A Frequent Problem in Systolic Heart Failure: Fibromyalgia

Article Information

Mehmet Ali Kobat1 ? , Ahmet karata?2

1Firat University, medical faculty hospital, Cardiology Clinic, Elazig, Turkey

2Firat University, medical faculty hospital, Rheumatology Clinic, Elazig, Turkey

*Corresponding author: Mehmet Ali Kobat, Firat University, medical faculty hospital, Cardiology Clinic, Elazig, Turkey

Received: 21 June 2021; Accepted: 05 July 2021; Published: 08 July 2021

Citation: Mehmet Ali Kobat, Ahmet karataş. A Frequent Problem in Systolic Heart Failure: Fibromyalgia. Archives of Clinical and Biomedical Research 5 (2021): 395-403.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Introduction: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is a chronic disease defined as ejection fraction (EF)<40 together with heart failure symptoms, which is progressive and has a high risk of mortality. Fibromyalgia (FM) is defined as chronic pain syndrome, characterized by widespread musculoskeletal system pain, anxiety, orthostatic hypotension, and sleep disorders, with unknown etiology. This study aimed to determine the relationship between FM with heart failure.

Material and Method: The study included 131 patients with HFrEF who described widespread body pain who presented at the Cardiology Polyclinic between January 2019 and December 2019 and 91 patients with widespread body pain and not with heart failure. All the patients were evaluated in respect of FM using the 2016 diagnostic criteria.

Results: The HFrEF group comprised 65 (49.61%) males and 66 (50.39%) females with a mean age of 67.68 ± 11.41 years and the control group comprised 43 (47.25%) males and 48 (52.75%) females with a mean age of 64.65 ± 12.62 years. The mean EF was 29.22 ± 4.04% in the HFrEF group and 60.10 ± 3.79% in the group control. A diagnosis of FM was made in 27 (20.61%) of the 131 patients with HFrEF and in 5 (5.49%) of the 91 patients control (p<0.05). When a comparison was made of patients with FM using Non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (6/27, 22.22%) and patients without FM using NSAIDs (8/181, 6.10%), it was determined that patients with FM used NSAIDs at a statistically significantly higher rate (p<0.05). A significant correlation was determined between FM and the severity of depression (p<0.05) and the depression score (p<0.05).

Conclusion: The determination of conditions that diminish the quality of life in HFrEF patients can increase their quality of life. While the diag

Keywords

Systolic Heart failure; Fibromyalgia; Depression

Article Details

1. Introduction

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is defined by the European Society of Cardiologists (ESC) as a clinical table with reduced cardiac fluid because of structural impairment, which causes increased cardiac pressure, with typical symptoms of shortness of breath, edema in the ankles and fatigue, and physical examination findings of increased jugular venous pressure, pulmonary rales and peripheral edema [1]. Prevalence in developed countries is approximately 2%. It is a severe community health problem causing morbidity and mortality throughout the world [1]. The frequency of HFrEF increases significantly with age. In the 50-59 years age range, HF is seen in 8/1000 males and this rises to 66/1000 in the 80-89 years age range, and similar rates have been reported for females [2]. With increasing life expectancy and increasing treatment options, the frequency of HF is also increasing [3]. Although great advances have been made in the understanding of the disease and treatment, HFeRF still has an extremely high mortality rate with 50% of cases dying within 5 years of the initial diagnosis [4].

Fibromyalgia (FM) is defined as a chronic pain syndrome, characterized by widespread musculoskeletal system pain, anxiety, sleep disorders, and functional symptoms, for which the etiology is unknown [5]. After osteoarthritis, FM is the most frequently seen rheumatological disease [6]. The prevalence has been reported as 3-5% and increases together with age. Between the ages of 20 and 50 years, it is seen more often in females [7]. The underlying etiology of FM has not yet been fully clarified [8]. FM is classified under the term of central sensitization. However, some studies have suggested that mechanisms related to peripheral neuropathy have a role in FM [9]. Despite the pain in soft tissues such as muscles and tendons, there are no findings of inflammation. Although widespread chronic pain is the most evident characteristic of FM, disorders such as insomnia, fatigue, headache, depression, anxiety, mood disorders, and irritable bowel syndrome often accompany FM [10, 11]. Besides, findings related to autonomous nerve system disorders such as orthostatic hypotension and changes in heart rate may also be seen in FM [12, 13]. The diagnosis of FM is made according to the 2016 FM diagnostic criteria [14]. However, as there are many problems together and there is no specific condition, FM diagnosis may generally be delayed.

Just as FM diminishes the quality of life of patients, it may also increase healthcare costs. FM may be seen as a primary disease and may also accompany another disease. Findings such as muscle pain, fatigue, listlessness, anxiety, depression and sleep disorders are often seen in patients with HFrEF. Comorbid diseases diminish the quality of life even further in HFrEF patients. The presence of FM in HF can cause a deterioration in the quality of life and impair treatment compliance. There are no data in the literature showing a relationship between the two diseases. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the frequency of FM in patients with HF.

2. Material and Method

Approval for this prospective study was granted by the Non-Invasive Research Ethics Committee of Firat University (decision no:24, dated: February 2018). All study procedures were applied in compliance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. The study included 131 patients aged >18 years, who presented at the Cardiology Polyclinic of Firat University Medical Faculty between January 2019 and December 2019, who were diagnosed with HFrEF and widespread body pain. A control group was formed of 91 patients with EF >50, no symptoms of HF, and widespread body pain. After taking the anamnesis, each patient was applied with echocardiographic examination using a Vivid™E9 with XDclear™, General Electric Medical Systems, N-3191 device (Horten, Norway) and systolic functions were evaluated.

In patients with symptoms and findings of HF and EF<40, the diagnosis of HFrEF was made based on the 2016 ESC guidelines. Patients with no symptoms and findings of HF and EF>50 were evaluated as the group control. All the patients in the study were evaluated in respect of FM using the 2016 FM diagnostic criteria. The demographic data of the patients were recorded. Comorbid diseases were determined in detail. The depressive status of the patients was evaluated using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II).

The BDI is one of the most frequently used questionnaires throughout the world as it is a reliable measurement of depressive symptoms. The BDI-II is formed of 21 items and is used in the diagnosis of depressive disorders. Each item is scored from 0 to 3, giving a possible total score of 0-63 points. High scores indicate more serious depressive symptoms. The current study patients with depression were grouped as follows; 0-9 points: minimal depressive symptoms (Group 1), 10-16 points: mild (Group 2), 17-29 points: moderate (Group 3), and 30-63 points: severe (Group 4) [15].

Patients were excluded from the study if they had HF symptoms and EF>40%, any known rheumatological disease, muscle disorder, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, neuropathic pain, multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis, a recent history of trauma, malignancy, known diagnosis of depression, a recent history of the acute coronary syndrome, or a history of major surgery within the previous 6 months.

3. Statistical Analysis

Data obtained in the study were analyzed statistically using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Chi-square test was applied to determine the relationship between HFrEF and FM, between FM and the use of NSAIDs, and between FM and depression severity. The Mann Whitney U-test was used to determine the relationship between FM and the depression score. A value of p<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

4. Results

The evaluation was made of 131 patients with HFrEF who described widespread body pain and 91 patients with widespread body pain and not with heart failure. The demographic characteristics of both groups are shown in Table 1. The drugs used and the rates of use of the HFrEF group are shown in Table 2. Comorbidities of the HFrEF group are shown in Table 3, and of the control group in Table 4.

|

HFrEF (n:131) |

Control (n:91) |

|

|

Gender (M/F) |

65/66 |

43/48 |

|

EF(%) |

29.22 ± 4.04* |

60.10 ± 3.79 |

|

Age (Years) |

67.68 ± 11.41 |

64.65 ± 12.62 |

|

FM |

27 (%20,61)* |

5 (%5.49) |

* The relationship between HFrEF and FM, Chi-square test , indicates a statistical significance (p<0.05).

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the patients.

|

Number of Patients |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

|

|

ACE/ARB inhibitors |

131 |

100 |

76.33 |

|

Beta-Blocker |

131 |

92 |

70.22 |

|

Spironolactone |

131 |

57 |

43.51 |

|

Statin |

131 |

26 |

19.84 |

|

NSAI |

131 |

10 |

7.63 |

Table 2: Drugs used and the rates in the HFrEF group.

|

Number of Patients |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

|

|

Gender (Male) |

131 |

65 |

49.61 |

|

DM |

131 |

41 |

31.29 |

|

Hypertension |

131 |

82 |

62.59 |

|

Smoking |

131 |

36 |

27.48 |

|

Ischem?c Heart Disease |

131 |

86 |

65.64 |

|

Cerebrovascular Disease |

131 |

9 |

6.87 |

|

Fibromyalgia |

131 |

27 |

20.61 |

Table 3: Comorbidities and rates in the HFrEF group.

|

Number of Patients |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

|

|

Gender (Male) |

91 |

43 |

47.25 |

|

DM |

91 |

13 |

14.28 |

|

Hypertension |

91 |

51 |

56.04 |

|

Smoking |

91 |

24 |

26.37 |

|

Ischem?c Heart Disease |

91 |

27 |

29.67 |

|

Cerebrovascular Disease |

91 |

3 |

3.29 |

|

Fibromyalgia |

91 |

5 |

5.45 |

Table 4: Comorbidities and rates in the control group.

The HFrEF group comprised 65 (49.61%) males and 66 (50.39%) females with a mean age of 67.68 ± 11.41 years and the control group comprised 43 (47.25%) males and 48 (52.75%) females with a mean age of 64.65 ± 12.62 years. The mean EF was 29.22 ± 4.04% in the HF group and 60.10 ± 3.79% in the group control, with a statistically significant difference determined between the groups (p<0.05). A statistically significantly higher rate of FM diagnosis was made in the HFrEF group as 27 (20.61%) of 131 patients, compared to 5 (5.49%) of the 91 patients control (p=0.001). When a comparison was made of patients with FM using NSAIDs (6/27, 22.22%) and patients without FM using NSAIDs (8/181, 6.10%), it was determined that patients with FM used NSAIDs at a statistically significantly higher rate (p=0.009).

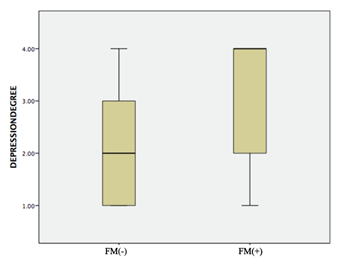

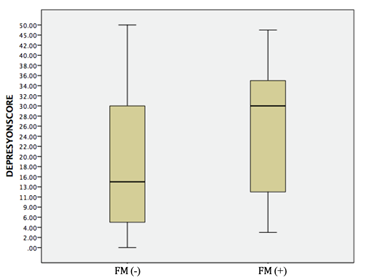

No significant difference was determined between the frequency of FM and the use of statins (p=0.502). The majority of patients without FM were in Groups 1 and 2 (101/190), 53.1%) in terms of their degree of depression, and the majority of patients with FM were in Groups 3 and 4 (23/32, 74.2%). A significant correlation was determined between FM and the degree of depression (p=0.012) (Figure 1). The median depression score was 14 (range, 0-50) in the FM group and 29.5 (range, 3-48) in the group without FM. A significant correlation was determined between FM and the depression score (p=0.003) (Figure 2).

5. Discussion

HFrEF is a progressive disease that causes frequent morbidity and mortality. Comorbidities to HFrEF can exacerbate the HFrEF and increase hospitalizations. One of the most common reasons for hospitalization of patients with HFrEF is the irregular and unnecessary use of drugs. ACE-i, ARB, beta-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, and sacubitril-valsartan used regularly and at an effective dose reduce both hospital admissions and mortality [16-18]. Compared with other chronic diseases, HFrEF has been shown to have a greater negative effect on the quality of life. General body pains are often seen in HFeEF. The quality of life status of patients with HFrEF is thought to increase hospital admissions and the mortality rate [19]. Identification, determination, and treatment of these conditions could reduce hospital admissions and mortality. One of the reasons causing a deterioration in the quality of life of HFrEF patients is widespread body pain. FM is a chronic pain syndrome seen with widespread musculoskeletal system pain and sleep disorders [5]. In the treatment of FM, specific treatments such as anti-epileptic drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are widely used. Muscle relaxants, 5HT3 receptor antagonists, dopaminergic agonists, and antioxidants may also be used. NSAIDs are not routinely recommended in FM treatment, but as NSAIDs are more easily accessible, they may often be used by patients [20, 21].

In an extensive study that scanned the healthcare systems of four different European countries, it was reported that the risk of hospitalization because of HFrEF was significantly increased with the use of traditional NSAIDs (diclofenac, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac, naproxen, nimesulide, and piroxicam) and two individual COX 2 selective NSAIDs (etoricoxib and rofecoxib) [22]. In the current study, more frequent use of NSAIDs was observed in the group with FM. Diagnosis and treatment of FM in HFrEF patients may reduce hospital admissions associated with HF exacerbation, by reducing unnecessary NSAID use and improving the quality of life of the patients [11]. The results of this study demonstrated that the frequency of depression was significantly higher in the FM group than in those without FM. The depression score was also observed to be significantly higher in patients with FM. As FM is accompanied by many additional problems and these diminish the quality of life of patients, it can be expected to lead to depressive disorders. This can cause even further deterioration in the quality of life. Therefore, FM patients should be evaluated for depression.

The frequency of FM in the HFrEF patients was determined at a statistically significantly higher rate than in the control group (p<0.05). The use of NSAIDs was also significantly higher in these patients than in the control group (p<0.05). A statistically significant correlation was determined between FM and the depression score (p<0.05) and between FM and the severity of depression (p<0.05). A limitation of this study could be said to be that there was no follow-up of the hospital admissions of the HFrEF patients with FM.

6. Conclusion

General body pains are often seen in HFrEF patients, and making a diagnosis of FM into consideration can improve quality of life with the appropriate treatment. Reducing the use of NSAIDs in HFrEF patients with comorbid FM can reduce hospital admissions. Patients with FM should be evaluated for depression, and treatments should be planned which will increase the quality of life. This study can be considered of value in respect of showing the relationship between HFrEF and FM, and between FM and the depression score and severity of depression.

Conflict of Interests

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare concerning the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

There were no specific sources of funding for this research.

References

- Ponikowski P, Voors Adriaan A, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail 18 (2016): 891-975.

- Ho KK, Pinsky JL, Kannel WB, Levy D. The epidemiology of heart failure: the Framingham Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 22 (1993): 6A-13A.

- Go AS, Moza AD, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2014 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 129 (2014): e28-e292.

- Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA, Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. The New England Journal of Medicine 360 (2009): 1418-1428.

- Arnold LM, Bennett RM, Crofford LJ, Dean LE, Clauw DJ, et al. AAPT diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. Journal of Pain (2018): 1-18.

- Blanco I, Be?ritze N, Argu?elles M, Ca?rcaba V, Ferna?ndez F, et al. Abnormal overexpression of mastocytes in skin biopsies of fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol 29 (2010): 1403-1412.

- Walitt B, Nahin RL, Katz RS, Bergman MJ, Wolfe F. The Prevalence and Characteristics of Fibromyalgia in the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. PLoS One 10 (2015): e0138024.

- Grayston R, Czanner G Elhadd K, Goebel A, Frank B, Eyler N, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of small fiber pathology in fibromyalgia: Implications for a new paradigm in fibromyalgia etiopathogenesis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 48 (2019): 933-940.

- Levine TD, Saperstein DS. Routine use of punch biopsy to diagnose small fiber neuropathy in fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol 34 (2015): 413-417.

- Choy EHS. The role of sleep in pain and fibromyalgia. A review on the role of sleep dysfunctionn as a cause and consequence of fibromyalgia; it examiness how sleep deprivation leads to abnormal pain processing. Nat Rev Rheumatol 11 (2015): 513-520.

- Alciati A, Sgiarovello P, Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P. Psychiatric problems in fibromyalgia: clinical and neurobiological links between mood disorders and fibromyalgia. Rheumatism 64 (2012): 268-274.

- Wolfe F, Smythe H, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 33 (1990): 160-172.

- Bou-Holaigah I, Calkins H, Flynn JA, et al. Provocation of hypotension and pain during upright tilt table testing in adults with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol 15 (1997): 239-246.

- Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Häuser W, et al. 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum 46 (2016): 319-329.

- Beck AT, Brown G, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory-II manual. San Antonio, Texas: The Psychological Corporation (1996).

- Dunlay SM, et al. Hospitalizations after heart failure diagnosis. a community perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol 54 (2009): 1695-1702.

- Dharmarajan K, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA (2013).

- Ziaeian B, Fonarow GC. The Prevention of Hospital Readmissions in Heart Failure Prog Cardiovasc Dis 58 (2016): 379-385.

- Heo S, Lennie TA, Okoli C, Moser DK. Quality of Life in Patients With Heart Failure: Ask the Patients, Heart Lung 38 (2009): 100-108.

- Halpern R, Shah SN, Cappelleri JC, Masters ET, Clair A. Evaluating guideline-recommended pain medication use among patients with newly diagnosed fibromyalgia. Pain Pract (2015).

- Calandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F, Slim M. An update on pharmacotherapy for the treatment of fibromyalgia. Expert Opin Pharmacother 16 (2015): 1347-1368.

- Arfè A, Scotti L, Lorenzo CV, Nicotra F, Antonella Zambon, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of heart failure in four European countries: nested case-control study BMJ (2016): 354.