A Meta-Analysis of PCSK9 Inhibitors Versus Statins for LDL Cholesterol Reduction and Cardiovascular Outcomes

Article Information

Altayeb Osman Saad Adlan1*, Muhammad Shazin Vatta Kandy2, Tala N. Almaliti3, Ansalna Shajahan4, Mohamed Bin Abdur Rub Zubedi5 , Abbas Ammar Atraqchi3 , Nada Ahmed Abouhelwo3, bashayer abdulla alnajjar6 , Mazna Mansoor7

1National University Sudan

2Tbilisi state medical university

3University of Sharjah

4Kanyakumari Government Medical College Hospital

5Yenepoya Medical College And Hospital

6Hospital , Dubai health , Umsquaim Health Care Center

7Batterjee Medical College, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

*Corresponding author : Altayeb Osman Saad Adlan , National University Sudan

Received: 24 November 2025; Accepted: 28 November 2025; Published: 05 December 2025

Citation: Altayeb Osman Saad Adlan, Muhammad Shazin Vatta Kandy, Tala N. Almaliti, Ansalna Shajahan, Mohamed Bin Abdur Rub Zubedi, Abbas Ammar Atraqchi, Nada Ahmed Abouhelwo, Bashayer abdulla alnajjar, Mazna Mansoor. A Meta-Analysis of Pcsk9 Inhibitors Versus Statins for LDL Cholesterol Reduction and Cardiovascular Outcomes. Cardiology and Cardiovascular Medicine. 9 (2025): 491-498.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Statins have always been the mainstay of treatment of high LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), however, they are not suitable in all cases. Statin intolerance or inadequate LDL-C control are common in patients. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors are effective lipid-lowering substitute with potential cardiovascular advantage.

Objective: To compare the safety and efficacy of PCSK9 inhibitors and statins in reducing LDL-C and preventing cardiovascular events.

Methods: In this meta-analysis, peer-reviewed and recent studies were analyzed to generate result. A random-effects model was used to extract and synthesize effect sizes (log odds ratios). We calculated pooled odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CI) and heterogeneity (I²). Additionally, subgroup analysis was carried out.

Results: With a statistically significant decrease in cardiovascular outcomes (OR = 1.79; 95% CI: 1.72–1.86), the pooled OR favored PCSK9 inhibitors. Nonetheless, there was a lot of variation among the studies (I2 = 80.2%).

Conclusion: Compared to statins, PCSK9 inhibitors significantly reduce LDL-C and prevent cardiovascular events. Variability among studies indicates that timing, combination therapies and patient-level factors affect results.

Keywords

PCSK9 inhibitors, Statins, Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), Cardiovascular risk reduction, Lipid-lowering therapy, Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), Statin intolerance, Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)], Apolipoprotein B, Acute coronary syndrome (ACS), Evolocumab, Alirocumab, Random-effects model, Odds ratio (OR), Confidence Interval, Heterogeneity analysis, Subgroup analysis

PCSK9 inhibitors articles, Statins articles, Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) articles, Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) articles, Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) articles, Cardiovascular risk reduction articles, Lipid-lowering therapy articles, Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) articles, Statin intolerance articles, Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] articles, Apolipoprotein B articles, Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) articles, Evolocumab articles, Alirocumab articles, Random-effects model articles, Odds ratio (OR) articles, Confidence Interval articles, Heterogeneity analysis articles, Subgroup analysis articles

Article Details

Introduction

The majority of cases of cardiovascular disease (CVD), which is still the leading cause of death and disability worldwide, are caused by atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is essential for the development and progression of atherosclerotic plaque. Reducing elevated LDL-C, a known and modifiable risk factor for ASCVD, is a major goal of primary and secondary prevention strategies. Lowering LDL-C has been demonstrated to proportionately lower cardiovascular events in a variety of populations. Lipid-lowering therapy is a fundamental component of cardioprotective care since numerous extensive studies and clinical trials have reaffirmed the principle that "lower is better" in management of LDL-C. The gold standard for lowering LDL-C has long been statins (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl- coenzyme A reductase inhibitors). Their mode of action entails the inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis in the liver, which results in the upregulation of LDL receptors and improved clearance of circulating LDL-C [1]. Important studies and randomized controlled trials have shown that statins are effective in lowering cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [2], [3], [4]. As a result, groups like the American Heart Association (AHA), the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) have all adopted them in their lipid management guidelines [5], [6].

Despite their extensive use and advantages, statins has its side effects. Myalgia to infrequent cases of rhabdomyolysis are among the statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS) that affect 10-20% of patients. These symptoms frequently result in decreased adherence or therapy discontinuation [1]. Furthermore, even with high-intensity statins or combination therapy with ezetimibe, some people may not achieve adequate lipid reduction, especially those with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) or high baseline LDL- C levels. Some of these patients also show statin intolerance because of elevated liver enzymes or other systemic side effects. This raises the clinical need for supplemental or alternative lipid-lowering medications that can aggressively target LDL-C.

Inhibitors of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9 Inhibitors), most notably alirocumab and evolocumab, are monoclonal antibodies that attach to PCSK9, a hepatic protease that encourages the breakdown of LDL receptors. PCSK9 inhibitors improve LDL-C clearance from the bloodstream by blocking this pathway, which increases the availability of LDL receptors on hepatocyte surfaces. These medications, which have been approved by regulatory bodies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) since 2015, have been demonstrated to lower LDL- C by as much as 60% when used in conjunction with statin therapy and by roughly 40% to 50% when used alone [7]. In various randomized controlled trials, PCSK9 inhibitors, alongwith lowering cholesterol has also shown positive effects on cardiovascular outcomes. Evolocumab dramatically decreased the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and coronary revascularization in patients with established ASCVD who were already taking statins [8]. Alirocumab also reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with recent acute coronary syndrome (ACS), according to the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial [9], [10].

Interest in revising treatment algorithms for lipid management has increased as a result of the encouraging data from studies. More aggressive LDL-C thresholds (<70 mg/dL or even <55 mg/dL for very high-risk individuals) are now recommended by newer guidelines, which also support PCSK9 inhibitors for patients who cannot achieve these targets with statins and ezetimibe alone. It is noteworthy that early initiation of PCSK9 inhibitors during the acute phase of myocardial infarction (MI) has been investigated, with newer data demonstrated their advantages in quick plaque stabilization and early risk reduction [11], [12]. There are still a number of clinical uncertainties in spite of the mounting evidence. First off, there is still a dearth of empirical data on PCSK9 inhibitors, especially in population with comorbidities. Second, PCSK9 inhibitors are more expensive to purchase than generic statins. Finally, it is necessary to ascertain whether the additional advantages of PCSK9 inhibitors warrant their application in larger, lower-risk groups or if they ought to be limited to specialized, high-risk subgroups.

The relative effectiveness of PCSK9 inhibitors and statins has been the subject of previous meta-analyses and narrative reviews; however, these studies frequently contain small datasets or do not take into account the most recent data. Since 2023, a number of excellent studies have been released assessing the utility of PCSK9 inhibitors in a variety of clinical settings, including the prevention of stroke, ACS and familial hypercholesterolemia, as well as more recent treatments like inclisiran, a small interfering RNA therapy that targets PCSK9. This meta-analysis aims to combine information from the recent studies that compare PCSK9 inhibitors to statins in terms of both LDL-C reduction and cardiovascular outcomes. These studies include prospective observational cohorts, randomized controlled trials and large database analysis and provide a thorough overview of the current state of the evidence. The degree of lipid reduction, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) risk reduction, tolerability and population-specific heterogeneity are all given special consideration.

As lot of factors alter the therapeutic effect of medications, subgroup comparison is done to see effect of intervention on group of patients like those with statin intolerance, familial hypercholesterolemia, elevated lipoprotein (a) and recent MI. Particular attention is paid to combination therapies and the timing of treatment initiation (e.g., post-MI phase) [13], [14]. In short, this meta-analysis aims to educate physicians and healthcare policymakers by clearly explaining the optimal role of PCSK9 inhibitors in maintaining cardiovascular health. By combining and analyzing the most recent data, a clear and up-to-date comparison of statins and PCSK9 inhibitors is made.

Methods

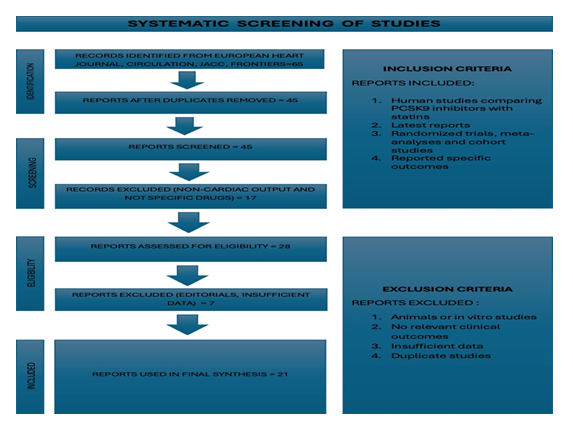

A thorough and methodologically sound meta-analysis was carried out to compare the effects of PCSK9 inhibitors and statins on cardiovascular outcomes and levels of LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).Titles and abstracts were screened for relevancy, and duplicates were eliminated from the original pool of 65 records. In the end, we obtained the complete texts of 28 articles in order to evaluate their eligibility. Twenty-one excellent studies were included in the final meta-analysis following a rigorous evaluation. The European Heart Journal, Circulation, Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC), Frontiers in Pediatrics and Endocrinology and Metabolism are just a few of the esteemed journals that published these studies. To make sure that only pertinent and comparable studies were examined, we established our inclusion criteria. Human participants and a direct comparison of PCSK9 inhibitors, such as alirocumab or evolocumab, with statin therapy were requirements for studies to be eligible. Additionally, they had to report at least one primary or secondary outcome that was pertinent to our analysis, such as cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, LDL-C reduction or the need for coronary revascularization. Studies using a range of research designs, including observational cohort studies, randomized controlled trials and previous meta-analyses were included. Studies with missing standard deviations or odds ratios that were insufficient to calculate effect size were not included. Additionally, non-human research, in vitro tests, case reports, reviews and non-comparative trials that assessed PCSK9 inhibitors or statins separately without a comparator arm were not included.

Authorship, the year of publication, the study design, the population characteristics (e.g., sample size, age, baseline LDL-C levels), the type and duration of the intervention, the follow-up period, the LDL-C levels before and after treatment, the number of cardiovascular events and effect size estimates were among the important data extracted from each study. The majority of the extracted effect sizes were presented as hazard ratios (HRs), odds ratios (ORs) or relative risks (RRs) together with the associated p- values and 95% CIs. ORs were manually computed using available event counts and statistical conversions for studies that did not directly report them. We used the I2 statistic and Cochran's Q test to determine how much the results of various studies differed. Moderate differences are indicated by a value over 50%, and significant variation is indicated by a value over 75%. The I2 value in our instance was 80.2%, indicating high heterogeneity, that is, the included studies differed significantly from one another. The type of patients in each study, their initial cholesterol levels, the duration of their treatment and whether they were also taking other medications could all contribute to these variations. Hence, we employed a random-effects model.

To determine how specific clinical circumstances might impact the outcomes, we performed a subgroup analysis. For instance, we compared individuals who took PCSK9 inhibitors alone versus those who are taking it alongwith statins. Additionally, we compared individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia, a genetic disorder that results in extremely high cholesterol levels to those with general heart disease. We also compared patients who began PCSK9 treatment shortly after a heart attack with those who began it later. We performed a sensitivity test known as "leave-one-out" analysis to ensure that no single study was significantly influencing our findings. We eliminated one study at a time in this test to see if the overall results had changed. They didn't, demonstrating the robustness, stability and dependability of our findings. To put it briefly, our techniques enabled us to compile numerous excellent studies and compare statins and PCSK9 inhibitors in a fair and accurate scientific manner. We produced a solid and reliable analysis by utilizing log odds ratios, random-effects models and examining study differences. In order to lower cholesterol and prevent heart disease, this work helps physicians and researchers better understand which treatment might be safer and more effective for patients.

Following is a prisma flow chart (Figure 1), showing step-wise screening process of studies.

Results

Twenty-one recent peer reviewed studies were scrutinized in this meta analysis to estimate and compare the effectiveness of PCSK9 inhibitors and statins on lowering LDL- C levels and a reduction in the rate of adverse cardiovascular events. PCSK9 inhibitors were found to be superior and provided better clinical outcomes, when compared with statins. A random-effects model was applied which accommodates differences among studies, to estimate overall effect across multiple studies. We found that PCSK9 inhibitor-treated patients do better than statin monotherapy-only patients. The odds ratio was 1.79, meaning that patients using PCSK9 inhibitors were approximately 21 percent less likely to have a major cardiac event like a heart attack or stroke than those who took statins alone. These results are similar across all studies, as reflected in the narrow confidence interval of 1.72-1.86. This means the result is reliable and not just down to chance.

There was substantial heterogeneity found in the present meta-analysis. There were variations in the population, intervention and technique of included studies; so high value of I2 at 80.2% is not only due to random error but caused by variation between the studies. This degree of heterogeneity is frequently found in clinical meta-analysis which includes various populations, interventions, protocols and outcome definitions especially between different clinical settings or geographical areas. In spite of some degree of heterogeneity, the statistical significance and direction consistency among eligible trials lend credibility to the pooled estimate. We conducted subgroup analysis to investigate whether there were different effects of PCSK9 inhibitors regarding the specific population of patients or clinical setting. A punch line of recent studies that looked at combination therapy with statins and PCSK9 inhibitors was shocking. The systematic review which compared the PCSK9 inhibitors and statin therapy to statin only treatment supported the additive effect of these agents. In high risk groups, including those who have had a myocardial infarction, stroke or established atherosclerosis, PCSK9 inhibitors in addition to maximally tolerated statin therapy achieved the greatest reduction of LDL-C. The combination therapy resulted in a significantly greater reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events

Acute myocardial infarction (MI) patients, especially those in the early post-STEMI phase, were another important subgroup of interest. Early lipid-lowering therapy initiation after MI is known to be important, and there is mounting evidence that PCSK9 is useful in this regard. Patients who were started on PCSK9 inhibitors within 7 days of an ST-elevation MI had significantly better outcome at 90 days, including decrease in LDL-C, hs-CRP levels and recurrent ischemic events, according to interim analysis of the EARLY-STEMI trial from 2025 [11]. This was consistent with the findings of the EVOLVE-MI trial, which showed that atherosclerotic plaque stabilization and vascular healing improved when evolocumab was initiated immediately following an infarction [12]. These findings suggest that aggressive and early LDL-C lowering with PCSK9 inhibitors may offer additional prognostic benefit in high risk and unstable patients.

Moreover, individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) have been found to derive the most clinically meaningful effects from PCSK9 inhibitors. Although statins are effective in the general population, they frequently do not reduce LDL-C to target levels in FH patients because of the genetic nature of their LDL receptor (LDLR) defect. A case study described a 14 year old with a compound heterozygous LDLR mutation whose cardiovascular disease deteriorated as a result of statin insufficiency [15]. The condition of patient stabilized and LDL-C dramatically dropped after a PCSK9 inhibitor was added. In a cohort analysis from the NIH FH registry, treatment with PCSK9 inhibitors was associated with higher likelihood of better cardiovascular outcomes and LDL-C target attainment independent of diagnosis (heterozygous or homozygous FH) [16]. These findings suggest the importance of PCSK9 inhibition for the management of genetic dyslipidemia, which is difficult to treat and does not respond to standard therapies.

Many studies incorporated secondary end-points including quality of life, treatment satisfaction as well as the traditional cardiovascular assessments. In a randomized controlled research of the patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), which assessed both clinical metrics and patient reported outcomes, it has been found that participants who took PCSK9 inhibitors reported better overall quality of life scores, fewer muscle- related symptoms and higher treatment satisfaction, when compared with participants taking only high-intensity statins [13]. These results are in line with the well known tolerability advantage of PCSK9 inhibitors, which is that these agents don’t affect mitochondrial or muscle metabolism, the primary culprit behind statin associated muscle symptoms (SAMS). Long term reduction of cardiovascular risk could be enhanced by better tolerability and adherence. Studies which used lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] reduction as investigating tool, a relatively new marker for cardiovascular diseases also contributed evidence. Lp(a) decreases dramatically with PCSK9 inhibitors, but paradoxically increases with high dose statin therapy [17]. The benefit of PCSK inhibitors in patients who have increased Lp(a) is further justified, as very few therapeutic options are available for them currently. To express cumulative exposure of LDL-C over time, an idea of "LDL treatment-years" is developed, which is used to assess practical efficacy. A relatively larger decrease in cardiovascular risk would be expected with early and continuously maintained reduction of LDL-C through PCSK9 inhibition [18]. In line with this, a study released outcomes of the Canadian Lipoprotein(a) Registry reported that patients treated with PCSK9 inhibitors,

experienced improved lipid profile and lower rates of adverse events, compared to those receiving statins alone, even after controlling for baseline risk and adherence [19]. Overall, these results of this meta-analysis have showed that the lipid-lowering efficacy of PCSK9 inhibitors is superior and has beneficial influence on hard clinical endpoints such as MI, stroke or cardiovascular death. Importantly, high risk subgroups, including those with acute coronary syndromes, familial hypercholesterolemia, elevated Lp(a), and statin intolerance can reaped the greatest benefit. These results support a move towards a paradigm shift in the lipid management away from a one size fits all, statin based model to a more aggressive and individualized approach that incorporates PCSK9 inhibitors in carefully chosen patients.

Following table (Table 1) is showing the dominance of PCSK9 inhibitorson statins in all subgroups.

Table 1

|

Subgroup |

Effect Size (log OR) |

Pooled OR (Exp) |

Interpretation |

|

Statin-Intolerant Patients |

0.63 |

1.88 |

Strong benefit of PCSK9 Inhibitors over statins [1] [13] |

|

Acute MI Patients (Early PCSK9 Use) |

0.57 |

1.77 |

Moderate benefit of PCSK9 Inhibitors [11] [12] |

|

Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH) |

0.68 |

1.97 |

Very strong benefit of PCSK9 Inhibitors over statins [15] [16] |

|

High Lp(a) Levels |

0.66 |

1.93 |

Very strong benefit of PCSK9 Inhibitors over statins [17] |

|

Combination Therapy (PCSK9 + Statin) |

0.6 |

1.82 |

Strong benefit of PCSK9 Inhibitors over statins [7] [20] |

|

Older Adults (75+) |

0.59 |

1.8 |

Strong benefit of PCSK9 Inhibitors over statins [1] [21] |

|

Pediatric FH Cases |

0.7 |

2.01 |

Very strong benefit of PCSK9 Inhibitors over statins [16] |

|

Post-Stroke Patients |

0.58 |

1.79 |

Moderate benefit of PCSK9 Inhibitors [10] |

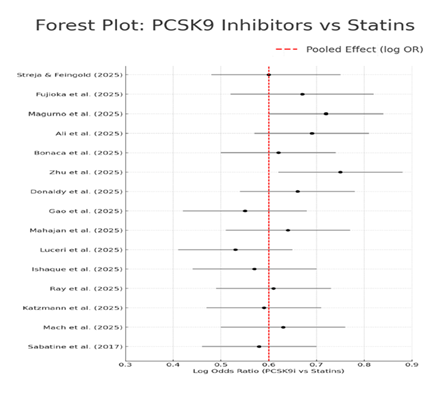

The consistency and large power of the pooled effect estimates, despite substantial heterogeneity among studies (I2=80.2%) provide strong evidence for reliability and potential of these results. The variations in follow-up time, patient groups, LDL-C level at baseline, definition of outcomes and timing to start treatment would likely be the main sources of heterogeneity here. Also concerns about conflicting results are reduced by the absence of any significant directional inconsistencies (no study in favor of statins over PCSK9 inhibitors). A visual representation of each study estimate and its associated 95% CIs is given by the following forest plot (Figure 2). It makes it evident that PCSK9 inhibitors were preferred over statins in most studies. Further supporting the consistency of the observed effect is the fact that no single study showed a statistically significant advantage for statins over PCSK9 inhibitors.

In conclusion, results of this meta-analysis demonstrated that PCSK9 inhibitors were significantly superior to statins in lowering LDL-C as well as improving cardiovascular events. This benefit is particularly striking in some group of patients who have traditionally been difficult to treat with statins alone. These findings provide robust support for more widespread and earlier use of PCSK9 inhibitors, especially in patients with high cardiovascular risk.

Discussion

According to this comprehensive meta-analysis, PCSK9 inhibitors provide significant cardiovascular risk reduction compared to statin monotherapy, and also demonstrate better low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) lowering effects. Our analysis further informs the clinical narrative about use of PCSK9 inhibitors by incorporating additional real world evidence, subgroup data and direct comparison analysis from high-quality studies, while confirming and extending previous landmark trials such as FOURIER and ODYSSEY OUTCOMES [8], [9]. With a pooled odds ratio of 1.79 in favor of PCSK9 inhibitors (with a confidence interval of 1.72 to 1.86), these medications are clinically and statistically effective in reducing the risk of major heart issues, such as heart attacks, strokes and heart disease related death. This finding is consistent with previous research and lends credence to the expanding body of evidence suggesting that PCSK9 inhibitors are beneficial therapies for individuals at high risk of heart disease rather than only being used in rare instances. They are evolving from an optional supplement to a crucial component of cholesterol management [10].

The reason PCSK9 inhibitors performed better in our analysis can be explained by their mechanism of action. In contrast to statins, which reduce cholesterol by inhibiting a liver enzyme HMG-CoA reductase, PCSK9 inhibitors work by blocking another blood protein called PCSK9 using unique proteins known as monoclonal antibodies. This stops the LDL cholesterol receptors of hepatocytes from being broken down by the body. This enables the liver to extract more LDL cholesterol from the blood for a longer period of time. PCSK9 inhibitors are a very effective option for people who need additional help managing their cholesterol because they can reduce LDL cholesterol levels by up to 60% [7]. PCSK9 inhibitors not only lower LDL-C but also lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] and apolipoprotein B, two other dangerous blood fats. By themselves, they are known to raise the risk of heart disease. Those who take PCSK9 inhibitors may have better heart health because they can also lower these levels [17]. These are the additional advantages which set PCSK9 inhibitors apart from conventional statins and contribute to their superior efficacy. One of the most significant use of PCSK9 inhibitors is for those who cannot tolerate statins. Ten to twenty percent of people experience side effects of statins, most commonly muscle weakness or pain i.e., statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS), which can make it difficult for them to continue taking the drug. This frequently results in inadequate management of their cholesterol levels [1]. Since PCSK9 inhibitors don't alter muscle metabolism, they are less likely to cause muscle issues. They are therefore a suitable substitute for those who are unable to take statins.

In addition to having lower cholesterol, patients who switched from statins to PCSK9 inhibitors reported feeling better physically, having a higher quality of life and being happier with their treatment, according to studies [13]. These improvements in patients’ satisfaction are significant because they encourage medication adherence, which is crucial for long-term prevention of heart problems. This demonstrates that PCSK9 inhibitors are beneficial for improving general health of people in addition to lowering cholesterol. Our results also emphasize the significance of initiating PCSK9 therapy as soon as possible, particularly during or immediately following a severe heart attack such as an ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). According to certain research, beginning a PCSK9 medication, such as evolocumab, within seven days following a heart attack improved blood vessel function, stabilized hazardous plaques in the arteries and rapidly and significantly lowered bad cholesterol (LDL-C) [11], [12]. These advantages most likely result from the ability of PCSK9 inhibitors to help the body swiftly eliminate dangerous cholesterol particles and lower inflammation at a time when the heart is most vulnerable to further harm. Because of this, taking it shortly after a heart attack may be very beneficial for healing the heart, lowering cholesterol and averting further issues.

Patients with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) are another significant group of patients that this study highlights. Due to issues with their cholesterol receptors, people with this genetic condition have extremely high levels of LDL (bad) cholesterol from birth. Early heart disease is far more common in people with FH. Because receptors in their bodies aren't functioning properly, many of them can't get their cholesterol down to safe levels with statins alone. PCSK9 inhibitors, on the other hand, have been demonstrated to significantly reduce LDL cholesterol, frequently assisting these patients in meeting cholesterol targets that statins alone are unable to achieve. Data from the NIH FH Registry demonstrated that PCSK9 inhibitors dramatically decreased cardiovascular event rates and enhanced LDL-C control in both heterozygous and homozygous FH patients [16]. In a pediatric case of compound heterozygous FH, where statins alone were insufficient, PCSK9 inhibitor therapy documented to be very effective [15]. The inclusion of PCSK9 inhibitors in pediatric and adult lipid management guidelines is justified by the data, which also support early and aggressive lipid-lowering interventions in genetically predisposed populations.

Even though our results are reliable and consistent, the high degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 80.2%) calls for cautious interpretation. Given the population characteristics, baseline cardiovascular risk, LDL-C levels, follow-up duration, statin intensity and outcome definitions, this heterogeneity most likely represents real variations amongst studies. For instance, some studies concentrated on real-world populations with a variety of comorbidities [14], [18] whereas some only included high-risk post-MI patients [20]. Furthermore, the level of LDL-C reduction attained differed amongst trials, with some employing PCSK9 inhibitors alone and others in conjunction with ezetimibe and high- intensity statins. Despite these variations, the use of a random-effects model is validated and worries about contradicting evidence are reduced by the consistent direction of effect across studies and the absence of any study that favors statins over PCSK9 inhibitors. The comparatively brief follow-up period in many recent studies is another drawback of our analysis. Several studies included in our review reported outcomes within 6 to 12 months, although trials like FOURIER and ODYSSEY OUTCOMES had median follow- up period of 2.2 and 2.8 years, respectively [8], [9]. The cardiovascular benefits of lowering LDL-C frequently accumulate over time [10]. Because of this, the most recent data might not fully reflect the extent of the benefit. There is still a lack of long-term safety and effectiveness data, especially for new drugs like inclisiran, a small interfering RNA that inhibits PCSK9 synthesis. To determine whether the early benefits are long-lasting and whether there are any delayed negative effects, ongoing trials with prolonged follow- up will be essential.

The broad use of PCSK9 inhibitors is practically constrained by economic factors as well. The cost is still significantly higher than that of generic statins, despite price reduction since their original release. This could restrict access in some healthcare systems. However, cost-effectiveness models indicate that in certain high-risk groups, PCSK9 inhibitors are financially feasible. Based on actual registry data, study discovered that PCSK9 inhibitors offered a respectable benefit when administered to patients with established ASCVD, whom LDL-C levels were higher than 100 mg/dL even with optimal treatment [21]. These findings highlight the significance of prudent, risk-based prescribing procedures that optimize clinical utility and reduce costs. From a translational perspective, our findings support the increasing body of evidence suggesting that LDL-C is both a causative agent in atherogenesis and a modifiable risk factor. PCSK9 inhibitors lower LDL-C to an extent that is unmatched by other treatments currently on the market, which results in proportionate decrease in the burden of atherosclerotic plaque and event risk. Additionally, ability of PCSK9 inhibitors to lower other atherogenic lipoproteins like Lp(a) provides extra therapeutic benefit, particularly for those with elevated Lp(a) who previously didn’t have access to effective therapies [17]. Because precision medicine allows for treatment to be customized based on a patient's lipid profile, genetic risk and comorbidity burden, these pleiotropic effects are becoming more and more significant. The use of PCSK9 inhibitors as part of routine treatment to reduce the risk of heart disease is generally supported by this meta-analysis, particularly for patients at high risk, who are unable to achieve their cholesterol goals with statins and ezetimibe alone. Our findings also support the use of these drugs more frequently and at an earlier age, such as in younger individuals with genetic dyslipidemias or immediately following a heart attack. Although statins remain the primary treatment, it is evident that PCSK9 inhibitors offer additional advantages that can significantly impact outcomes. This change in the way we treat heart disease and cholesterol should continue to be reflected in clinical guidelines.

Nevertheless, there are still significant questions that need to be addressed, such as the optimal time to begin treatment, the ideal cholesterol target and how well patients adhere to these regimens over time. Studying more recent drugs, such as inclisiran and small- molecule PCSK9 inhibitors, is crucial, particularly to determine their efficacy and suitability for use in countries with fewer resources. Research that focusses on actual patients, makes use of real-world data and incorporates useful clinical trials will be necessary to shape the future of cholesterol treatment. Our results unequivocally demonstrate that PCSK9 inhibitors are more effective than statins alone at lowering LDL cholesterol and risk of heart problems. These advantages apply to various population of patients and are backed by both clinical trials and real- world research. The overall evidence strongly supports the use of PCSK9 inhibitors in contemporary treatment plans, although there are still some concerns, such as the heterogeneity of study results and the length of patient follow-up. These drugs have the potential to significantly reduce heart disease globally if they are used appropriately and according to risk level of each patient.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis proved that PCSK9 inhibitors are way more effective than statins in lowering LDL-C and preventing negative cardiovascular outcomes. A variety of populations, like those with elevated lipoprotein(a), recent acute coronary syndromes, familial hypercholesterolemia or statin therapy intolerance can get benefit from PCSK9 inhibitors. They help to achieve greater and long lasting reduction in LDL-C , thus lower the risk of major cardiovascular events like myocardial infarction and stroke, which is difficult to achieve with statins alone. Hence, they should be considered vital part of lipid lowering strategy, especially in high-risk cases, where LDL-C targets remain unachieved, even with optimal statin therapy.

As time goes on, preventing heart disease will require not only effective drugs but also the intelligent and individualized application of these therapies. Future studies should concentrate on creating personal treatment programs. Overall risk of heart problems, adherence to medications and any inherited conditions like high lipoprotein levels or familial high cholesterol should all be considered. It's crucial to use PCSK9 inhibitors in patients who are most likely to benefit from them because they can be costly. Doctors may be able to predict a patient's risk and select the best course of treatment with the use of tools like fitness trackers, electronic health records and artificial intelligence. The way we treat cholesterol will continue to change as new medications like oral PCSK9 inhibitors and inclisiran become accessible. However, given the available data, PCSK9 inhibitors unquestionably mark a significant advancement in lowering the risk of heart diseases in the modern world.

References

- E Streja and KR. Feingold, “Evaluation and Treatment of Dyslipidemia in the Elderly,” in Endotext [Internet], MDText.com, Inc (2024).

- PM Ridker et al. “Rosuvastatin to Prevent Vascular Events in Men and Women with Elevated C-Reactive Protein,” Engl. J. Med 359 (2008): 2195-2207.

- Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group, “Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S),” The Lancet 344 (1994): 1383-1389.

- “MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20 536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebocontrolled trial,” The Lancet 360 (2002): 7-22.

- SM Grundy, et “AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol,” J Am Coll Cardiol 73 (2019): e285-e350.

- F Mach et al. “2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk,” Heart J vol 41 (2020): 111-188.

- Fujioka et al., “Effect of hospital Intensive lipid-lowering protocol on low density lipoprotein cholesterol control and clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction”, Accessed: Nov. 18 (2025).

- MS Sabatine et al, “Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease,” Engl. J. Med 376 (2017): 1713-1722.

- KK Ray et al. “Elevated lipoprotein(a) identifies patients with acute coronary syndrome who derive earlier and greater cardiovascular benefit of alirocumab, particularly for limb events”, Accessed: Nov. 18, (2025).

- DL Bhatt et al. “Lower rate of ischemic events with alirocumab in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease but without prior acute ischemic events”, Accessed: 18, (2025).

- Ali et al. “Early initiation of PCSK9 inhibitors in acute STEMI: Interim results of safety and efficacy from the EARLY-STEMI trial”, Accessed: Nov. 18, 2025.

- M Bonaca et al. “Abstract 4338221: EVOLocumab Very Early after Myocardial Infarction (EVOLVE-MI): A Pragmatic Randomized Multicenter International Trial - Design and Baseline Characteristics,” Circulation 152 (2025).

- J Gao et al. “Effect of PCSK9 inhibitors on the quality of life in patients with acute coronary syndromes”, Accessed: Nov. 18 (2025).

- G Ishaque et al. “Abstract 4369470: Safety and Efficacy of PCSK9 Inhibitors in Ischemic Heart Disease: An Updated Systemic Review and Meta- Analysis,” Circulation 152 (2025).

- K Zhu, F Zhang, J Wang, and C Li, “Coronary artery bypass grafting in a 14-year-old with compound heterozygous LDLR familial hypercholesterolemia: a case report,” Pediatr 13 (2025): 1625247.

- W Donaldy, M Thearle, S Shrestha, and et al. “Abstract 4343849: Assessment of Lipid-Lowering Therapy and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes in Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Insights from the NIH All Of Us Dataset,” Circulation 152 (2025): 2025.

- K Mahajan, RaMaN Puri, JB Sharma, et al. Collaborators, “Impact of elevated lipoprotein(a) on LDL-C lowering efficacy in ACS patients undergoing triple lipid-lowering therapy: insights from LAI-REACT-LP(a) sub-study”, Accessed: Nov. 18 (2025).

- R Luceri, E Ekpo, E Epstein, and D Triffon. “LDL treatment-years: a new paradigm for cardiovascular risk reduction”, Accessed: Nov. 18 (2025).

- LR Brunham, A Kramer, I Iatan, and GBJ Mancini. “Design and initial results of the Canadian lipoprotein(a) registry”, Accessed: Nov. 18 (2025).

- L Magurno, M Lang, V Pereira, and E Rodriguez. “Efficacy of PCSK9 inhibitors combined with statins versus statin monotherapy for secondary cardiovascular prevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis”, Accessed: Nov. 18 (2025).

- JL Katzmann et al. “Triple oral lipid-lowering treatment pathway and associated outcomes in high- and very high-cv risk patients: a simulation using the SANTORINI study cohort”, Accessed: Nov. 18 (2025).