Cognitive Reserve Can Be Induced Through Environmental Enrichment in Aged Organisms: Testing the Hypothesis in Animal Models

Article Information

Edvaldo Soares1*orcid, Luã Carlos Valle Dantas2orcid, Rafael Antonio Peres Borba3orcid, Alex Bacadini França4orcid

1PhD. Neurosciences, São Paulo State University-UNESP, Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory-LaNeC, Avenue Hygino Muzzi Filho, 737, Brazil

2Doctor of Psychology, Faculdade Cristo Rei-FACCREI, Brazil

3Medical student, Faculdade de Medicina de Marília-FAMEMA, Brazil

4PhD. Psychology Federal University of São Carlos-UFSCar Laboratory of Human Development and Cognition - LADHECO Washington Luís km 235 - SP-310, Brazil

*Corresponding authors: Edvaldo Soares, PhD. Neurosciences, São Paulo State University-UNESP, Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory-LaNeC, Avenue Hygino Muzzi Filho, 737, Brazil.

Received: 30 August 2025; Accepted: 04 September 2025; Published: 06 November 2025

Citation: Edvaldo Soares, Luã Carlos Valle Dantas, Rafael Antonio Peres Borba, Alex Bacadini França. Cognitive Reserve Can Be Induced Through Environmental Enrichment in Aged Organisms: Testing the Hypothesis in Animal Models. Journal of Biotechnology and Biomedicine. 8 (2025): 345-355.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

We tested whether cognitive reserve, assessed using a spatial memory paradigm, is limited to early life and maintained throughout the lifespan, or whether environmental enrichment applied only during aging can also induce cognitive reserve in animal models. Using Wistar albino rats (n = 48) randomly distributed into four groups (control 1 and 2, and experimental 1 and 2), experimental group 1 was subjected to environmental enrichment only during childhood, and experimental group 2 only during aging, while their respective control groups did not receive environmental enrichment. After two phases of spatial memory assessment using the Morris Water Maze (MWM), the groups exposed to an enriched environment outperformed their respective controls, with experimental group 1 showing a slight advantage over experimental group 2. These findings reinforce the cognitive reserve hypothesis, supporting the importance of early cognitive development, but also demonstrating that cognitive reserve can be induced even in aged organisms.

Keywords

Cognitive Reserve; Environmental Enrichment; Aging; Plasticity; Spatial Memory

Article Details

Introduction

The preservation of cognitive capacity in aging is one of the greatest challenges in science. Cognitive processing, including memory processing in humans [1-3] and non-humans [4, 5], begins to decline [6-8]. Cognitive deficits resulting from aging can be attributed to the reduction of labile synaptic structures in the brain [9], leading to decreased plasticity [10] . Studies reporting changes in brain structure and function have long indicated that aging leads to brain atrophy [11-15], particularly in the prefrontal córtex [16, 17] and hippocampus [18-20]. However, despite evidence of the negative impacts of aging, considerable heterogeneity in cognitive trajectories is observed in elderly individuals, even in those with degenerative brain pathologies [21], which can overshadow the non-pathological aging process [22].

One hypothesis to explain this heterogeneity in cognitive trajectories is that of "cognitive reserve" (CR) [23-25]. CR is a theoretical construct proposing the existence of a capacity, shaped by innate or genetic differences and life experiences, that exerts a protective function against cognitive decline due to degenerative brain pathologies or normal aging [22, 26]. In other words, CR consists of the cognitive resources accumulated and utilized at a given time, determining an individual's general cognitive capacity [27]. Related to CR is the concept of brain reserve (BR) [26, 28], which refers to neurobiological resources, such as brain size and cortical thickness, available at a specific moment [27].

While BR assessment appears more objective, CR assessment is less straightforward. Educational level [29, 30], despite controversial results [31, 32] and limitations [26], has commonly been used as a parameter for CR, along with tests aimed at assessing general cognitive ability (GCA) [33].

Despite the difficulties that the CR concept still presents, several questions arise:

- Is there the possibility of a non-invasive intervention that promotes CR and induces plasticity, acting as a protective factor against cognitive decline from pathology or normal aging, and serving as a basis for interventions in the elderly?

- If there is a method to stimulate CR, when should it be initiated?

iii. Would stimulation, even if started in later life, yield significant improvements in cognitive performance, indicating CR induction?

Assuming that an intervention promoting CR, which acts both as a protective and interventional factor, is possible, and that stimulation should ideally begin in childhood, positive results can still be observed when initiated later. However, given the complexity of testing these hypotheses in humans, due to factors such as general health, mental health, culture, diet, physical activity, and social interaction, we opted to test these hypotheses at a basic behavioral level using animal models.

To explore these questions and test our hypotheses, we adopted the environmental enrichment (EE) model. EE is defined as the addition of diverse social, physical, and somatosensory stimuli to the environment [34]. This model was selected because previous research has demonstrated that EE has positive neurophysiological impacts, promoting structural and neurochemical changes, including increased neuronal body size, enhanced glial activity, altered metabolic activity, and neurogenesis in the hippocampus, as well as an increase in dendrite number and length, which supports synapse formation [35-40]. EE was also chosen because it has been shown to positively affect learning and memory [37, 40, 41], contributing to the preservation of spatial memory [42, 43]. In this study, spatial memory assessment was considered a model for evaluating CR in animals, including humans [44].

This research aims to investigate, based on the environmental enrichment model, whether cognitive reserve, assessed through the spatial memory paradigm, is limited to early life and persists throughout the lifespan, and whether environmental enrichment applied only during aging can also induce cognitive reserve in animal models.

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats from the bioterium of the Faculty of Medicine of the Universidade Estadual Paulista were used (n = 48). The experiment began after weaning, when the animals were 40 days old. They were housed socially for 46 days. After this period, the animals were randomly distributed into four groups of equal size: childhood control group (G1), childhood experimental group (G2), elderly control group (G3), and elderly experimental group (G4). Animals in the control groups [G1 (n = 12) and G3 (n = 12)] were not exposed to environmental enrichment (EE), while those in the experimental groups [G2 (n = 12) and G4 (n = 12)] were exposed to EE. The age of rats was scaled based on human experimental studies suggesting a 1:30 human-to-rat correspondence [45, 46].

Environmental Enrichment

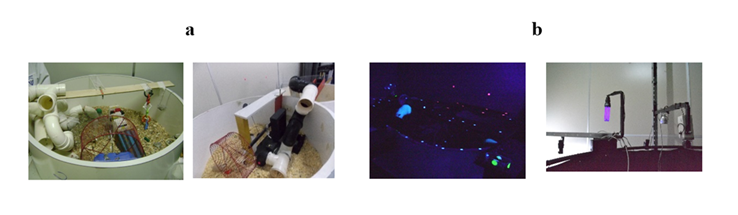

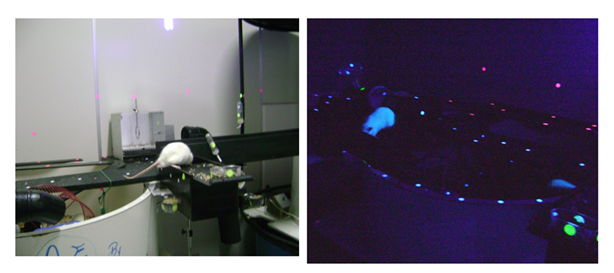

Environmental enrichment (EE) was implemented using manufactured apparatuses, consisting of two open fields (1.50 m in diameter and 50 cm in height) where various objects were placed and illuminated with black light. This was done to: (i) respect the rat's wake-sleep cycle [47], (ii) stimulate the animals' movement and exploration, and (iii) avoid unnecessary levels of stress [48-50]. Considering that Wistar rats have nocturnal habits, the environment was illuminated with black light during the experimental procedures. The open fields contained various objects with different textures, shapes, and sizes, some of which produced sounds when moved. The space was designed to provide challenges (e.g., climbing a platform, navigating a tunnel, touching a suspended object) to obtain food.

All animals (n = 48) were deprived of food for 8 hours before the EE sessions, with no water deprivation. During the EE sessions, sunflower seeds were randomly hidden in the environment. Animals not subjected to EE (G1 and G3) also received seeds in their cages located in the animal maintenance room. In each field, six animals were initially placed, and the environments were modified every five sessions (Fig. 1).

During the first ten EE sessions, the fields were isolated, and from the 11th session onwards, they were interconnected (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Interconnected open fields used for EE. The interconnected open fields were used from the 11th EE session onwards. The materials used in the EE camps were changed every five sessions/days. In Phase I, the EE sessions for G2 subjects started at 6:30 PM, respecting the circadian cycle of the research subjects.**

The animals in G2 were exposed to EE for 30 sessions, considered ideal [51,52], from 46 to 83 days of life, while animals in G4 were exposed for 30 sessions from 470 to 517 days of life. The EE sessions began at 6:30 PM, lasting for 120 minutes. After each EE session, the animals were placed back in their respective maintenance boxes (plastic cages with metal bars [33 x 40 x 17 cm]). They were kept in an animal maintenance room suitable in size and cleanliness, maintained at an average temperature of 21º to 23ºC, with an exhaust system. The lighting in the maintenance room was divided into two cycles: 12 hours of light and 12 hours of dark. The rats received a balanced diet developed specifically for rodents (Nuvilab) and had ad libitum access to water.

Spatial Memory Assessment

To assess retention and formation of spatial memory, the Morris Water Maze (MWM) was used [51]. The MWM was constructed from a circular polyethylene box, 200 cm in diameter and 50 cm in depth. The inner walls of the MWM were black to ensure homogeneity. Distal cues (symbols of different colors measuring 20 x 20 cm) were arranged above the water. According to the recommended experimental model [53, 54], the animal should locate a submerged escape platform, constructed of acrylic and measuring 9 cm in diameter, located 1.5 cm below the water level.

To obtain performance measures, the MWM procedure was organized into four stages: (i) recognition pre-training, (ii) pre-training with a visible platform, (iii) training with an invisible platform, and (iv) testing. In the recognition pre-training (i), the animals were individually placed on a platform for 30 seconds to habituate them to the environment and help them understand where the platform, arranged at the same water level, was located. This strategy allowed the animal to form a spatial representation of the environment. For pre-training with a visible platform in MWM (ii), conducted 24 hours after recognition pre-training, the animals were individually placed in the water by hand and submerged until they began to swim independently; at this point, timing commenced.

From that moment, the animal had 60 seconds to climb onto the platform submerged at 1.5 cm. Each animal underwent one attempt in each of the MWM quadrants, totaling four attempts per animal. Training with an invisible platform (iii) occurred 24 hours after the previous procedure. In this training, the same protocol as the pre-training with a visible platform was followed, except that the water was dyed with non-toxic black gouache paint, preventing visual identification of the platform.

The MWM test was conducted eight days after training with the invisible platform, an interval considered sufficient, based on literature data, to evaluate the consolidation of long-term memory [53, 55-58]. The animals underwent one trial in each of the MWM quadrants (total = 4 insertions). Performance was assessed based on the time, in seconds, it took the animal to reach the platform.

The experimental design comprised two phases (P1 and P2), with two tests applied in each phase. In Phase 1, control group 1 (G1) and experimental group 1 (G2) were tested at 111 days of age (Test 1 – T1) and again at 372 days of age (Test 2 – T2). In Phase 2 (P2), all groups (G1, G2, G3, and G4) were tested at 525 days of age (T1) and then subjected to a new test in the MWM at 603 days of age (T2).

Individual results regarding the time to complete the MWM task were manually timed and recorded in the database. The procedures in the MWM were filmed, and the image records were stored in an image bank for analysis using the Field Monitoring System software (Field Monitor Software – Insight – EP 163 adapted for Water Maze by Insight Research and Teaching).

The study was conducted in accordance with the standards recommended by the Brazilian College of Animal Experimentation (COBEA), which defines principles of laboratory animal care, and NIH guidelines for the use of laboratory animals. The ethical protocol aligns with ARRIVE guidelines (ARRIVE 2.0 checklists). The research protocol was approved by the National Council for the Control of Animal Experimentation – COCEA – Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation – Brazil.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using multilevel linear modeling [59, 60]. The outcome was transformed to a logarithmic scale to stabilize the residual variance. Time, on a logarithmic scale, was modeled as a linear function of the trial number at the first level of the model. The intercept and slope of this linear function were modeled to vary for each animal. The expected values of the intercepts and slopes were conditioned on the group, stage, and test in which each set of trials was conducted, as well as their interactions, at the second level of the model [60].

The model was adjusted using Bayesian inference, utilizing the Stan Hamiltonian Monte Carlo Sampler - version 2.19.2 [61]. The prior distributions for the parameters were chosen to be weakly informative, reducing their influence on the inferences made [62].

Eight chains were simulated with 2,000 iterations each, with 750 iterations for warming up and algorithm adjustment, resulting in a total of 10,000 samples from the posterior distribution. Chain convergence was evaluated using the R-hat mixing coefficient, indicating that all parameters achieved acceptable convergence (below 1.1).

From the coefficients obtained by the multilevel model, contrasts of interest were computed considering the average difference between each line in the adjusted model [60]. These contrasts are presented throughout the results as point estimates based on the mean of the posterior distribution and a 95% credibility interval based on the quantiles of the posterior distribution. Since it is a linear model with the outcome on a logarithmic scale, the exponentiation of the contrast coefficients allows for evaluating the multiplicative increase of the compared groups.

Subsequently, effect sizes were calculated to assess the magnitude of the environmental enrichment (EE) effects in the two phases and their respective tests. Comparisons were made between the groups: G1 x G2; G1 x G4; G3 x G2; G3 x G4; G1 x G3; and G2 x G4. To isolate the effect of the procedures on MWM, effect sizes were calculated by comparing the groups independently in the different phases of the study (G1 x G1; G2 x G2; G3 x G3; and G4 x G4). Hedges’ g (h*) was used to calculate the effect size, considering the independence and small size of the independent groups [63, 64] (small sample bias). Pooled effect sizes were determined with standardized mean differences (SMDs). An interpretation similar to Cohen's was used for effect parameters: 0.2 - 0.49 - small effect; 0.5 - 0.79 moderate effect; and above 0.8 large effect. The overlap was calculated considering a 95% confidence interval (CI) [65-67].

Results

The data presented in Table 1 show the average time in seconds to complete the MWM task for each group (G1, G2, G3, and G4) in the two phases of the study.

|

Phase 1 (P1) |

Phase 2 (P2) |

||||

|

Test 1 (T1) |

Test 2 (T2) |

Test 1 (T1) |

Test 2 (T2) |

||

|

(111 dias) |

(372 dias) |

(525 dias) |

(603 dias) |

||

|

Groups (n=) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Groups (n=)* |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

|

G1 (12) |

10,60 (8,34) |

11,20 (12,7) |

G1 (7) |

30,6 (29,5) |

14,4 (17,4) |

|

G2 (12) |

3,56 (2,51) |

3,02 (2,65) |

G2 (10) |

4,4 (2,46) |

3,03 (1,37) |

|

G3 (12) |

G3 (7) |

18,1 (13,2) |

15,4 (17,2) |

||

|

G4 (12) |

G4 (8) |

5,1 (3,66) |

4,80 (2,74) |

||

|

* The number of animals was reduced in Phase II due to death. |

|||||

Table 1: Average time in seconds in MWM for each of the four groups in two phases.

The data indicate that groups exposed to an enriched environment (EE) demonstrated a difference in task completion speed compared to non-exposed groups. Subjects in the EE exposure condition during Phase I, on average, completed the task in less time than those who were not exposed. Subsequently, in Phase II, subjects exposed to EE, regardless of exposure age, completed the task in less time on average than non-exposed subjects (Table 1). Figure 3 displays the estimates based on the mean of the posterior distribution and a 95% credibility interval derived from the quantiles of the posterior distribution for each subject group.

Inspection of Figure 3 suggests that in Phase I (P=1), G2 performed better than G1 in both the first test (T1) (Mean = -1.07, 95% CI = [-1.4, -0.74]) and the second (T2) (Mean = -1.34, 95% CI = [-1.68, -1.01]), indicating that G2 completed the task, considering the average across four attempts, in approximately 34.3% and 26.2% of the average time taken by G1 subjects for each test, respectively, in the first phase.

G2's superior performance over G1 was consistent in Phase II (P=2), in both tests (T1: Mean = -1.58, 95% CI = [-1.97, -1.19]; T2: Mean = -1.14, 95% CI = [-1.52, -0.76]). The contrasts indicate that the magnitude of the performance difference is similar to that observed in Phase I (P=1), with G2 requiring, on average, 20.6% and 31.9% of the time taken by G1 to complete the task in tests T1 and T2, respectively.

Similarly, G4 also showed better average performance in task resolution time when compared to both G3 (T1: Mean = -1.15, 95% CI = [-1.56, -0.74]; T2: Mean = -0.97, 95% CI = [-1.38, -0.56]) and G1 (T1: Mean = -1.53, 95% CI = [-1.94, -1.13]; T2: Mean = -0.73, 95% CI = [-1.19, -0.29]). Compared to G3, G4 required, on average, 31.8% and 38.0% of the time needed; performance was similarly enhanced when compared to G1, with G4 requiring 21.7% and 47.9% of the time taken by G1 in each test.

To evaluate the impact of EE exposure at different developmental stages, the difference between G2 and G1 was compared to that between G4 and G3 (i.e., the gain in task completion time when experimental groups are compared to their respective control groups).

Comparing the difference between G2 and G1 in the first test (T1) of Phase I (P=1) with the difference between G4 and G3 in the first test (T1) of Phase II (P=2), the difference between these was nearly zero (Mean = -0.08, 95% CI = [-0.61, 0.45]). The magnitude of the difference remains similar when comparing the difference between G2 and G1 in the first test (T1) of Phase II (P=2) (Mean = 0.02, 95% CI = [-0.62, 0.65]).

Similar comparisons, using the second test (T2) in both phases (P=1 and P=2), suggest a slight advantage of G2 over G4 (Comparison of performance in P=1 and P=2: Mean = 0.37, 95% CI = [-0.16, 0.91]; Comparison in P2: Mean = 0.17, 95% CI = [-0.39, 0.73]). However, the uncertainty in these estimates prevents concluding a significant difference between groups. These results are depicted in Figure 4.

In addition, Hedge's g (g*) was used to calculate the size of the EE effect in conjunction with spatial memory assessment procedures in the MWM (pre-training recognition, visible platform pre-training, invisible platform training, and tests) for the groups (G1, G2, G3, and G4) across both study phases. The results are shown in Table 2.

|

Phase 1 |

Phase 2 |

||||

|

Test 1 |

Test 2 |

Test 1 |

Test 2 |

||

|

(111 dias) |

(372 dias) |

(525 dias) |

(603 dias) |

||

|

|

Hedges’g |

Hedges’g |

Hedges’g |

Hedges’g |

|

|

[% Overlap] |

[% Overlap] |

[% Overlap] |

[% Overlap] |

||

|

G1 x G2 |

1,14 [35,1] |

0,89 [47,4] |

1,39 [31,8] |

1,02 [38,9] |

|

|

G1 x G4 |

1,26 [33,9] |

0,80 [53,0] |

|||

|

G3 x G2 |

1,62 [22,3] |

1,13 [34,8] |

|||

|

G3 x G4 |

1,39 [31,8] |

0,96 [43,2] |

|||

|

G1 x G3 |

0,54 [55,8] |

0,05 [93,5] |

|||

|

G2 x G4 |

0,22 [57,9] |

0,84 [44,8] |

|||

|

IC95% |

|||||

Table 2: Effect size of environmental enrichment combined with spatial memory measurement procedures in the MWM across two phases.

The data indicate that environmental enrichment (EE) combined with spatial memory assessment procedures in the MWM produced a large effect size, with overlap below 50%, when comparing groups G1 and G2 in the respective tests of phases 1 and 2, as well as when comparing groups G2 and G3 and G3 and G4 in Phase 2 tests. For control groups (G1 and G3), effect size was moderate, with overlap above 50% for Test 1 – Phase 2, and small, with overlap above 90%, for Test 2 – Phase 2. However, the comparison between experimental groups (G2 and G4) indicated a small effect size with overlap above 50% for Test 1 and a large effect size with overlap below 50% for Test 2.

Furthermore, to isolate the effect size magnitude, Hedge's g was calculated for paired comparisons within groups across the two phases and respective tests (Table 3).

|

Comparisons |

GI x G1 |

G2 x G2 |

G3 x G3 |

G4 x G4 |

|

Hedges’g |

Hedges’g |

Hedges’g |

Hedges’g |

|

|

[% Overlap] |

[% Overlap] |

[% Overlap] |

[% Overlap] |

|

|

|

||||

|

P1T1 x P1T2 |

0,055 [94,5] |

0,209 [55,0] |

||

|

P1T1 x P2T1 |

1,065 [40,7] |

0,337 [61,5] |

||

|

P1T2 x P2T1 |

0,956 [43,0] |

0,537 [55,5] |

||

|

P1T2 x P2T2 |

0,220 [57,9] |

0,004 [96,3] |

||

|

P2T1 x P2T2 |

0,668 [54,4] |

0,688 [56,0] |

0,176 [74,8] |

0,092 [84,6] |

Table 3: Effect size related to MWM procedures based on paired comparisons between groups.

Results suggest that MWM spatial memory assessment procedures, when isolated and analyzed through intragroup comparison across study phases and tests, generally produced small effects (G1 x G1 / P1T1 x P1T2, P1T2 x P2T2; G2 x G2 / P1T1 x P1T2, P1T1 x P2T1, P1T2 x P2T2; G3 x G3 / P2T1 x P2T2, and G4 x G4 / P2T1 x P2T2). Moderate effects were found in G1 x G1 / P2T1 x P2T2 and G2 x G2 / P2T1 x P2T2 comparisons, with large effect sizes for G1 x G1 in the first phase (P1T1 x P2T1 and P1T2 x P2T1). However, these effects were negative, indicating performance declines in the analyzed phases/tests (Table 1). Performance declines were also observed for G1 in P1T1 x P1T2 and for G2 across phases P1T1 x P2T1, P1T2 x P2T1, and P1T2 x P2T2.

Discussion

This study examined the effects of environmental enrichment (EE) on spatial memory performance in both young and aged rats. We used this paradigm to assess whether cognitive reserve (CR), evaluated through a spatial memory paradigm, is limited to early life stages or can be extended throughout life. Additionally, we explored whether EE introduced solely during aging could also induce CR.

The findings from the initial phase of the experiment (P=1/T1) show that EE applied during childhood generates immediate, positive impacts. These results align with the brain reserve (BR) hypothesis, which suggests that EE induces structural and functional remodeling of synapses, thereby enhancing learning and memory capabilities [68-74] and providing neuroprotective benefits [75-77]. Beyond these immediate effects, data from the first phase (P=1/T2, P=2/T1, and T2) further indicate that the benefits of EE are long-lasting [78-81]. These observations support the hypothesis that EE promotes brain plasticity and serves as a protective factor against cognitive decline associated with both normal and pathological aging [82, 83]. Notably, the decline in spatial memory was less pronounced in rats exposed to EE (Table 1), highlighting the importance of early-life stimulation.

A critical question in this research was whether EE initiated in later life stages could still lead to significant cognitive improvements, implying CR induction. Our results suggest this is indeed possible, as there was minimal difference in performance between rats exposed to EE in childhood and those receiving EE only during aging. This finding underscores the effectiveness of late-life EE, supporting the hypothesis of CR formation even in aged brains, as EE appears to induce both structural [84, 85] and functional [86, 87] modifications, thus contributing to BR.

The effect size measures reinforce the role of EE in CR formation, whether started in childhood or during aging, suggesting immediate and sustained cognitive benefits.

In summary, these findings enhance our understanding of the importance of EE from childhood and even in later life stages for CR development. Despite the complexities of human aging, our results offer insights into potential preventive and intervention strategies to mitigate cognitive decline associated with normal and pathological aging.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study stems from the attrition inherent in longitudinal designs, which led to a reduction in the sample size due to mortality. Initially, 48 subjects were included, but only 32 remained by the study's end. This reduction posed challenges in conducting statistical comparisons using standard tests (e.g., Mann-Whitney Test, Student's t-Test). To address this, we employed multilevel linear modeling for data analysis. A potential solution to mitigate this limitation would involve using larger samples, accounting for an expected attrition rate of around 30% in longitudinal research.

It is also noteworthy that the literature presents various EE protocols. While some studies implement continuous EE exposure, others apply stimulation for limited periods each day [88-93]. This methodological variance, as Bennett et al. (2006) noted, complicates comparisons across studies. To refine future evaluations, incorporating groups exposed to EE continuously (24 hours) from childhood to old age, as well as groups with EE only at specific life stages, would be beneficial [94].

Conclusions

This study confirms that EE is an effective, non-pharmacological tool for exploring behavioral and neurobiological processes in animal models of lifespan, brain dysfunction, and injury. Our findings indicate that EE promotes CR and enhances spatial memory in Wistar rats, both when applied during childhood and later in life. These results support the notion that CR is not fixed but rather dynamic, continuing to develop across the lifespan. This implies that interventions started in later life stages can still enhance CR, potentially alleviating age-related cognitive decline.

Clinically, our findings underscore the value of integrating EE strategies in both early and later life stages to address cognitive decline linked to aging. Healthcare professionals might consider recommending EE-based programs ncluding physical, social, and cognitive activities as part of a holistic approach to managing or preventing dementia and promoting cognitive health. Furthermore, initiatives aimed at improving socioeconomic and educational opportunities may have broad implications for cognitive and brain health as individuals age. Sustained engagement in stimulating environments could help build and maintain CR, thereby reducing dementia’s impact and improving quality of life for aging populations.

It is essential, however, to acknowledge the study's limitations. Further research is needed to confirm these findings in humans and to explore the effectiveness of varied EE programs. Future studies should also examine the role of genetic factors and their interactions with life experiences in CR formation. In conclusion, our findings lay a strong foundation for incorporating EE strategies into clinical practice as a promising approach to combat age-related cognitive decline.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), grant nº 2013/16427-3.

References

- Uttl B, Graf P. Episodic spatial memory in adulthood. Psychology and Aging 8 (1993): 257.

- Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine 148 (2008): 427-434.

- Tóth-Fáber E, Nemeth D, Janacsek K. Lifespan developmental invariance in memory consolidation: Evidence from procedural memory. PNAS Nexus 2 (2023): pgad037.

- Wimmer ME, Hernandez PJ, Blackwell J, et al. Aging impairs hippocampus-dependent long-term memory for object location in mice. Neurobiology of Aging 33 (2012): 2220-2224.

- Yu L, Russ AN, Algamal M, et al. Slow wave activity disruptions and memory impairments in a mouse model of aging. Neurobiology of Aging 140 (2024): 12-21.

- Nyberg L, Pudas S. Successful memory aging. Annual Review of Psychology 70 (2019): 219-243.

- Boyle PA, Wang T, Yu L, et al. To what degree is late-life cognitive decline driven by age-related neuropathologies? Brain 144 (2021): 2166-2175.

- Schwarz C, Franz CE, Kremen WS, et al. Reserve, resilience, and maintenance of episodic memory and other cognitive functions in aging. Neurobiology of Aging 140 (2024): 60-69.

- Changeux JP, Danchin A. Selective stabilization of developing synapses as a mechanism for the specification of neuronal networks. Nature 264 (1976): 705-712.

- Villanueva-Castillo C, Tecuatl C, Herrera-López G, et al. Aging-related impairments of hippocampal mossy fibers synapses on CA3 pyramidal cells. Neurobiology of Aging 49 (2017): 119-137.

- Barnes CA, Suster MS, Shen J, et al. Multistability of cognitive maps in the hippocampus of old rats. Nature 388 (1997): 272-275.

- Jones S, Nyberg L, Sandblom J, et al. Cognitive and neural plasticity in aging: General and task-specific limitations. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 30 (2006): 864-871.

- Abe O, Aoki S, Hayashi N, et al. Normal aging in the central nervous system: Quantitative MR diffusion-tensor analysis. Neurobiology of Aging 23 (2002): 433-441.

- Schwarz CG, Gunter JL, Wiste HJ, et al. A large-scale comparison of cortical thickness and volume methods for measuring Alzheimer's disease severity. NeuroImage: Clinical 11 (2016): 802-812.

- Jung JH, Lee GW, Lee JH, et al. Multiparity, brain atrophy, and cognitive decline. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 12 (2020): 159.

- Bloss EB, Janssen WG, Ohm DT, et al. Evidence for reduced experience-dependent dendritic spine plasticity in the aging prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience 31 (2011): 7831-7839.

- Jobson DD, Hase Y, Clarkson AN, et al. The role of the medial prefrontal cortex in cognition, aging, and dementia. Brain Communications 3 (2021): fcab125.

- Gazzaley A, D’Esposito M. Top-down modulation and normal aging. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1097 (2007): 67-83.

- Liang JH, Yang L, Wu S, et al. Discovery of efficient stimulators for adult hippocampal neurogenesis based on scaffolds in dragon’s blood. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 136 (2017): 382-392.

- Terreros-Roncal J, Moreno-Jiménez EP, Flor-García M, et al. Impact of neurodegenerative diseases on human adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Science 374 (2021): 1106-1113.

- Lindenberger U. Human cognitive aging: Corriger la fortune? Science 346 (2014): 572-578.

- Schwarz C, Franz CE, Kremen WS, et al. Reserve, resilience, and maintenance of episodic memory and other cognitive functions in aging. Neurobiology of Aging 140 (2024): 60-69.

- Cabeza R, Albert M, Bansal R, et al. Brain activity and cognitive reserve in aging. Neurobiology of Aging 122 (2021): 8-17.

- Kremen WS, Beck A, Elman JA, et al. Influence of young adult cognitive ability and additional education on later-life cognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (2019): 2021-2026.

- Stern Y, Albert M, Barnes CA, et al. A framework for concepts of reserve and resilience in aging. Neurobiology of Aging 124 (2023): 100-103.

- Stern Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 8 (2002): 448-460.

- Kremen WS, Elman JA, Panizzon MS, et al. Cognitive reserve and related constructs: A unified framework across cognitive and brain dimensions of aging. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 14 (2022): 834765.

- Satz P, Cole MA, Hardy DJ, et al. Brain and cognitive reserve: Mediator(s) and construct validity, a critique. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 33 (2011): 121-130.

- Le Carret N, Auriacombe S, Letenneur L, et al. Influence of education on the pattern of cognitive deterioration in AD patients: The cognitive reserve hypothesis. Brain and Cognition 57 (2005): 120-126.

- Meng X, D’Arcy C. Education and dementia in the context of the cognitive reserve hypothesis: A systematic review with meta-analyses and qualitative analyses. PLOS ONE 7 (2012): e38268.

- Wilson RS, Yu L, Lamar M, et al. Education and cognitive reserve in old age. Neurology 92 (2019): e1041-e1050

- Stern Y, Barulli D. Cognitive reserve. Handbook of Clinical Neurology 167 (2019): 181-190.

- Vuoksimaa E, Panizzon MS, Chen CH, et al. Cognitive reserve moderates the association between hippocampal volume and episodic memory in middle age. Neuropsychologia 51 (2013): 1124-1131.

- Birch AM, Kelly AM. Lifelong environmental enrichment in the absence of exercise protects the brain from age-related cognitive decline. Neuropharmacology 145 (2019): 59-74.

- Diamond MC, Krech D, Rosenzweig MR. The effects of an enriched environment on the histology of the rat cerebral cortex. Journal of Comparative Neurology 123 (1964): 111-119.

- Rosenzweig MR. Aspects of the search for neural mechanisms of memory. Annual Review of Psychology 47 (1996): 1-32.

- Rosenzweig MR, Bennett EL. Psychobiology of plasticity: Effects of training and experience on brain and behavior. Behavioural Brain Research 78 (1996): 57-65.

- Gould E, Beylin A, Tanapat P, et al. Learning enhances adult neurogenesis in the hippocampal formation. Nature Neuroscience 2 (1999): 260-265.

- Williams BM, Luo Y, Ward C, et al. Environmental enrichment: Effects on spatial memory and hippocampal CREB immunoreactivity. Physiology & Behavior 73 (2001): 649-658.

- Gorantla VR, Thomas SE, Millis RM. Environmental enrichment and brain neuroplasticity in the kainate rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Journal of Epilepsy Research 9 (2019): 51-64.

- Melani R, Chelini G, Cenni MC, et al. Enriched environment effects on remote object recognition memory. Neuroscience 352 (2017): 296-305.

- Fuchs F, Cosquer B, Penazzi L, et al. Exposure to an enriched environment up to middle age allows preservation of spatial memory capabilities in old age. Behavioural Brain Research 299 (2016): 1-5.

- Mandolesi L, Gelfo F, Serra L, et al. Environmental factors promoting neural plasticity: Insights from animal and human studies. Neural Plasticity 2017 (2017): 7219461.

- Byrne P, Becker S, Burgess N. Remembering the past and imagining the future: A neural model of spatial memory and imagery. Psychological Review 114 (2007): 340-375.

- Klee LW, Hoover DM, Mitchell ME, et al. Long term effects of gastrocystoplasty in rats. The Journal of Urology 144 (1990): 1283-1287.

- Hayward BE, Zavanelli M, Furano AV. Recombination creates novel L1 (LINE-1) elements in Rattus norvegicus. Genetics 146 (1997): 641-654.

- Clough G. Environmental effects on animals used in biomedical research. Biological Reviews 57 (1982): 487-523.

- Ham WT, Mueller HA, Sliney DH. Retinal sensitivity to damage from short wavelength light. Nature 260 (1976): 153-155.

- Jacobs GH, Fenwick JA, Williams GA. Cone-based vision of rats for ultraviolet and visible lights. Journal of Experimental Biology 204 (2001): 2439-2446.

- Wielgus AR, Collier RJ, Martin E, et al. Blue light induced A2E oxidation in rat eyes–Experimental animal model of dry AMD. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences 9 (2010): 1505-1512.

- Sampedro-Piquero P, De Bartolo P, Petrosini L, et al. Astrocytic plasticity as a possible mediator of the cognitive improvements after environmental enrichment in aged rats. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 114 (2014): 16-25.

- Hullinger R, O’Riordan K, Burger C, et al. Environmental enrichment improves learning and memory and long-term potentiation in young adult rats through a mechanism requiring mGluR5 signaling and sustained activation of p70s6k. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 125 (2015): 126-134.

- Morris R G. Spatial localization does not require the presence of local cues. Learning and Motivation 12 (1982): 239-260.

- Morris R G, Garrud P, Rawlins J A, et al. Place navigation impaired in rats with hippocampal lesions. Nature 297 (1982): 681-683.

- Soares E, Francisco J I, Castanha R G, et al. Induced social isolation generates negative effects on the spatial memory of rats. International Journal of Psychology and Neuroscience 8 (2022): 90-106

- Barnhart C D, Yang D, Lein P J, et al. Using the Morris water maze to assess spatial learning and memory in weanling mice. PLOS ONE 10 (2015): e0124521.

- Andre P, Zaccaroni M, Fiorenzani P, et al. Offline consolidation of spatial memory: Do the cerebellar output circuits play a role? Brain Research 1718 (2019): 148-158.

- Othman M Z, Hassan Z, Has A T C, et al. Morris water maze: A versatile and pertinent tool for assessing spatial learning and memory. Experimental Animals 71 (2022): 264-280.

- Kreft I G, De Leeuw J. Introducing multilevel modeling. Sage Publications (1998).

- Gelman A, Hill J. Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge University Press (2007).

- Stan Development Team. Stan modeling language users guide and reference manual. Stan Development Team (2016).

- Gelman A, Carlin J, Stern H, et al. Bayesian data analysis. 3rd ed. Chapman and Hall/CRC (2013).

- Hedges L V. Distribution theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. Journal of Educational Statistics 6 (1981): 107-128.

- Hedges L V. Distribution theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. Journal of Educational Statistics 6 (1981): 107-128.

- Kelley K, Preacher K J, et al. On effect size. Psychological Methods 17 (2012): 137.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge (2013)

- Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology 4 (2013): 863.

- Gardner E B, Boitano J J, Mancino N S, et al. Environmental enrichment and deprivation: Effects on learning, memory, and exploration. Physiology & Behavior 14 (1975): 321-327.

- Petrosini L, De Bartolo P, Foti F, et al. On whether the environmental enrichment may provide cognitive and brain reserves. Brain Research Reviews 61 (2009): 221-239.

- Hosseiny S, Pietri M, Petit-Paitel A, et al. Differential neuronal plasticity in mouse hippocampus associated with various periods of enriched environment during postnatal development. Brain Structure and Function 220 (2015): 3435-3448.

- Ghiglieri V, Calabresi P, et al. Environmental enrichment repairs structural and functional plasticity in the hippocampus. In Neurobiological and Psychological Aspects of Brain Recovery (2017): 55-77.

- Melani R, Chelini G, Cenni M C, et al. Enriched environment effects on remote object recognition memory. Neuroscience 352 (2017): 296-305.

- Ohline S M, Abraham W C, et al. Environmental enrichment effects on synaptic and cellular physiology of hippocampal neurons. Neuropharmacology 145 (2019): 3-12.

- Barros W, David M, Souza A, et al. Can the effects of environmental enrichment modulate BDNF expression in hippocampal plasticity? A systematic review of animal studies. Synapse 73 (2019): e22103

- Lima A P, Silva K, Padovan C M, et al. Memory, learning, and participation of the cholinergic system in young rats exposed to environmental enrichment. Behavioural Brain Research 259 (2014): 247-252.

- Gelfo F, Mandolesi L, Serra L, et al. The neuroprotective effects of experience on cognitive functions: Evidence from animal studies on the neurobiological bases of brain reserve. Neuroscience 370 (2018): 218-235.

- Balietti M, Conti F, et al. Environmental enrichment and the aging brain: Is it time for standardization? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 139 (2022): 104728.

- Leal-Galicia P, Castañeda-Bueno M, Quiroz-Baez R, et al. Long-term exposure to environmental enrichment since youth prevents recognition memory decline and increases synaptic plasticity markers in aging. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 90 (2008): 511-518.

- Amaral O B, Vargas R S, Hansel G, et al. Duration of environmental enrichment influences the magnitude and persistence of its behavioral effects on mice. Physiology & Behavior 93 (2008): 388-394.

- Harland B C, Dalrymple-Alford J C, et al. Enriched environment procedures for rodents: Creating a standardized protocol for diverse enrichment to improve consistency across research studies. Bio-protocol 10 (2020): e3637.

- Nachtigall E G, de Freitas J D, Marcondes L A, et al. Memory persistence induced by environmental enrichment is dependent on different brain structures. Physiology & Behavior 272 (2023): 114375.

- Schoentgen B, Gagliardi G, Défontaines B, et al. Environmental and cognitive enrichment in childhood as protective factors in the adult and aging brain. Frontiers in Psychology 11 (2020): 1814.

- Landolfo E, Cutuli D, Decandia D, et al. Environmental enrichment protects against neurotoxic effects of lipopolysaccharide: A comprehensive overview. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24 (2023): 5404.

- Darmopil S, Petanjek Z, Mohammed A H, et al. Environmental enrichment alters dentate granule cell morphology in oldest-old rat. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 13 (2009): 1845-1856

- Sampedro-Piquero P, De Bartolo P, Petrosini L, et al. Astrocytic plasticity as a possible mediator of the cognitive improvements after environmental enrichment in aged rats. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 114 (2014): 16-25.

- Mora F, Segovia G, del Arco A, et al. Aging, plasticity and environmental enrichment: Structural changes and neurotransmitter dynamics in several areas of the brain. Brain Research Reviews 55 (2007): 78-88.

- Bayat M, Kohlmeier K A, Haghani M, et al. Co-treatment of vitamin D supplementation with enriched environment improves synaptic plasticity and spatial learning and memory in aged rats. Psychopharmacology 238 (2021): 2297-2312.

- Rampon C, Jiang C H, Dong H, et al. Effects of environmental enrichment on gene expression in the brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97 (2000): 12880-12884.

- Rampon C, Tang Y P, Goodhouse J, et al. Enrichment induces structural changes and recovery from nonspatial memory deficits in CA1 NMDAR1-knockout mice. Nature Neuroscience 3 (2000): 238-244.

- Frick K M, Fernandez S M, et al. Enrichment enhances spatial memory and increases synaptophysin levels in aged female mice. Neurobiology of Aging 24 (2003): 615-626.

- Gobbo O L, O'Mara S M, et al. Impact of enriched-environment housing on brain-derived neurotrophic factor and on cognitive performance after a transient global ischemia. Behavioural Brain Research 152 (2004): 231-241.

- Ratuski A S, Weary D M, et al. Environmental enrichment for rats and mice housed in laboratories: A metareview. Animals 12 (2022): 414.

- Sztainberg Y, Chen A, et al. An environmental enrichment model for mice. Nature Protocols 5 (2010): 1535-1539.

- Bennett J C, McRae P A, Levy L J, et al. Long-term continuous, but not daily, environmental enrichment reduces spatial memory decline in aged male mice. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 85 (2006): 139-152.

Appendix 1

Estimates based on the mean of the posterior distribution and a 95% credibility interval based on the quantiles of the posterior distribution for each group of subjects.

|

Phase |

Comparison |

IC 95% Inf |

Mean |

IC 95% Sup |

|

1 |

G2 - G1 | P=1, T=1 |

-1.400777 |

-1.069492 |

-0.739005 |

|

1 |

G2 - G1 | P=1, T=2 |

-1.676741 |

-1.339999 |

-1.0124711 |

|

1 |

P1T2 - P1T1 | G=1 |

-0.207274 |

0.003066 |

0.2159425 |

|

1 |

P1T2 - P1T1 | G=2 |

-0.479415 |

-0.267441 |

-0.055337 |

|

2 |

G2 - G1 | P=2, T=1 |

-1.969457 |

-1.578511 |

-1.1947878 |

|

2 |

G3 - G1 | P=2, T=1 |

-0.788166 |

-0.38474 |

0.0265792 |

|

2 |

G4 - G1 | P=2, T=1 |

-1.939014 |

-1.529838 |

-1.1334137 |

|

2 |

G3 - G2 | P=2, T=1 |

0.8014725 |

1.1937712 |

1.581441 |

|

2 |

G4 - G2 | P=2, T=1 |

-0.337515 |

0.048673 |

0.437758 |

|

2 |

G4 - G3 | P=2, T=1 |

-1.558635 |

-1.145098 |

-0.7359739 |

|

2 |

P2T1 - (0.5P1T1 + 0.5P1T2) | G=1 |

0.5394366 |

0.7759713 |

1.0096194 |

|

2 |

P2T1 - (0.5P1T1 + 0.5P1T2) | G=2 |

0.1955616 |

0.4022057 |

0.60925 |

|

2 |

G2 - G1 | P=2, T=2 |

-1.519303 |

-1.144092 |

-0.7613333 |

|

2 |

G3 - G1 | P=2, T=2 |

-0.214113 |

0.2314223 |

0.6868119 |

|

2 |

G4 - G1 | P=2, T=2 |

-1.187993 |

-0.734905 |

-0.2917532 |

|

2 |

G3 - G2 | P=2, T=2 |

0.9403847 |

1.3755148 |

1.8042776 |

|

2 |

G4 - G2 | P=2, T=2 |

-0.027228 |

0.4091878 |

0.8386313 |

|

2 |

G4 - G3 | P=2, T=2 |

-1.377703 |

-0.966327 |

-0.5592461 |

|

2 |

(0.5P2T1 + 0.5P2T2) - (0.5P1T1 + 0.5P1T2) | G=1 |

0.1956745 |

0.3892727 |

0.5776764 |

|

2 |

(0.5P2T1 + 0.5P2T2) - (0.5P1T1 + 0.5P1T2) | G=2 |

0.0658728 |

0.2327163 |

0.4018875 |

|

2 |

P2T2 - P2T1 | G=1 |

-1.04754 |

-0.773397 |

-0.4977958 |

|

2 |

P2T2 - P2T1 | G=2 |

-0.581542 |

-0.338979 |

-0.0990803 |

|

2 |

P2T2 - P2T1 | G=3 |

-0.494075 |

-0.157235 |

0.1822271 |

|

2 |

P2T2 - P2T1 | G=4 |

-0.30832 |

0.0215361 |

0.3522123 |

|

2 |

(G4 - G3) - (G2 - G1) | T=1 |

-0.611153 |

-0.075606 |

0.4490985 |

|

2 |

(G4 - G3) - (G2 - G1) | T=2 |

-0.162074 |

0.3736716 |

0.907535 |