An Additional, Complementary Mechanism of Action for Folic Acid in the Treatment of Megaloblastic Anemia

Article Information

Bruce K. Kowiatek

The Wellness Pharmacy, Winchester, Virginia, USA

*Corresponding Author: Bruce K. Kowiatek, The Wellness Pharmacy, 110 Highpointe Court, Winchester, Virginia 22602, USA

Received: 13 November 2018; Accepted: 20 November 2018; Published: 22 November 2018

Citation:

Bruce K. Kowiatek. An Additional, Complementary Mechanism of Action for Folic Acid in the Treatment of Megaloblastic Anemia. Journal of Biotechnology and Biomedicine 1 (2018): 021-027.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Administration of supplemental folic acid addresses the impaired DNA synthesis causing megaloblastic anemia; however, despite the possibility of high doses of folic acid-5 to 15 milligrams (mg) daily for up to four months-the extremely rapid initial onset of action-30 to 60 minutes-when administered orally is not in keeping with the accepted mechanism, which can take up to nearly 22 hours, even under enzymatic control. This would suggest an additional, complementary non-enzymatic mechanism of nucleotide methylation at work; it is, therefore, proposed here, with in vitro evidence put forth, that rapid, non-enzymatic methylation by folic acid, via 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate and 7,8-tetrahydrofolate intermediates, of deoxyuridine monophosphate to form thymidylate using the cell membrane phospholipid phosphatidylcholine as a methyl donor, leaving de-methylated phosphatidylethanolamine, is a viable additional and complementary mechanism in helping reduce megaloblastic red blood cells to normal size and function.

Keywords

Folic acid, DNA, Megaloblastic anemia, Deoxyuridine monophosphate, Thymidylate

Folic acid articles Folic acid Research articles Folic acid review articles Folic acid PubMed articles Folic acid PubMed Central articles Folic acid 2023 articles Folic acid 2024 articles Folic acid Scopus articles Folic acid impact factor journals Folic acid Scopus journals Folic acid PubMed journals Folic acid medical journals Folic acid free journals Folic acid best journals Folic acid top journals Folic acid free medical journals Folic acid famous journals Folic acid Google Scholar indexed journals DNA articles DNA Research articles DNA review articles DNA PubMed articles DNA PubMed Central articles DNA 2023 articles DNA 2024 articles DNA Scopus articles DNA impact factor journals DNA Scopus journals DNA PubMed journals DNA medical journals DNA free journals DNA best journals DNA top journals DNA free medical journals DNA famous journals DNA Google Scholar indexed journals Megaloblastic anemia articles Megaloblastic anemia Research articles Megaloblastic anemia review articles Megaloblastic anemia PubMed articles Megaloblastic anemia PubMed Central articles Megaloblastic anemia 2023 articles Megaloblastic anemia 2024 articles Megaloblastic anemia Scopus articles Megaloblastic anemia impact factor journals Megaloblastic anemia Scopus journals Megaloblastic anemia PubMed journals Megaloblastic anemia medical journals Megaloblastic anemia free journals Megaloblastic anemia best journals Megaloblastic anemia top journals Megaloblastic anemia free medical journals Megaloblastic anemia famous journals Megaloblastic anemia Google Scholar indexed journals Deoxyuridine monophosphate articles Deoxyuridine monophosphate Research articles Deoxyuridine monophosphate review articles Deoxyuridine monophosphate PubMed articles Deoxyuridine monophosphate PubMed Central articles Deoxyuridine monophosphate 2023 articles Deoxyuridine monophosphate 2024 articles Deoxyuridine monophosphate Scopus articles Deoxyuridine monophosphate impact factor journals Deoxyuridine monophosphate Scopus journals Deoxyuridine monophosphate PubMed journals Deoxyuridine monophosphate medical journals Deoxyuridine monophosphate free journals Deoxyuridine monophosphate best journals Deoxyuridine monophosphate top journals Deoxyuridine monophosphate free medical journals Deoxyuridine monophosphate famous journals Deoxyuridine monophosphate Google Scholar indexed journals Thymidylate articles Thymidylate Research articles Thymidylate review articles Thymidylate PubMed articles Thymidylate PubMed Central articles Thymidylate 2023 articles Thymidylate 2024 articles Thymidylate Scopus articles Thymidylate impact factor journals Thymidylate Scopus journals Thymidylate PubMed journals Thymidylate medical journals Thymidylate free journals Thymidylate best journals Thymidylate top journals Thymidylate free medical journals Thymidylate famous journals Thymidylate Google Scholar indexed journals red blood cells articles red blood cells Research articles red blood cells review articles red blood cells PubMed articles red blood cells PubMed Central articles red blood cells 2023 articles red blood cells 2024 articles red blood cells Scopus articles red blood cells impact factor journals red blood cells Scopus journals red blood cells PubMed journals red blood cells medical journals red blood cells free journals red blood cells best journals red blood cells top journals red blood cells free medical journals red blood cells famous journals red blood cells Google Scholar indexed journals Tetrahydrofolate articles Tetrahydrofolate Research articles Tetrahydrofolate review articles Tetrahydrofolate PubMed articles Tetrahydrofolate PubMed Central articles Tetrahydrofolate 2023 articles Tetrahydrofolate 2024 articles Tetrahydrofolate Scopus articles Tetrahydrofolate impact factor journals Tetrahydrofolate Scopus journals Tetrahydrofolate PubMed journals Tetrahydrofolate medical journals Tetrahydrofolate free journals Tetrahydrofolate best journals Tetrahydrofolate top journals Tetrahydrofolate free medical journals Tetrahydrofolate famous journals Tetrahydrofolate Google Scholar indexed journals Gas Chromatography articles Gas Chromatography Research articles Gas Chromatography review articles Gas Chromatography PubMed articles Gas Chromatography PubMed Central articles Gas Chromatography 2023 articles Gas Chromatography 2024 articles Gas Chromatography Scopus articles Gas Chromatography impact factor journals Gas Chromatography Scopus journals Gas Chromatography PubMed journals Gas Chromatography medical journals Gas Chromatography free journals Gas Chromatography best journals Gas Chromatography top journals Gas Chromatography free medical journals Gas Chromatography famous journals Gas Chromatography Google Scholar indexed journals folic acid articles folic acid Research articles folic acid review articles folic acid PubMed articles folic acid PubMed Central articles folic acid 2023 articles folic acid 2024 articles folic acid Scopus articles folic acid impact factor journals folic acid Scopus journals folic acid PubMed journals folic acid medical journals folic acid free journals folic acid best journals folic acid top journals folic acid free medical journals folic acid famous journals folic acid Google Scholar indexed journals Spectrometry articles Spectrometry Research articles Spectrometry review articles Spectrometry PubMed articles Spectrometry PubMed Central articles Spectrometry 2023 articles Spectrometry 2024 articles Spectrometry Scopus articles Spectrometry impact factor journals Spectrometry Scopus journals Spectrometry PubMed journals Spectrometry medical journals Spectrometry free journals Spectrometry best journals Spectrometry top journals Spectrometry free medical journals Spectrometry famous journals Spectrometry Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

Abbreviations:

DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; DHFR: Dihydrofolate Reductase; NADH and NAD+: Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (reduced and oxidized forms, respectively); THF: Tetrahydrofolate

1. Introduction

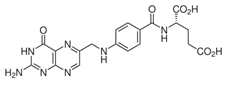

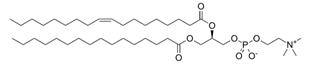

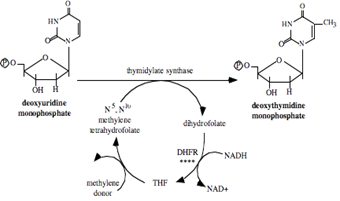

Dietary deficiency of the vitamin enzyme cofactor folic acid (Figure 1) has serious effects upon human health, including chromosome breaks, birth defects such as neural tube defects, increased risk of colon cancer, brain dysfunction, and heart disease [1]. Its deficiency is also the cause of megaloblastic anemia, or megaloblastosis, an anemic blood disorder characterized by larger-than-normal red blood cells (RBCs), or megaloblasts [2]. Two hallmarks of megaloblasts are, first, elevated levels of the cell membrane phospholipid phosphatidylcholine (PC) [3] (Figure 2) and, second, increased amounts of the nucleotide deoxyuridine 5?-monophosphate (dUMP), which is otherwise usually methylated by the folic acid derivatives 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate and 7,8-dihydrofolate, via the thymidylate synthase enzyme pathway, which also includes the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), the coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide in both its reduced and oxidized forms (NADH and NAD+, respectively), and the folic acid derivative tetrahydrofolate (THF), to deoxythymidine 5?-monophosphate (dTMP), or thymidylate, as part of normal deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) synthesis [4] (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Folic acid.

Figure 2: Phosphatidylcholine (PC).

Figure 3: Thymidylate synthase pathway.

DHFR: Dihydrofolate Reductase; NADH and NAD+: Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (reduced and oxidized forms, respectively); THF: Tetrahydrofolate.

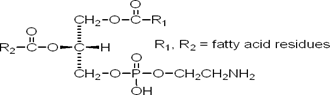

Administration of supplemental folic acid addresses the impaired DNA synthesis causing megaloblastosis; however, despite the possibility of high doses of folic acid-5 to 15 milligrams (mg) daily for up to four months-the extremely rapid initial onset of action-30 to 60 minutes-when administered orally [5] is not in keeping with this accepted mechanism, which can take up to nearly 22 hours, even under enzymatic control [6]. This would suggest an additional, complementary non-enzymatic mechanism of nucleotide methylation at work. Such non-enzymatic methylation of nucleotides has been observed previously in vitro with the metabolite cofactor S-adenosylmethionine (SAM-e) [7]; it is, therefore, proposed here, with in vitro evidence put forth, that rapid, non-enzymatic methylation by folic acid, via 5,10-methylenetetrahydofolate and 7,8-dihydrofolate intermediates, of dUMP to form thymidylate using PC as a methyl donor, leaving the de-methylated cell membrane phospholipid phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) (Figure 4), is a viable additional and complementary mechanism in helping reduce megalobastic RBCs to normal size and function.

Figure 4: Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE).

2. Experimental

All research was conducted at The Wellness Pharmacy in Winchester, VA, USA from February of 2018 through March of 2018. All sterile manipulations were performed using aseptic technique [8] in a NUAIRE Biological Safety Cabinet Class II Type A/B3 laminar flow hood. All pH measurements were made using a Horiba TwinpH waterproof B-213 Compact pH Meter. All Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) data was obtained using a Hewlett Packard 5890 Series II Gas Chromatograph. Compounds were identified as the trimethylsilyl (TMS) derivatives by using the agreement of the retention times with those of standards as the criterion for identification and the following ions for determination: m/z 321.0488 for thymidylate [9], and m/z 255.13 for PE [10]. All in-laboratory photography was obtained using a Casio EX-Z57 digital camera. All Pyrex glassware was sterilized at 130° C for one hour [11] via autoclave using a Quincy Lab Inc. Model 30 GC Lab Oven. All chemical supplies were purchased from the Professional Compounding Centers of America (PCCA) in Houston, TX, USA.

All measurements of chemicals were standardized to 0.1 Molarity (M) ±5% using an Ohaus Analytical Plus electronic balance accurate to within ±0.0001 gram (g). Final test and control samples were obtained via filtration through a sterile 0.2 micron (µm) EPS, Inc. Medi-Dose Group Disposable Disc Filter Unit and corresponding sterile Monoject syringe. Three trials per step were performed and recorded and the data presented here represents the average of that total data. All data collected fell within a statistically acceptable ±5% (p=0.05) internal margin of variance [12] with no outliers. As a control, 25 milliliters (mL) of sterile 0.9% sodium chloride in water (normal saline (NS)), pH 7.4, was heated to 37°C and maintained, with 0.45 g of PC (95% ± 5%) added and allowed to melt uniformly throughout (Figure 5). To this was added 0.015 g of folic acid (Figure 6) and the pH adjusted first downward to 2 via titration with 0.1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl), then upward to 10 via titration with 0.1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution. The pH was then adjusted back to 7.4 via HCl.

Figure 5: Control mixture of 25 mL NS, pH 7.4, at 37°C with 0.45 g PC (95% ± 5%) melted uniformly throughout.

Figure 6: Control mixture from Figure 5 with 0.15 g folic acid added.

As a test, to a second, similarly prepared mixture at pH 7.4 and 37°C, 0.45 g of highly solubilized dUMP (95% ± 5%) was added (Figure 7), subsequent pH measured, and its contents compared to the first mixture (Figure 8). Two samples were procured from the second mixture for GC/MS analysis, one to test for the presence of thymidylate and one to test for the presence of PE.

Figure 7: Test mixture, pH 6.2, at 37°C with 0.45 g dUMP (95% ± 5%) added.

Figure 8: Comparison of test (left) and control (right) mixtures.

3. Results and Discussion

At physiologic salinity, pH, and temperature [13], no precipitation of any of the components of the control mixture was observed; furthermore, no precipitation was observed in this mixture as a function of pH within the stability range of a therapeutically relevant quantity of folic acid [14] and PC [15]. Precipitation, however, was observed in the test mixture, beginning immediately upon the addition of dUMP and reaching completion within 10 minutes after its addition. The pH of the test mixture was 6.2. Such precipitation, ruled out as a function of pH, indicated an increase in hydrophobicity, as would be the case if hydrophilic dUMP were being converted into more hydrophobic thymidylate [16]. Also, the change in appearance of the mixture from opaque to translucent indicated the conversion of PC into PE [17]. GC/MS analysis confirmed the presence of both thymidylate (Figure 9) (95% ± 5%) and PE (Figure 10) (95% ± 5%).

Figure 9: GC/MS of TMS-thymidylate (95% ± 5%) detected in test mixture. Note peak at m/z 321.0488.

Figure 10: GC/MS of TMS-PE (95% ± 5%) detected in test mixture. Note peak at m/z 255.13.

The mechanism at work here appears to be extremely rapid and non-enzymatic in nature. It most likely involves successive de-methylation of PC by folic acid to form, first, a 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate intermediate and PE, with the former then donating its methylene group to methylate dUMP into thymidylate, leaving a second, 7,8-dihydrofolate intermediate, which then quickly oxidizes back to folic acid. Such a supposition is supported by observations of these two intermediates’ formation by transient, acidic changes in pH by De Brouwer et al [18]. This transient nature, however, along with the extremely rapid rate of reaction observed in this experiment, precludes their detection here, although its inferred presence seems to best account for the observed results.

Such a rapid, non-enzymatic mechanism would also account for the quick onset of action of folic acid therapy in the treatment of megaloblastic anemia, acting in an additional and complementary fashion with that in already elucidated enzymatic mechanisms. It also establishes folic acid, alongside SAM-e, as a powerful agent involved in the non-enzymatic methylation of endogenous nucleotides.

Acknowledgements

I thank the staff of The Wellness Pharmacy for the generous use of their facility and equipment. I also especially thank my loving family for their generous gift of time in the performance of these experiments and the writing of this article. This article is dedicated to the memory of Raymond Burnell Knepp (1942-2009), founder of The Wellness Pharmacy.

References

- Sousa MM, Krokan HE, Slupphaug G. DNA-uracil and human pathology. Mol Aspects Med 28 (2007): 276-306.

- NIH: National Institutes of Health. MedlinePlus: Megaloblastic anemia (2012).

- Walletin L, Berlin R, Vikrot O. Studies on plasma lipid and phospholipid composition in pernicious anemia before and after specific treatment. Acta Med Scand 201 (1977): 161-165.

- Horton HR, Moran LA, Ochs RS, et al. Principles of biochemistry (2nd Edn.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall (1996).

- IPCS Inchem. Folic acid (1991).

- Black GE, Abramson FP. Measuring DNA synthesis rates with stable isotopes. Anal Chem 75 (2003): 56-63.

- Barrows LR, Magee PN. Nonenzymatic methylation of DNA by S-adenosylmethionine in vitro. Carcinogenesis 3 (1982): 349-351.

- ASHP guidelines on quality assurance for pharmacy-prepared sterile products. Drug distribution and control: Preparation and handling-guidelines (2010).

- MassBank Record: PR100611. Thymidine-5?-monophosphate (2011).

- MassBank Record: UT001356. Phosphatidylethanolamine (2011).

- Black J. Microbiology. Prentice Hall (1993): 334.

- Bolton S. Pharmaceutical statistics (3rd Edn.). New York: Marcel Dekker (1997).

- Seely R, Stephens T, Tate P. Anatomy and physiology (8th Edn.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill (2007).

- De Brouwer V, Zhang GF, Storozhenko S, et al. pH stability of individual folates during critical sample preparation steps in prevision of the analysis of plant folates. Photochem Anal 18 (2007): 496-508.

- Ho RJY, Schmetz M, Deamer DW. Nonenzymatic hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine prepared as liposomes and mixed micelles. Lipids 22 (1987): 156-158.

- Anandagopu P, Suhanya S, Jayaraj V, et al. Role of thymine in protein coding frames of mRNA sequences. Bioinformation 2 (2008): 304-307.

- Avanti® Polar Lipids, Inc. MSDS: L-?-phosphatidylethanolamine (E. coli) (2012).

- De Brouwer V, Zhang GF, Storozhenko S, et al. pH stability of individual folates during critical sample preparation steps in prevision of the analysis of plant folates. Photochem Anal 18 (2007): 496-508.