A Severe Episode of Hemolytic Anemia After Amoxicillin Exposure in A G6PD Deficient Patient

Article Information

Carmelo J. Blanquicett1,2, Tapasya Raavi3, Stephanie M. Robert4

1Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL, USA

2Department of Medicine, Division of General Medicine and Geriatrics, Emory University School of Medicine and Atlanta VA Medical Center, Atlanta, GA, USA

3Emory University Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA, USA

4Yale University School of Medicine, Department of Neurosurgery, New Haven, CT, USA

*Corresponding Author: Dr. Carmelo J. Blanquicett MD, PhD, Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, Department of Medicine, Division of General Medicine and Geriatrics, Emory University School of Medicine and Atlanta VA Medical Center, Atlanta, GA, USA

Received: 01 May 2019; Accepted: 08 May 2019; Published: 20 May 2019

Citation:

Carmelo J. Blanquicett, Tapasya Raavi, Stephanie M. Robert. A Severe Episode of Hemolytic Anemia After Amoxicillin Exposure in A G6PD Deficient Patient. Archives of Clinical and Medical Case Reports 3 (2019): 104-112.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency is the most common enzyme deficiency worldwide, with genetic variants resulting in a range of phenotypes that vary from asymptomatic to severe hemolysis. The G6PD deficiency A- variant is associated with hemolysis., typically due to infectious or medication exposures, particularly antimalarials and sulfonamide drugs. We report a case of severe hemolytic anemia in a G6PD deficient patient whose only known exposure was amoxicillin two weeks prior to his episode of severe hemolysis, for which he presented to our hospital. An extensive infectious and hematologic workup resulted negative, with the exception of a positive G6PD deficiency result. Although rare, we suggest that the patient’s severe hemolytic anemia is probably related to amoxicillin exposure.

Keywords

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, Hemolytic anemia, Enzyme deficiency, Amoxicillin

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase articles Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase Research articles Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase review articles Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase PubMed articles Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase PubMed Central articles Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase 2023 articles Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase 2024 articles Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase Scopus articles Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase impact factor journals Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase Scopus journals Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase PubMed journals Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase medical journals Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase free journals Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase best journals Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase top journals Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase free medical journals Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase famous journals Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase Google Scholar indexed journals Hemolytic anemia articles Hemolytic anemia Research articles Hemolytic anemia review articles Hemolytic anemia PubMed articles Hemolytic anemia PubMed Central articles Hemolytic anemia 2023 articles Hemolytic anemia 2024 articles Hemolytic anemia Scopus articles Hemolytic anemia impact factor journals Hemolytic anemia Scopus journals Hemolytic anemia PubMed journals Hemolytic anemia medical journals Hemolytic anemia free journals Hemolytic anemia best journals Hemolytic anemia top journals Hemolytic anemia free medical journals Hemolytic anemia famous journals Hemolytic anemia Google Scholar indexed journals Enzyme deficiency articles Enzyme deficiency Research articles Enzyme deficiency review articles Enzyme deficiency PubMed articles Enzyme deficiency PubMed Central articles Enzyme deficiency 2023 articles Enzyme deficiency 2024 articles Enzyme deficiency Scopus articles Enzyme deficiency impact factor journals Enzyme deficiency Scopus journals Enzyme deficiency PubMed journals Enzyme deficiency medical journals Enzyme deficiency free journals Enzyme deficiency best journals Enzyme deficiency top journals Enzyme deficiency free medical journals Enzyme deficiency famous journals Enzyme deficiency Google Scholar indexed journals health articles health Research articles health review articles health PubMed articles health PubMed Central articles health 2023 articles health 2024 articles health Scopus articles health impact factor journals health Scopus journals health PubMed journals health medical journals health free journals health best journals health top journals health free medical journals health famous journals health Google Scholar indexed journals Amoxicillin articles Amoxicillin Research articles Amoxicillin review articles Amoxicillin PubMed articles Amoxicillin PubMed Central articles Amoxicillin 2023 articles Amoxicillin 2024 articles Amoxicillin Scopus articles Amoxicillin impact factor journals Amoxicillin Scopus journals Amoxicillin PubMed journals Amoxicillin medical journals Amoxicillin free journals Amoxicillin best journals Amoxicillin top journals Amoxicillin free medical journals Amoxicillin famous journals Amoxicillin Google Scholar indexed journals G6PD articles G6PD Research articles G6PD review articles G6PD PubMed articles G6PD PubMed Central articles G6PD 2023 articles G6PD 2024 articles G6PD Scopus articles G6PD impact factor journals G6PD Scopus journals G6PD PubMed journals G6PD medical journals G6PD free journals G6PD best journals G6PD top journals G6PD free medical journals G6PD famous journals G6PD Google Scholar indexed journals Cytomegalovirus articles Cytomegalovirus Research articles Cytomegalovirus review articles Cytomegalovirus PubMed articles Cytomegalovirus PubMed Central articles Cytomegalovirus 2023 articles Cytomegalovirus 2024 articles Cytomegalovirus Scopus articles Cytomegalovirus impact factor journals Cytomegalovirus Scopus journals Cytomegalovirus PubMed journals Cytomegalovirus medical journals Cytomegalovirus free journals Cytomegalovirus best journals Cytomegalovirus top journals Cytomegalovirus free medical journals Cytomegalovirus famous journals Cytomegalovirus Google Scholar indexed journals patient articles patient Research articles patient review articles patient PubMed articles patient PubMed Central articles patient 2023 articles patient 2024 articles patient Scopus articles patient impact factor journals patient Scopus journals patient PubMed journals patient medical journals patient free journals patient best journals patient top journals patient free medical journals patient famous journals patient Google Scholar indexed journals medicine articles medicine Research articles medicine review articles medicine PubMed articles medicine PubMed Central articles medicine 2023 articles medicine 2024 articles medicine Scopus articles medicine impact factor journals medicine Scopus journals medicine PubMed journals medicine medical journals medicine free journals medicine best journals medicine top journals medicine free medical journals medicine famous journals medicine Google Scholar indexed journals radiotherapy articles radiotherapy Research articles radiotherapy review articles radiotherapy PubMed articles radiotherapy PubMed Central articles radiotherapy 2023 articles radiotherapy 2024 articles radiotherapy Scopus articles radiotherapy impact factor journals radiotherapy Scopus journals radiotherapy PubMed journals radiotherapy medical journals radiotherapy free journals radiotherapy best journals radiotherapy top journals radiotherapy free medical journals radiotherapy famous journals radiotherapy Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

1. Background

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency is the most common enzyme deficiency, with an estimated 400 million people affected worldwide [1]. There are several variants of the disease resulting in a wide spectrum of presentations ranging from asymptomatic to severe hemolysis. In the most prevalent types, the Mediterranean and the A- variant, hemolysis occurs after an exposure to oxidizing agents, typically antimalarial or sulfonamide drugs; infectious agents, such as Parvovirus, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), or Hepatitis. In this report, we present an intriguing case of severe hemolytic anemia in a 23 year old patient who was exposed to amoxicillin, ten days prior to presentation, and ultimately found to be G6PD deficient. Only two previous associations of severe hemolysis due to amoxicillin exposure have been reported [2, 3] . While rare, no infectious or alternative chemical exposure was found, and no alternative inciting event could be identified. We, therefore, propose that our patient’s presentation of G6PD-mediated hemolytic anemia is likely a result of amoxicillin exposure.

2. Case Presentation

A 23 year old, bi-racial (Hispanic-Caucasian) male was admitted to an outside hospital (OSH) with complaints of jaundice, generalized weakness, and vomiting. On admission, he was noted to have a hemoglobin (Hgb) level of 3.7 mg/dl (Reference Range (RR) 14-18 mg/dl), pancytopenia, and hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin 18.9; RR 0.3-1.2 mg/dl). The patient was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and received 13 units of blood during his admission. An extensive workup, including the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Parvovirus B19, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis panel, and bone marrow biopsy was unrevealing; however, he slowly improved and was discharged home 2 weeks after admission with a Hgb of 8.0 mg/dl. Two days later, he developed non-radiating chest pain, prompting presented to our hospital, at which time he was found to have a Hgb of 8.4 mg/dl. Importantly, 10 days prior to admission to the OSH ICU, the patient had completed a 14-day course of amoxicillin for an infection and subsequent removal of an ingrown toenail. On presentation, the patient denied fevers, chills, rigors, dyspnea, weight-loss, and lymphadenopathy. Review of symptoms was positive for dysuria since placement and subsequent removal of a Foley catheter at the OSH, as well as a mild headache. He reported that he was in his usual state of good health until approximately 1 week after completing the course of amoxicillin, when he began feeling unwell. Two to three days prior to initial admission, he experienced non-bilious, non-bloody emesis and nausea with loose stools. On the morning of admission, his urine became dark and he appeared jaundiced, which prompted his parents to bring him to the OSH’s emergency room. His past medical history was notable for paranoid schizophrenia, for which he was being treated with clonazepam 0.5 mg po BID, quetiapine 25 mg po TID PRN, sertraline 200 mg QD, and ziprasidone 80 mg BID, all of which were discontinued on admission to the OSH. Past surgical history was unremarkable. The patient had no known allergies and denied illicit drug use, tobacco, and alcohol use. Further, the patient was sexually inactive. He had a family history remarkable for unexplained blood clots on his agnate grandmother’s side. A couple of years prior to presentation he had been stationed in Afghanistan without notable illness. On arrival to our medical unit, physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 125/75 Mm Hg, a heart rate of 100 beats per minute (bpm), a respiration rate of 18 breaths per minute, and a temperature of 98.1°F. The patient was alert and oriented, but anxious in appearance. The head-eyes-ears-nose-throat (HEENT) exam revealed scleral icterus, and the cardiopulmonary exam was within normal limits, except for borderline tachycardia. Abdominal exam was notable for diffuse tenderness to deep palpation and splenomegaly without hepatomegaly. No focal deficits were observed on neurological exam, cranial nerves were intact, and no meningismus was appreciated.

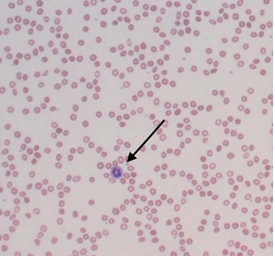

Laboratory findings demonstrated pancytopenia with a low white blood cell (WBC) count of 2.3 thousand/cmm (RR 4.5-11.0 thousand/cmm) and neutrophilic predominance of 68% (RR 37-77%), thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of 105 thousand/cmm (RR 150-350 thousand/cmm), and a hemoglobin and hematocrit that were 8.2 mg/dl and 24%, respectively (Table 1). Absolute reticulocyte count was low at 0.0134 million/cmm (Table 1), with a relative value that was at the low end of normal at 0.4% (RR 0.4-1.9%). A peripheral blood smear was microcytic with central pallor, as shown in Figure 1. Lymphocyte markers assessed by flow cytometry showed no evidence of clonal lymphoid expansion. Erythropoietin was high, osmotic fragility testing and direct red blood cell antibody assay were negative (Table 2). A complete biochemistry panel, including cardiac markers (Troponin, creatine kinase-muscle/brain (CK-MB), creatine kinase (CK)), was unremarkable. Urinalysis (UA) was revealing for 1+ protein, elevated urobilinogen (4.0 mg/dl; RR 0.1-1.0 mg/dl), 2+ leukocyte esterase and positive nitrites; urine microscopy showed 29 RBC/high-powered field (hpf) and 185 WBC/hpf. Urine drug screen was negative. Liver function tests revealed an elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/ serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT)/ serum glutamate-pyruvate transaminase (SGPT), with alkaline phosphatase within normal limits (Table 3). International normalized ratio (INR) was 1.21 and total bilirubin was 4.05 mg/dl (RR 0.3-1.2 mg/dl) with a direct bilirubin of 1.1 mg/dl (RR 0.00-0.34 mg/dl), as shown in Tables 2 and 3. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) resulted 1080 U/L (RR 135-225 U/L); D dimer was 300; total protein was within normal limits, and C-reactive protein (CRP) was unremarkable (Table 2). Both ferritin and fibrinogen were elevated at 911 ng/ml (RR 10-385 ng/ml) and 426 mg/dl (RR 198-450 mg/dl),

respectively (Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 1: Microcytic, normochromic peripheral smear with moderate anisopoikilocytosis. Neutrophils (arrow) are mildly decreased in number, with unremarkable morphology.

|

Compound |

Sample |

Result |

Reference Range |

Units |

|

Hemoglobin (Hgb) |

Blood |

8.2 (L) |

14-18 |

mg/dl |

|

Hematocrit (Hct) |

Blood |

24 (L) |

40-54 |

% |

|

Mean Corpuscular Value (MCV) |

Blood |

78.9 (L) |

80-96 |

fL |

|

White Blood Cell (WBC) |

Blood |

2.3 (L) |

4.5-11.0 |

thousand/cmm |

|

Red Blood Cells |

Blood |

3.04 (L) |

4.6-6.2 |

million/cmm |

|

Platelets |

Blood |

105 (L) |

150-350 |

thousand/cmm |

|

Reticulocyte Absolute Count |

Blood |

0.0134 (L) |

0.026-0.095 |

million/cmm |

|

Reticulocyte Relative Value |

Blood |

0.4 |

0.4-1.9 |

% |

Table 1: Complete Blood Count.

|

Compound |

Sample |

Result |

Reference Range |

Units |

|

Hematologic Labs |

||||

|

CD4 |

Blood |

65 (H); 275 (L) |

30-61; 490-1740 |

cells/µl |

|

CD8 |

Blood |

19; 79 (L) |

12-42; 180-1170 |

cells/µl |

|

CD4/CD8 Ratio |

Blood |

3.48 |

0.86-5.00 |

- |

|

Complement, CH50 |

Serum |

54 |

31-60 |

U/ml |

|

Cold Agglutinins |

Serum |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Direct RBC Ab Assay |

Blood |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

COOMBS test |

Blood |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Donate Landsteiner |

Flexitest, Serum |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Erythropoietin |

Serum |

225.9 (H) |

2.6-18.5 |

mIU/ml |

|

D-Dimer |

Plasma |

300 (H) |

< 234 |

ng/ml FEU |

|

Haptoglobin |

Serum |

< 15 (L) |

43-212 |

mg/dl |

|

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) |

Serum |

1080 (H) |

135-225 |

U/L |

|

International Normalized Ratio (INR) |

Plasma |

1.21 |

0.83-1.26 |

- |

|

Ceruloplasmin |

Serum |

30 |

18-36 |

mg/dl |

|

Fibrinogen |

Plasma |

426 |

198-450 |

mg/dl |

|

Hemosiderin |

Urine |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Vitamin B12 |

Serum |

572.8 |

200-900 |

pg/ml |

|

Osmotic fragility test |

Blood |

Normal |

Normal |

% |

|

Rheumatologic Labs |

||||

|

Anti-Neutrophil cytoplasmic Antibody (ANCA) |

Serum |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Rheumatoid Factor (RF) |

Serum |

5 |

<= 14 |

IU/ml |

|

Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide (CCP) Antibody |

Serum |

< 16 |

<= 20 |

U |

|

Sjogren’s Antibody (SSA) |

Serum |

< 1.0 |

<= 1.0 |

U |

|

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) |

Blood |

60 (H) |

0-15 |

mm/hr |

|

C-Reactive Protein (CRP) |

Serum |

3.38 |

< 0.8 |

mg/dl |

|

Sjogren’s Antibody (SSB) |

Serum |

< 1.0 |

<= 1.0 |

U |

Table 2: Hematologic and Rheumatologic Labs.

|

Compound |

Sample |

Result |

Reference Range |

Units |

|

Liver Function tests |

||||

|

Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) |

Serum |

84 (H) |

15-46 |

U/L |

|

Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) |

Serum |

89 (H) |

11-66 |

U/L |

|

Alkaline Phosphatase |

Serum |

51 |

38-126 |

U/L |

|

Total Bilirubin |

Serum |

4.03 (H) |

0.3-1.2 |

mg/dl |

|

Direct Bilirubin |

Serum |

1.1 (H) |

0.00-0.34 |

mg/dl |

|

Total Protein |

Serum |

6.7 |

6.0-8.3 |

g/dl |

|

Albumin |

Serum |

4.3 |

3.5-5.0 |

g/dl |

|

Iron Studies |

||||

|

Iron |

Serum |

83 |

49-181 |

ug/dl |

|

Folate |

Serum |

9.04 |

2.5-17 |

ng/ml |

|

Iron Saturation |

Serum |

32.0c |

20-50 |

% |

|

Total Iron Binding Capacity (TIBC) |

Serum |

262c |

250-450 |

ug/dl |

|

Ferritin |

Serum |

911 (H) |

10-385 |

ng/ml |

Table 3: Liver Function Tests and Iron Studies.

|

Infection Cause |

Sample |

Result |

Reference Range |

Units |

|

Adenovirus |

Serum |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) |

Serum |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) |

Plasma |

< 200 |

<= 200 |

copies/ml |

|

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) |

Serum |

Not Detected |

Not Detected |

- |

|

Parvovirus B19 |

Serum |

Not Detected |

Not Detected |

- |

|

Parvovirus B19 |

Bone Marrow |

Not Detected |

Not Detected |

- |

|

Enterovirus |

Plasma |

Not Detected |

Not Detected |

- |

|

HIV |

Serum |

Nonreactive |

Nonreactive |

- |

|

Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR) |

Serum |

Nonreactive |

Nonreactive |

- |

|

Hepatitis A |

Serum |

Nonreactive |

Nonreactive |

- |

|

Hepatitis B |

Serum |

< 20 |

<= 20 |

IU/ml |

|

Hepatitis C |

Serum |

Nonreactive |

Nonreactive |

- |

|

Toxoplasma gondii |

Serum |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Histoplasma capsulatum |

Urine |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Cryptococcus neoformans |

Serum |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Ehrlichia chaffeensis |

Serum |

Not Detected |

Not Detected |

- |

|

Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

Blood |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Borrelia burgdorferi |

Serum |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Rickettsia rickettsii |

Serum |

Not Detected |

Not Detected |

copies/ml |

|

Coccidioides immitis |

Plasma |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Bartonella henselae |

Serum |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Leptospira interrogans |

Serum |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Haemophilus influenzae |

Serum |

Negative |

Negative |

µg/mL |

|

Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

Urine |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Chlamydia trachomatis |

Urine |

Negative |

Negative |

- |

|

Eosinophilia |

Urine |

0 |

0-1 |

% |

|

Urine culture |

Urine |

Positive-Klebsiella pneumoniae |

no growth |

cfu/ml |

Table 4: Infectious Disease Labs.

A chest radiograph proved to be normal and abdominal CT showed marked splenomegaly (not shown). CD 4 counts and percentages were normal. Cold agglutinins were negative, as was a COOMBS test. Donnath Landsteiner test was also negative (Table 2). The infectious workup was grossly negative (Table 4). The only source of infection found was the patient’s UA, as above, revealing for a urinary tract infection (UTI) that grew Klebsiella pneumoniae, which was attributed to an indwelling Foley catheter during his 7-day stay at the OSH ICU. Rheumatology tests were also negative, including Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies (ANCA) and Rheumatoid factor (Table 2). Subsequently, a bone marrow biopsy was performed, showing a hypercellular marrow (90%) with remarkable erythroid hyperplasia and left shift, mild megakaryocytic hyperplasia without dysplasia or atypia, with no atypical cell infiltrate identified. A repeat reticulocyte count, 11 days after admission, resulted as an absolute value of 0.0261 mill/cmm (RR 0.026-0.095 mill/cmm) and a relative value of 0.9% (RR 0.4-1.9%). G6PD testing by enzymatic methods used for definitive diagnosis [4] yielded positive results for deficiency. The patient’s transfusion requirements diminished, as he only required an additional 2 units of packed red blood cells and was treated for his UTI with ciprofloxacin.

The patient was discharged on a steroid taper and folic acid. Two months after discharge, hemoglobin normalized to 15.5 g/dl. He continued to improve steadily at home and three months after initial symptoms, he fully recovered and returned to his prior state of health and activity level. He has not had any further hemolytic events, however received follow-up in our Hematology/Oncology clinic.

3. Discussion

G6PD is the most common enzyme deficiency worldwide, with a global prevalence of 4.9% [1]. For the majority of people affected, G6PD deficiency is asymptomatic; however, upon exposure to oxidizing or infectious agents, hemolysis can occur, leading to precipitous drops in blood counts requiring hospital admission and blood transfusion. The patient described in this case report presented with severe hemolysis, requiring multiple administrations of blood products, in addition to an extended hospital admission due to ongoing hemolysis. After extensive laboratory testing investigation, G6PD deficiency was revealed. Interestingly, the only new exposure prior to the onset of hemolysis was to amoxicillin, which albeit rare, has previously been reported to induce hemolysis in two prior published cases [2, 3], with one being in a G6PI deficient patient [2]. Although our patient was 10 days post-exposure at initial admission, he reported a 1-week history of symptoms, which fits with the reported timeline in these previously-published cases.

The reticulocyte count was an unexpected finding in this patient. In conditions of massive hemolysis, an elevated reticulocyte count would be expected in a normally functioning bone marrow. In this patient, however, lab tests revealed a low reticulocyte count at admission. Bone marrow biopsy revealed a hyper-cellular bone marrow, suggesting either a response to hemolysis, or bone marrow involvement, which was ruled out with flow cytometry

methods. A repeat reticulocyte count 11 days after presentation indicated a mild improvement, but the response remained suboptimal. Aplastic crisis has been previously reported in G6PD deficient patients, however, these were found to be a result of inciting viral infections such as CMV [5] and Parvovirus [6], which were not detected in our patient. Furthermore, splenomegaly has been associated with ongoing hemolysis in G6PD deficient patients and may explain the lack of reticulocytosis due to splenic sequestration and subsequent destruction.

The extended duration of chronic ongoing hemolysis was similar to that seen in the autoimmune hemolytic anemias. However, arguing against this etiology was a negative Coombs test, as well as a high bilirubinemia, which is not typically seen in immune-mediated reactions. After exhausting our investigation for potential triggers of hemolysis in G6PD deficient patients, no other alternate source accounts for our findings. In addition to inducing hemolysis in G6PD deficient patients, amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid combinations have both been reported to cause neutropenia and pancytopenia in non-G6PD deficient patients being treated for a variety of infections [7-9]. Further, there are 97 reports of bone marrow failure associated with amoxicillin that were reported to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [10]. Additionally, there are many reports of the combination amoxicillin/clavulanic acid antibiotic therapy causing hepatotoxicity [11] and some reports of amoxicillin alone causing hepatitis [12,13], as was observed in our patient.

Oxidative stress is a known mechanism of drug-induced hemolytic episodes in G6PD deficient patients [14-16]. G6PD protects cells from oxidative stress by playing a role in the reduction of glutathione, an important antioxidant and an essential component required for the maintenance of the normal RBC structure [17]. Bactericidal antibiotics, including β-lactams such as amoxicillin, have been shown to cause mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in oxidative damage [18]. Due to the late presentation of the patient to our hospital, direct confirmation of amoxicillin-induced hemolysis was not possible; however, our findings strongly suggest that this patient’s severe hemolytic anemia was possibly associated with amoxicillin exposure. Oxidative stress (potentially as a result of amoxicillin exposure), which is a known initiator of hemolysis in G6PD deficient patients, may have been severe enough to produce significant, ongoing hemolysis, as well as hepatotoxicity and subsequent splenomegaly in this case presentation. It would be of particular interest to perform genotyping testing of G6PD deficient patients to define particular G6PD variants that could determine which patients would be especially susceptible to amoxicillin-triggered hemolysis. New insights into G6PD polymorphisms may provide some clarification and better allude to the potential susceptibility of those patients that would respond with a severe hemolysis after amoxicillin exposure.

In conclusion, we describe an unusual presentation of severe hemolytic anemia, likely related to amoxicillin exposure in a G6PD deficient patient. These findings, in conjunction with previously-published cases, highlight the need to consider amoxicillin as a cause for the presenting symptoms described in this case report. Increased awareness of such potential would warrant caution when prescribing amoxicillin to G6PD deficient patients and may argue for further characterization of the precise G6PD variant, once a deficiency has been established.

Disclosures and Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any disclosures.

Funding

This material is the result of work supported in part with resources and the use of facilities at the Atlanta VA Medical Center.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Bartholomew for his editing suggestions.

References

- Nkhoma ET, Poole C, Vannappagari V, et al. The global prevalence of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Cells Mol Dis 42 (2009): 267-278.

- Rossi F, Ruggiero S, Gallo M, et al. Amoxicillin-induced hemolytic anemia in a child with glucose 6-phosphate isomerase deficiency. Ann Pharmacothe 44 (2010):1327-1329.

- Gmür J, Wälti M, Neftel KA. Amoxicillin-induced immune hemolysis. Acta Haematol 74 (1985): 230-233.

- Minucci A, Giardina B, Zuppi C, et al. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase laboratory assay: How, when, and why? IUBMB Life 61 (2009): 27-34.

- Garcia S, Linares M, Colomina P, et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection And Aplastic Crisis In Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency. The Lancet 330 (1987): 105.

- Goldman F, Rotbart H, Gutierrez K, et al. Parvovirus-associated aplastic crisis in a patient with red blood cell glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Pediatr Infect Dis J 9 (1990): 593-594.

- Irvine AE, Agnew AND, Morris TCM. Amoxycillin Induced Pancytopenia. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition) 290 (1985): 968-969.

- Rouveix B, Lassoued K, Vittecoq D, et al. Neutropenia due to beta lactamine antibodies. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 287 (1983): 1832-1834.

- Mansour H, Saad A, Azar M, Khoueiry P. Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid-induced thrombocytopenia. Hosp Pharm 49 (2014): 956-960.

- Is Bone Marrow Failure a side effect of amoxicillin?? (FactMed.com) (2018).

- Stine JG, Chalasani N. Chronic liver injury induced by drugs: a systematic review. Liver Int 35 (2015): 2343-2353.

- Oxlund J, Ferguson AH. Amoxicillin-induced hepatitis. Ugeskr Laeg 173 (2011): 1885-1886.

- Fontana RJ, Shakil AO, Greenson JK, et al. Acute liver failure due to amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanate. Dig Dis Sci 50 (2005): 1785-1790.

- Fang Z, Jiang C, Tang J, et al. A comprehensive analysis of membrane and morphology of erythrocytes from patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. J Struct Biol 194 (2016): 235-243.

- Tang HY, Ho HY, Wu PR, et al. Inability to maintain GSH pool in G6PD-deficient red cells causes futile AMPK activation and irreversible metabolic disturbance. Antioxid Redox Signal 22 (2015): 744-759.

- Ganesan S, Chaurasiya ND, Sahu R, et al. Understanding the mechanisms for metabolism-linked hemolytic toxicity of primaquine against glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficient human erythrocytes: evaluation of eryptotic pathway. Toxicology 294 (2012):54-60.

- Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L. Glucose 6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Plays a Key Role in Protection Against Reactive Oxygen Species. Biochemistry 5th edition (2002).

- Kalghatgi S, Spina CS, Costello JC, et al. Bactericidal antibiotics induce mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in Mammalian cells. Sci Transl Med 5 (2013): 192ra85.