Cerebellar Apoptotic Parameters and Circulating MiRNAs in Senile UChB Rats (Voluntary Ethanol Consumers)

Article Information

Martinez M1 # , Rossetto I. M. U4 # , Lizarte F. S. N2 # , Tirapelli L. F2 # , Tirapelli D. P. C2 # , Fioravante V. C 3 # , Chuffa L. G. A3, Martinez F. E 3*

1 Department of Morphology e Pathology, Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), São Carlos, SP, Brazil.

2 Department of Surgery and Anatomy, University of São Paulo (USP), Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil.

3 Department of Structural and Functional Biology, State University of São Paulo (UNESP), Botucatu, SP, Brazil.

4 Department of Structural and Functional Biology, University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Campinas, SP, Brazil.

#These authors contributed equally to this work

*Corresponding Author: Francisco Eduardo Martinez, Department of Structural and Functional Biology, State University of São Paulo (UNESP), Botucatu, SP, Brazil.

Received: 02 December 2025; Accepted: 04 December 2025; Published: 17 December 2025

Citation:

Martinez M, Rossetto I. M. U, Lizarte F. S. N, Tirapelli L. F, Tirapelli D. P. C, Fioravante V. C, Chuffa L. G. A, Martinez F. E. Cerebellar Apoptotic Parameters and Circulating MiRNAs in Senile UChB Rats (Voluntary Ethanol Consumers). Archives of Veterinary Science and Medicine. 8 (2025): 85-92.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Despite the lack of scientific data on the real impact of alcohol consumption in the elderly, excessive drinking is relatively common in this population. Aging is accompanied by reduced water content, diminished hepatic metabolic capacity, and altered brain responsiveness, making older individuals more vulnerable to alcohol-induced neurotoxicity. The cerebellum is particularly sensitive to ethanol, with documented impairments in motor coordination, balance, and cognitive functions. However, the effects of chronic ethanol exposure during senescence remain poorly understood. This study investigated apoptotic and anti-apoptotic signaling in the aged cerebellum of UChB rats, a strain characterized by voluntary ethanol consumption, and evaluated the expression of circulating microRNAs associated with apoptotic pathways. Immunohistochemistry and gene expression analyses revealed no

significant changes in cerebellar caspase-3, XIAP, or IGFR1 expression between ethanol-consuming and control aged rats, although minor differences in protein immunolocalization were observed. Conversely, serum levels of miR-9-3p, miR-15b-5p, miR-16-5p, miR-21, miR-200a, and miR-222-3p were significantly upregulated in the ethanol group. Taken together, the findings suggest that senile UChB rats develop a tolerance to chronic ethanol intake, preventing further activation of apoptotic cascades in the cerebellum. Additionally, the modulation of specific circulating miRNAs indicates a potential regulatory or compensatory role in this adaptive response. These miRNAs may serve as molecular indicators of ethanol exposure in aging and contribute to understanding mechanisms of neurobiological tolerance.

Keywords

Ethanol; Aging; Cerebellum; Tolerance; Apoptosis; MicroRNAs; UChB rats

Ethanol articles; Aging articles; Cerebellum articles; Tolerance articles; Apoptosis articles; MicroRNAs articles; UChB rats articles

Article Details

1. Introduction

Aging is associated with profound alterations in brain structure and function, including cognitive decline and increased vulnerability to neurotoxic insults [1]. Elderly individuals are particularly susceptible to the harmful effects of alcohol consumption due to age-related physiological changes, such as reduced total body water, diminished hepatic metabolic efficiency, and altered neuropharmacological responses [2]. Alcoholism is a multifactorial disease with a broad genetic impairment background. Alcohol-related disorders are defined by several criteria which can be dissected further at the genetic level [3]. Genetic factors contribute significantly to alcohol-seeking behavior and the abuse of its consumption, with the risk for diagnosis of alcoholism being approximately 50% from the genetic origin and 50% from the environmental conditions [4]. Ethanol metabolism is intimately linked with the physiological and behavioral aspects of ethanol consumption [5]. The cerebellum is one of the brain regions most consistently affected by ethanol exposure. Chronic or acute ethanol insults impair motor coordination, disrupt cerebellar circuitry, and contribute to neurodegeneration [6]. Ethanol-induced cerebellar damage has been documented in chronic alcoholics and in cases of prenatal exposure [7,8]. However, its specific impact during senescence remains poorly characterized. Genetic predisposition plays a fundamental role in alcohol-seeking behavior and susceptibility to ethanol-induced damage. UChB rats, selectively bred for high voluntary alcohol intake, possess metabolic and genetic features that influence their behavioral and neurobiological responses to ethanol [9,4,10,11]. ALDH2 allelic variants relevant to ethanol metabolism have been described in these strains, contributing to differential vulnerability [12,13]. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are key post-transcriptional regulators involved in apoptosis, neuroplasticity, and responses to neurotoxic stimuli. Ethanol-sensitive miRNAs have been implicated in addiction, neuroinflammation, and neuronal survival [14,15,16]. Their evaluation in aging models may reveal biomarkers and regulatory mechanisms underlying chronic ethanol exposure. This study aimed to investigate apoptotic signaling and miRNA expression in the cerebellum and serum of senile UChB rats subjected to chronic ethanol intake. By integrating molecular, histological, and circulating biomarkers, we sought to clarify whether aging modifies ethanol-induced neurotoxicity or promotes tolerance mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

30 senile male UChB rats, with 13 months of age, were obtained from the Department of Anatomy, Institute of Biosciences, UNESP - Campus of Botucatu, SP. Two experimental groups were formed (n = 15 animals): Ethanol group (EtOH-UChB): composed of UChB rats with voluntary consumption of 10 % ethanol solution (the average of ethanol consumption in this group was 7 g ethanol per kg of body weight / day) and Control group (Ctrl-UChB): composed of UChB rats deprived of 10 % ethanol solution, with a voluntary consumption of water only.

2.2. Selection of ethanol drinking animals and experimental procedures

The rats were initially subjected to the selection for ethanol intake followed by standardization of the UChB variety in accordance with the protocol by Mardones & Segovia-Riquelme (1983) outlined by Martinez et al. (2018). The experimental period started at 80th day, when 15 male UChB rats were housed in individual boxes, with solid floor and shavings, under controlled conditions of luminosity (12 h of darkness and 12 h of lightness) and temperature (20 - 25 ºC). During this period, the animals received food, water ad libitum and ethanol solution (1:10 v/v). At the end of the selection period for ethanol consumption until euthanasia (80 to 390 days-old), ethanol consumption was measured every 7 days. The animals of the EtOH-UChB group remained 325 consecutive days with a voluntary intake of 10 % ethanol solution. The experimental protocol followed the ethical principles of the National Council for the Control of Animal Experimentation (Brazil) and the Committee on Ethics in the Use of Animals (CEUA) from UFSCar. The study was conducted in accordance with the Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology policy for experimental and clinical studies (Tveden-Nyborg et al. 2023).

2.3. Gene expression in aged cerebellum

250 μL of PBS and 750 μL of Trizol® (Invitrogen, EUA) were added to each frozen sample (cerebellum samples from five animals per group were used). The samples were homogenized using Politron®. After the permanence at room temperature for 5 min, 200 μL of chloroform was added and mixed vigorously for 15 seconds. The final solution was centrifuged for 15 min (4 °C and 13.200 rpm) and the aqueous phase of the flasks was transferred to new tubes. The RNA was precipitated using 500 μL of isopropyl alcohol during 12 h at -20 ºC. Then, the solution was centrifuged again (20 min at 4 °C, 13.200 rpm), and the supernatant was discarded. 1000 μl of ethanol at 75 % was added and newly centrifuged for 5 min (13.200 rpm). The superior phase was discarded, and the dry pellet was dissolved in water treated with diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC) for 15 minutes. This material was aliquoted and stored at - 80 °C. The samples were submitted to electrophoresis in agarose gel at 1 % to RNA and the verification of the RNA integrity. For the cDNA synthesis, the reverse transcription was performed using the commercial kit (Applied Biosystems), High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each 1μg of RNA was added 2.5 μl of Reverse Transcriptase Buffer, followed by 1 μl of dNTPs, 2.5 μl of Random Primers, and 1.25 μl of the MultiScribeTM enzyme, completing the volume with DEPC water to 20 μl. The differential expression of caspase-3 (Assay ID Rn00563902_m1), XIAP (Assay Rn01457299_m1), and IGFR1 (Rn00583837_m1) were quantified. The β-actin gene was used as endogenous control. The cDNA was obtained from the samples, and amplification was performed through quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR-RT) in real-time using TaqMan Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). For the quantitative analysis of gene expressions, we used the commercially available system TaqMan Assay-on-demand, composed of oligonucleotides and probes (Applied Biosystems). A gadget of PCR detection in real-time 7500 PCR System (Applied Biosystems) was used with the software Sequence Detection System for obtaining the CT values. The reactions were performed in duplicates using TaqMan Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, EUA). The amplification was performed in a final volume of 10 μl, using 5 μl of the specific reagent TaqMan Master Mix, 0.5 μl of each specific probe, and 4.5 μl of cDNA diluted in 1:10. The data were exported to Excel spreadsheets to calculate ΔCT. The standard conditions for the amplification were 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C during 1 min (simultaneous annealing and extension).

2.4. Real-time PCR for miRNA expression

Animals were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of 90 mg/kg ketamine chloride (Ketalar/ laboratory: Parke-Davis) and 10 mg/kg of xylazine (Rompum/ laboratory: Bayer). Later, 1 mL of blood from rats’ lateral tail veins was collected and processed for RNA extraction. The expression profiles of the miRNAs -9-3p (Assay ID: 002231), -15b-5p (Assay ID: 000390), -16-5p (Assay ID: 000391), -21-5p (Assay ID: 000397), -200a-3p (Assay ID: 000502) and -222-3p (Assay ID: 002276) were analyzed using the whole blood of each animal. Total cellular RNA was extracted using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and RNA was reverse transcribed to single-stranded cDNA, using a High-Capacity Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) with specific primers provided by the TaqMan microRNAs assays according to the manufacturer's protocol. For quantitative analysis of the miRNAs -9-3p, -15b-5p, -16-5p, -21-5p, -200a-3p, and -222-3p, we used the commercially available system TaqMan Assay-on demand (Applied Biosystems). Reverse transcription was performed using 5 ng of RNA for each sample in 7.5 µL of the total reaction mixture. The cDNA obtained was diluted 1:4 and 4.5 µL was used for each 10 µL of the quantitative real-time PCR reaction mixture using the TaqMan Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). All reactions were carried out duplicate and analyzed with the 7500 Sequence Detection System apparatus (Applied Biosystems). Data was analyzed using the ABI-7500 SDS software. The total RNA absorbed was normalized based on the Ct value for U6 (000391). The variation in expression levels was calculated by the 2-ΔΔCt method, with the mean ΔCt value for a group of miRNAs -9-3p, -15b-5p, -16-5p, -21-5p, -200a-3p and -222-3p. Samples from control animals were used as a calibrator. For these miRNAs, the expression evaluation and statistical analysis were performed using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test and One-way ANOVA. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05. Graphical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 go Windows, (GraphPad Software, San Diego - California USA).

2.5. Immunostaining for caspase-3, XIAP and IGFR1

5 μm thick sections were obtained using the microtome (Biocut - Model 1130) and collected on silanized slides. Antigen retrieval was performed by incubating the tissue sections in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 100 °C in microwave or treatment with proteinase K, depending on the antibody. Endogenous peroxidase blockade was performed with H2O2 (0.3 % diluted in methanol) and posterior incubation in BSA solution (3 %) diluted in TBS-T buffer for 1 h. The membranes were immunoreacted with antibodies for caspase-3, XIAP and IGFR1 diluted in 1 % BSA (1:35-200) and stored overnight at 4 ºC. The Envision HRP kit (Dako Cytomation Inc., EUA) was used for antigen detection, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The staining was revealed using diaminobenzidine (DAB), followed by counter-staining with Harris’ Hematoxylin.

2.6. Morphometric parameters of immunohistochemical reactions

For immunohistochemical analysis of caspase-3, XIAP, and IGFR1, ten fields were randomly selected in each slide based on the magnification of 40 x animal /group in the cerebellar cortex. Purkinje cells, Bergmann glia, and granule neurons were particularly observed. The white matter cells were counted as a whole, excluding just the neurons of the cerebellar nuclei. The number of reactive cells was measured, and the relative frequency of staining was calculated for each cellular type. For XIAP and IGFR1, the analysis qualitatively considers difference in intensity of staining, location, or distribution between the groups ).

2.7. Statistical analysis

All data were exported to Excel and transferred to GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Prism, Inc, San Diego, CA, USA). The results obtained for each parameter were considered parametric within the group and analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk normal distribution test. Student’s t-test was used for comparison. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

Caspase-3, XIAP, and IGFR1 are differentially modulated in the aged cerebellum following chronic ethanol consumption.

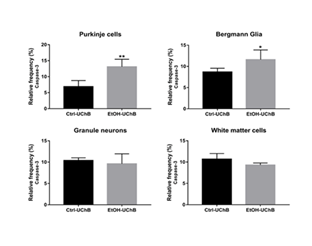

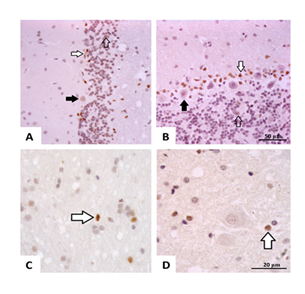

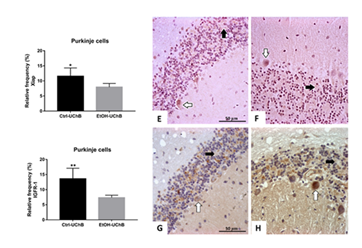

Chronic ethanol intake increased the relative frequency of caspase-3–positive Purkinje cells and Bergmann glia in aged rats (Figure 1 and 2 A, B). In contrast, granule neurons and white matter cells showed comparable caspase-3 levels between the Control and Ethanol groups (Figure 1 and 2 C, D). XIAP immunostaining was reduced in Purkinje cells of the Ethanol group, while Bergmann glia and granule neurons exhibited diffuse labeling, particularly within the glomerular layer (Figure 3 E, F). Similarly, IGFR1 immunolocalization decreased in the Ethanol group, with scattered labeling in Bergmann glia and granule neurons, especially in the glomerular zone (Figure 3 G, H).

Figure 2: Photomicrographs of the cerebellum from Ctrl-UChB (A, C) and EtOH-UchB (B, D) groups. Representative images show positive labeling for Caspase-3 in the Purkinje cell layer (black arrow), for Bergmann Glia (white arrow), and the granular layer (unfilled arrow) (A, B). 400X. Positive reactivity for Caspase-3 in the White matter cells. (C, D) 1000X.

Figure 3: Mean (± standard deviation) of immunoreactivity for XIAP and IGFR1 in Purkinje cells of the cerebellum. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. Representative images show positive immunoreactivity for XIAP (E, F) and IGFR1 (G, H) in Purkinje cells (white arrows) and scattered staining in the glomerular zone (black arrows). E, G: Ctrl-UchB group; F, H: EtOH-UchB group 400X.

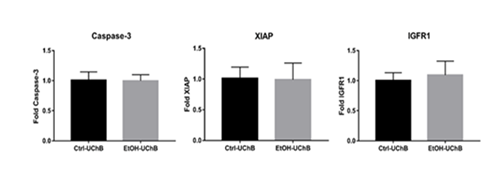

3.1. Gene expression remains unchanged despite chronic ethanol exposure

Despite differences in protein localization, no statistically significant changes were detected in mRNA expression levels of caspase-3, XIAP, or IGFR1 between the groups (Figure 4).

3.2. Chronic ethanol consumption alters circulating apoptotic-related miRNAs in aged rats

Serum expression of miR-9-3p, miR-15b-5p, miR-16-5p, miR-21, miR-200a, and miR-222-3p were significantly upregulated in the Ethanol group, indicating systemic modulation of apoptosis-related regulatory gateways (Figure 5).

4. Discussion

Chronic ethanol consumption did not induce significant morphological or molecular alterations in the cerebellum of aged UChB rats, suggesting a state of functional tolerance that blunted the expected neurodegenerative effects. Although ethanol neurotoxicity is well documented [17,18,]. The absence of major alterations in apoptotic markers supports the idea that long-term ethanol exposure interacts with the genetic and metabolic background of UChB rats [12] shaping their neural response to chronic intake. Genetic predisposition plays a central role in alcohol dependence and the neurobiological consequences of ethanol exposure [19]. UChB rats carry ALDH2 alleles with high affinity for NAD+ [20,12]. facilitating efficient acetaldehyde metabolism and contributing to higher voluntary alcohol intake. This metabolic advantage is also associated with the rapid development of acute tolerance, particularly to ethanol-induced motor impairment [21]. The molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying tolerance including adaptations in ion channels, intracellular signaling, and neuron glia communication are known to shape behavioral responses to ethanol [22, 23,24]. In line with these mechanisms, the present study found no significant changes in caspase-3, XIAP, or IGFR1 expression, reinforcing the notion of neuroadaptation rather than neurodegeneration in aged UChB rats. Comparisons with previous studies further support this interpretation. Both Oliveira et al [25] and Martinez et al [11] reported robust apoptotic activation in adult UChA and UChB rats exposed to ethanol. However, the current aged animals showed remarkably lower levels of caspase-3 and XIAP, suggesting that senescence-related cerebellar decline may overshadow or mask additional ethanol-induced damage. Aging alone is associated with reduced cerebellar volume, neuronal loss, and apoptosis [26,27] and when combined with ethanol exposure, may shift the brain’s response from degeneration toward adaptive molecular restraint, possibly mediated by reduced apoptotic competence. Regarding IGFR1, no significant differences were detected, contrasting with studies showing ethanol inhibition of IGF-mediated survival pathways in developing or adolescent brains [28-31]. Ethanol has been shown to reduce IGF production and impair PI3-kinase signaling, leading to neuronal loss and cerebellar hypoplasia during development. However, these effects are less pronounced in senile animals, who may already exhibit blunted growth-factor signaling as part of physiological aging. Thus, chronic ethanol consumption in aged UChB rats likely fails to further suppress IGF signaling beyond the age-related baseline. The role of miRNA-mediated neuroadaptation is an important consideration when interpreting the mild cerebellar response. Ethanol-sensitive miRNAs act as molecular switches regulating plasticity, tolerance, and addiction and early-life environmental exposures can produce lasting changes in neurobehavior [32,33]. Chronic ethanol exposure and withdrawal are known triggers of long-lasting molecular adaptations in mesocorticolimbic circuits [34-36]. These adaptations include adjustments in apoptotic pathways such as the reduction of ethanol-induced toxicity observed by Johansson et al. [37] which may contribute to the attenuated apoptotic profile found in this study. Moreover, shifts in miRNA expression during chronic alcohol exposure may confer compensatory protection against neurodegeneration and support behavioral tolerance [38,39]. Evidence from adolescent models indicates that ethanol-induced changes in mGlu2 receptor signaling alter striatal circuitry and influence tolerance development [40,41], further emphasizing the complexity of these adaptive responses. Taken together, the lack of apoptotic activation in the cerebellum of aged UChB rats aligns with a broader framework in which genetic predisposition, metabolic efficiency, age-related decline, and miRNA-regulated neuroadaptations interact to shape the neural impact of chronic ethanol exposure. Although this study used only male rats, potentially limiting generalizability, the findings highlight the resilience and compensatory capacity of the UChB strain. They also underscore the importance of considering age and genetic background when evaluating ethanol’s neurobiological effects. Finally, the involvement of miRNAs and other regulatory molecules points to promising avenues for future research, particularly in identifying biomarkers or therapeutic targets that differentiate susceptibility to ethanol-induced cerebellar damage across genetically distinct populations [42].

5. Conclusions

Our findings reveal that aged UChB rats maintain cerebellar apoptotic stability despite lifelong voluntary ethanol intake, supporting the notion that senescence combined with genetic predisposition shapes a state of functional tolerance to ethanol neurotoxicity in apoptotic parameters. While apoptotic markers remain unchanged at the transcriptional level, the pronounced elevation of circulating miRNAs involved in apoptotic regulation suggests a systemic compensatory mechanism rather than local tissue damage. These results underscore the importance of considering age, genetic background, and metabolic characteristics when evaluating ethanol-induced neurobiological alterations and identify specific miRNAs as promising candidates for biomarkers of chronic alcohol exposure in aging populations.

6. Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, Grants # 2013/13604-1 and 2015/07807-2).

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Wanderley Thiago da Silva for animal care and Mr. Gelson Rodrigues for technical support.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study's findings are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- La Sala G, Farini D. Glial Cells and Aging: From the CNS to the Cerebellum. Int J Mol Sci 26 (2025): 7553.

- Van Gils Y, Franck E, Dierckx E, et al. The Role of Psychological Distress in the Relationship between Drinking Motives and Hazardous Drinking in Older Adults. Eur Addict Res 27 (2021): 33-41.

- Sanchez-Roige S, Palmer AA, Clarke TK. Recent Efforts to Dissect the Genetic Basis of Alcohol Use and Abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87: 609-618.

- Dick DM, Bierut LJ. The genetics of alcohol dependence. Curr Psychiatry Rep 8 (2006): 151-157.

- Mackowiak B, Haggerty DL, Lehner T, et al. Peripheral alcohol metabolism dictates ethanol consumption and drinking microstructure in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res (Hoboken) 49 (2025): 970-984.

- Mitoma H, Manto M, Shaikh AG. Mechanisms of Ethanol-Induced Cerebellar Ataxia: Underpinnings of Neuronal Death in the Cerebellum. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18 (2021): 8678.

- Sullivan EV, Deshmukh A, Desmond JE, et al. Cerebellar volume decline in normal aging, alcoholism, and Korsakoff's syndrome: relation to ataxia. Neuropsychology 14 (2000): 341-352.

- Syaifullah AH, Shiino A, Fujiyoshi A, et al. SESSA Research Group. Alcohol Drinking and Brain Morphometry in Apparently Healthy Community-Dwelling Japanese Men. Alcohol 2 (2020): S0741-8329.

- Mardones J, Segovia-Riquelme N. Thirty-two years of selection of rats by ethanol preference: UChA and UChB strains. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol 5 (1983): 171-178.

- Enoch, MA. Genetic Influences on the Development of Alcoholism. Current Psychiatry Reports15 (2013): 4-12.

- Martinez M, Rossetto IMU, Neto FSL, et al. Interactions of ethanol and caffeine on apoptosis in the rat cerebellum (voluntary ethanol consumers). Cell Biol Int 42 (2018): 1575-1583.

- Quintanilla ME; Israel Y; Sapag A; et al. The UChA and UChB rat lines: metabolic and genetic differences influencing ethanol intake. Addict Biol 11 (2006): 310-323.

- Hendershot CS, Wardell JD, McPhee MD, et al. A prospective study of genetic factors, human laboratory phenotypes, and heavy drinking in late adolescence. Addict Biol 22 (2017): 1343-1354.

- Novais PC. Análise dos microRNAs:15,16,21,221 e 222 como marcadores moleculares no sangue de ratos submetidos à isquemia cerebral focal associada ou não ao alcoolismo. 2012, 97p, USP, Ribeirão Preto.

- Ibáñez F, Ureña-Peralta JR, Costa-Alba P, et al. Circulating MicroRNAs in Extracellular Vesicles as Potential Biomarkers of Alcohol-Induced Neuroinflammation in Adolescence: Gender Differences. Int J Mol Sci 21 (2020): 6730.

- Wang X, He Y, Mackowiak B, et al. MicroRNAs as regulators, biomarkers and therapeutic targets in liver diseases. Gut 70 (2021): 784-795

- Heimfarth L, Loureiro SO, Dutra MF, et al. Disrupted cytoskeletal homeostasis, astrogliosis and apoptotic cell death in the cerebellum of preweaning rats injected with diphenyl ditelluride. Neurotoxicology 34 (2013): 175-88.

- De La Monte SM, Krill JJ. Human alcohol-related neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol 127 (2014): 71-90.

- Korpi, ER.; Den Hollander, B, et al. Mechanisms of Action and Persistent Neuroplasticity by Drugs of Abuse. Pharmacol Rev 67 (2015): 872-1004.

- Sapag A, Tampier L, Valle-Prieto A, et al. Mutations in mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) change cofactor affinity and segregate with voluntary alcohol consumption in rats. Pharmacogenetics 13 (2003): 509-515.

- Tampier L, Quintanilla ME. Involvement of brain ethanol metabolism on acute tolerance development and on ethanol consumption in alcohol-drinker (UChB) and non-drinker (UChA) rats. Addict Biol 8 (2003): 279-286.

- Crabbe JC, Rigter H, Uijlen J, et al. Rapid development of tolerance to the hypothermic effect of ethanol in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 208 (1979): 128-133

- Pietrzykowski AZ; Treistmen SN. The Molecular Basis of Tolerance. Alcohol Research & Health 31 (2008).

- Ayers-Ringler JR, Jia YF, Qiu YY, et al. Role of astrocytic glutamate transporter in alcohol use disorder. World J Psychiatry 6 (2016): 31-42

- Oliveira SA, Chuffa LG, Fioruci-Fontanelli BA, et al. Apoptosis of Purkinje and granular cells of the cerebellum following chronic ethanol intake. Cerebellum 13 (2016): 728-738.

- Dorszewska J, Adamczewska-Goncerzewicz, Z, Szczech J. Apoptotic proteins in the course of aging of central nervous. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology 139 (2004): 145-155.

- Dlugos, CA. Ethanol-Induced Alterations in Purkinje Neuron Dendrites in Adult and Aging Rats: a Review. Cerebellum 14 (2015): 466-473.

- Zhang FX, Rubin R, Rooney TA. Ethanol induces apoptosis in cerebellar granule neurons by inhibiting insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling. J Neurochem 71 (1998): 196-204.

- Cassini C, Linden R. Exposição pré-natal ao etanol: toxicidade, biomarcadores e métodos de detecção. Prenatal exposure to ethanol: toxicity, biomarkers and detection methods. Rev Psiq Clín 38 (2011): 116-121.

- Ewenczyk A, Ziplow J, Tong M, et al. Sustained Impairments in Brain Insulin/IGF Signaling in Adolescent Rats Subjected to Binge Alcohol Exposures during Development. J Clin Exp Pathol 2 (2012): 106.

- Ni Q, Tan Y, Zhang X, et al. Prenatal ethanol exposure increases osteoarthritis susceptibility in female rat offspring by programming a low-functioning IGF-1 signaling pathway. Sci Rep 5 (2015): 14711.

- Sathyan Pratheesh, Honey B. Golden, and Rajesh C. Miranda. Competing Interactions between Micro-RNAs Determine Neural Progenitor Survival and Proliferation after Ethanol Exposure: Evidence from an Ex Vivo Model of the Fetal Cerebral Cortical Neuroepithelium. J Neurosci 27 (2007): 8546-8557.

- Korosi A, Naninck EF, Oomen CA, et al. Early-life stress mediated modulation of adult neurogenesis and behavior. Behav Brain Res 227 (2012): 400-409.

- Flatscher-Bader T, Van der Brug M, Hwang JW, et al. Alcohol-responsive genes in the frontal cortex and nucleus accumbens of human alcoholics. Journal of Neurochemistry 93 (2005): 359-370.

- Guo Y, Chen Y, Stephanie C, et al. Chronic Intermittent Ethanol Exposure and Its Removal Induce a Different miRNA Expression pattern in Primary Cortical Neuronal Cultures. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36 (2012): 1058-1066.

- Pati D, Marcinkiewcz CA, DiBerto JF, et al. Chronic intermittent ethanol exposure dysregulates a GABAergic microcircuit in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Neuropharmacology 168 (2020): 107-759.

- Johansson S, Ekström TJ, Marinova Z, et al. Dysregulation of cell death machinery in the prefrontal cortex of human alcoholics. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 12 (2009): 109-115.

- Farris SP, Miles MF. Ethanol modulation of gene networks: implications for alcoholism. Neurobiol Dis 45 (2012):115-121.

- Gorini G, Nunez YO, Mayfield RD. Integration of miRNA and Protein Profiling Reveals Coordinated Neuroadaptations in the Alcohol-Dependent Mouse Brain. PLoS One 8 (2013): e82565.

- Abburi C, Wolfman SL, Metz RA, et al. Tolerance to Ethanol or Nicotine Results in Increased Ethanol Self-Administration and Long-Term Depression in the Dorsolateral Striatum. eNeuro 3 (2016): 112-115.

- Johnson KA, Liput DJ, Homanics GE, et al. Age-dependent impairment of metabotropic glutamate receptor 2-dependent long-term depression in the mouse striatum by chronic ethanol exposure. Alcohol 82 (2020): 11-21.

- Ricarte Filho JCM, Kimura ET. MicroRNAs: novel class of gene regulators involved in endocrine function and cancer. R. Bras Endocrinol Metab 50 (2006): 1102-1107