. Suppression of hippocampal cell proliferation by short-term stimulant drug administration in adult rats. Eur J Neurosci 29 (2009): 2157-65.

- Jang MH, Shin MC, Jung SB, et al. Alcohol and nicotine reduce cell proliferation and enhance apoptosis in dentate gyrus. Neuroreport 13 (2002): 1509-1513.

- He J, Nixon K, Shetty AK, et al. Chronic alcohol exposure reduces hippocampal neurogenesis and dendritic growth of newborn neurons. Eur J Neurosci 21 (2005): 2711-2720.

- Nixon K. Alcohol and adult neurogenesis: roles in neurodegeneration and recovery in chronic alcoholism. Hippocampus 16 (2006): 287-295.

- Rice AC, Bullock MR, Shelton KL. Chronic ethanol consumption transiently reduces adult neural progenitor cell proliferation. Brain Res 1011 (2004): 94-98.

- Herrera DG, Yague AG, Johnsen-Soriano S, et al. Selective impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis by chronic alcoholism: protective effects of an antioxidant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 (2003): 7919-1924.

- Li J, Li C, Subedi P, et al. Light Alcohol Consumption Promotes Early Neurogenesis Following Ischemic Stroke in Adult C57BL/6J Mice. Biomedicines 11 (2023): 10-74

- Mardones J, Segovia-Riquelme N. Thirty-two years of selection of rats by ethanol preference: UChA and UChB strains. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol 5 (1983): 171-178.

- Quintanilla ME, Tampier L. Place conditioning with ethanol in rats bred for high (UChB) and low (UChA) voluntary alcohol drinking. Alcohol 45 (2011): 751-62.

- Popova E. N. Sensomotor córtex ultrastrucure in pubertal offspring of alcoholized male rats. Morfologiia 126 (2004): 8-11.

- Cardenas V, Studholme C, Gazdizinski S, et al. Deformation-based morphometry of brain changes in alcohol dependence and abstinence. NeuroImage 34 (2007): 879-887.

- Ehlers C L, W Liu, D N Wills, et al. Periadolescent ethanol vapor exposure persistently reduces measures of hippocampal neurogenesis that are associated with behavioral outcomes in adulthood, Neuroscience 244 (2013): 1-15.

- Gould E, Cameron HA, Daniels DC, et al. Adrenal hormones suppress cell division in the adult rat dentate gyrus. J Neurosci 12 (1992): 3642-6450.

- Anderson ML, Nokia MS, Govindaraju KP, et al. Moderate drinking? Alcohol consumption significantly decreases neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Neuroscience 224 (2012): 202-209.

- Crews FT, Coleman LG Jr, Macht VA, et al. Targeting Persistent Changes in Neuroimmune and Epigenetic Signaling in Adolescent Drinking to Treat Alcohol Use Disorder in Adulthood. Pharmacol Rev 75 (2023): 380-396.

- Macht V, Crews FT, Vetreno RP. Neuroimmune and epigenetic mechanisms underlying persistent loss of hippocampal neurogenesis following adolescent intermittent ethanol exposure. Curr Opin Pharmacol 50 (2020): 09-16.

- Sullivan EV, Marsh L. Hippocampal volume deficits in alcoholic Korsakoff's syndrome. Neurology 61 (2003): 1716-1719.

- Coleman LG Jr, Oguz I, Lee J, et al. Postnatal day 7 ethanol treatment causes persistent reductions in adult mouse brain volume and cortical neurons with sex specific effects on neurogenesis. Alcohol 46 (2012): 603-612.

- Villalba NM, Madarnas C, Bressano J, et al. Perinatal ethanol exposure affects cell populations in adult dorsal hippocampal neurogenic niche. Neurosci Res 198 (2024): 8-20.

- Hicks Steven D, Lewis Lambert, Ritchie Julie. Evaluation of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and dna-repair genes as potential biomarkers for ethanol-induced cns alterations. Neuroscience 13 (2012):128

- Wei H, Yu C, Zhang C, et al. Butyrate ameliorates chronic alcoholic central nervous damage by suppressing microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and modulating the microbiome-gut-brain axis. Biomed Pharmacother 160 (2023): 114-308

- Amanollahi M, Jameie M, Heidari A, et al. The Dialogue Between Neuroinflammation and Adult Neurogenesis: Mechanisms Involved and Alterations in Neurological Diseases. Mol Neurobiol 60 (2023): 923-959.

- Wentz CT, Magavi SS. Caffeine alters proliferation of neuronal precursors in the adult hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 56 (2009): 994-1000.

- Han, Myoung-Eun, Kyu-Hyun Park, et al. Inhibitory effects of caffeine on hippocampal neurogenesis and functioBiochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 356 (2007): 976-980.

- Ferreira SE, de Mello MT, Pompeia S et al. Effects of energy drink ingestion on alcohol intoxication. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30 (2006): 598-605.

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT. Dissociative antagonistic effects of caffeine on alcohol-induced impairment of behavioral control. Exp Clin Psychpharmacol 11 (2003): 228-36.

- Ohtani N, T Goto, C. Waeber, P.G. Bhide. Dopamine modulates cell cycle in the lateral ganglionic eminence, J. Neurosci 23 (2003): 2840-2850.

- Butler TR, Smith KJ, Berry JN, et al. Sex differences in caffeine neurotoxicity following chronic ethanol exposure and withdrawal. Alcohol Alcohol 44 (2009): 567-74.

- Hashimoto T, Z He, WY Ma, et al. Dong, Caffeine inhibits cell proliferation by G0/G1 phase arrest in JB6 cells, Cancer Res 64 (2004): 3344-3349.

- Tracy R. Butler and Mark A. Prendergast. Neuroadaptations in Adenosine Receptor Signaling Following Long-Term Ethanol Exposure and Withdrawal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36 (2012): 4-13.

- Hilbert ML, May CE, Griffin WC 3rd. Conditioned reinforcement and locomotor activating effects of caffeine and ethanol combinations in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 110 (2013): 168-173.

- Duarte JM, Carvalho RA, Cunha RA, et al. Caffeine consumption attenuates neurochemical modifications in the hippocampus of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Neurochem 111 (2009): 368-379.