Co-morbidities in Children with Severe Acute Malnutrition – A Hospital based Study

Article Information

Susheel Kumar Saini1*, Ajay Kumar Saini2, Seema Kumari3

1MBBS, MD Pediatrics (SPMCHI, Jaipur) Assistant Professor, NIMS Medical college, Rajasthan, India

2MBBS, DNB Pediatrics trainee, Sanjay Gandhi Memorial Hospital, New Delhi, India

3MBBS, MD Anaesthesiology & Critical Care, Pt. B.D. Sharma PGIMS, Haryana, India

*Corresponding Author: Dr. Susheel kumar Saini, MBBS, MD Pediatrics (SPMCHI, Jaipur), Assistant Professor, NIMS Medical college, P. No. 14, Ganesh nagar, Near kishor nagar, Murlipura, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

Received: 12 May 2022; Accepted: 19 May 2022; Published: 31 May 2022

Citation: Susheel Kumar Saini, Ajay Kumar Saini, Seema Kumari. Co-morbidities in Children with Severe Acute Malnutrition – A Hospital based Study. Journal of Pediatrics, Perinatology and Child Health 6 (2022): 296-304.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Objective: To find out the co-morbidities such as infections and micronutrient deficiencies in hospitallized children with severe acute malnutrition.

Study design: In this hospital based descriptive type of observational study, conducted at the Department of Pediatrics, SMS Medical College 125 severe acute malnourished children were included. Patients under-go relevant investigation to find out associated infectious co morbidities. Micronutrient deficiencies assessed by clinical signs. Vitamin D status assessed by laboratory test.

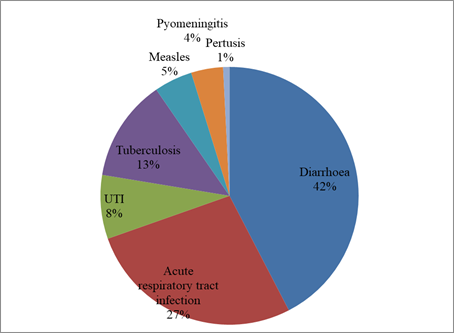

Results: 42% had diarrhea and 27% had acute respiratory tract infections as co morbid condition. Tuberculosis was diagnosed in 13% of cases. Anemia was present in 86% cases. Signs of vitamin B and vitamin A deficiency were seen in 24% and 6% cases. 97% children have inadequate vitamin D levels.

Conclusions: Timely identification and treatment of various co-morbidities is likely to break undernutrition-disease cycle, and to decrease mortality and improve outcome. Nearly all SAM patients have inadequacy of Vitamin D. So Vitamin D supplement should be given to all SAM patients.

Keywords

India, Management, Vitamin D

Article Details

1. Introduction

1.1 Objective

Malnutrition or malnourishment is a condition that results from eating a diet in which nutrients are either not enough or are too much such that the diet causes health problems [1, 2]. Not enough nutrition is called undernutrition or undernourishment while too much is called over nutrition. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), malnutrition essentially means “bad nourishment” and can refer to the quantity as well as the quality of food eaten [3, 4]. Severe acute malnutrition affects an estimated 20 million children under 5 years of age and is associated with 1-2 million preventable child deaths each year [5]. Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) results from a nutritional deficit that is often complicated by marked anorexia and concurrent infective illness [6]. Similarly, malnutri-tion increases one’s susceptibility to and severity of infections, and is thus a major component of illness and death from disease. Globally, comorbidities such as diarrhoea, acute respiratory tract infections and Malaria, which results from a relatively defective immune status, remain the major causes of death among children with SAM [7]. Anemia, Vitamin B complex deficiency, Vitamin D deficiency, Vitamin A deficiency, Scurvy are the common micronutrient deficiencies seen in severe acute malnourished Children [8].

This study was carried out to find out demographic data and co-morbidities such as infections and micronutrient deficiencies in children with severe acute malnutrition.

2. Methods

This study was conducted in the Department of Pedia-tric Medicine, Sir Padampat Mother and Child Health Institute, attached to SMS Medical College, Jaipur from May 2020 to April 2021. A total of 125 cases presenting with severe acute malnutrition were enroll-ed of age 6 to 59 months. Severe acute malnutrition among children of six to fifty nine month of age is defined by WHO and UNICEF as any of the following [9] –

- Weight for height below -3 standard deviation of median WHO growth reference

- Mid upper arm circumference below 11.5 cm

- Presence of bipedal oedema

- Visible severe wasting

Children whose guardians refuse to give positive consent and those who died before taking necessary investigations were excluded. Children with major congenital malformations and those with chronic sys-temic diseases such as chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease were also excluded. This study was descriptive type of observational study. The clinical and the demographic information were recorded on a pre-structured proforma, together with the detail history, physical and detailed systemic examination. Weight, length/height, Mid-Upper Arm Circumfer-ence (MUAC) and weight for height/ length were determined from each study participant. Socioecono-mic status of study subjects was assessed as advised by Modified Kuppuswamy scale of social classifica-tion which is based on occupation, education of the parents and income of the family [10]. Contact with tuberculosis was determined by either contact with open case of pulmonary tuberculosis recently or if there is history that the child was in contact of open case of tuberculosis in last two year of time. Immunization status of study subjects was assessed as per schedule of National Immunization Programme (NIP) [11].

Infectious comorbidities defined as per following criteria –

- Diarrhoea was defined as three or more loose stools per day for any time duration. Persis-tent diarrhoea was defined as an episode of diarrhoea, of presumed infectious etiology, which starts acutely but lasts for more than 14 days. Chronic diarrhoea was defined as insidious onset diarrhoea of >2 weeks duration in children.

- Acute respiratory tract infection was defined as short duration of cough (< 2 weeks) or respiratory difficulty, age-specific fast brea-thing (above normal for age category), aus-cultatory and/or chest x-ray findings.

- UTI (Urinary tract infection) was diagnosed on the basis of suggestive clinical symptoms along with positive urine culture report.

- Measles was defined as generalized maculo-papular rash lasting for ≥ 3 days, fever (≥ 38.3°C, if measured) along with cough, coryza (i.e. runny nose) or conjunctivitis (i.e. red eyes).

- Meningitis was diagnosed on the basis of suggestive clinical features and confirmed by CSF examination and neuroimaging. IAP algorithm was applied to diagnose the tuber-culosis in children in this study [12].

- Micronutrient deficiencies were assessed by clinical signs during general physical exami-nation in these children except Vitamin D status which was determined by laboratory test.

- Anaemia was defined on the basis of WHO reference values of hemoglobin (Hb) in children in age group of 6 to 59 months-[13].

|

Anemia |

Hb level (gm/dl) |

|

Mild Moderate Severe |

10 -10.9 7 – 9.9 < 7 |

Vitamin A deficiency defined clinically by presence of night blindness, Bitot’s spots, corneal xerosis and/ or ulcerations, corneal scars caused by keratomalacia. Vitamin B complex deficiency defined clinically by presence of angular stomatitis, cheilosis, glossitis, dermatitis, tingling/numbness in the extremities. Scurvy defined clinically by gum bleeding, loose teeth, Joint pains, Dry scaly skin, delayed wound-healing with suggestive findings of X-ray long bones. Vitamin D status (25 Hydroxy Vitamin D) in study subjects was determined by laboratory test by chemil-uminescence method using ADIVA CENTOR XP machine. Vitamin D level <10ng/ml was defined as deficient, 10 - 29 as insufficient while ≥30 as adequate level. A written, informed consent was obtained from parents. Clearance from Departmental Ethics Commi-ttee was taken prior to the start of the study. All participants had the option to withdraw from the study anytime during their hospital stay. All filled questionnaires were checked and coded on Microsoft Office Excel Worksheet and any missing data or information was actively searched from patient’s files. Descriptive cross tabulations were formed to examine for associations.

3. Results

In this study 125 children with severe acute malnutri-tion were included. The mean age of presentation was 20.4 months. Among study population 35 (28%) children were of age group 6 – 12 month. 66 (52.8%) children related to age group 13 – 24 month while 24 (19.2%) children belonged to age group of 25 – 59 month. Among the children 49 (39%) were female while 76 (61%) were male. Ratio of male to female patients was 1.6:1. Among the cases 107 (86%) had weight for height <- 3SD, 50 (40%) children had visible severe wasting, 102 (82%) had mid upper arm circumference < 11.5 cm, while 20 (16%) had bilateral pitting oedema of nutritional origin. 30 (24%) were completely immunized, 82 (65%) were partially immunized while 13 (10%) were unimmunized. Most of the children were belonged to lower socio economic class. 87 (70%) children belonged to upper lower class, 35 (28%) belonged to lower middle class while 3 (2%) children belonged to upper middle class. 83 (66%) children had the history of recurrent hospita-lization; either by same illness or other illness. History of contact with tuberculosis was present in 17 (14%) children. 95 (76%) children were found to receive exclusive breast feeding till 6 month of age. While complimentary feeding started in only 31 (25%) children at 6 month of age.

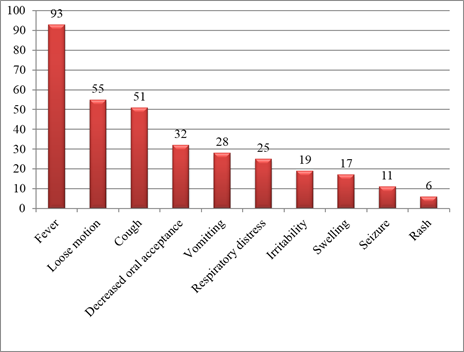

The most common presenting complaint which was seen in current study was fever. That was present in 93 (74.4%) of cases. Other presenting complaints in study subjects were loose motion in 55 (44%), cough in 51 (40.8%), decreased oral acceptance in 32 (25.6%), vomiting in 28 (22.4%).25(20%) children presented with Respiratory distress. Other presenting complaints were irritability in 19 (15.2%) children, swelling over body either localized or generalized in 17 (13.6%) children, Seizures of any type in 11 (8.8%) children and rashes over body in 6 (4.8%) children. Diarrhoea was found to be most common infectious co-morbidity. That was present in 53 (42%) of children. Among 53 cases of diarrhoea, 38 (71.6%) had acute diarrhoea, 9 (16.9%) had chronic diarrhoea while 6 (11.3%) had persistent diarrhoea. Acute respiratory tract infections were second most common co-morbidity which was seen in 34 (27%) children.16 (13%) children had tuberculosis as co-morbid condition. Out of 16 children 9 had pulmonary tuberculosis while 7 children had tubercular meningitis. UTI was diagnosed in 12 (8%) children. Out of 12 children diagnosed to have UTI; 5 children had growth of E. coli, 3 children had Candida while other had CONS, COPS, Enterobacter and Pseudomonas (one case each). Measles was seen in 6 (5%) children. Pyomeningitis was diagnosed in 5 (4%) children. Among the study subjects 108 (86%) children were found anemic. Out of 108 anemic patients; 17 (15.7%) children had mild anemia, 54 (50%) had moderate anemia while 37 (34.2%) children had severe anemia. Vitamin A deficiency was present in 6 (5%) children. Vitamin B complex deficiency seen in 24 (19%) children while scurvy seen in 2 (1.6%) of children. Inadequate levels of Vitamin D were present in 121 (97%) children.

(UTI – Urinary tract infection)

|

Patients, No. (%) |

125 (100%) |

|

Age group, No. (%) 6 – 12 month 13 – 24 month 25 – 59 month |

35 (28%) 66 (52.8%) 24 (19.2%) |

|

Sex, No. (%) Female Male |

49 (39%) 76 (61%) 1:1.6 |

|

Immunization status Completely immunized Partially immunized Not immunized |

30 (24%) 82 (65%) 13 (10%) |

|

Socioeconomic status Upper lower Lower middle Upper middle |

87 (70%) 35 (28%) 3 (2%) |

|

History of recurrent hospitalization |

83 (66%) |

|

Exclusive breastfeed till 6 month of age |

95 (76%) |

|

Complimentary feeding started at 6 month of age |

31 (25%) |

|

History of contact with tuberculosis |

17 (14%) |

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of study subjects.

|

Patients, No. (%) |

125 (100%) |

|

Anemia Mild Moderate Severe |

108 (86%) 17 (14%) 54 (43%) 37 (30%) |

|

Vitamin A deficiency |

6 (5%) |

|

Vitamin B complex deficiency |

24 (19%) |

|

Scurvy |

2 (1.6%) |

|

Vitamin D status Deficient Insufficient Adequate |

42 (34%) 79 (63%) 4 (3%) |

Table 2: Micronutrient deficiencies in study subjects.

4. Discussion

Severe acute malnutrition is a well recognized emerg-ency situation with substantial morbidity and mortali-ty that requires immediate and effective treatment. Prompt initiation of appropriate treatment of both complications such as hypoglycemia, hypothermia, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, infections and the underlying cause can significantly reduce associated morbidity and mortality. Most of the studies are related to infectious co-morbidities while only few studies are related to micronutrient deficiencies in severely malnourished children. Mean age of children reporting with malnutrition was similar to other studies and there was significant male predominance in malnourished children [14]. This may be due to ignorance about the health checkups of female children. So that they reach to the health facilities less than the boys. However, no definite causal relation-ship was found for this male preponderance. Our study show less coverage of immunization in our study area which is likely due to ignorance and unawareness about immunization.

In our study about two third children had the history of recurrent hospitalization; either by same illness or other illness. In study by Yoann Madec el al [15] history of recurrent hospitalization was present in 4.7 % children only. Unhygienic living conditions and poor socioeconomic status may be the cause of increa-sed rate of hospitalization in our study subjects. Rate of exclusive breast feeding found to be more in our study but weaning not started at recommended age which is predisposing factor for malnutrition. In present study, Diarrhoea was found to be the most common infectious co-morbidity. Acute respiratory tract infections were found to be the second most common co-morbidity followed closely by tuber-culosis. In a Colombian study, 68.4% of malnourished children were suffering from diarrhea and 9% had sepsis at the time of admission [16]. Two African studies also showed high incidence of diarrhea in SAM children of 49% and 67% [17, 18]. Though previous reports have described malnutrition as an important risk factor for pneumonia than for diarrhea [19], diarrhea was the major co-morbid condition found in our study. A study from Africa [20] also reported a comparable incidence of respiratory illness and tuberculosis (18% each) in admitted SAM children. Measles has severe consequences on the nutritional status. A previous Indian study [8] showed only 3.8% of children with past history of measles but we found a higher proportion. Malaria and HIV infection were previously reported as major co-morbidities with total prevalence of 21% and 29.2%, respectively [21] but in our study malaria, HIV were not found to be as co-morbid condition.

Overlapping nature of protein–energy malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies is well understood and it is seen that lack of one micronutrient is typically associated with deficiency of others [22]. Anemia and vitamin D deficiency were the two most common micronutrient deficiencies associated with malnut-rition in our study, and this is consistent with the previous reports [23]. In previous studies vitamin D status is accessed by clinical examination and radio-logical findings but in our study vitamin D status is accessed by laboratory test. So we found higher incidence of Vitamin D deficiency. Absence of a comparative group, no biochemical evaluation for micronutrient deficiencies and non-assessment of contributing factors for these deficiencies were the main lacunae of the study. Our institute is the only referral centre and the major hospital that provides primary to tertiary care for children in this region. The geographic location of our hospital may have led to an enrollment bias. Our study suggest that malnutrition is predicted by age less than two years, failure to start complimentary feeding at recommended age, recur-rent hospitalization, taking unbalanced diet, lack or incomplete immunization and lower socioeconomic status.

5. Conclusion

Apart from nutritional rehabilitation, timely identify-cation and treatment of co-morbidities like diarrhea, acute respiratory tract infection, anemia and micronu-trient deficiencies is vital in malnourished children, so as to break undernutrition-disease cycle, and to decre-ase mortality and to improve outcome. Nearly all SAM patients have inadequacy of Vitamin D. So Vitamin D supplement need to be given to all SAM patients.

References

- ‘Malnutrition’ in Dorland's Medical Dictio-nary, 31st ed: USA: Elsevier (2004).

- Facts for life (PDF) (4th ed.). New York: United Nations Children's Fund (2010).

- Malnutrition, Water Sanitation and Health

- J. Gibney et al, Clinical Nutrition, Wiley-Blackwell (2005).

- World Health Organization. WHO, UNICEF, and SCN informal consultation on commu-nity-based management of severe malnutri-tion in children, SCN Policy Paper No. 21. Geneva: World Health Organization (2006).

- Manary M J, Sandige H L. Management of acute moderate and severe childhood malnutrition. BMJ 337 (2008): a2180.

- Black R E, Cousens S, Johnson H L, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 375 (2010): 1969-1987.

- Rakesh kumar, Jyoti singh, Karan joshi, et al. Co-morbidities in Hospitalized Children with Severe Acute Malnutrition (2013).

- World Health Organization. Management of Severe Malnutrition: A Manual for Physi-cians and Other Senior Health Workers. World Health Organization (1998).

- Ravi Kumar BP. Kuppuswamy’s Socio-Economic Status Scale - a revision of economic parameter for 2012. International Journal of Research & Development of Health 1 (2013): 2-4.

- Vinod k Paul, Arvind Bagga. Essential pediatrics, National immunization program-mme (2017).

- Working group on tuberculosis. Consensus statement on childhood tuberculosis. Indian pediatr 47 (2010): 41-55.

- Bachou H, Tylleskär T, Deogratias H, et al. Bacteraemia among severely malnourished children infected and uninfected with the Human immunodeficiency virus-1 in Kam-pala, Uganda. BMCInfect Dis 6 (2006): 160.

- Madec Y, Germanaud D, Maya-Alvarez V, et al. HIV Prevalence and Impact on Renut-rition in Children Hospitalised for Severe Malnutrition in Niger: An Argument for More Systematic Screening. PloS one 6 (2011): 22787.

- Bernal C, Velásquez C, Alcaraz G, Botero J. Treatment of severe malnutrition in children: Experience in implementing the world health organization guidelines inturbo, Colombia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 46 (2008): 322-328.

- Talbert A, Thuo N, Karisa J, et al. Diarrhoea complicating severe acute malnutrition in Kenyan children: A prospective descriptive study of risk factors and outcome. PLoS One 7 (2012): 1.

- Irena AH, Mwambazi M, Mulenga V. Diarrhea is a major killer of children with severe acute malnutrition admitted to inpatient set-up in Lusaka, Zambia. Nutrition J 10 (2011): 110.

- Berkowitz FE. Infections in children with severe proteinenergy malnutrition. Pediatr Infect Dis J 11 (1992): 750-759.

- Sunguya BF, Koola JI, Atkinson S. Infections associatedwith severe malnutrition among hospitalised children in East Africa. Tanzania Health Research Bulletin 8 (2006): 189-192.

- Sunguya B. Effects of Infections on Severely Malnourished Children in Kilifi-Mombasa and Dar es Salam : A Comprehensive Study . Dar es salaam Medical Students Journal 14 (2006): 27-35.

- Bhaskaram P. Measles and malnutrition. Indian J Med Res 102 (1995): 195-99.

- Ejaz MS, Latif N. Stunting and micronutrient deficiencies inmalnourished children. J Pak Med Assoc 60 (2010): 543-547.