Artificial Intelligence in Anesthesia, Critical Care, and Beyond: Current Applications, Future Prospects, and Limitations

Article Information

Michiaki Yamakage, MD, PhD1*, Soshi Iwasaki, MD, PhD1, Atsushi Sawada, MD, PhD1, Tomohiro Chaki, MD, PhD1, Ken-Ichiro Kikuchi, MD, PhD2, Yusuke Iwamoto, MD, PhD3

1Department of Anesthesiology, Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, South 1, West 16, 291, Chuo-ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan

2Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, South 1, West 16, 291, Chuo-ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan

3Department of Emergency Medicine, Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine South 1, West 16, 291, Chuo-ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan

*Corresponding Author: Michiaki Yamakage, Department of Anesthesiology, Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, South 1, West 16, 291, Chuo-ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan.

Received: 22 January 2026; Accepted: 29 January 2026; Published: 05 February 2026

Citation: Michiaki Yamakage, Soshi Iwasaki, Atsushi Sawada, Tomohiro Chaki, Ken-Ichiro Kikuchi, Yusuke Iwamoto. Artificial Intelligence in Anesthesia, Critical Care, and Beyond: Current Applications, Future Prospects, and Limitations. Anesthesia and Critical Care. 8 (2026): 06-24.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

The Artificial intelligence (AI) represents a paradigm shift in healthcare delivery, particularly in data-intensive, time-sensitive clinical specialties. Anesthesiology, intensive care medicine, and emergency medicine stand at the forefront of this technological transformation due to their reliance on continuous physiological monitoring, rapid decision-making, and complex data interpretation. Beyond acute care specialties, emerging applications extend to palliative care, pain management, and traditional East Asian medicine, demonstrating AI's versatility across diverse clinical contexts. This comprehensive narrative review synthesizes recent literature on AI applications across these specialties, providing a balanced assessment of current achievements, persistent limitations, and future research priorities. AI has demonstrated significant promise across multiple clinical domains, with applications including real-time anesthetic depth monitoring, predictive models for postoperative complications, ICU early warning systems, sepsis prediction algorithms, emergency department triage optimization, palliative care referral support, personalized pain management, and modernization of traditional medicine practices. Despite these advances, significant limitations persist, including lack of prospective validation in diverse populations, challenges in model interpretability, heterogeneity in data quality, and ongoing concerns regarding algorithmic bias and ethical implications. AI technology is positioned to augment rather than replace clinical expertise, offering enhanced precision, efficiency, and personalized patient care. However, successful implementation requires addressing fundamental challenges in model validation, regulatory approval, and clinical integration. Future progress depends critically on the development of explainable AI models, robust external validation, establishment of comprehensive regulatory frameworks, and thoughtful integration strategies that preserve essential human judgment, empathy, and the therapeutic relationship.

Keywords

Artificial intelligence; Machine learning; Hybrid AI; Monte Carlo simulation; Neural networks; Anesthesia; Intensive care; Emergency medicine; Palliative care; Pain management; Traditional Chinese medicine; Clinical decision support; Predictive analytics; Large language models; Deep learning; Healthcare automation

Artificial intelligence articles; Machine learning articles; Hybrid AI articles; Monte Carlo simulation articles; Neural networks articles; Anesthesia articles; Intensive care articles; Emergency medicine articles; Palliative care articles; Pain management articles; Traditional Chinese medicine articles; Clinical decision support articles; Predictive analytics articles; Large language models articles; Deep learning articles; Healthcare automation articles.

Article Details

1. Introduction

1.1 Historical context and evolution of AI in medicine

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into healthcare represents one of the most transformative and rapidly evolving trends in modern medicine. The journey began in the 1970s with knowledge-driven systems such as MYCIN, an expert system developed at Stanford University that used rule-based reasoning to diagnose bacterial infections and recommend antibiotics. While MYCIN demonstrated expert-level performance, its reliance on manually encoded rules limited scalability and adaptability.

Contemporary medical AI has evolved into primarily data-driven approaches, characterized by exponential advances in computational capacity, unprecedented data availability, and sophisticated machine learning (ML) techniques that fundamentally reshape clinical practice across diverse medical disciplines. The convergence of several key factors has created an optimal environment for AI adoption: the widespread implementation of electronic health records (EHRs), the proliferation of continuous monitoring devices, advances in cloud computing infrastructure, and the development of increasingly sophisticated algorithms capable of processing complex, multimodal healthcare data.

1.2 Three paradigms of modern medical AI

Contemporary AI applications in healthcare can be categorized into three complementary paradigms, each addressing different aspects of clinical decision-making:

Knowledge-driven AI systems, exemplified by MYCIN and early expert systems, rely on explicit rule-based reasoning encoded by domain experts. While largely superseded by data-driven approaches, these systems established foundational principles for explainability and clinical integration that remain relevant today.

Data-driven AI encompasses machine learning, neural networks, deep learning, and large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT and Gemini. These systems learn patterns directly from data without explicit programming. Machine learning algorithms excel at risk stratification and outcome prediction using structured clinical data. Deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has revolutionized medical image interpretation, achieving expert-level performance in radiology, pathology, and ultrasound analysis. Large language models, the most recent advancement, demonstrate remarkable capabilities in natural language understanding, clinical documentation, and patient communication, though they require careful validation in medical contexts.

Probabilistic methods, including Monte Carlo simulations and Bayesian approaches, quantify uncertainty in predictions—a critical capability for clinical decision-making. These methods can model variability in vascular resistance, circulating blood volume, and intervention effects (e.g., vasopressor or fluid administration), enabling clinicians to understand prediction stability and risk distributions under different clinical scenarios.

Modern medical AI increasingly adopts a hybrid approach, integrating data-driven predictions with probabilistic uncertainty quantification and domain knowledge constraints. This synthesis addresses limitations of individual paradigms while preserving interpretability and clinical relevance.

1.3 Technical foundations: neural networks and activation functions

Understanding the technical foundations of deep learning is essential for clinical implementation. Neural networks consist of interconnected layers of artificial neurons, each performing weighted summation of inputs followed by nonlinear transformation through an activation function. The hierarchical structure of deep networks—comprising input layers, multiple hidden layers, and output layers—enables automatic feature extraction and representation learning from raw data.

Activation functions introduce essential nonlinearity that allows neural networks to model complex patterns. Historical approaches used sigmoid or hyperbolic tangent (tanh) functions, which map inputs to bounded ranges (0-1 for sigmoid, -1 to 1 for tanh). However, these functions suffer from vanishing gradient problems in deep networks. Contemporary architectures predominantly employ Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) functions and their variants (Leaky ReLU, Parametric ReLU), which output the input directly if positive and zero (or a small negative value) otherwise. ReLU functions facilitate deeper network training, accelerate convergence, and have become the de facto standard in medical image analysis and signal processing applications. Recent theoretical work has revealed universal scaling laws governing signal propagation in deep networks with ReLU activation, providing principled guidance for architecture design.

In this review, "artificial intelligence (AI)" is used as an umbrella term encompassing three methodological categories: knowledge-driven systems (e.g., the historical MYCIN system from the 1970s which utilized rule-based reasoning), data-driven approaches (e.g., machine learning [ML], deep learning [DL], and large language models [LLMs]), and probabilistic methods (e.g., Monte Carlo simulation). The hierarchical relationship is defined such that DL is a subset of neural networks (NN), which is a subset of ML, which in turn falls under AI (DL ⊂ NN ⊂ ML ⊂ AI). While contemporary medical AI predominantly relies on data-driven models, probabilistic methods serve a critical complementary role by quantifying uncertainty, facilitating the development of "Hybrid AI" frameworks essential for robust clinical decision-making.

Understanding the technical foundations of these systems is essential for clinicians. Neural networks, the backbone of modern DL, consist of input, hidden, and output layers where information processing mimics synaptic transmission. The activation functions within these nodes, such as the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) or Leaky ReLU, determine the output signal. Notably, the sigmoid activation function historically parallels the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve—a relationship fundamental to the pulse oximetry principle (PaO2 vs. SpO2)—illustrating the mathematical continuity between physiological modeling and modern AI architectures.

The application of AI is particularly pertinent and promising in clinical specialties that are inherently data-rich, time-critical, and decision-intensive. Anesthesiology, intensive care medicine, and emergency medicine exemplify these characteristics, making them natural pioneers in AI integration. These specialties routinely generate vast amounts of high-frequency physiological data, require rapid decision-making under conditions of uncertainty, and benefit significantly from predictive analytics and automated monitoring systems. The unique characteristics of these specialties—including continuous patient monitoring, complex pharmacological interventions, and the need for immediate response to physiological changes—create an ideal environment for AI-driven clinical decision support.

Historically, anesthesiology was among the first medical specialties to embrace technological innovation, from the introduction of pulse oximetry and capnography to the development of sophisticated monitoring systems and drug delivery devices. This tradition of technological adoption has naturally extended to AI applications, with early implementations focusing on anesthetic depth monitoring, automated drug delivery, and perioperative risk prediction. Similarly, intensive care medicine, with its reliance on continuous monitoring and data- driven decision-making, has emerged as a fertile ground for AI applications ranging from early warning systems to predictive models for clinical deterioration.

Over the past decade, AI applications have expanded beyond acute care specialties into areas traditionally considered less amenable to technological intervention. Palliative medicine, pain management, and even traditional East Asian medicine are increasingly incorporating AI-driven approaches to enhance clinical care, optimize treatment selection, and improve patient outcomes. This expansion reflects both the maturation of AI technology and growing recognition of its potential to address complex clinical challenges across the entire spectrum of healthcare delivery.

The COVID-19 pandemic has served as a significant catalyst for AI adoption in healthcare, highlighting the critical need for predictive analytics, resource optimization, remote monitoring capabilities, and automated decision support systems. The pandemic demonstrated both the potential of AI to address large-scale healthcare challenges and the importance of robust, validated systems that can perform reliably under extreme conditions. Lessons learned during this period have informed current approaches to AI development and implementation, emphasizing the need for rigorous validation, ethical considerations, and careful integration with existing clinical workflows.

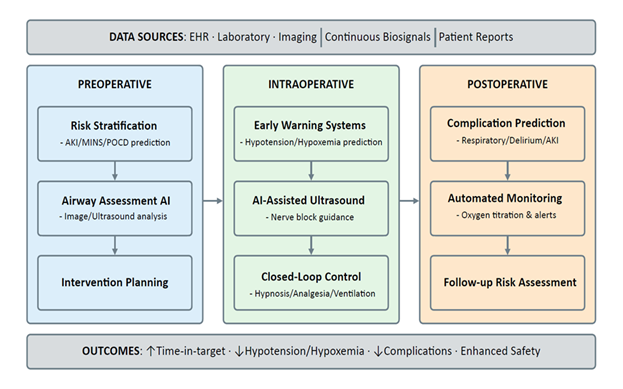

2. AI in Anesthesia and Perioperative Medicine

Anesthesiology is unusually well-suited to AI because it generates continuous, high-frequency physiologic waveforms, device parameters, imaging, and interventions recorded at exact times within a tightly controlled environment. These data streams enable three practical capabilities: bedside prediction and early warning, perioperative risk stratification that informs preparation and surveillance, and automation through closed-loop control of hypnosis, analgesia, and ventilation/oxygenation. In clinical use, the most effective systems pair predictions with clear action pathways or machine-executable targets, emphasize transparency and calibration, and ensure clinicians can take control instantly whenever needed. Evidence to date shows consistent improvements in process quality (e.g., time in target, fewer manual adjustments, better image acquisition) with mixed but growing signals for patient-centered outcomes (Figure 1).

2.1 Prediction and early warning at the bedside

Intraoperative hypotension (IOH) is common and consistently linked to postoperative organ injury. Large perioperative cohorts show graded risk with both severity and duration of low mean arterial pressure (MAP). Even brief exposures below approximately 55 mmHg are associated with myocardial injury and acute kidney injury (AKI), while time spent below 60-65 mmHg also correlates with harm, supporting proactive avoidance of these ranges [1,2]. These relationships persist after risk adjustment across surgical populations, motivating bedside systems that forecast imminent IOH events, typically defined as “MAP < 65 mmHg for > 1 min in the next 5-15 min”, to shift care from reactive rescue to anticipatory management. A prominent approach is the Hypotension Prediction Index (HPI), a machine-learning (ML) model trained on high-fidelity arterial waveforms that captures subtle beat-to-beat features reflecting emerging failure of preload, afterload, contractility compensation, and produces a 0-100 risk score [3]. Prospective evidence suggests that prediction must be coupled to action. In a randomized clinical trial, integrating an HPI-based early-warning workflow with a structured hemodynamic diagnostic/treatment algorithm significantly reduced intraoperative hypotension compared to standard care, demonstrating process improvement while underscoring the need for multicenter trials powered to evaluate patient-centered outcomes [4].

Prediction is no longer only about blood pressure. Real-time ML models trained on perioperative data can warn of intraoperative hypoxemia minutes before it happens. Some systems also provide brief, case-specific explanations, such as low tidal volume or rising oxygen needs, which help clinicians understand and respond to the alert. In testing, these explanations improved the anticipation and prevention of desaturation [5]. Beyond the OR, continuous oximetry and capnography in the PACU and on surgical wards provide early warning of opioid-related respiratory depression. The multicenter PRODIGY risk prediction model uses five simple bedside variables (age, sex, opioid-naïve status, sleep-disordered breathing, heart failure) to flag high-risk patients. It has been validated against clinical and resource outcomes [6].

Important limitations remain. Model performance can decline when models are transferred to new hospitals, devices, or patient groups; recent reviews recommend multicenter validation and ongoing monitoring after deployment [7]. The standard event definition, MAP < 65 mmHg for more than 1 minute, is convenient but imperfect. Relative drops or patient-specific targets may better reflect perfusion risk and should be studied [1,2]. Most trials improve process measures (e.g., time in hypotension) rather than hard outcomes such as AKI or myocardial injury, which need larger, carefully controlled studies [2,4,7]. Finally, many waveform-based tools require an arterial line, which limits use; broader impact will likely depend on noninvasive signals or hybrid approaches [7].

2.2 Machine learning in perioperative risk stratification

Machine learning models are increasingly used to convert preoperative demographics, comorbidity profiles, laboratory data, and intraoperative signals into individualized risk estimates for major postoperative complications. Recent systematic reviews in perioperative medicine conclude that discrimination is often promising. Still, external validation, calibration reporting, and impact evaluation remain inconsistent, underscoring the need for methodologically rigorous development and validation pipelines [8].

Acute kidney injury illustrates both potential and pitfalls. Large noncardiac surgical cohorts have yielded interpretable machine learning models that achieve AUCs around 0.83-0.85 using preoperative and intraoperative features, with only modest performance loss when restricted to preoperative variables. This pattern is helpful for early counseling and optimization [9]. Calibration curves and feature attribution (e.g., age, preoperative serum creatinine, surgical duration) facilitate clinical interpretability, but multicenter external validation and clinical utility testing are required before routine adoption.

For myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery, explainable multicenter models have outperformed traditional scores in development and internal validation; however, their performance typically drops on external datasets, highlighting the importance of transportability assessments and threshold selection tailored to local prevalence [10].

Neurocognitive outcomes are also an active area. Prospective and real-world evaluations of delirium risk models demonstrate acceptable discrimination and operational feasibility in surgical inpatients. Live clinical deployment has been associated with increased detection and changes in sedative/antipsychotic use; nevertheless, the benefits of these outcomes require further study [11].

Beyond model performance, implementation matters. A randomized clinical trial in anesthesiology investigated whether presenting clinicians with machine learning predictions improved their own risk estimates for 30-day mortality and acute kidney injury. Assistance did not significantly improve AUC for clinician predictions, emphasizing that risk models should be embedded within action pathways (e.g., prompts for troponin/creatinine surveillance, hemodynamic, or nephroprotective bundles) rather than presented in isolation [12].

2.3 Deep learning for difficult airway assessment

Deep learning (DL) systems for airway assessment aim to reduce unanticipated difficulty by converting routine preoperative data, facial photographs, ultrasound measurements, and imaging into quantitative risk estimates that complement bedside tests [13,14]. DL models trained on facial images can flag patients at risk for a poor laryngoscopic view or difficult intubation, in some cohorts, outperforming classic scores. A recent study shows these tools can run on smartphone photographs taken at the bedside, which lowers the barrier to use in the preoperative clinics [15]. Models that show which visual features drove the prediction (e.g., highlighting limited mouth opening, neck contour, or jawline cues) can help clinicians plan devices and backup strategies, rather than simply providing a “difficult/not difficult” label [16].

Beyond photographs, ultrasound adds soft-tissue information that simple inspection misses [17]. Prospective work shows that combining ultrasound measurements (e.g., skin-to-epiglottic distance, tongue thickness, thyromental metrics) with standard clinical tests improves discrimination for difficult laryngoscopy compared with either alone [18,19]. In small single-center studies, composite ultrasound-clinical models have reported AUCs around 0.75-0.85 with high negative predictive values (93-99%) [18,19]. Tongue thickness alone shows more variable performance (AUC 0.92 for predicting difficult laryngoscopy, 0.69 for difficult intubation; negative predictive values 76% for difficult intubation) [20].

Imaging-based approaches extend this idea. A large study trained a DL model on lateral cervical radiographs and predicted Cormack-Lehane grade 3 or 4 views with high internal performance [21]. Radiomics work has combined clinical measurements with 3D CT features to estimate the risk of difficult mask ventilation in oral and maxillofacial surgery populations [22]. Three-dimensional facial scans have also been used to model facial geometry associated with mask seal and ventilation difficulties in prospective cohorts [23].

2.4 CNN-based image segmentation for tracheal intubation

Recent advances in convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and image segmentation have enabled the development of AI-assisted systems for airway management. Tracheal intubation fundamentally relies on the rapid visual identification of laryngeal structures, including the epiglottis, vocal cords, arytenoids, and the glottic opening. From a computer vision perspective, this task can be formulated as a semantic or instance segmentation problem, in which anatomically relevant regions are identified at the pixel level.

Fully convolutional networks (FCNs) and their derivatives, such as U-Net [24] and SegNet architectures [25], have demonstrated strong performance in medical image segmentation tasks due to their ability to preserve spatial resolution while extracting hierarchical features. These architectures are particularly suitable for real-time analysis of laryngoscopic images and video streams, as they enable dense prediction without reliance on fully connected layers. In airway management, FCN-based models can be trained to segment the glottic opening and surrounding soft tissues, thereby providing objective, real-time visualization of airway anatomy during intubation attempts.

Instance segmentation techniques, such as Mask R-CNN [26], may offer additional advantages in difficult airway scenarios, where edema, tumors, secretions, or anatomical variants obscure the laryngeal view. By separating individual anatomical structures within the same class, instance-level models can support airway identification even under suboptimal visualization conditions. Such approaches align with the concept of human-in-the-loop AI, in which the system augments rather than replaces clinical judgment [27].

Important caveats remain. Most studies are single-center and use different reference standards for “difficulty,” predicting a difficult laryngoscopic view (e.g., Cormack-Lehane 3-4), a difficult intubation (defined as failed or requiring multiple attempts), or difficult mask ventilation. Therefore, performance may not be consistent across different populations, devices, or teams [13,14,21]. Recent reviews recommend larger, multicenter, prospective studies with external validation, reporting of calibration and fairness across subgroups, and trials that test whether model-guided preparation reduces hypoxemia, failed first attempts, or the need for escalation to a surgical airway [14]. Until such evidence accumulates, these tools are best used as decision aids that complement a thorough airway examination and plan [17].

2.5 Deep learning-assisted ultrasound for peripheral nerve blocks

Deep learning-assisted ultrasound systems for peripheral nerve blocks utilize computer vision to highlight nerves, vessels, and relevant fascial planes on live scans, aiming to simplify view acquisition and interpretation for clinicians. In an external validation across nine block regions, an assistive overlay correctly identified target structures in most cases and was judged likely to reduce the risk of adverse events or block failure [28]. In a randomized study involving non-expert anesthetists, assistance increased the rate of acquiring an acceptable block view. It improved the correct identification of sono-anatomy compared to standard scanning [29]. A subsequent randomized crossover study suggested these benefits were still present two months after training, indicating potential support for skill retention beyond the immediate teaching period [30]. Recent scoping reviews map a rapidly growing literature and conclude that computer vision assistance can standardize scanning and accelerate learning, while emphasizing the need for robust prospective trials that link assistance to patient-centered outcomes such as block success and complications [31-33].

On the algorithmic side, multiple groups report the use of deep-learning models for nerve detection and segmentation in common block regions. Studies have demonstrated automatic localization of the interscalene brachial plexus on ultrasound [34,35] and femoral nerve segmentation with good agreement to expert annotations [36]. An evaluation compared AI-based nerve segmentation across the brachial plexus, femoral, and sciatic regions, highlighting both the promise of these tools and the need for standardized benchmarks and clinical endpoints [37]. Limitations across the literature include single-center designs, heterogeneity in probes and machines, small datasets, and a focus on process measures (acceptable view, time to view, trainee confidence) rather than patient outcomes; generalizability and post-deployment monitoring remain priorities for future work [31-33,37].

2.6 Machine learning-assisted closed-loop control in anesthesia

Contemporary “autonomous” anesthesia is best understood as a form of supervised autonomy. Clinicians set goals and safety limits, and the software adjusts drug delivery to keep EEG-derived depth of anesthesia and nociception surrogates within target ranges [38]. Design principles emphasize robust feedback signals, conservative control rules, explicit limits and alarms, and the ability for the clinician to take over immediately [39]. Evidence syntheses of intravenous closed-loop systems suggest tighter time in target and small efficiency gains, while underlining variable bias, heterogeneity, and the need for outcome-powered trials [40].

Hypnosis–closed-loop TIVA: Randomized trials comparing BIS-guided closed-loop propofol with manual control show more time spent with BIS values of 40-60 and fewer overshoots during induction and maintenance [41]. A multicenter trial of a Bayesian controller similarly achieved better hypnosis control than manual titration [42]. Pediatric data indicate feasibility and smoother depth control in preschool children without added adverse events [43]. Early reports of dual-drug loops (propofol and remifentanil) demonstrate technical feasibility, but larger trials are needed to illustrate patient-centered benefits [44]. Overall, closed-loop TIVA improves process metrics and may reduce drug use or recovery times, yet generalizability across monitors/patient groups remains a key gap [40].

Analgesia–nociception-guided titration: ML-supported nociception monitors (e.g., Nociception Level: NOL, Analgesia Nociception Index: ANI) convert multi-signal physiology into a real-time pain surrogate, guiding intraoperative opioid dosing [45,46]. A pooled analysis of two RCTs found lower PACU pain and fewer cases of severe pain with NOL-guided fentanyl vs standard care [46]. A meta-analysis reported reduced postoperative pain and opioid consumption with NOL guidance. However, effects on postoperative nausea and vomiting and length of stay were not significant, and study results varied widely [45]. A network meta-analysis across five nociception monitors suggested monitor-guided strategies can improve perioperative analgesic use and early pain endpoints, while stressing the need for standardized protocols and outcome trials [47]. For ANI, a systematic review and meta-analysis in patients under sedation or general anesthesia reported moderate diagnostic accuracy and lower opioid use with ANI-guided care, again with considerable variation between studies [48].

Ventilation and oxygenation automation: Closed-loop ventilatory controllers adjust respiratory rate, tidal volume/pressure support, FIO2, and sometimes PEEP to keep end-tidal CO2 and SpO2 within targets while limiting undue pressures/volumes. In perioperative and immediate postoperative settings, these systems have reduced the need for manual adjustments and kept patients closer to the intended gas-exchange and “lung-protective” ranges compared with clinician-set modes, without generating new safety signals [49,50]. In a randomized trial following cardiac surgery, fully automated ventilation increased the time spent in lung-protective settings, reduced severe hypoxemia, and accelerated the return to spontaneous breathing compared to conventional ventilation [51]. In an ICU randomized trial, closed-loop ventilation required fewer manual interventions and achieved more time with optimal SpO2 and tidal volume than conventional modes over 48 hours [50]. Automated oxygen titration is maturing in parallel. In patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure receiving high-flow nasal oxygen, a randomized crossover trial demonstrated that closed-loop FIO2 control increased time spent within the individualized SpO2 range and reduced bedside workload compared to manual titration [52]. A meta-analysis reported substantially more time within prescribed SpO2 targets and signals for less hypoxemia and lower workload with closed-loop oxygen control [53].

3. AI in Critical and Intensive Care Medicine

The intensive care unit (ICU) represents an optimal environment for AI applications, characterized by continuous collection of high-dimensional physiological, laboratory, and imaging data from critically ill patients who require immediate intervention for life-threatening conditions. The complexity of critical care decision-making, combined with the volume and velocity of data generation, creates unique opportunities for AI-driven clinical support systems to enhance patient care and outcomes.

3.1 Early warning systems and sepsis prediction

Biesheuvel et al. [7] outlined a comprehensive framework for AI integration in acute and intensive care, highlighting three primary domains of application: forecasting clinical deterioration, predicting sepsis onset, and optimizing resource allocation [7]. Their analysis emphasized the potential for ML systems to process vast amounts of continuously generated data to identify subtle patterns indicative of impending clinical deterioration, often hours before traditional monitoring approaches would detect changes. These early warning systems represent a paradigm shift from reactive to proactive critical care management.

Muşat et al. [54] conducted systematic reviews of machine learning (ML) in sepsis, covering both deterioration and outcome predictions [54]. They consistently reported encouraging discrimination but emphasized the heterogeneity of sepsis definitions, time windows, predictors, and validation strategies. Recent years have seen a shift from retrospective model development to implementation research. Adams et al. [55] reported a multisite prospective study examining associations between the deployment of an ML-based sepsis early warning system (TREWS) and improved process/outcome measures [55]. While demonstrating feasibility and some positive signals, the study also highlighted open questions about generalizability, alert fatigue, and causal attribution in real-world deployments. These findings underscore the critical importance of careful implementation strategies and ongoing monitoring when transitioning AI tools from development to clinical practice.

3.2 Diagnostic applications and risk stratification

The work by Yoon et al. [56] provided an extensive review of AI applications in critical care diagnostics, with particular emphasis on neuroimaging for traumatic brain injury and risk stratification for multi-organ failure [56]. Their analysis highlighted the superior performance of deep learning models in interpreting complex imaging studies, including computed tomography scans for intracranial hemorrhage detection and chest radiographs for pneumonia identification. These DL-driven diagnostic tools can provide rapid, accurate interpretations that support clinical decision-making, particularly in settings where immediate specialist consultation may not be available.

ARDS-focused systematic reviews by Tran et al. [57] and Yang et al. [58] have reported that ML supports diagnosis, risk stratification, and mortality prediction [57,58]. Performance depends strongly on dataset scale, feature availability, and external validation. These studies demonstrate AI's potential to identify patients at risk for developing ARDS before clinical criteria are fully met, enabling earlier intervention and potentially improved outcomes. However, the heterogeneity of ARDS definitions, variable timing of predictions, and differences in patient populations across studies limit generalizability and highlight the need for standardized approaches.

3.3 Mechanical ventilation and respiratory support

Regarding mechanical ventilation, comprehensive reviews by Ahmed et al. [59] and Jiang et al. [60] have described ML applications in ventilator management, weaning prediction, and detection of patient–ventilator asynchrony [59,60]. These efforts are clinically aligned with reducing the duration of ventilation and associated complications. ML-driven weaning prediction models analyze multiple physiological parameters, ventilator settings, and patient characteristics to identify optimal timing for extubation attempts, potentially reducing the risks of both premature and delayed extubation. Patient-ventilator asynchrony detection algorithms can identify subtle mismatches between patient effort and ventilator delivery that may escape clinical observation, enabling timely adjustments that improve comfort and potentially reduce ventilator-induced lung injury. However, these applications remain limited by heterogeneous labels, varying definitions of successful weaning, and bedside integration barriers.

3.4 Workflow optimization and clinical decision support

Saqib et al. [61] expanded the scope of AI applications in critical illness, providing a comprehensive assessment of impacts on workflow efficiency, patient monitoring, and safety outcomes [61]. Their review demonstrated that AI implementation in critical care settings can significantly reduce alarm fatigue through intelligent filtering of physiological alerts, improve medication dosing accuracy through predictive pharmacokinetic models, and enhance communication between healthcare team members through automated documentation and clinical summaries. These workflow enhancements have the potential to reduce cognitive burden on clinicians, allowing more time for direct patient care and complex decision-making.

The nursing perspective on AI in critical care, as examined by Porcellato et al. [62], revealed important insights into the practical implementation challenges and opportunities [62]. Their systematic review emphasized AI's potential to optimize nursing workload distribution, enhance patient risk monitoring, and support clinical decision-making at the bedside. The integration of AI tools into nursing workflows requires careful consideration of user interface design, alert management, and the preservation of critical thinking skills among healthcare providers. Successful implementation depends on engaging nurses early in the design process and ensuring that AI systems complement rather than complicate existing workflows.

3.5 Large language models in critical care

The emergence of large language models (LLMs), a class of deep learning-based generative AI, introduces entirely new possibilities for AI application in intensive care settings [63]. These sophisticated natural language processing systems can automate clinical documentation, provide decision support through analysis of medical literature, facilitate patient and family communication, and support medical education through interactive learning platforms. However, the implementation of LLMs in critical care requires careful validation to ensure accuracy, reliability, and appropriate integration with existing workflows. Concerns about hallucinations, outdated information, and liability must be addressed before widespread clinical adoption.

3.6 Current barriers and future directions

Despite these promising applications, substantial barriers to routine ICU-scale deployment persist. Prospective validation in diverse patient populations remains limited, with most studies conducted in single centers or specific patient subgroups. Transportability across different ICU environments, with varying patient populations, staffing models, and technical infrastructure, represents a significant challenge. Model interpretability remains critical for clinical acceptance, as intensivists require understanding of why a particular prediction or recommendation was generated. Governance frameworks that define roles, responsibilities, and liability for AI-assisted decisions are still evolving. Moving forward, AI should be deployed as a supervised clinical tool that augments expertise within regulatory and ethical frameworks that preserve human judgment, clinical autonomy, and the irreplaceable value of experienced intensivists in managing complex, critically ill patients.

4. AI in Emergency Medicine

Emergency departments (EDs) generate large volumes of clinical data, yet many high-stakes decisions must be made within minutes. In major trauma, acute coronary syndromes, and acute ischemic stroke, small delays can translate into irreversible organ injury and worse long-term function. The field’s familiar shorthand—“golden hour,” “time is brain,” “time is myocardium”—reflects a system that is highly sensitive to technologies capable of removing avoidable latency between arrival, diagnostic clarification, and definitive treatment.

However, ED presentations are frequently undifferentiated, and diagnostic uncertainty is often greatest at the point where time pressure is most intense. In this setting, false-positive outputs risk increasing cognitive load, contributing to alert fatigue, and prompting unnecessary escalation or intervention. False-negative outputs can be more consequential still, because they may suppress urgency when it is most needed and delay time-critical care. ED-facing AI therefore needs to be assessed as a clinical intervention embedded in work: who receives the output, what thresholds trigger action, what safeguards exist, and how responsibility is assigned when recommendations are followed—or ignored.

Recent reviews have underscored both the breadth of development and the fragility of real-world translation. Farrokhi et al. [64] catalogued AI applications spanning prehospital care, emergency radiology, triage and patient classification, diagnostic and interventional support, trauma and pediatric emergency care, and outcome prediction, while emphasizing that most published work remains retrospective and that prospective trials are required to establish true clinical value [64]. Amiot et al. [65] similarly reviewed recent advances in AI and emergency medicine, balancing opportunities and challenges—illustrating how AI holds promise for improving emergency care while emphasizing the need for careful attention to explainability, bias, privacy, and validation across diverse settings [65]. Taken together, these syntheses point to a practical lesson for emergency care: workflow design often determines whether an algorithm improves timeliness without compromising safety.

A useful way to keep this problem clinically grounded is to organize ED AI by system function—that is, where in the acute pathway a tool intervenes and which delays it is meant to remove. Here, ED AI can be framed as three complementary functions: (1) front-end prioritization, (2) diagnostic acceleration, and (3) operational optimization. This structure aligns with how emergency care fails under strain: mis-prioritization at the front door, bottlenecks in high-throughput diagnostics, and throughput collapse during crowding. It also keeps attention on actionable effects—earlier recognition, earlier escalation, earlier definitive care—rather than prediction as an end in itself.

4.1 Front-end prioritization

Front-end prioritization concerns decisions closest to entry into emergency care: triage, initial clinician assessment, and (in some systems) prehospital screening. The unit of action is the individual patient. The clinical aim is to support consistent choices about who must be seen first, who can safely wait, and which time-sensitive pathways should begin before diagnostic certainty is established. Inputs are typically limited to data available at triage— vital signs, age, chief complaint, brief text, and proxies for comorbidity—because any requirement for delayed testing defeats the purpose.

Two influential studies illustrate how routinely collected triage data can support meaningful early risk stratification. Raita et al. [66], using adult ED data from the National Hospital and Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS, 2007–2015), trained several machine-learning models using triage-available predictors (demographics, vital signs, chief complaints, comorbidities) and compared them with a conventional approach based on Emergency Severity Index (ESI) level [66]. They evaluated outcomes that map directly to early prioritization—critical care (ICU admission or in-hospital death) and hospitalization (admission or transfer)—and reported better discrimination with machine learning than the ESI-based reference model (e.g., AUC 0.86 vs 0.74 for critical care in the deep neural network model). The implication is not that triage should be automated, but that clinically useful signals exist in early data and can help identify high-risk patients who may be embedded within apparently lower-acuity strata.

Levin et al. [67] developed an electronic triage tool (“e-triage”) based on a random forest model that predicts the need for critical care, an emergency procedure, and inpatient hospitalization in parallel, then translates predicted risk into triage-level designations [67]. In a multisite retrospective study of 172,726 ED visits, e-triage showed AUC values ranging from 0.73 to 0.92 and was reported to improve identification of acute outcomes relative to ESI, particularly within ESI level 3—a large, heterogeneous group in many ED. When matched to the ESI distribution, e-triage identified more than 10% of ESI level 3 patients as needing up-triage; those up-triaged patients had higher rates of critical care or emergency procedure (6.2% vs 1.7%) and hospitalization (45.4% vs 18.9%). This addresses a common operational failure mode: when workload rises, heterogeneity within “middle acuity” categories can obscure time-critical illness unless reassessment is frequent and systematic.

A central question, however, is whether front-end tools change timelines and outcomes rather than only improving retrospective discrimination. A concrete example comes from a multisite quality improvement study by Hinson et al. [68] evaluating an AI-informed, outcomes-driven triage decision support system for adults presenting with chest pain [68]. At arrival, TriageGO estimates probabilities for critical care, emergency procedures, and hospital admission from variables including demographics, arrival mode, vital signs, chief complaints, and active medical problems, then recommends an acuity level. Implementation across three EDs was staggered between 2021 and 2023, and the tool replaced ESI at those sites. After adjustment, length of stay for hospitalized patients decreased (by 76.4 minutes), and time to emergency cardiovascular procedures decreased (by 205.4 minutes; cardiac catheterization by 243.2 minutes), without observed changes in 30-day mortality or 72-hour ED returns requiring hospitalization or emergency procedures. Even allowing for the limitations inherent to quality improvement designs, this study is valuable because it evaluates a triage algorithm using endpoints that matter to ED systems: time-to-procedure, throughput, and proximate safety signals.

Across these examples, the operational lesson is consistent. Front-end prioritization tools are most defensible when they do not simply add alerts, but instead tighten the mapping between early data and predetermined actions (earlier reassessment, earlier senior review, earlier pathway activation) while monitoring both over-intervention and missed deterioration.

4.2 Diagnostic acceleration

Diagnostic acceleration targets time loss in high-throughput diagnostic steps where queues, interpretation delays, and communication friction become rate-limiting. In many ED pathways, the bottleneck is not ordering or acquiring a test, but the interval from data availability to interpretation, notification, and mobilization of the team capable of definitive treatment. Imaging-driven workflows are a natural focus because time-critical conditions often require CT or CT angiography, and because rapid benefit depends on converting findings into coordinated action.

Acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion (LVO) has become a leading implementation target because the workflow has discrete, measurable milestones and clear time dependence. Martinez-Gutierrez et al. [69] conducted a cluster randomised stepped-wedge clinical trial across four comprehensive stroke centers (January 2021 to February 2022) assessing automated CT angiogram interpretation coupled with secure group messaging [69]. The intervention produced real-time alerts to clinicians and radiologists within minutes of CT completion. Among included patients treated with thrombectomy, implementation was associated with a reduction in door-to-groin time by 11.2 minutes (95% CI −18.22 to −4.2) and a reduction in time from CT initiation to endovascular therapy start by 9.8 minutes (95% CI −16.9 to −2.6), with no differences in IV thrombolysis times or hospital length of stay. The mechanism is clinically intelligible: earlier notification advances team mobilization and compresses communication delays that often sit between imaging and procedure.

This example also clarifies what “diagnostic AI” must include to matter in emergency care. Detection alone is insufficient if outputs are not routed to the responsible team, if thresholds are poorly calibrated to local prevalence, or if the tool disrupts the radiology–ED interface. Reviews focused on emergency imaging highlight both the promise of rapid interpretation support and the persistent implementation challenges—bias, privacy, and the need for extensive validation across institutions and patient groups. For diagnostic acceleration, therefore, the key evaluation endpoints are not limited to sensitivity or AUC, but include time-to-notification, time-to-team activation, time-to-definitive intervention, and the downstream consequences of false alarms (avoidable mobilization) and misses (avoidable delay).

4.3 Operational optimization

Operational optimization addresses system-level delays driven by congestion, crowding, and downstream capacity constraints. Even when diagnoses are recognized promptly and pathways are activated appropriately, definitive care can be delayed by boarding, bed shortages, imaging queues, and staffing mismatches. Operational AI tools therefore focus on forecasting and resource allocation: predicting near-term arrivals and acuity mix, anticipating bottlenecks, estimating admission likelihood early enough to trigger bed management, and supporting staffing or space adjustments intended to stabilize flow.

Here, the evidence base is expanding, but also uneven. Farimani et al. [70] systematically reviewed models predicting ED length of stay and identified substantial heterogeneity, with common shortcomings in reporting and methodological quality [70]. Among included studies, only a minority externally validated models, and several recurrent issues were noted—predictor selection practices, sample size considerations, reproducibility, handling of missing data, and problematic dichotomization of continuous variables. These limitations matter because operational predictions are highly sensitive to local practice patterns (testing thresholds, admission policies, staffing), and transport poorly across institutions without careful recalibration and monitoring.

Demand forecasting faces similar challenges. Blanco et al. [71] reviewed AI-based models for hospital ED demand forecasting (2019–2025) and found that machine learning and deep learning methods often outperform classical time series approaches, particularly when external variables—weather, air quality, and calendar effects—are incorporated [71]. Yet the same review noted limited external validation and relatively infrequent use of interpretability methods, both of which constrain confident deployment. The consequence is that operational tools must be treated as part of governance and planning, not simply as technical add-ons: forecasts need explicit decision hooks (e.g., staffing triggers, surge bed activation thresholds) and a process for auditing whether actions actually reduce waiting, boarding, or time-to-critical intervention.

Across all three functions, one requirement is constant: ED AI must be integrated into real work with clear accountability. Farrokhi et al. [65] emphasized that much of the field remains retrospective and that prospective trials are essential to establish value in emergency settings [65]. Function-based framing can help design those evaluations. Front-end prioritization should be studied using under-triage, time-to-senior review, time-to-pathway activation, and safety outcomes that capture over-intervention as well as missed deterioration. Diagnostic acceleration should be evaluated with pathway-relevant time endpoints (scan-to-notification, door-to-procedure) and measures of workflow burden (false alerts, unnecessary mobilization). Operational optimization should be judged on avoidable waiting and maintenance of access for time-critical patients under strain, rather than on predictive accuracy alone.

Finally, implementation requires continuous surveillance: performance drift monitoring, auditing of alerts and actions, and periodic recalibration as case mix, staffing, and processes change. Without these controls, ED AI is vulnerable to distribution shift and to subtle harm through misplaced confidence. Under appropriate governance, however, AI can contribute to the ED’s core objective: timely definitive care delivered safely in an environment defined by uncertainty and constraint.

5. AI in Palliative Care

Palliative care, traditionally characterized by nuanced clinical judgment, empathetic communication, and individualized approaches to complex psychosocial needs, represents an emerging frontier for machine learning application. While the integration of technology in this humanistic specialty requires careful consideration of ethical implications and preservation of the therapeutic relationship, machine learning tools are beginning to demonstrate significant potential in supporting clinicians and improving patient outcomes.

5.1 Prognostic modeling and identification of needs

Wilson et al. [72] conducted a landmark randomized clinical trial examining the effect of a machine learning-based decision support tool on palliative care referral patterns in hospitalized patients [72]. Their study demonstrated that the ML-driven system, which analyzed multiple data points including diagnosis, prognosis, functional status, symptoms, and healthcare utilization patterns, resulted in a statistically significant increase in appropriate referrals, earlier intervention, and improved patient and family satisfaction. This proactive approach addresses the longstanding challenge of delayed palliative care referrals, ensuring that patients receive symptom management and goal-concordant care earlier in their disease trajectory.

5.2 Quantitative comparison of machine learning models with traditional prognostic indices

Traditional prognostic tools in palliative care, such as the Palliative Prognostic Index (PPI) and Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), have demonstrated moderate discriminative ability for survival prediction. Stone et al. [73] reported that for 3-week survival prediction, PPS alone achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of approximately 0.71, while a simplified PPI incorporating PPS components achieved an AUROC of 0.87 [73]. For 6-week survival prediction, PPS demonstrated an AUROC of approximately 0.69, compared to 0.73 for simplified PPI. While these tools provide valuable clinical guidance, their reliance on single-time-point assessments limits their ability to capture disease trajectory dynamics.

Machine learning approaches that integrate longitudinal data demonstrate superior prognostic accuracy. Huang et al. [74] developed models incorporating actigraphy data (objective physical activity monitoring) alongside traditional clinical variables [74]. In their prospective validation, baseline Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) achieved an AUROC of 0.833, while PPI demonstrated an AUROC of 0.615. Actigraphy data alone substantially improved discrimination to 0.893, and the combination of actigraphy with clinical variables achieved an AUROC of 0.924. This substantial improvement reflects machine learning's capacity to model temporal dynamics and complex nonlinear interactions that static indices cannot capture. Such enhanced accuracy enables earlier and more confident advance care planning discussions, ensuring that interventions align with patients' values and goals. However, the communication of ML-generated prognostic information requires sensitivity and skill, ensuring that predictions are presented as ranges with appropriate uncertainty quantification and used to empower rather than distress patients.

5.3 Symptom management and communication support

The bibliometric analysis conducted by Pan et al. [75] revealed emerging research hotspots and trends in machine learning applications for palliative care [75]. Key areas of development include symptom assessment and management systems that continuously monitor patient-reported symptoms and recommend personalized interventions. Deep learning algorithms analyzing voice biomarkers or facial expressions can detect pain or distress in patients unable to communicate verbally, enabling more effective symptom control.

5.4 Depression and psychological distress detection

Depression represents one of the most prevalent and undertreated symptoms in palliative care populations, yet physical frailty, fatigue, and disease burden may limit patients' ability to articulate emotional suffering. Deep learning-based analysis of facial expressions, gaze behavior, head movements, and Facial Action Coding System (FACS) features has emerged as a promising approach for detecting and monitoring depressive states.

Studies using video-recorded clinical interviews have demonstrated that deep learning models trained on facial and behavioral features can discriminate between depressed and non-depressed individuals with high accuracy. Facial expression analysis using long short-term memory (LSTM) neural networks has achieved classification accuracy of approximately 91.7% and F1-scores of 88.9% in detecting depressive states [76]. Multimodal approaches integrating facial analysis with voice biomarkers and linguistic patterns show even greater potential, with some systems demonstrating sensitivity and specificity exceeding 80% for major depressive disorder detection [77]. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) score prediction using machine learning has achieved mean absolute errors of approximately 3.7 points, enabling continuous monitoring without repeated questionnaire administration [78].

Clinical implementation of these technologies requires careful consideration of contextual factors that may affect model performance, including cultural differences in emotional expression, effects of sedation or delirium, and fatigue-related changes in facial appearance. These systems should complement rather than replace clinical assessment, serving as screening tools that prompt comprehensive evaluation when concerning patterns are detected.

5.5 Large language models in palliative care communication

Large language models represent a distinct application domain, offering support for clinical communication and patient education. These systems can help clinicians prepare for difficult conversations by generating empathetic language frameworks for breaking bad news, simulating patient interactions for communication skills training, and creating personalized educational materials that explain complex medical concepts in accessible language tailored to individual health literacy levels. Furthermore, AI-driven bereavement support platforms can provide personalized resources and follow-up for grieving families, extending the continuum of care beyond the patient's death.

5.6 Ethical considerations and future outlook

The implementation of machine learning and AI technologies in palliative care requires rigorous attention to ethical considerations, including patient autonomy, data privacy protection, algorithmic transparency, cultural sensitivity in emotional expression interpretation, and the preservation of human connection in end-of-life care. There is a risk that reliance on algorithmic predictions could inadvertently lead to the "medicalization" of dying, introduce bias in resource allocation decisions, or create pressure for prognostic certainty that is incompatible with the inherent uncertainty of end-of-life trajectories.

Success depends on designing systems that augment rather than replace human judgment and empathy, ensuring that technology enhances rather than diminishes the therapeutic relationship between patients, families, and healthcare providers. Machine learning models should be presented as decision support tools that provide additional information to inform clinical judgment, not as definitive answers that dictate care decisions. Future research must focus on prospective validation in diverse cultural contexts, assessment of impact on patient-reported outcomes and quality of life, and ensuring alignment with the core values of palliative medicine: relieving suffering, honoring patient autonomy, and supporting dignity throughout the dying process.

6. AI in Pain Management

The management of chronic pain remains one of the most complex challenges in contemporary medicine, requiring integration of biological, psychological, and social dimensions. AI offers an increasingly powerful means of addressing this complexity by analyzing multimodal data, revealing hidden patterns, and generating individualized predictions that extend beyond the scope of conventional clinical reasoning. Recent advances in machine learning, deep learning, and natural language processing have positioned AI as a transformative tool in pain medicine, capable of enhancing assessment accuracy, guiding treatment decisions, and improving long-term outcomes.

Zhang et al. [79] conducted a comprehensive scoping review encompassing thirty studies that explored AI-based interventions for pain assessment and management [79]. Their analysis demonstrated that algorithms using facial recognition, thermography, data mining, and natural language processing could identify pain with remarkable precision, even in non-verbal or cognitively impaired patients. Deep learning approaches analyzing facial expressions achieved diagnostic accuracies exceeding 90%, while text-based classifiers reliably detected pain documentation within electronic health records. Other models integrated imaging and clinical data to predict postoperative or chronic pain trajectories, such as the development of persistent pain following breast surgery or microvascular decompression. Mobile-health applications that applied adaptive algorithms to deliver behavioral feedback improved self-management and functional outcomes among individuals with chronic back pain.

Complementary evidence is provided by Lo Bianco et al. [80], who examined the educational and communicative potential of generative AI in chronic opioid therapy [80]. In their cross-model assessment, large language models such as GPT-4 produced highly reliable and comprehensible responses to common patient inquiries about long-term opioid use, including addiction risk, tapering, and management of adverse effects. The study underscored that AI can serve as a valuable adjunct to patient education by offering accessible, empathetic, and evidence-based explanations. However, it also cautioned that technical accuracy and contextual nuance diminish when AI systems address complex pharmacological or individualized topics, reinforcing the necessity of clinical oversight and ongoing model refinement.

Synthesizing evidence from both studies, AI currently contributes to six interrelated domains of pain management: chronic pain phenotyping; personalized treatment recommendation; opioid risk assessment; real-time pain monitoring; predictive modeling of treatment response; and integrated care coordination. Despite encouraging results, implementation remains limited by the subjective nature of pain reporting, heterogeneity of datasets, and ethical concerns about privacy, transparency, and algorithmic bias. Most current models are trained on small, homogeneous samples, restricting generalizability.

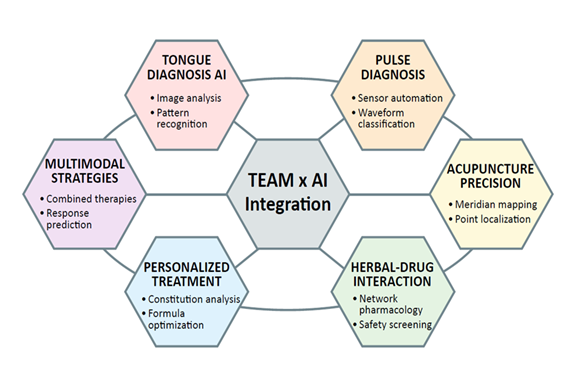

7. AI in Traditional and East Asian Medicine

The convergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and traditional East Asian medicine (TEAM) represents a remarkable synthesis of empirical wisdom and computational innovation. By translating the qualitative insights of traditional practices into quantifiable, data-driven frameworks, AI provides new means to modernize diagnostic systems, validate pharmacological mechanisms, and design personalized interventions that bridge ancient and modern paradigms (Figure 2).

Li et al. [81] demonstrated how AI has transformed multi-metabolite–multi-target modeling in herbal pharmacology [81]. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) relies on the synergistic interaction of multiple active compounds, yet such complexity historically limited mechanistic elucidation. Through multi-omics integration, deep learning, and cross-modal data fusion, AI now enables predictive modeling of compound–target networks, identification of synergistic bioactive components, and simulation of pharmacokinetic trajectories. These approaches surpass traditional reductionist methods, offering a systems-level understanding of polypharmacology while preserving TCM’s holistic framework.

Zhou et al. [82] expanded this technological foundation to industrial modernization of the TCM sector [82]. They emphasized AI’s role in standardization, quality assurance, and manufacturing optimization, addressing long-standing issues such as variability in raw materials and lack of reproducible extraction standards. Machine learning and computer vision tools enable automated quality grading, adulterant detection, and real-time process control, thereby aligning TCM production with international pharmaceutical norms.

The application of AI to acupuncture represents another frontier where computational precision meets clinical heritage. Wang et al. [83] described AI-directed acupuncture, in which data-mining algorithms such as the Apriori association rule reveal effective acupoint combinations for complex diseases, transforming empirical prescriptions into statistically validated treatment patterns [83]. Computer-vision systems record and analyze needle manipulation techniques, preserving expert craftsmanship and enhancing reproducibility in education. Furthermore, machine-learning models predicting treatment response can guide patient selection and optimize therapy parameters. Complementing these mechanistic and clinical perspectives, Zhou et al. [82] conducted a bibliometric analysis quantifying the global evolution of AI-acupuncture research, identifying exponential growth and dominant methodologies like deep learning [82].

Song et al. [84] assessed AI empowering TCM through extensive bibliometric analysis spanning 2004-2023, revealing exponential research growth particularly after 2019, with the United States and China as leading contributors and Harvard University as the most prolific institution [84]. Machine learning and deep learning emerged as dominant methodologies, reflecting the field's transition from traditional knowledge-driven to data-intensive computational approaches. Key application domains include AI-integrated TCM databases (TCMBank, ETCM v2.0, BATMAN-TCM 2.0) enabling target discovery and herb-drug interaction screening; ensemble learning and AlphaFold-based structure prediction for TCM compound activity; constitutional analysis and personalized diagnosis; pulse diagnosis automation; tongue diagnosis using computer vision; and meridian mapping with acupoint localization. Challenges include data heterogeneity, inconsistent curation standards, limited model interpretability, and the need for cross-disciplinary collaboration to align computational outputs with TEAM principles.

The integration of AI into TEAM holds particular relevance for anesthesiology and perioperative care. Traditional herbal formulations used in East Asian populations may interact with anesthetic agents, influence coagulation status, or affect perioperative hemodynamics. AI-driven herb-drug interaction databases can alert clinicians to potential risks during preoperative assessment. Additionally, AI-enhanced constitutional analysis and pulse diagnosis may complement Western risk stratification by capturing patient-specific vulnerabilities not readily apparent through conventional assessment. Pain management represents another intersection, where acupuncture guided by AI-derived acupoint selection algorithms could offer adjunctive analgesia in the perioperative period, potentially reducing opioid requirements. However, clinical integration requires rigorous validation of these tools in diverse populations and healthcare settings, ensuring that they augment rather than complicate existing perioperative care pathways.

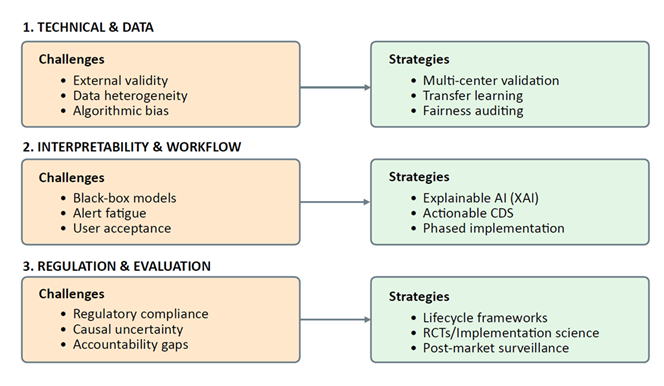

8. Current Limitations and Challenges

Despite the promising applications of AI across anesthesia, critical care, emergency medicine, palliative care, pain management, and traditional medicine, significant limitations constrain widespread clinical implementation. These challenges span technical, methodological, regulatory, and ethical domains, requiring coordinated efforts across multiple stakeholders to address (Figure 3).

8.1 Lack of prospective validation and external validation

The majority of AI models in medical literature are developed and validated using retrospective data from single institutions. While retrospective studies can demonstrate proof-of-concept and identify promising approaches, they are inherently limited by selection bias, missing data, and the inability to assess real-world clinical impact. External validation—testing models on data from different hospitals, patient populations, and healthcare systems—remains uncommon, yet it is essential for demonstrating generalizability. Models that perform excellently in development cohorts often show significant performance degradation when applied to external datasets due to differences in patient demographics, disease severity, clinical workflows, and data collection practices. Prospective validation studies, particularly randomized controlled trials that compare AI-assisted care with standard practice, are necessary to establish clinical utility and cost-effectiveness before widespread adoption.

8.2 Model interpretability and explainability

Many high-performing AI models, particularly deep neural networks, function as "black boxes" that provide predictions without transparent explanations of their reasoning. While techniques such as attention mechanisms, saliency maps, and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values offer some insight into model decision-making, they often fall short of the level of explanation required for clinical acceptance and regulatory approval. Clinicians need to understand not only what a model predicts but why it made that prediction, particularly when recommendations diverge from clinical judgment or when outcomes are adverse. Explainable AI (XAI) remains an active research area, with ongoing efforts to develop models that balance predictive performance with interpretability.

8.3 Data quality and availability

AI model performance is fundamentally dependent on the quality, completeness, and representativeness of training data. Electronic health records, the primary data source for many medical AI applications, contain numerous quality issues including missing values, inconsistent coding practices, temporal misalignment, and documentation variability across providers. Laboratory values may be missing-not-at-random, introducing bias when models impute or exclude these cases. Physiological waveforms from monitoring devices are susceptible to artifact, sensor malfunction, and calibration drift. Furthermore, available datasets often underrepresent certain demographic groups, socioeconomic strata, and geographic regions, raising concerns about algorithmic bias and health equity. The development of large, diverse, high-quality datasets with standardized formats and annotation remains a critical priority.

8.4 Algorithmic bias and health equity

AI models can perpetuate and amplify existing healthcare disparities if training data reflect historical biases in access to care, diagnostic practices, or treatment decisions. For example, models trained predominantly on data from academic medical centers may perform poorly in community hospitals or resource-limited settings. Race-based corrections in clinical algorithms have been criticized for reinforcing inequities; AI models that learn from such data may inadvertently incorporate these biases. Ensuring fairness requires deliberate attention to dataset composition, evaluation of model performance across demographic subgroups, and ongoing monitoring after deployment to detect and mitigate disparate impacts. The development of fairness-aware ML algorithms that explicitly optimize for equitable performance across protected groups represents an important research direction.

8.5 Regulatory and approval pathways

AI-based medical devices are regulated as Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) by agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). However, regulatory frameworks designed for traditional medical devices may not adequately address the unique characteristics of AI systems, including their ability to learn and evolve over time, their dependence on data infrastructure, and their potential for performance drift. The FDA has proposed a framework for regulating adaptive AI, but implementation details remain under development. Clear regulatory pathways that balance innovation with patient safety, define requirements for validation and post-market surveillance, and establish standards for algorithm transparency are essential for responsible AI deployment.

8.6 Clinical integration and workflow challenges

Successful AI implementation requires more than technical performance; it demands thoughtful integration into clinical workflows that enhances rather than disrupts care delivery. Poorly designed interfaces, excessive alerts, and lack of integration with electronic health record systems can lead to alert fatigue and user frustration, ultimately causing clinicians to ignore or override AI recommendations. The "human-in-the-loop" principle, ensuring that AI serves as a decision support tool rather than an autonomous agent, is critical for maintaining clinical judgment and accountability. Implementation science research examining barriers and facilitators of AI adoption, user experience design, and change management strategies will be essential for translating promising technologies into routine clinical practice.

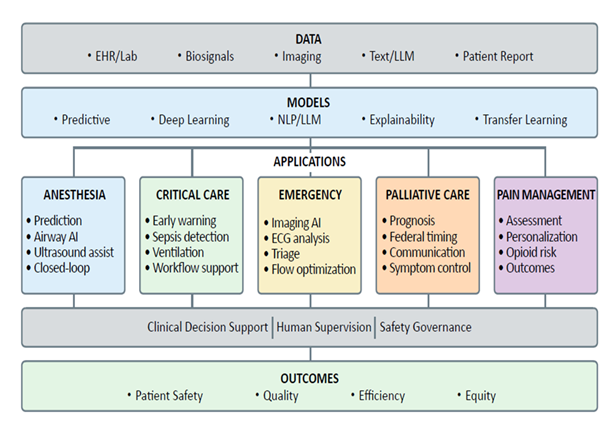

9. Future Directions and Research Priorities (Figure 4)

Advancing AI applications in healthcare requires coordinated efforts across multiple domains. Key research priorities include:

9.1 Development of explainable AI models

Future AI systems must provide transparent, interpretable explanations for their predictions and recommendations. Research should focus on developing inherently interpretable model architectures, improving post-hoc explanation techniques, and establishing standards for what constitutes adequate explanation in clinical contexts. Hybrid approaches that combine interpretable models with deep learning components may offer optimal trade-offs between performance and explainability.

9.2 Prospective validation and implementation research

Randomized controlled trials comparing AI-assisted care with standard practice are essential for demonstrating clinical utility. Beyond efficacy trials, implementation science research examining real-world adoption barriers, user acceptance, workflow integration, and long-term sustainability will inform successful deployment strategies. Pragmatic trial designs that allow for model updates and adaptation during the study period may better reflect real-world conditions than traditional RCT designs.

10. Regulatory and Ethical Considerations

The deployment of AI in healthcare raises complex regulatory and ethical questions that must be addressed through thoughtful policy development, stakeholder engagement, and ongoing dialogue.

10.1 Regulatory frameworks for adaptive AI

Traditional regulatory pathways assume that medical devices remain static after approval. AI systems that continuously learn and adapt challenge this assumption, requiring new frameworks that allow for iterative improvement while maintaining safety and efficacy standards. The FDA's proposed approach for predetermined change control plans (PCCPs) represents one model, allowing manufacturers to specify in advance how algorithms may be modified and under what conditions re-review is required. However, implementation details, including thresholds for acceptable performance drift and requirements for post-market surveillance, remain under development.

10.2 Liability and accountability

When AI systems contribute to medical decisions, questions of liability arise: Who is responsible when an AI-assisted decision results in patient harm—the clinician who relied on the recommendation, the institution that deployed the system, or the developer who created the algorithm? Legal frameworks must evolve to address these questions while preserving incentives for innovation and ensuring that patients have recourse in cases of injury. The concept of "AI as a medical device" provides one framework, but additional clarity is needed regarding the standard of care for AI-assisted decision-making.

10.3 Data privacy and security

AI systems require large datasets for training and validation, raising concerns about patient privacy and data security. While regulations such as HIPAA in the United States and GDPR in Europe provide frameworks for protecting health information, the use of data for AI development—particularly when data is shared across institutions or with commercial entities—requires careful attention to consent, de-identification, and data governance. Federated learning and differential privacy techniques offer promising approaches to enable collaborative model development while protecting individual privacy.

10.4 Informed consent and patient autonomy

Patients have the right to know when AI systems are involved in their care and to understand how these systems may influence clinical decisions. Informed consent processes should disclose AI involvement, explain its role in decision-making, and ensure that patients can opt out if they choose. The level of detail required for adequate disclosure—ranging from general notification of AI use to detailed explanations of specific algorithms—remains an area of active ethical debate.

10.5 Equity and access

As AI technologies become integral to high-quality care, ensuring equitable access becomes an ethical imperative. AI systems that require expensive infrastructure, specialized training, or proprietary data may exacerbate existing disparities between well-resourced and under-resourced healthcare settings. Policy interventions, including open-source models, infrastructure support for safety-net hospitals, and training programs for diverse healthcare workforces, will be necessary to prevent AI from widening the equity gap.

10.6 Clinical Implementation Strategies

Successful translation of AI from research to clinical practice requires deliberate implementation strategies that address technical, organizational, and human factors.

10.7 Stakeholder engagement

Early and ongoing engagement with clinicians, nurses, patients, administrators, and IT personnel is essential for understanding needs, addressing concerns, and building support for AI adoption. Co-design approaches that involve end-users throughout the development process can ensure that systems align with clinical workflows and address real-world needs.

10.8 Pilot testing and iterative refinement

Deploying AI systems initially in controlled pilot settings allows for identification and resolution of technical issues, workflow disruptions, and usability problems before widespread rollout. Iterative refinement based on user feedback and performance monitoring can improve system design and increase user acceptance.

10.9 Training and education