An Analysis of Publication Rates, Trends, and Characteristics of Retinal Detachment Trials on ClinicalTrials.gov

Article Information

Ibrahim Abboud, BS1, Aditi Chitre, BA1, Naneeta Desar, BS1, Clyde Siringoringo, BS1, Emily Ho, BS1, Marina Gad El Sayed, BS1, Kimia Rezaei, BS1, Rolando Sceptre Ganasi, BS2, Shameema Sikder, MD3, Kapil Mishra, MD2*

1University of California, Riverside, School of Medicine, Riverside, California, USA.

2University of California, Irvine, School of Medicine, Irvine, California, USA.

3Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

*Corresponding author: Kapil Mishra, MD, University of California, Irvine, School of Medicine, Irvine, California, USA.

Received: 03 January 2026; Accepted: 21 January 2026; Published: February 07, 2026.

Citation: Ibrahim Abboud, Aditi Chitre, Naneeta Desar, Clyde Siringoringo, Emily Ho, Marina Gad El Sayed, Kimia Rezaei, Rolando Sceptre Ganasi, Shameema Sikder, Kapil Mishra. An Analysis of Publication Rates, Trends, and Characteristics of Retinal Detachment Trials on ClinicalTrials.gov. Journal of Ophthalmology and Research. 9 (2026): 01-09.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Retinal detachment (RD) is a sight-threatening condition that requires timely intervention to prevent irreversible vision loss. Despite advances in surgical and pharmacologic management, the landscape of RD registered clinical trials (RCT) remains under-characterized in the literature. This study aimed to describe the characteristics, publication trends, and potential gaps in RD trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov. Methods: A comprehensive search of ClinicalTrials.gov was conducted on January 1, 2025, using keywords related to RD. Two authors independently verified study eligibility, with discrepancies resolved by a third reviewer. Data were extracted on study type, phase, sponsorship, location, population, principal investigator characteristics, and completion status. Trials completed before January 1, 2022, were analyzed for publication status and outcomes using PubMed and Google Scholar. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Results: A total of 405 RD-focused CTs were identified. Over the past two decades, RD trials increased significantly, although at a slower rate than all RCTs. RD trials were predominantly interventional (74.1%) and non-industry sponsored (85.2%). The most common study types were drug-based (44.0%) and procedural interventions (33.7%). Majority of trials were conducted internationally (p=0.0371) and focused on adults (p=0.0008). Male principal investigators led 72.6% of trials, and MD-only investigators accounted for the majority (61.2%). Among the 202 completed studies, 64.3% (p<0.003) were published, with positive outcomes significantly more likely to be reported than negative ones (84.6% vs. 15.4%, p < 0.0001). Conclusion: This study provides a comprehensive overview of RD clinical research. It illustrates the expanding global effort into this field. Less than two-thirds of the completed trials were published, with positive outcome studies significantly more represented in the published literature.

Keywords

Retinal detachment; ClinicalTrials.gov; Clinical trial characteristics; Publication trends; Clinical trial reporting; Research transparency; Ophthalmology.

Article Details

1. Introduction

Retinal detachment (RD) is a sight-threatening condition requiring timely intervention to prevent permanent vision loss. It occurs when the retina separates from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium, disrupting photoreceptor function and leading to visual impairment and potential blindness if left untreated [1]. RD significantly affects patient quality of life, limiting daily activities and increasing the burden on healthcare systems. Studies indicate vision-related quality of life is substantially impaired in patients following rhegmatogenous RD surgery [2]. While advances in surgical techniques and pharmacologic interventions have improved outcomes, optimizing treatment still necessitates rigorous clinical research and data dissemination.

Clinical trials (CTs) are essential for evaluating emerging treatments and redefining existing approaches. They contribute to developing new interventions by testing their safety and long-term outcomes in controlled settings. The range of trials currently being investigated includes the development of surgical techniques, novel biotechnological therapies, and anti-inflammatory agents. Their findings provide evidence to support such innovative treatments.

Despite the importance of novel clinical research findings, determining the scope and emphasis of these trials is essential for assessing advancements in the field and highlighting areas with minimal knowledge. In response to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Modernization Act of 1997, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) established ClinicalTrials.gov in 2000 as a public registry designed to provide information on ongoing and completed clinical studies, including study results, to support participant awareness and inform future research [3]. Existing studies on publication rates in ophthalmic subspecialties, such as glaucoma, diabetic macular edema, age-related macular degeneration, corneal diseases, and strabismus, have investigated patterns in trial phase, sponsorship, geographic distribution, type of intervention, and publication of results [4-7]. These comprehensive analyses have helped shape pathways and provided insights into the productivity of research.

To the best of our knowledge, no comparable systematic reviews of RD trials have been done. This study seeks to close this gap by offering a thorough descriptive examination of RD clinical studies listed on ClinicalTrials.gov, mapping out their characteristics and identifying potential trends. Our findings may inform policies to improve trial registration, reporting, and accessibility, ultimately supporting more comprehensive and reliable evidence for RD management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Identification, Eligibility, and Temporal Trend Assessment

We identified RCTs from ClinicalTrials.gov (accessed on January 01, 2025) with no time restriction using keywords related to RD, including: "retinal detachment", "separation of the neurosensory retina", "retinal break", "retinal tear", "retinal hole", "posterior vitreous detachment" (PVD), "vitreoretinal traction", "retinal pigment epithelium detachment", "lattice degeneration", "proliferative vitreoretinopathy" (PVR), "retinoschisis" or "retinal dialysis". Two authors independently confirmed whether the study is on RD, with a third author resolving disputes. This study used publicly available, deidentified data from ClinicalTrials.gov and did not involve human subjects, human tissue, or patient-level identifiable information. Therefore, this study was exempt from University of California, Irvine Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Ethics Committee, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional policies.

To compare the temporal trend of registered RD trials with all ClinicalTrials.gov–registered trials over the past two decades, annual counts of newly registered studies from 2004 through 2024 were extracted from ClinicalTrials.gov. For comparability, annual study counts were indexed to the 2004 baseline year (index = 100), with subsequent years expressed as relative changes compared with baseline.

2.2. Study Characteristics and Data Extraction

For each eligible RCT, we extracted the study characteristics, including category, phase, location, funding, gender, education of the principal investigator (PI), enrollment number, and months to completion. Following a similar methodology to Cehelyk [5], we categorized trials according to these guidelines: 1) An industry-sponsored trial has at least one industry organization as a sponsor. 2) Trials were classified as early phase if they were in phase 1 or the uncategorized phase, and late phase if they were in phase 1/2, phase 2, phase 2/3, phase 3, or phase 4. 3) Studies conducted with a principal investigator's location in the United States were deemed domestic; otherwise, they were considered international.

2.3. Assessment of Publication Status and Study Outcomes

To allow adequate time for a CT to publish its results, a trial’s completion date was set (January 1, 2022) to allow three years for results to be published before our analysis. The process of verifying a publication status was performed through a four-step method [5], First, the National Clinical Trial (NCT) number for each study was searched in PubMed.gov and Google Scholar. Second, the corresponding ClinicalTrials.gov record was reviewed to identify any associated or linked publications. Third, the publicly listed study title was searched in both PubMed and Google Scholar. Finally, the official study title, when different from the brief trial title, was searched in these databases to identify the publications. We defined a positive study if its publication reported statistically significant results that aligned with the trial’s main hypothesis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed using two-tailed chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests where appropriate, and continuous variables were analyzed using two-tailed t-tests. Temporal trends in indexed annual study counts were evaluated using linear regression, with the slope of the fitted line representing the year-to-year (YoY) percent change in trial registrations. Differences in growth rates between RD trials and all ClinicalTrials.gov–registered trials were assessed by comparing regression slopes. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05, and analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 365.

3. Results

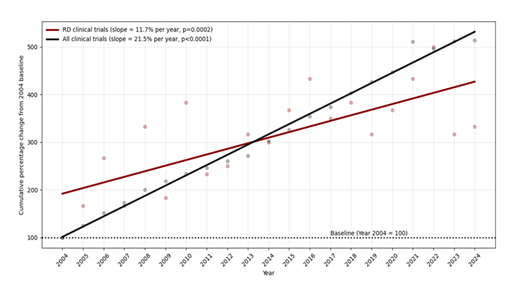

The analysis, after screening for RD-focused trials, consisted of 405 trials. Temporal trend analysis demonstrated a significant year-to-year increase in RD clinical trial registrations over the past two decades (slope representing % YoY change = 11.7%; p=0.0002). In comparison, all ClinicalTrials.gov-registered trials exhibited a steeper growth trajectory (slope = 21.5%; p<0.0001), with the difference in growth rates between RD trials and all clinical trials reaching statistical significance (p = 0.0002) (Figure 1).

3.1. Characteristics of RD trials (Category, Phase, Location, Subjects, Funding):

The majority of RD trials were interventional trials (74.1%). Within the interventional category, trials were primarily more focused on drug-based interventions (44.0%), followed by procedures (33.7%), devices (13%), biologics (3.0%), and other interventions (6.3%). Early-phase interventional trials were more common compared to the Late-phase interventional trials (58.3% vs 41.7%, p<0.0001). Assessing the studies' populations, the majority of trials focused on adults only (78.3%), followed by those that included both adults and pediatrics (17.0%), and lastly, those that exclusively included pediatric subjects (4.7%). In comparison to observational trials, interventional trials had a higher focus on adults-only or pediatrics-only subjects (p = 0.0008). 14.8% of all trials had industry funding, and there was no significant difference in funding between observational trials (13.3%) and interventional trials (15.3%) (p=0.6195) (Table 1).

Table 1. Overall Characteristics of Analyzed Retinal Detachment Clinical Trials.

|

Overall Characteristics of Analyzed Retinal Detachment Trials |

|||||||

|

Variable |

All Trials (%) |

Interventional (%) |

Observational (%) |

P-Value |

Published (%) |

Non- Published (%) |

P-Value |

|

Total |

405 (100) |

300 (100) |

105 (100) |

130 (100) |

72 (100) |

||

|

Study Type |

|||||||

|

Interventional |

300 (74.1) |

86 (66.1) |

49 (68.1) |

0.3634 |

|||

|

Observational |

105 (25.9) |

44 (33.9) |

23 (31.9) |

||||

|

Interventional Category |

|||||||

|

Biologic |

9 (2.2) |

9 (3.0) |

1 (0.8) |

0 (0.0) |

0.195 . |

||

|

Device |

39 (9.6) |

39 (13.0) |

7 (5.4) |

11 (15.3) |

|||

|

Drug |

132 (32.6) |

132 (44.0) |

41 (31.5) |

20 (27.8) |

|||

|

Procedure |

101 (24.9) |

101 (33.7) |

32 (24.6) |

15 (20.8) |

|||

|

Other |

19 (4.7) |

19 (6.3) |

5 (3.9) |

3 (4.2) |

|||

|

Phase |

|||||||

|

Early Phase or Uncategorized* |

280 (69.1) |

175 (58.3) |

105 (100) |

<0.0001 |

92 (70.8) |

52 (72.2) |

0.8269 . |

|

Late Phase** |

125 (30.9) |

125 (41.7) |

0 |

38 (29.2) |

20 (27.8) |

||

|

Location |

|||||||

|

Domestic |

100 (24.7) |

82 (27.3) |

18 (17.1) |

0.0371 |

29 (22.3) |

19 (26.4) |

0.5139 . |

|

International |

305 (75.3) |

218 (72.7) |

87 (82.9) |

101 (77.7) |

53 (73.6) |

||

|

Age Focus of Trial |

|||||||

|

Children Only |

19 (4.7) |

18 (6.0) |

1 (1.0) |

0.0008 |

7 (5.4) |

1 (1.4) |

0.2363 . |

|

Children and Adults |

69 (17.0) |

40 (13.3) |

29 (27.6) |

26 (20.0) |

11 (15.3) |

||

|

Adult Only |

317 (78.3) |

242 (80.7) |

75 (71.4) |

97 (74.6) |

60 (83.3) |

||

|

Sponsorship (Funding) |

|||||||

|

Industry |

60 (14.8) |

46 (15.3) |

14 (13.3) |

0.6195 |

13 (10.0) |

15 (20.8) |

0.0328 . |

|

Non-Industry |

345 (85.2) |

254 (84.7) |

91 (86.7) |

117 (90.0) |

57 (79.2) |

||

|

Principal Investigator Gender |

|||||||

|

Male |

294 (72.6) |

210 (70.0) |

85 (80.9) |

0.0298 |

100 (76.9) |

51 (70.8) |

0.3399 . |

|

Female |

111 (27.4) |

90 (30.0) |

20 (19.1) |

30 (23.1) |

21 (29.2) |

||

|

Principal Investigator Education |

|||||||

|

MD Only |

248 (61.2) |

188 (62.7) |

60 (57.1) |

0.622 |

91 (70.0) |

41 (56.9) |

0.3606 . |

|

PhD Only |

37 (9.1) |

28 (9.3) |

9 (8.6) |

10 (7.7) |

5 (6.9) |

||

|

MD/PhD |

61 (15.1) |

44 (14.7) |

17 (16.2) |

26 (20.0) |

6 (8.4) |

||

|

Other/Unknown |

59 (14.6) |

40 (13.3) |

19 (18.1) |

3 (2.3) |

20 (27.8) |

||

|

Status (As of January 01, 2025) |

|||||||

|

Completed |

263 (64.9) |

179 (59.7) |

84 (80.0) |

0.0006 |

|||

|

Not Completed (Active) |

100 (24.7) |

83 (27.7) |

17 (16.2) |

||||

|

Withdrawn/Terminated |

42 (10.4) |

38 (12.7) |

4 (3.8) |

||||

|

Average Enrollment Number of Completed Trials |

|||||||

|

Total |

1029 |

76 |

3061 |

0.0289 |

870 |

1280 |

0.7548 |

|

Domestic |

2189 |

89 |

9295 |

0.061 |

3520 |

72 |

0.4216 |

|

International |

708 |

71 |

1920 |

0.1316 |

134 |

1613 |

0.2166 |

|

Average Months for Completion of Completed Trials |

|||||||

|

Months, study start date to Primary Completion † |

29.19 (± 28.45) |

27.76 (± 21.13) |

32.21 (± 39.69) |

0.2378 |

30.63 (± 27.67) |

29.96 (± 34.52) |

0.8786 |

|

Months, study start date to Final Completion ‡ |

31.99 (± 29.29) |

30.81 (± 22.12) |

34.48 (± 40.50) |

0.3455 |

33.64 (± 28.26) |

31.68 (± 35.26) |

0.6657 |

*Early Phase or Uncategorized: Phase 1 trial or uncategorized

**Late Phase: Phase 2/3, Phase 3, and Phase 4 trials.

† Primary completion: last primary outcome datapoint collection completed.

‡ Final completion: all datapoints collected.

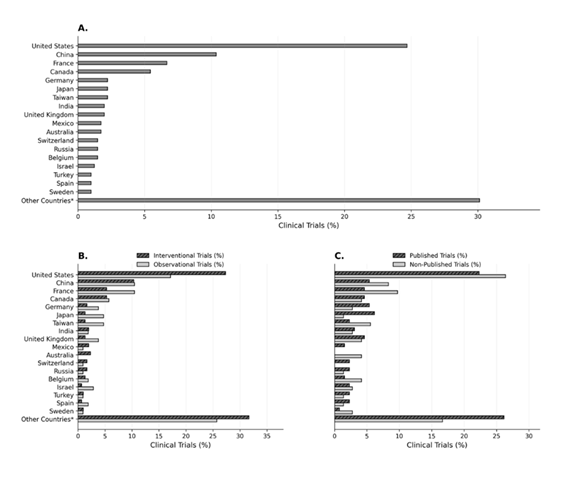

By comparing domestic versus international studies, the majority of both interventional and observational trials were performed internationally (72.7% vs. 27.3% for interventional and 82.9% vs. 17.1% for observational, p = 0.0371) (Table 1). However, when analyzed by individual countries, the United States was the leading nation (24.7%), followed by China (10.4%), France (6.7%), Canada (5.4%), then Germany, Japan, and Taiwan (2.2%) (Figure 2).

3.2. Principal Investigator (PI), Trial Status, and Enrollment:

Male PIs led the majority of trials compared to Female PIs (70.0% vs. 30.0% for interventional and 80.9% vs. 19.1% for observational, p = 0.0298). Factoring in the PIs’ education, the majority of studies were led by MD-only investigators (61.2%), followed by MD/PhD (15.1%), PhD-only (9.1%), and other degrees (14.6%).

Out of the 405 studies, 263 (64.9%) were completed, 100 (24.7%) remained active, and 42 (10.4%) were withdrawn or terminated. With statistical significance (p = 0.0006), observational studies showed a greater completion rate than interventional (80.0% vs. 59.7%) and a lower withdrawal rate (3.8% vs. 13.67%). In comparison to interventional trials, enrollment numbers were significantly higher in observational studies {3061 vs 76}. Moreover, the average completion time was 30.81 months for interventional trials and 34.48 months for observational trials (Table 1).

3.3. Publication Status and Study Outcomes:

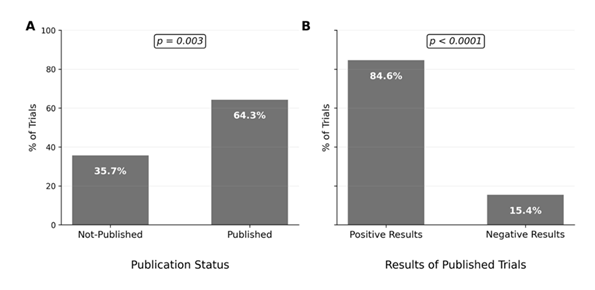

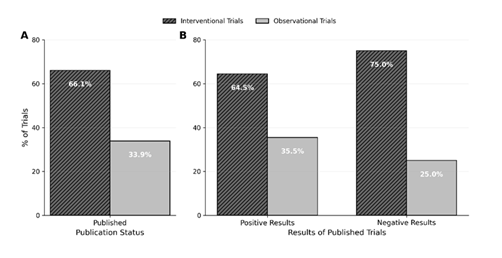

Among the 202 trials completed before the set completion date (January 01, 2022), 130 (64.3%) studies were published (p=0.003), with a significant majority reporting positive results compared to negative results (84.6% vs 15.4%, p< 0.0001) (Figure 3). Interventional trials were published more often than observational trials (66.1% vs. 33.9%) among the completed and published studies (Figure 4), with drug-based trials having the greatest publication rate (31.5%). Trials conducted internationally accounted for the majority of published trials (77.7%), and their publication rate was slightly higher compared to domestic trials (65.58% vs. 60.42%). 90.0% of published trials were non-industry sponsored (p = 0.0328) with a greater publishing rate compared to industry-sponsored trials (67.24% vs 46.43%). Among principal investigators, male-led trials (76.9%) were published more frequently than female-led studies (23.1%), and the highest publishing rate was achieved by MD-only investigators (70.0%) when compared to those headed by PhD, MD/PhD, or other degrees (Table 1).

4. Discussion

The findings of this study provide a comprehensive overview of RD trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov. Over the past two decades, RD trial registrations increased significantly, though at a slower rate than the overall clinical trial landscape. Most RD trials were interventional, early phase, adult-focused, and predominantly non-industry sponsored. Observational studies demonstrated higher completion rates and larger enrollment than interventional trials. Among completed trials, approximately two-thirds were published, with published studies more frequently reporting positive outcomes.

Although retinal diseases account for the highest number of ophthalmic RCTs [8], RD trial growth remains modest compared with overall RCT expansion, likely reflecting surgical complexity and recruitment challenges. The predominance of interventional trials highlights ongoing innovation in pharmacologic and surgical reattachment strategies and the need for research in neuroprotection, retinal biology, and minimally invasive techniques [9-11] and, the high proportion of early-phase trials suggests continued exploration of novel therapies and challenges in trial advancement.

From an epidemiological perspective, RD represents a major cause of vision loss, with an annual incidence of [12] 17 per 100,000 [12]. Although the United States is the leading nation in the RD clinical field, our study and prior literature have pointed out the increasing RCT activity in East Asia, specifically China [13]. The burden of RD and the widespread interest in RD research are demonstrated by the geographic distribution of RCTs conducted internationally. Given the growing incidence of RD and the variety of clinical manifestations, multicenter trials are critical for guiding optimal therapies.

Observational studies showed higher completion, lower withdrawal, and greater enrollment than interventional trials, reflecting simpler designs, lower risk, fewer eligibility barriers, and reduced funding needs [14,15]. With most RD trials were non-industry funded by academic and public sources, it indicates the sustained governmental support for retinal research, including initiatives such as the National Eye Institute Audacious Goals Initiative [16]. Additionally, our study highlights that among the completed trials, 64.3% reached publication. This pattern is on par with previously identified trends in clinical ophthalmic research. Approximately 81% of completed ophthalmology RCTs have not been published [17]. RD publication rates were comparable to age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema (~67%) [18], higher than (51.9%)5 and strabismus (59%) [7], but remained moderate relative to other fields, including oncology (72.5%) [19], cardiology (56%) [20] and neurology (46%) [21]. Despite this satisfactory publication rate, one-third of RD trials remain unpublished beyond expected timelines. Although delays may reflect ongoing analysis or peer review, most studies are published within two years, making a three-year window is an appropriate benchmark for evaluating publication activity [22]. Among those published RD trials, 84.6% reported positive primary outcomes, consistent with prior literature showing preferential publication of positive findings [23,24]. Similar patterns are seen in cataract trials, where positive studies were published more often than negative ones [25]. While multiple factors may contribute to this pattern, this descriptive data helps characterize RD trial dissemination and captures current research practices and outcomes.

This study found that both interventional and observational RD trials were predominantly led by male PIs, reflecting persistent gender disparities in clinical trial leadership. This aligns with broader evidence showing that women comprise only about one-third of clinical trial PIs [26,27], with ophthalmology among the lowest-represented specialties. Contributing factors include the low proportion of women in vitreoretinal surgery, fewer women in senior academic and funded leadership roles, disparities in authorship, and longer peer-review timelines [28-30]. Together, these multifactorial barriers identify the need for initiatives to promote gender equity in research leadership. Furthermore, MD-only investigators led most RD trials (61.2%), exceeding MD-PhD, PhD-only, and other degree holders, consistent with broader trends showing MDs more frequently lead clinical research [31,32]. This likely reflects institutional emphasis on physician-led studies and the surgical nature of RD, which requires licensed surgeons to serve as PIs.

Although this study provides insight into RD trial publication trends, several limitations warrant consideration. Reliance on ClinicalTrials.gov may have excluded trials registered in other databases. Some trials classified as unpublished may still be undergoing manuscript preparation, potentially underestimating publication rates. Linking trials to publications is challenging due to inconsistent reporting of registry identifiers (e.g., NCT numbers) [33], with only a minority of studies including direct registry-publication links and many requiring manual matching because of title changes or author name variations [34-36]. Additionally, this analysis focused on peer-reviewed journal publications and did not capture alternative dissemination formats, such as conference abstracts, preprints, or registry-posted results, which may still contribute to knowledge dissemination [37].

To further explore the barriers to publication rates, future research should explore barriers to trial publication using qualitative approaches, such as investigator surveys, to assess logistical challenges, time constraints, perceived impact, and journal acceptance [37]. Longitudinal analyses could evaluate publication trends over time, particularly in light of increased FDA enforcement and WHO reporting recommendations of a 12-month deadline for registry reporting and a 24-month deadline for journal publication [38,39]. Additionally, exploring innovative dissemination strategies (centralized trial result repositories or automated registry-publication linking) may help reduce reporting delays [21] and strengthen the evidence base for RD management and clinical decision-making.

5. Conclusion

This study characterizes the design, distribution, and reporting patterns of RD trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov. Approximately two-thirds of completed trials were published, with positive findings reported more frequently than negative ones. These results offer a descriptive overview of current research activity and may help inform future efforts to support consistent reporting and evidence generation in retinal detachment clinical research.

List of Abbreviations

RD (retinal detachment), CT (clinical trial), PI (principal investigator), MD (Doctor of Medicine), PhD (Doctor of Philosophy), PVD (posterior vitreous detachment), PVR (proliferative vitreoretinopathy), RPE (retinal pigment epithelium), IRB (Institutional Review Board), NCT (National Clinical Trial identifier), FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration), and WHO (World Health Organization).

Statements and Declarations

- Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge support to the Gavin Herbert Eye Institute at the University of California, Irvine from an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness. The authors thank Swaroop Vedula, MBBS, MPH, PhD, for his guidance and feedback during the development of this study. All individuals acknowledged have provided permission to be included in this section.

- Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

- Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

- Ethics approval and consent to participate: This study used publicly available, deidentified data from ClinicalTrials.gov and did not involve human subjects, human tissue, or patient-level identifiable information. Therefore, approval from an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Ethics Committee was not required, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional policies.

- Availability of data and materials: Data was extracted from publicly available, deidentified using ClinicalTrials.gov. The data analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Authors' contributions: IA contributed to data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision for important intellectual content, and statistical analysis. AC, ND, CS, EH, MG, KR, and RG each participated in data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript revision. SS and KM, as supervising principal investigators, jointly contributed to study oversight, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript, statistical guidance, and provision of technical or material support. KM additionally contributed to project administration and study design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Abdelhady A, Gaughan J, Schorr C, et al. The Prevalence of Retinal Detachment and Associated Comorbidities over a 5-year Period. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 62 (2021): 3080.

- Smretschnig E, Falkner-Radler CI, Binder S, et al. Vision-Related Quality of Life And Visual Function After Retinal Detachment Surgery. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.) 36 (2016) : 967-973.

- About ClinicalTrials.gov | ClinicalTrials.gov (2024).

- Meller LLT, Kashaf MS, Sambo A, et al. Publication Rates and Patterns of Registered Glaucoma Trials. Ophthalmology 132 (2025): 1054-1061.

- Cehelyk EK, Crespo MA, Syed ZA, et al. Publication Rates of Registered Corneal Trials on ClinicalTrials.gov. Cornea 43 (2024) : 356.

- Hughes PJ, Polo RN, Fine HF, et al. Publication Rates of Registered Clinical Trials in Diabetic Macular Edema (2020).

- Meller L, Sambo AB, Nguyen N, et al. Publication rates of registered strabismus trials from ClinicalTrials.gov. Journal of AAPOS: The Official Publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus 28 (2024): 103936.

- AlRyalat SA, Abukahel A, Elubous KA. Randomized controlled trials in ophthalmology: A bibliometric study. F1000Research 8 (2019): 1718.

- Wubben TJ, Besirli CG, Zacks DN, et al. Pharmacotherapies for Retinal Detachment. Ophthalmology 123 (2016): 1553-1562.

- Kunikata H, Abe T, Nakazawa T, et al. Historical, Current and Future Approaches to Surgery for Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine 248 (2019): 159-168.

- Sodhi A, Leung L-S, Do DV, et al. Recent trends in the management of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Survey of Ophthalmology 53 (2008): 50-67.

- Ge JY, Teo ZL, Chee ML, et al. International incidence and temporal trends for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Survey of Ophthalmology 69 (2024): 330-336.

- Lee EH, Lee S, Shin JI, et al. Registered clinical trial trends evolved differently in East Asia vs the United States during 2014-2023. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 183 (2025): 111791.

- Thiese MS. Observational and interventional study design types; an overview. Biochemia Medica 24 (2014): 199-210.

- Newman AB, Avilés-Santa ML, Anderson G, et al. Embedding clinical interventions into observational studies. Contemporary Clinical Trials 46 (2016): 100-105.

- Audacious Goals Initiative | National Eye Institute (2025).

- Yilmaz T, Gallagher MJ, Cordero-Coma M, et al. Discontinuation and nonpublication of interventional clinical trials conducted in ophthalmology. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology 55 (2020): 71-75.

- Patel S, Sternberg P, Kim SJ, et al. Publishing of Results from Ophthalmology Trials Registered on ClinicalTrials.gov. Ophthalmology Retina 4 (2020): 754-755.

- Chapman PB, Liu NJ, Zhou Q, et al. Time to publication of oncology trials and why some trials are never published. PLoS ONE 12 (2017): e0184025.

- Psotka MA, Latta F, Cani D, et al. Publication Rates of Heart Failure Clinical Trials Remain Low. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 75 (2020): 3151-3161.

- Sreekrishnan A, Mampre D, Ormseth C, et al. Publication and Dissemination of Results in Clinical Trials of Neurology. JAMA Neurology 75 (2018): 890-891.

- Ross JS, Mocanu M, Lampropulos JF, et al. Time to Publication Among Completed Clinical Trials. JAMA Internal Medicine 173 (2013): 825-828.

- Ioannidis JPA. Why Most Published Research Findings Are False. PLOS Medicine, 2 (2005): e124.

- Duyx B, Urlings MJE, Swaen GMH, et al. Scientific citations favor positive results: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 88 (2017): 92-101.

- Paturu T, Shukla A, Shivan SG, at al. Publication bias in clinical trials in cataract therapies: Implications for evidence-based decision-making. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery 50 (2024): 1180-1183.

- Cevik M, Haque SA, Manne-Goehler J, et al. Gender disparities in coronavirus disease 2019 clinical trial leadership. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 27 (2021): 1007-1010.

- Waldhorn I, Dekel A, Morozov A, et al. Trends in Women’s Leadership of Oncology Clinical Trials. Frontiers in Oncology 12 (2022).

- Oncel D, Syal S, Oncel D, et al. Gender Disparities Among Academic Vitreoretinal Specialists in the United States With Regard to Scholarly Impact and Academic Rank. Cureus 15 (2023): e39936.

- Giannakakos VP, Syed M, Culican SM, et al. The status of women in academic ophthalmology: Authorship of papers, presentations, and academic promotions. Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology 52 (2024), 137-147.

- Jiménez-García M, Buruklar H, Consejo A, et al. Influence of Author’s Gender on the Peer-Review Process in Vision Science. American Journal of Ophthalmology 240 (2022): 115-124.

- Hall AK, Mills SL, Lund PK. Clinician-Investigator Training and the Need to Pilot New Approaches to Recruiting and Retaining This Workforce. Academic Medicine:, Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 92 (2017): 1382-1389.

- Dickler HB, Fang D, Heinig SJ, et al. New Physician-Investigators Receiving National Institutes of Health Research Project GrantsA Historical Perspective on the “Endangered Species.” JAMA 297 (2007): 2496-2501.

- Liu S, Bourgeois FT, Dunn AG, et al. Identifying unreported links between ClinicalTrials.gov trial registrations and their published results. Research Synthesis Methods 13 (2022): 342-352.

- Bashir R, Bourgeois FT, Dunn AG. A systematic review of the processes used to link clinical trial registrations to their published results. Systematic Reviews 6 (2017): 123.

- Huser V, Cimino JJ. Linking ClinicalTrials.gov and PubMed to track results of interventional human clinical trials. PloS One 8 (2013): e68409.

- Sun LW, Lee DJ, Collins JA, et al. Assessment of Consistency Between Peer-Reviewed Publications and Clinical Trial Registries. JAMA Ophthalmology 137 (2019): 552-556.

- Song F, Loke Y, Hooper L. Why Are Medical and Health-Related Studies Not Being Published? A Systematic Review of Reasons Given by Investigators. PLOS ONE 9 (2014): e110418.

- Woodcock J. FDA Takes Action For Failure to Submit Required Clinical Trial Results Information to ClinicalTrials.Gov (2021).

- World Health Organization. Joint statement on public disclosure of results from clinical trials (2021).