Effectivity and Efficiency of repeat testing of Health care workers (HCW) for SARS-CoV-2

Article Information

Michael A Scherer*

Department for Trauma and Orthopedic Surgery, Helios Amperkliniken, Krankenhausstraße 15, 85221 Dachau, Germany

*Corresponding Author: Dr. Michael A. Scherer, Department for Trauma and Orthopedic Surgery, Helios Amperkliniken, Krankenhausstraße 15, 85221 Dachau, Germany

Received: 20 April 2021; Accepted: 27 April 2021; Published: 11 May 2021

Citation: Michael A Scherer. Effectivity and efficiency of repeat testing of health care workers (HCW) for SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Surgery and Research 4 (2021): 278-283.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookKeywords

Hospitals, Health care workers, COVID-19, PCR tests

Hospitals articles; Health care workers articles; COVID-19 articles; PCR tests articles

Hospitals articles Hospitals Research articles Hospitals review articles Hospitals PubMed articles Hospitals PubMed Central articles Hospitals 2023 articles Hospitals 2024 articles Hospitals Scopus articles Hospitals impact factor journals Hospitals Scopus journals Hospitals PubMed journals Hospitals medical journals Hospitals free journals Hospitals best journals Hospitals top journals Hospitals free medical journals Hospitals famous journals Hospitals Google Scholar indexed journals Health care workers articles Health care workers Research articles Health care workers review articles Health care workers PubMed articles Health care workers PubMed Central articles Health care workers 2023 articles Health care workers 2024 articles Health care workers Scopus articles Health care workers impact factor journals Health care workers Scopus journals Health care workers PubMed journals Health care workers medical journals Health care workers free journals Health care workers best journals Health care workers top journals Health care workers free medical journals Health care workers famous journals Health care workers Google Scholar indexed journals COVID-19 articles COVID-19 Research articles COVID-19 review articles COVID-19 PubMed articles COVID-19 PubMed Central articles COVID-19 2023 articles COVID-19 2024 articles COVID-19 Scopus articles COVID-19 impact factor journals COVID-19 Scopus journals COVID-19 PubMed journals COVID-19 medical journals COVID-19 free journals COVID-19 best journals COVID-19 top journals COVID-19 free medical journals COVID-19 famous journals COVID-19 Google Scholar indexed journals PCR tests articles PCR tests Research articles PCR tests review articles PCR tests PubMed articles PCR tests PubMed Central articles PCR tests 2023 articles PCR tests 2024 articles PCR tests Scopus articles PCR tests impact factor journals PCR tests Scopus journals PCR tests PubMed journals PCR tests medical journals PCR tests free journals PCR tests best journals PCR tests top journals PCR tests free medical journals PCR tests famous journals PCR tests Google Scholar indexed journals occupational disease articles occupational disease Research articles occupational disease review articles occupational disease PubMed articles occupational disease PubMed Central articles occupational disease 2023 articles occupational disease 2024 articles occupational disease Scopus articles occupational disease impact factor journals occupational disease Scopus journals occupational disease PubMed journals occupational disease medical journals occupational disease free journals occupational disease best journals occupational disease top journals occupational disease free medical journals occupational disease famous journals occupational disease Google Scholar indexed journals infection rate articles infection rate Research articles infection rate review articles infection rate PubMed articles infection rate PubMed Central articles infection rate 2023 articles infection rate 2024 articles infection rate Scopus articles infection rate impact factor journals infection rate Scopus journals infection rate PubMed journals infection rate medical journals infection rate free journals infection rate best journals infection rate top journals infection rate free medical journals infection rate famous journals infection rate Google Scholar indexed journals point of care articles point of care Research articles point of care review articles point of care PubMed articles point of care PubMed Central articles point of care 2023 articles point of care 2024 articles point of care Scopus articles point of care impact factor journals point of care Scopus journals point of care PubMed journals point of care medical journals point of care free journals point of care best journals point of care top journals point of care free medical journals point of care famous journals point of care Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

1. Introduction

On the 9th of January 2021 roughly 240 new infection cases with SARS-CoV-2 per day were detected in China, about 24.000 in Germany and 240.000 in the United States. The Chinese government declared the province to be under martial law, Germany has a lockdown where people are asked not to travel- if they do so the should self-quarantine or maybe they risk a fine and in the United States there are various restrictions and recommendations. There is no doubt that draconic measures are most efficient in order to control the spreading of the virus, but martial law as an answer to pandemic infection is considered to be incompatible with western democratic rules and constitutions. We will have to find a way in order to reduce both the morbidity and mortality due to the pandemic and the political, socioeconomic and psychological consequences. It is known that asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 carriers can spread the infection. Asymptomatic people may carry the virus and stay asymptomatic throughout the infection or they are presymptomatic, that means they develop clinical symptoms on the day of PCR-testing or later onwards. Within a hospital, there are 6 different ways for transmission of infection:

- the symptomatic, SARS-CoV-2 positive patient to another patient (i) or to healthcare workers (HCW) (ii);

- asymptomatic patients to another patient (iii) or to asymptomatic HCW (iv) and

- finally asymptomatic HCW to other fellow HCW (v) or to asymptomatic patients (vi).

Nowadays, with deep knowledge about COVID-19 among HCWs and a vast availability of personal protection equipment, the first two possibilities play an insignificant role. Every possible routine measure is taken in order to reduce the risk of bringing COVID-19 into the hospital (iii and iv), e.g. outpatient visits are restricted to those with negative medical history for any clinical symptoms, risk factors, travel history and no fever measured at point of care; elective patients undergo an operation only if delaying operative therapy for more than three months will lead to death or irreversible deterioration of the disease and if they present with a negative PCR not older tan 72 hours; visits from friends and relatives are banned. So spread of infection by asymptomatic HCWs, infection routes (v) and (vi), is of serious concern.

2. Material and Methods

In April 2020 the local health department (Gesundheitsamt) ordered a shutdown of a teaching hospital due to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak- one index patient and five infected HCWs- and put it under quarantine. For the first time, all patients plus all employees of one German hospital (healthcare providers, physicians, and registered nurses and hospital workers) were tested to detect silent or asymptomatic carriers. The first three polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing cycles between April 3rd and April 19th were ordered by the health department (n=3.107 tests). Results were reported elewhere . From April 24th on all PCR tests in asymptomatic HCW were voluntary (n=5.887). The hospital´s administration did not encourage testing after May 2020 and reinstalled the weekly free tests during the “2nd wave”, starting September 1st for HCWs with patient contact; by December 14th n=8.994 had been performed [1,2]. All people employed by the hospital as well as by subcontractors were informed via email and notice on the bulletin board about the terms (free of charge) and conditions (voluntary) of PCR testing. The works council was informed about the voluntary nature of testing and gave their consent. Every positive HCW was reported to the health department as regulated by German law, put under quarantine, eventually received an additional certificate of disability when symptoms arouse or hospitalization was deemed to be necessary. Written consent was obtained for scientific evaluation of individual data. Furthermore, after obtaining written consent by all participants, data were reported to the health professional association (German: Berufsgenossenschaft) to indicate the possibility of occupational disease. Contacts were traced by the health department [3].

3. Results

This research letter reports the effectivity and the efficiency of repeat testing of HCWs from the April 27th until December 31st. Voluntary participation in general was low, n=245 (20,9%) on average, ranging from n=15 to n=871 per weekly interval. Positivity rates, defined as numbers of SARS-CoV-2 positive test divided by numbers of HCW times 100, tested at a given time interval, varied from 0% to 6.7%. In the beginning of April positivity was higher than in the county population or the general population of Germany. From the end of April on, with the exception of two testing dates with ridiculously low numbers of voluntary participants (September 7th and 14th), identification of SARS-CoV-positive HCWs was a rare incident, though the hospital´s patient load on both regular and intensive care wards was back up to 15% of all beds (38/250). Repeat testing detected asymptomatic as well as presymotomatic carriers [4]. The number of truly asymptomatic and not only presymptomatic cases was less than 1 per week (table 1). A total of 146 HCWs (out of 1.176) were tested positive. 29 were completely asymptomatic (19.8%), 56 were presymptomatic (38.4%) and 61 (41.8%) had symptoms of variable intensity. N=10 had to be hospitalized for 6.7 + 6.4 days (range 1-21 days), none died.

4. Discussion

The positivity rate in the hospital was significantly lower than that of the general population, proving that the measures and precautions taken to avoid SARS-CoV-2 infection within the hospital are working. HCWs working in a potentially high risk environment show a considerably higher cumulative infection rate than the general population: 83/1.172 (7.1%) compared to 4.999/154.544 (3.2%). Therefore the effectivity of repeat testing is high- low positivity in spite of higher prevalence of positive SARS-CoV-2 tests and a higher pretest probability. Repeat testing is the right thing to do, it is effective.

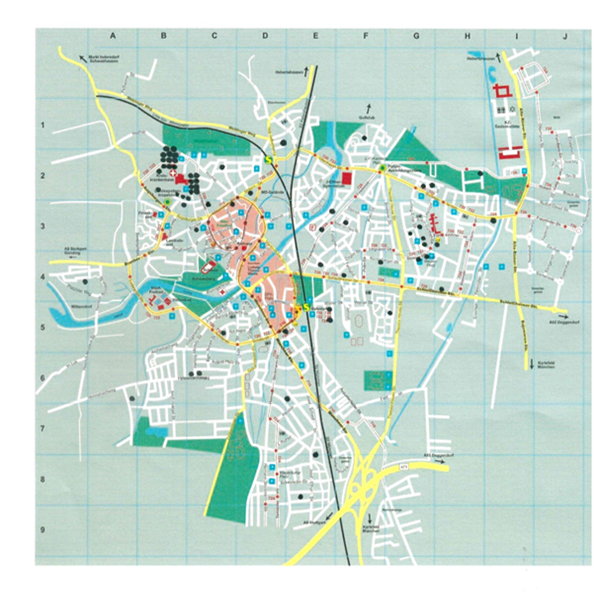

Effectivity of repeat testing is high, but efficiency is only moderate: Repeat testing works to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2 within the hospital, but the way it is done, it does not reduce the incidence and prevalence to 0. In order to be as safe as possible, testing intervals in all HCWs having close patient contact should be reduced from 7-day to 2-3 day-intervalls, based on the pathophysiology and the mean infection to symptom interval of COVID 19, especially in the light of the new VOCs (variants of concern), having a higher secondary attack rate. The Occupational Health and Safety Regulations of the trade associations (German: Berufsgenossenschaften) are insufficient to control a pandemic, because they do not cover the costs for routine repeat testing of asymptomatic HCWs. A large study in 1.838 HCW from two hospitals in Tirschenreuth, initially Germany´s Corona-hotspot, revealed a prevalence of antibody formation of 20%; of those only 48% had a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test. Efficiency is reduced by the low voluntary testing participation of HCWs and the reluctancy of the employer to invest in testing in times of low incidence of infection. The majority of COVID-infections seem to stem from private, non-professional contacts, e.g. family, friends or children. 61 out of 146 HCWs that were tested between April 3rd and today, live within the city of Dachau, 21 of those in apartments within the hospital compound (figure 1). They are younger than the rest (34 versus 40 years of age), and more likely to belong to the subgroup “registered nurse” (19/21, 90%). Those apartment houses have public washing and drying spaces in the basement, some- mostly 1 room-apartments- share a kitchen on the floor. One could speculate that even though HCWs perfectly adhere to hygiene rules during work, they may forget about precautions when they socialize. A city map like in figure 1 will be used to sensitize and communicate the problem to all HCWs. But it may also be part of the “egg or hen-discussion” do they become infected because they live there or do they live in a community with an increased rate of infected people? A COVID-free hospital seems to be a dream but- even if the stakes are high- may be accomplished by reducing transmission routes (v) and (vi) nearly to zero.

|

Date in 2020 mm.dd |

In house testing |

Positivity |

General population [5] |

|

|

nparticip |

npos |

npos/ nparticip |

||

|

4.03 |

1.171 |

36 |

3.1 |

5 to 10 |

|

4.14 |

953 |

9 |

0.9 |

5 to 10 |

|

4.19 |

983 |

7 |

0.7 |

5 to 10 |

|

4.27 |

871 |

3 |

0.3 |

3 to 5 |

|

5.04 |

776 |

4 |

0.5 |

3 to 5 |

|

5.11 |

645 |

2 |

0.3 |

2 to 3 |

|

5.18 |

255 |

0 |

0 |

2 to 3 |

|

5.15 |

216 |

0 |

0 |

1 to 2 |

|

06.01-06.30 |

229 |

0 |

0 |

0.1 to 1 |

|

07.01-07.31 |

201 |

0 |

0 |

0.1 to 1 |

|

08.01-08.31 |

186 |

0 |

0 |

0.1 to 1 |

|

9.01 |

131 |

1 |

0.8 |

0.1 to 1 |

|

9.07 |

29 |

1 |

2.6 |

0.1 to 1 |

|

9.14 |

15 |

1 |

6.7 |

0.1 to 1 |

|

9.21 |

130 |

1 |

0.8 |

1 to 2 |

|

9.28 |

56 |

0 |

0 |

1 to 2 |

|

10.05 |

80 |

1 |

1.3 |

1 to 2 |

|

10.12 |

86 |

0 |

0 |

2 to 5 |

|

10.19 |

237 |

0 |

0 |

3 to 5 |

|

10.26 |

75 |

0 |

0 |

5 to 10 |

|

11.02 |

135 |

2 |

1.5 |

5 to 10 |

|

11.09 |

120 |

0 |

0 |

5 to 10 |

|

11.16 |

411 |

7 |

1.7 |

5 to 10 |

|

11.23 |

132 |

1 |

0.8 |

5 to 10 |

|

11.3 |

249 |

1 |

0.4 |

5 to 10 |

|

12.07 |

189 |

3 |

1.6 |

>10 |

|

12.14 |

433 |

3 |

0.7 |

>10 |

|

8.994 |

83 |

|||

Figure 1: Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 positive Health Care Workers according to their home address within the city of Dachau. Every black dot represents a person tested PCR-positive. Accumulation of positive HCWs living in the hospital compound.

Funding

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest/ Competing interests

The author declares no conflicts of interest whatsoever: No benefits in any form from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript were received or will be received by the author.

Availability of data and material

All original data- anonymized are available on request.

Ethics approval

Not applicable, the author is obliged to act for HCWs with a positive PCR and to report their data after obtaining written consent to the health professional association (German: Berufsgenossenschaft) by law, following his function as the physician responsible for HCW´ health reporting

Consent to participate

Written consent was obtained for scientific evaluation of individual data and in order to report the data to the health professional association (German: Berufsgenossenschaft) to indicate the possibility of occupational disease.

Acknowledgement

Alexander von Freyburg is the hospital´s physician responsible for organisation and structural prerequisites of all aspects of COVIT-19 pandemic for his help and advice.

References

- Scherer MA, Von Freyburg A, Brücher BLDM, et al. COVID-19: SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility in healthcare workers- cluster study at a German Teaching Hospital. 6 (2020): 1-9.

- Variant Technical group: Meera Chand, Susan Hopkins, Gavin Dabrera, et al. PublicHealthEngland Crown copyright 2021 Version 1.

- Finkenzeller T, Faltlhauser A, Dietl KH, et al. A: SARS-CoV-2-Antikörper bei Intensiv- und Klinikpersonal. MedKlin IntensivmedNotfmed 115 (2021): S139-S145.

- Beate Ritz. Correspondence (letter to the editor): In Reply. Dtsch Arztebl Int 117(2020): 288.

- Germany: Coronavirus Pandemic Country Profile (2020).