A 33-Year-Old Man with Progressive Diffuse and Focal Neuropsychiatric Signs without Localizing Correlates on Brain Imaging: A Systematic Approach to Diagnosis

Article Information

Khaled Moussawi1,*, Taha Gholipour2, Vani Rao3

1National Institute on Drug Abuse, Baltimore, MD, USA

2Department of Neurology, The George Washington University, Washington, DC

3Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

*Corresponding Author: Dr. Khaled Moussawi, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 251 Bayview Blvd, Baltimore, MD 21224, United States

Received: 14 August 2020; Accepted: 21 August 2020; Published: 09 September 2020

Citation:

Khaled Moussawi, Taha Gholipour, Vani Rao. A 33-year-old Man with Progressive Diffuse and Focal Neuropsychiatric Signs without Localizing Correlates on Brain Imaging: a Systematic Approach to Diagnosis. Journal of Psychiatry and Psychiatric Disorders 4 (2020): 307-314.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Introduction: Novel expensive diagnostic tests are rapidly emerging. However, the answer to the most complex clinical presentations is often inferred from a systematic approach to the differential diagnosis. This is especially the case in neuropsychiatric disorders that present with a mix of neurologic and psychiatric symptoms. This case report fills a gap in the literature by providing a systematic differential diagnosis of such neuropsychiatric presentations associated with non-focal brain imaging.

Case Presentation: A 33-year-old African-American man presented with confusion, weakness, and tremors. He initially noted memory problems and over the following six months progressively became confused, developed speech difficulties and left sided weakness and tremors. On exam, he was predominantly abulic but with intermittent and extreme mood lability. He lacked insight and his attention was poor. He had mild facial weakness and spastic hemiparesis with action tremors on the left side. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the brain demonstrated non-specific diffuse parenchymal volume loss. His serum and cerebrospinal fluid studies were positive for Rapid Plasma Reagin and Veneral Disease Research Laboratory tests, respectively, suggesting a diagnosis of paretic neurosyphilis.

Conclusion: This is a case of a young man with neurosyphilis who presented with progressive subacute cognitive decline, associated with focal neurological signs but no focal lesions on brain imaging. Neurosyphilis is often misdiagnosed on medicine, psychiatry, and neurology inpatient units. In this report, we present an approach to conceptualize similar cases and provide a differential diagnosis that will help reach an accurate diagnosis more efficiently. Further, it raises awareness regarding neurosyphilis, a devastating but easily treatable condition.

Keywords

Dementia; Neurosyphilis; General paresis

Dementia articles, Neurosyphilis articles, General paresis articles

Dementia articles Dementia Research articles Dementia review articles Dementia PubMed articles Dementia PubMed Central articles Dementia 2023 articles Dementia 2024 articles Dementia Scopus articles Dementia impact factor journals Dementia Scopus journals Dementia PubMed journals Dementia medical journals Dementia free journals Dementia best journals Dementia top journals Dementia free medical journals Dementia famous journals Dementia Google Scholar indexed journals Neurosyphilis articles Neurosyphilis Research articles Neurosyphilis review articles Neurosyphilis PubMed articles Neurosyphilis PubMed Central articles Neurosyphilis 2023 articles Neurosyphilis 2024 articles Neurosyphilis Scopus articles Neurosyphilis impact factor journals Neurosyphilis Scopus journals Neurosyphilis PubMed journals Neurosyphilis medical journals Neurosyphilis free journals Neurosyphilis best journals Neurosyphilis top journals Neurosyphilis free medical journals Neurosyphilis famous journals Neurosyphilis Google Scholar indexed journals General paresis articles General paresis Research articles General paresis review articles General paresis PubMed articles General paresis PubMed Central articles General paresis 2023 articles General paresis 2024 articles General paresis Scopus articles General paresis impact factor journals General paresis Scopus journals General paresis PubMed journals General paresis medical journals General paresis free journals General paresis best journals General paresis top journals General paresis free medical journals General paresis famous journals General paresis Google Scholar indexed journals Montreal Cognitive Assessment test articles Montreal Cognitive Assessment test Research articles Montreal Cognitive Assessment test review articles Montreal Cognitive Assessment test PubMed articles Montreal Cognitive Assessment test PubMed Central articles Montreal Cognitive Assessment test 2023 articles Montreal Cognitive Assessment test 2024 articles Montreal Cognitive Assessment test Scopus articles Montreal Cognitive Assessment test impact factor journals Montreal Cognitive Assessment test Scopus journals Montreal Cognitive Assessment test PubMed journals Montreal Cognitive Assessment test medical journals Montreal Cognitive Assessment test free journals Montreal Cognitive Assessment test best journals Montreal Cognitive Assessment test top journals Montreal Cognitive Assessment test free medical journals Montreal Cognitive Assessment test famous journals Montreal Cognitive Assessment test Google Scholar indexed journals EEG articles EEG Research articles EEG review articles EEG PubMed articles EEG PubMed Central articles EEG 2023 articles EEG 2024 articles EEG Scopus articles EEG impact factor journals EEG Scopus journals EEG PubMed journals EEG medical journals EEG free journals EEG best journals EEG top journals EEG free medical journals EEG famous journals EEG Google Scholar indexed journals MRI articles MRI Research articles MRI review articles MRI PubMed articles MRI PubMed Central articles MRI 2023 articles MRI 2024 articles MRI Scopus articles MRI impact factor journals MRI Scopus journals MRI PubMed journals MRI medical journals MRI free journals MRI best journals MRI top journals MRI free medical journals MRI famous journals MRI Google Scholar indexed journals neurosyphilis articles neurosyphilis Research articles neurosyphilis review articles neurosyphilis PubMed articles neurosyphilis PubMed Central articles neurosyphilis 2023 articles neurosyphilis 2024 articles neurosyphilis Scopus articles neurosyphilis impact factor journals neurosyphilis Scopus journals neurosyphilis PubMed journals neurosyphilis medical journals neurosyphilis free journals neurosyphilis best journals neurosyphilis top journals neurosyphilis free medical journals neurosyphilis famous journals neurosyphilis Google Scholar indexed journals imaging articles imaging Research articles imaging review articles imaging PubMed articles imaging PubMed Central articles imaging 2023 articles imaging 2024 articles imaging Scopus articles imaging impact factor journals imaging Scopus journals imaging PubMed journals imaging medical journals imaging free journals imaging best journals imaging top journals imaging free medical journals imaging famous journals imaging Google Scholar indexed journals brain articles brain Research articles brain review articles brain PubMed articles brain PubMed Central articles brain 2023 articles brain 2024 articles brain Scopus articles brain impact factor journals brain Scopus journals brain PubMed journals brain medical journals brain free journals brain best journals brain top journals brain free medical journals brain famous journals brain Google Scholar indexed journals nervous system articles nervous system Research articles nervous system review articles nervous system PubMed articles nervous system PubMed Central articles nervous system 2023 articles nervous system 2024 articles nervous system Scopus articles nervous system impact factor journals nervous system Scopus journals nervous system PubMed journals nervous system medical journals nervous system free journals nervous system best journals nervous system top journals nervous system free medical journals nervous system famous journals nervous system Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

1. Introduction

With new knowledge and new technologies rapidly emerging, the repertoire of diagnostic tests and associated medical costs are ballooning. Further, every diagnostic test inherently carries a risk of false positives and incidental findings, which result in misdiagnoses and unnecessary further workups. This has become a challenge in fields like neurology and psychiatry, where genetic sequencing, paraneoplastic panels, and sophisticated imaging modalities are becoming routine diagnostic tests. However, the answer to the most complex clinical presentations is often inferred from a systematic approach to the differential diagnosis. This is especially the case in neuropsychiatric disorders that present with a mix of neurologic and psychiatric symptoms. This case report fills a gap in the literature by providing a systematic differential diagnosis of such neuropsychiatric presentations associated with non-focal brain imaging.

2. Case Presentation

A 33-year-old African-American male presented to the hospital with confusion, weakness, and tremors. His symptoms started six months earlier with memory impairment followed by auditory hallucinations, bizarre behavior, and grandiose delusions, for which he received neuroleptics without improvement. He gradually developed speech difficulties, unsteady gait, and left-sided tremors and weakness. He was hospitalized multiple times without a clear diagnosis, and by the time of presentation, he was withdrawn and not engaging in meaningful activities or conversations.

He was born and raised in a rural area. His birth and developmental history were unremarkable and he had no behavioral or learning problems. He lived with his wife of nine years and their two daughters who were all in good health. He had no significant past medical or psychiatric history besides his present illness and was not on any medications at the time of presentation. He smoked cigarettes daily and marijuana occasionally but denied any history of other drug use.

On exam, he was alert and calm. He appeared mostly abulic with flat affect, psychomotor slowing, and no spontaneous speech. His answers were one to two words, appropriate but unreliable. Occasionally, his abulia remitted and he became very emotional and labile. He would start crying and express feelings of hopelessness and fear of dying, but then over the course of few minutes, he would become jovial, disinhibited, his behavior puerile, and his mood expansive. He scored 13/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test (MoCA). His deficits involved multiple domains including executive, visuospatial, and memory.

On neurologic exam, he had bilateral ptosis and a mydriatic right pupil that was poorly reactive to light and accommodation. The extraocular movements were intact. He had a mild left lower facial weakness, subtle left spastic hemiparesis, and hemibody action and postural tremor of high amplitude and moderate frequency. His reflexes were diffusely brisk, though more prominently on the left. He had a present left Babinski sign. Pinprick sensation was reduced in the left leg. His gait was spastic-hemiparetic.

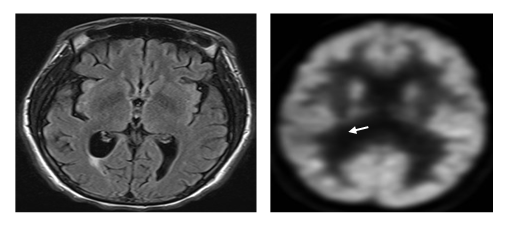

Initial workup, including complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel, was normal. Toxicology screen was positive for oxycodone and cannabinoids. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated mild diffuse parenchymal volume loss and subtle nonspecific white matter changes (Figure1, A), without abnormal focal lesions or enhancement. A brain magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) was normal.

3. Discussion

Briefly, this patient presented with rapidly progressive behavioral, emotional, and cognitive decline, associated with focal neurological signs and non-focal brain imaging. It is tempting to localize the left hemiparesis and action tremor as well as the right mydriasis to a single ventral midbrain lesion ipsilateral to the mydriatic pupil. However, the intact extraocular movements, severe encephalopathy, and non-focal brain MRI all suggest a more diffuse process. Multiple dimensions can be invoked to aid with the differential diagnosis in this case, namely 1) age-of onset, 2) time course of progression, 3) symptoms associated with the behavioral and cognitive decline, and 4) the presence of focal neurological signs in the absence of anatomically correlated findings on brain imaging.

The first dimension is the age of onset, which helps categorize the case as a young-onset dementia (i.e., patients younger than 65 years) [1]. In this age group, Alzheimer disease, vascular dementia, and frontotemporal dementia remain the most common (34%, 18%, and 12% respectively) [2]. In addition, the differential diagnosis for young onset dementias is extensive and includes other primary neurodegenerative diseases, inflammatory/autoimmune, neoplastic, infectious, metabolic, epileptic, genetic, and toxic causes. Of note, closer dementia onset to adolescence or early adulthood makes it more likely to be from genetic or metabolic causes [1].

The second dimension to invoke is the rate of progression, which places this case in the rapidly progressive dementias category. These are defined as “conditions that progress from onset of first symptom to dementia in less than one to two years” [3]. The differential diagnosis for this group is also extensive and includes neurodegenerative (including Alzheimer’s disease), vascular, inflammatory/autoimmune, neoplastic, infectious, metabolic, epileptic, genetic, and toxic causes [3]. In fact, survey of the literature reveals that the differential diagnosis for young onset and rapidly progressive dementias is very similar, almost identical [3, 4].

Another dimension is to conceptualize the case as a “dementia-plus syndrome”. This term was coined by Sampson et. al to refer to young-onset dementias where cognitive decline is associated with neurological or systemic disturbances [1]. This construct is very useful in narrowing and guiding the diagnostic investigation. Rossor et. al provide a detailed and very helpful differential diagnosis for the dementia-plus syndromes organized by neurological or systemic features [2].

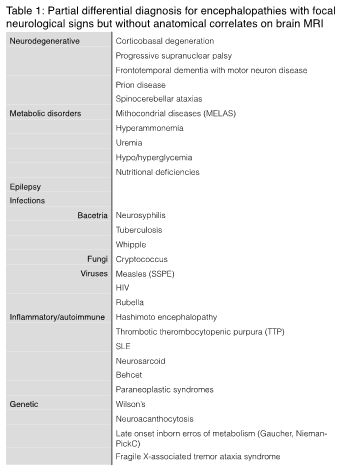

Table 1:

Finally, one can approach the case along the dimension of encephalopathies with focal neurological signs but without anatomical correlates on brain imaging. With the advances in brain imaging especially brain MRI, few encephalopathies present with focal neurological signs and non-focal MRI findings. Hence, we generated a differential diagnosis of similar presentations (Table1).

Thinking along these dimensions, and examining the differential listed in Table 1, the specific presentation of our patient (progressive encephalopathy, multiple neuropsychiatric symptoms, and focal neurological signs) raises the suspicion for certain infectious diagnoses like paretic neurosyphilis or “general paresis of the insane” [5].

Further workup, including HIV serology, ammonia, TSH, vitamin B12, and folate levels, was unremarkable. Routine EEG was normal without slowing, but brain FDG-PET scan showed cortical hypometabolism in the right parietal lobe, right inferior frontal gyrus, right insula, and bilateral temporal lobes (Figure 1, B). Treponemal antibody testing was positive, and the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) was positive at a titer of 1:128, which was diagnostic of systemic syphilis and suggestive of neurosyphilis [6]. To confirm the latter, a lumbar puncture was performed, which showed normal opening pressure, lymphocytic pleocytosis (40 WBC/mm3, 90% lymphocytes), elevated protein (75mg/dL), and positive VDRL at a titer of 1:32. These results, along with the clinical presentation, are diagnostic of paretic neurosyphilis [6,7].

Figure 1: (A) Axial brain MRI FLAIR sequence illustrating diffuse atrophy and non-specific white matter changes: (B) Brain FDG-PET scan showing cortical hypometabolism in the right parietal lobe (white arrow).

The rate of syphilis infection has been steadily increasing over the past few years, resulting in higher neurosyphilis presentations, especially in patients infected with HIV [6]. Neurosyphilis is referred to as the great imitator due to its varied presentations (neuropathy, myelopathy, meningitis, ischemic strokes, seizures, psychosis, depression, mania, anxiety, personality changes, cognitive decline, and ocular problems of any kind) [5,8,9]. It is caused by the Treponema pallidum spirochetes’ invasion of the central nervous system (neuroinvasion) which occurs early in infection [10,11]. It can be asymptomatic and clear spontaneously, or result in one or more of many clinical syndromes: 1) meningeal neurosyphilis presenting as meningitis within one year after infection; 2) vascular neurosyphilis from vasculitis of small, medium, and large vessels, presenting with ischemic strokes in the first 10 years after infection; 3) paretic neurosyphilis from brain parenchymal invasion presenting after 10-20 years; and 4) tabes dorsalis from dorsal column and spinal nerve root invasion presenting after 25-30 years [8,10].

Kraeplin in his monologue described in great detail the different neuropsychiatric manifestations of paretic neurosyphilis (general paresis) [5]. In addition to focal neurological signs and symptoms, paretic neurosyphilis most often presents with cognitive decline and myriad psychiatric symptoms including depression, mania, anxiety, delusions, hallucinations, change in behavior or personality, apathy, and irritability [5,12]. Unfortunately, recent studies indicate that paretic neurosyphilis is often missed initially in admitted patients (83-100% misdiagnosis rate) [13,14]. Initial misdiagnoses include dementia, delirium, schizophrenia, Parkinson disease, viral encephalitis, depression, mania, epilepsy, or alcohol related complications [13,14]. Brain imaging in paretic neurosyphilis is non-suggestive and usually shows diffuse cerebral atrophy and non-specific T2-hyperintensities on brain MRI [15].

Our patient was treated with intravenous penicillin per the CDC guidelines [6]. His wife tested negative for syphilis. The patient had to move out of state back to his hometown. He was lost to follow-up and did not show up for a repeat lumbar puncture 6 months after treatment to assess for therapeutic response [6]. In general, treatment of paretic neurosyphilis halts the disease progression and results in some occupational adjustment in 35-40% of patients, while 40-50% remain dependent [8].

4. Conclusion

This is a case of a young man with paretic neurosyphilis who presented with progressive encephalopathy and neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with focal neurological deficits but no correlated lesions on brain MRI. Neurosyphilis is often misdiagnosed on inpatient units, delaying treatment of this devastating but treatable disease, which is becoming increasingly prevalent. In this report, we discussed a multi-dimensional approach and provided a differential diagnosis that fills a gap in the literature regarding similar neuropsychiatric presentations.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The legally authorized representative of the patient was consented for the publication of this report.

Availability of Data and Supporting Material

Please contact corresponding author.

Funding

KM is supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA048085).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

KM and TG conceived, drafted and revised the manuscript. VR conceived and revised the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIDA.

References

- Sampson EL, Warren JD, Rossor MN. Young onset dementia. Postgrad Med J 80 (2004): 125-139.

- Rossor MN, Fox NC, Mummery CJ, et al. The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. Lancet Neurol 9 (2010): 793-806.

- Geschwind MD. Rapidly Progressive Dementia. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 22 (2016): 510-537.

- Geschwind MD, Shu H, Haman A, et al. Rapidly progressive dementia. Ann Neurol. Wiley Subscription Services, Inc., A Wiley Company 64 (2008): 97-108.

- Kraepelin E. General paresis (1913).

- Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines: syphilis. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015).

- Marra CM. Neurosyphilis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. Current Medicine Group 4 (2004): 435-440.

- Ropper A, Samuels M, Klein J. Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology 10th Edition. McGraw Hill Professional (2014).

- Gatchel J, Legesse B, Tayeb S, et al. Neurosyphilis in psychiatric practice: a case-based discussion of clinical evaluation and diagnosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 37 (2015): 459-463.

- Ghanem KG. REVIEW: Neurosyphilis: A historical perspective and review. CNS Neurosci Ther 16 (2010): e157-e168.

- Marra CM. Update on neurosyphilis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. Current Science Inc 11 (2009): 127-134.

- Rundell JR, Wise MG. Neurosyphilis: A psychiatric perspective. Psychosomatics 26 (1985): 287-295.

- Lin L-R, Zhang H-L, Huang S-J, et al. Psychiatric manifestations as primary symptom of neurosyphilis among HIV-negative patients. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. American Psychiatric AssociationArlington, VA 26 (2014): 233-240.

- Roberts MC, Emsley RA. Psychiatric manifestations of neurosyphilis. S. Afr. Med. J 82 (1992): 335-337.

- Russouw HG, Roberts MC, Emsley RA, et al. Psychiatric manifestations and magnetic resonance imaging in HIV-negative neurosyphilis. BPS 41 (1997): 467-73.