360 Health Analysis (H360) – Quality of Life of Breast Cancer Patients: an Integrated Vision

Article Information

Patrícia Miguel Semedo1,2, Sara Coelho1,3, Ines Brandão Rego1,4, Joana Cavaco-Silva1,5*, Laetitia Teixeira1,6, Susana Sousa1,6, Francisco Pavão1, Ricardo Baptista Leite1,7, Luis Costa1,2

1Institute of Health Sciences, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal

2Hospital de Santa Maria, Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte, Portugal

3Instituto Português de Oncologia do Porto Francisco Gentil EPE, Portugal

4Centro Hospitalar Universitário São João EPE, Portugal

5ScienceCircle - Scientific and Biomedical Consulting, Portugal

6Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas Abel Salazar, Universidade do Porto, Portugal

7Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Portugal

*Corresponding author: Joana Cavaco-Silva, ScienceCircle - Scientific and Biomedical Consulting, Portugal.

Received: 25 March 2023; Accepted: 04 April 2023; Published: 20 April 2023

Citation: Patrícia Miguel Semedo, Sara Coelho, Inês Brandão Rêgo, Joana Cavaco-Silva, Laetitia Teixeira, Susana Sousa, Francisco Pavão, Ricardo Baptista Leite, Luís Costa. 360 Health Analysis (H360) – Quality of Life of Breast Cancer Patients: an Integrated Vision. Archives of Clinical and Biomedical Research. 7 (2023): 262-274.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: This study is part of the H360 Health Analysis (H360) and aimed to investigate the Quality of Life (QoL) of Breast Cancer (BC) patients in the real world.

Methods: Two questionnaires (EORTC QLQ?C30 version 3.0 and its breast-specific module QLQ?BR23) validated for the Portuguese population were applied to assess BC patients’ QoL in seven Portuguese hospitals.

Results: BC was diagnosed in early stage in 68%, in locally advanced stage in 5%, and in advanced stage in 22% of patients. Patients’ median age was 59 years (range 35-85). Most (97%) received surgery for the primary tumor, 27% radiotherapy, 24% chemotherapy, 15% endocrine therapy, and 6% targeted therapy. Women who completed the survey reported a mean overall health rate of 4.9 and a mean QoL rate of 5 on a 7-point Likert-type scale. Some degree of impairment in strenuous activities or taking long walks was reported by 84% and 64% of women, respectively. Negative psychological impact was reported by 71%. Pain was the most frequent symptom (57%), interfering with daily activities for 46% of women. Work and daily activities were impaired in 56%, social activities in 23%, and family activities in 26% of BC patients, with 34% reporting financial difficulties.

Conclusions: Adequate support and strategies are required to address the clinical, physical, and psychosocial needs of BC survivors. This study reinforces the need to refer these patients to appropriate interventions (as psycho-oncological and social support), develop a framework for work alternatives, and promote a more active lifestyle.

Keywords

Breast cancer; Quality of life; Healthcare system; Survivorship

Breast cancer articles; Quality of life articles; Healthcare system articles; Survivorship articles

Article Details

Introduction

According to the latest GLOBOCAN report, around 19.3 million new cancer diagnoses and 9.9 million cancer deaths were reported in 2020, with the first expected to increase to 28.4 million (equivalent to a 47% rise) by 2040 [1]. Female breast cancer (BC) surpassed lung cancer as the most diagnosed cancer that year, with an estimated 2.3 million new cases (11.7%) reported [2]. In Portugal, BC was the second most incident malignancy in 2020 after colorectal cancer in both sexes and all ages combined (7041 new cases; 11.6%), but by far the most incident in females (26.4% of all cancer diagnoses) [3]. with BC becoming a largely curable disease, the proportion of long survivors is also increasing. According to the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), more than 70% of women currently survive at least 10 years after diagnosis across most European countries due to early detection and treatment [4], and according to the American Cancer Society, there are currently more than 3.8 million BC survivors in the United States, including women still under treatment and who have completed treatment [5].

BC is a highly heterogeneous disease, with a plethora of clinical presentations, and one of the cancers with the greatest availability of therapeutic options in its different stages [6]. Differences in sociodemographic background, comorbidities, physiological characteristics, and family and community all contribute to the way these patients experience their disease and treatments [7]. The growing prevalence of BC survivors is closely associated with improvements in early disease detection and treatment. Although historically the research has focused on BC survivors after primary treatment [8], an evidence-based framework for assessing the quality of cancer survivorship care has been recently developed, aiming to provide coordinated and comprehensive support for cancer survivors in the domains of clinical care, research, and policy [9]. This framework proposes five main components that should be considered in the survivorship care pathway: 1) prevention and surveillance of recurrences and new cancers; surveillance and management of 2) physical and 3) psychosocial effects and of 4) chronic medical conditions; and 5) health promotion and disease prevention [9]. Despite the potential benefit of these care plans due to their multidisciplinary nature, cancer centers still struggle with the implementation of all its components. Current challenges include education on long-term and late effects of cancer treatment and comorbidities, a change in paradigm for shifting the management of survivorship care away from oncologists, and patients’ health literacy and engagement to self-manage their care [10]. It is acknowledged that BC is transformative for patients, not just physiologically but also socio-behaviorally. It is crucial to recognize and understand the difficulties and needs of these patients, as a substantial proportion live with troublesome symptom burden that negatively impacts treatment adherence and post-treatment overall quality of life (QoL) [11–15]. Several observational studies have sought to describe the range of symptoms that women experience since cancer diagnosis. At the moment of diagnosis, patients cope with different emotions and feelings when faced with the disease process. It is a moment of emotional distress in view of the unknown, changes in daily life, and treatment planning, with anxiety levels reaching 19% in the general cancer population [12]. During the active treatment phase, acute symptoms experienced include fatigue, pain, hair loss, and changes in physical function, but these gradually resolve in the year after the primary surgery or at the end of radiation or adjuvant chemotherapy [11,13–15]. Conversely, other less acute symptoms persist for many years after treatment conclusion, including menopausal symptoms, cognitive complaints, fatigue, mood disturbances, and changes in sleep and exercise [16, 17]. Survivorship data from the French CANcer TOxicities (CANTO) study showed that 50% of patients suffered from at least one severe post-treatment symptom, over 30% reported high emotional or social dysfunction, and over 20% struggled to return to the workplace after cancer diagnosis [18,19]. Side effects are also a major driver of treatment discontinuation and poor compliance, leading to increased risk of recurrence. To balance treatment adherence with QoL preservation, efforts should be made to identify what the real treatment toxicities are and implement strategies to mitigate them, as this can have an impact on survival outcomes. Overall, despite the availability of disease-specific survivorship care guidelines [20], which recommend routine screening and treatment of psychological distress as quality standards across the cancer care trajectory [21], optimal survivorship care is still not adequately delivered in the clinical practice of BC patients.

Study rationale

With the improvements in overall survival and disease?free survival seen with the implementation of screening programs and availability of new treatment options, QoL emerged as a relevant concern in the management of BC patients and survivors [6]. In fact, QoL is increasingly acknowledged as a treatment goal on its own, with its importance and need for assessment recognized in the European Consensus Guidelines for Advanced Breast Cancer [22] and incorporated in the ESMO Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale [23] for new cancer therapies. However, the application of QoL questionnaires is mainly performed in clinical trial setting, and their routine use in the clinical practice in Portugal is still inconsistent and generally scarce. Given the lack of evidence-based, real-world data regarding the management of BC patients in Portugal, 360 Health Analysis (H360) was developed as a multiphase, multicenter project with the aim of providing a comprehensive picture of BC management in the country by retrieving real-world data from national hospitals. A pool of hospitals including general (university and regional) hospitals and Oncology centers from the public and private sectors was included. H360 Phase 1 consisted of a literature review of the subject [24], and the ongoing Phase 2 intends to assess the performance of the Portuguese health system in BC management [25]. The present study, part of H360 Phase 2 – Stage B, aims to provide an overview of BC patients’ QoL at national level. The final goal of H360 is to put forward a national consensus with an action plan on how to improve the management of BC patients in Portugal.

Material and Methods

This was a quantitative, cross-sectional, descriptive study based on a voluntary survey conducted to BC patients in the study hospitals between June 1 and 23, 2020. A total of seven hospitals (1 general university hospital, 3 district hospitals, 2 Oncology centers, and 1 private hospital) were included in the project, as detailed in Coelho S et al. 2021 [25]. Patients were eligible to participate if they were women with ≥18 years of age, histologically confirmed breast cancer for ≥6 months and £5 years, a first cancer diagnosis, able to understand, sign, and date written informed consent prior to any protocol-specific procedure, and capable of answering the survey questions. No exclusion criteria were set. The sampling was randomly conducted by study investigators as patients attended the Oncology consultation. During the appointment, they were invited to participate by the doctor and signed informed consent in case of positive response. The interviews were conducted by an independent external partner, either online using the Computer Assisted Web Interview (CAWI) system or by telephone contact using the Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI) system. Three sets of questionnaires were applied in this study. The first consisted of general questions about participants’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, specifically age, geographic area of residency, treatment hospital, household composition, marital status, net monthly income of the household, disease stage, time since diagnosis, and treatment modalities. In addition, two cancer-specific questionnaires were also applied: the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer 30-Item QOL Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) version 3.0 [26–28] and its BC-specific module QLQ-BR23 [29,30]. The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a 30-item self-reported questionnaire covering functional (global health status, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, and social functioning) and symptom-related (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, and financial difficulties) aspects of QoL in cancer patients. The validity and reliability of the Portuguese version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 have been confirmed [27]. EORTC QLQ-BR23 comprises 23 questions covering aspects such as body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment, future perspective, systemic therapy side effects, breast symptoms, arm symptoms, and distress due to hair loss.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculations for this analysis are reported elsewhere [25].

The scoring of EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 was performed as per EORTC scoring manual procedures [30–32]. All mean scores were linearly transformed into a scale from 0 and 100, with 0 representing the worst and 100 the best health status. The symptom scale is an exception to this rule, as the higher score represents a higher symptom burden and thus the worst health status. Median and interquartile range were reported for continuous variables, and frequencies for categorical variables. To compare categorical variables among groups, χ2 and Fisher exact tests were used whenever appropriate. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare medians. Student’s t-test was used to compare two groups, and one-way analysis of variance was used in cases of more than two groups. To assess the effect of the parameters analyzed, univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted using binary logistic regression. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was assumed when the p-value was inferior to 0.05. All analyses were computed in IBM’s SPSS statistics v.24.

Results

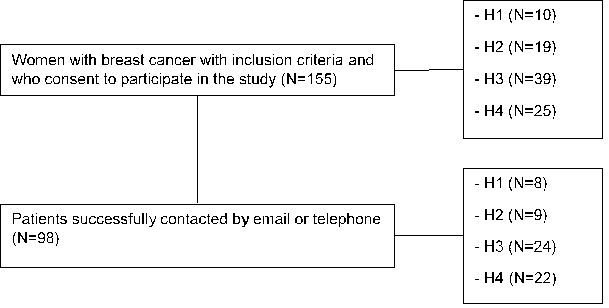

A total of 155 women with BC consent to participate in the study. Of these, 98 were successfully contacted, either by email or telephone, comprising the final study population. Figure 1 depicts the flowchart of patient enrollment in the study.

The median age of the study population was 59 (range 35−85) years, and most patients lived in the north of Portugal (33%) and Lisbon (32%). Patients’ households mostly comprised two people (44%), followed by three (23%) and four or more (13%) people, with 20% of patients living alone. A significant proportion of women (58%) were married or lived with a partner, 16% were single, 13% were divorced, and 13% were widows. The predominant net monthly income of the household was below 800€ (30%), followed by 800−1200€ (23%). The sociodemographic characteristics of the study population are further detailed in (Table 1).

Table 1: Sociodemographic and disease characteristics of the study population.

|

Geographic area of residency |

n (%) |

|

North |

32 (33) |

|

Center |

10 (10) |

|

Lisbon |

31 (32) |

|

Alentejo* |

12 (12) |

|

Algarve* |

13 (13) |

|

Hospital |

n (%) |

|

H1 |

8 (8) |

|

H2 |

9 (9) |

|

H3 |

22 (23) |

|

H4 |

24 (25) |

|

H5 |

9 (9) |

|

H6 |

14 (14) |

|

H7 |

12 (12) |

|

Household composition |

n (%) |

|

1 |

20 (20) |

|

2 |

43 (44) |

|

3 |

22 (23) |

|

≥4 |

13 (13) |

|

Marital status |

n (%) |

|

Single |

15 (16) |

|

Married or living with a partner |

57 (58) |

|

Divorced |

13 (13) |

|

Widow |

13 (13) |

|

Net monthly income of the household |

n (%) |

|

≤800€ |

19 (19) |

|

800−1200€ |

15 (15) |

|

1201−1600€ |

9 (9) |

|

1601−2000€ |

3 (5) |

|

2001−2400€ |

6 (6) |

|

≥2401€ |

12 (12) |

|

NR |

34 (34) |

|

Disease stage |

n (%) |

|

Early stage |

67 (68) |

|

Locally advanced |

5 (5) |

|

Metastatic |

21 (22) |

|

NR |

5 (5) |

|

*Southern provinces of Portugal |

|

Most women (53%) had been diagnosed with BC for less than 4 years, with the remaining (42%) diagnosed for 4 years or more. Regarding disease stage, early-stage BC prevailed in this sample of patients (68%), followed by metastatic (22%) and locally advanced (5%) BC. Five percent of patients were unaware of their disease stage (Table 1). Twenty-eight percent of women under the age of 60 and 13% of women with or over the age of 60 years had metastatic disease.

Treatment characteristics

The study population had an average time on BC treatment of 3.9 years, with 38% undergoing treatment at the time of the survey. Almost all patients (97%) underwent surgery for the primary tumor (48% total mastectomy, 44% conservative surgery, 8% did not know/respond), 27% radiotherapy, 24% chemotherapy, 15% endocrine therapy, and 6% targeted therapy. Only a minority of patients (4%) had participated in a clinical trial. The large majority of patients (98%) underwent regular surveillance for the primary tumor after undergoing treatment with curative intent, with 16% of these cases presenting with BC recurrence after surgery. Among patients with disease relapse, 86.6% underwent systemic palliative treatment (2 patients did not respond to this question). Total mastectomy was the main surgical procedure in women less than 60 years old (69.6%), whereas breast-conservative surgery was the main surgical procedure in older women (51.2%). Among women who underwent surgery for the primary tumor, 31% underwent neoadjuvant treatment and 95% adjuvant treatment. Significantly more patients below the age of 60 received neoadjuvant treatment compared to older patients (41% vs. 16%; p=0.026). The most frequent adjuvant treatment was radiotherapy (77%), followed by chemotherapy (67%) and endocrine therapy (27%).

Quality of life assessment

EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3)

According to EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3) questionnaire, BC and its treatments had a considerable impact on patients’ QoL (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). A relevant 84% (n=82) and 64% (n=63) of women experienced at least some difficulty in performing strenuous activities (like carrying a heavy shopping bag or suitcase) and taking a long walk, respectively, with 38% and 20% reporting severe difficulties in these activities. On the other hand, 61% (n=60) of women experienced no difficulties in taking a short walk outside the house, and most did not feel the need to stay in bed or chair during the day (81%; n=82) or have help eating, dressing, washing, or using the toilet (94%; n=92). Regarding emotional and cognitive functioning, the negative psychological impact of the disease was the most mentioned by patients, with 71% feeling some degree of worry, 67% having difficulty remembering things, 57% feeling irritable, and 47% feeling depressed. Difficulty sleeping and tiredness were also common symptoms (66% and 57%, respectively). Pain was the most frequent symptom over the last week (57%), interfering with daily activities in 46% of cases. This symptom was more often reported in metastatic compared to early disease setting (41.3% vs. 22.2%). Other physical symptoms included constipation (24%), anorexia (19%), dyspnea (17%), nausea (9%), diarrhea (9%), and vomiting (7%).

Importantly, complaints related to family and social life were also frequently reported. A total of 23% of patients admitted that their physical condition or medical treatment interfered with social activities, and for 26% it interfered with family life. Professional life was also affected by the disease for 56% of patients, who felt limited in performing their work duties or other daily activities. Leisure was also impaired, with 49% of patients feeling limited in pursuing their hobbies or interests and 46% reporting that pain interfered with daily activities.

Around one-third of patients (34%) acknowledged financial difficulties associated with their physical condition or treatment.The global health status of patients was generally good, with a mean overall health rate of 4.9 and a mean QoL rate of 5 on a 7-point Likert-type scale.

EORTC QLQ-BR23

The application of the EORTC QLQ-BR23 questionnaire, concerning patients’ self-assessment of their body image, showed that most women did not feel physically less attractive (68%), had no difficulty looking at their naked body (69%), and did not feel less feminine (70%) as a result of the disease or its treatments (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Concern about the future was the main worry for these patients (80%), with 12% reporting great concern. Regarding sexuality, most women had not been sexually active (71%) or felt sexual desire (72%) in the previous four weeks. Among those who were sexually active, 3 out of 4 had no enjoyment in sexual intercourse. A relevant proportion of patients experienced local symptoms related to BC or its treatments. More than half (58%) experienced pain in the arm or shoulder, 32% hand or arm edema, 48% difficulty raising the arm, 42% pain in the affected breast area, and 11% edema in the affected breast area.

Quality of life by patient subgroup

Age

QoL according to age (<60 vs. ≥60 years old) is depicted in Table 2. Younger BC patients (<60 years old) reported significantly worse social functioning (p=0.001) and were less happy with body image (p=0.026) and more upset by hair loss (p=0.025). On the other hand, they reported better sexual functioning (p=0.002).

Table 2: EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 scores by age.

|

<60 years |

≥60 years |

p-value |

|||

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||

|

QLQ-C30 |

|||||

|

Global health status |

65.2 |

24.1 |

66.3 |

22.7 |

0.83 |

|

Functional scales |

|||||

|

Physical functioning |

74.7 |

19.2 |

73.3 |

20.8 |

0.732 |

|

Role functioning |

74.6 |

26.2 |

77.1 |

24.9 |

0.635 |

|

Emotional functioning |

73.5 |

20.5 |

75.4 |

18.4 |

0.644 |

|

Cognitive functioning |

74 |

27.3 |

81.3 |

18.9 |

0.125 |

|

Social functioning |

82.2 |

26.5 |

96.3 |

11 |

0.001 |

|

Symptom scales |

|||||

|

Fatigue |

27.5 |

25.7 |

21.4 |

20.8 |

0.201 |

|

Nausea and vomiting |

4.1 |

11.5 |

2.5 |

11.7 |

0.505 |

|

Pain |

24.9 |

24.8 |

26.7 |

32.4 |

0.767 |

|

Dyspnea |

6.4 |

16 |

9.2 |

21.3 |

0.472 |

|

Insomnia |

40.9 |

32.7 |

33.3 |

35.4 |

0.279 |

|

Appetite loss |

9.4 |

20.7 |

10.8 |

26.6 |

0.759 |

|

Constipation |

11.1 |

19.2 |

5.8 |

12.8 |

0.109 |

|

Diarrhea |

2.9 |

11.4 |

5.8 |

18.3 |

0.338 |

|

Financial difficulties |

18.1 |

26 |

16.7 |

32.9 |

0.808 |

|

QLQ-BR23 |

|||||

|

Functional scales |

|||||

|

Body image |

79.2 |

23.5 |

89.6 |

19.9 |

0.026 |

|

Sexual functioning |

15.2 |

19.2 |

4.6 |

13.1 |

0.002 |

|

Sexual enjoyment |

39.1 |

19.2 |

33.3 |

23.6 |

0.561 |

|

Future perspective |

50.9 |

30.9 |

62.5 |

30.4 |

0.07 |

|

Symptom scales |

|||||

|

Systemic therapy side effects |

17 |

16.3 |

12.6 |

14.8 |

0.176 |

|

Breast symptoms |

14.6 |

17.1 |

8.5 |

14.1 |

0.068 |

|

Arm symptoms |

23 |

21.8 |

25.8 |

27.7 |

0.575 |

|

Upset by hair loss |

11.1 |

16.7 |

44.4 |

34.4 |

0.025 |

|

SD, standard deviation |

|||||

Socioeconomic status

Supplementary Table 5 depicts QoL scores according to monthly household income (≤1200€, 1201-2000€ and >2000€). Low income (≤1200€) was associated with worse physical functioning (p=0.002) and greater financial difficulties (p=0.029) compared to higher monthly income (>2000€). However, only the differences between a monthly household income ≤1200€ and >2000€ were significant.

Disease stage

The stage of BC affected women’s QoL, with women with advanced disease experiencing poorer global health status (p=0.008), physical functioning (p=0.003), role functioning (p=0.013), and cognitive functioning (p=0.0012), and higher levels of pain (p=0.006) and systemic therapy side effects (p=0.023) compared to women in earlier stages of disease (Table 3). On the other hand, advanced disease stage was not significantly associated with worse symptoms (other than pain) or worse sexual functioning/enjoyment, and also did not influence patients’ future perspective.

Table 3: EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 scores by disease stage.

|

Localized and locally advanced BC |

Metastatic BC |

p-value |

||||

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

|||

|

QLQ-C30 |

||||||

|

Global health status |

70 |

19.4 |

50 |

30.2 |

0.008 |

|

|

Functional scales |

||||||

|

Physical functioning |

76.9 |

17.7 |

62.9 |

22.5 |

0.003 |

|

|

Role functioning |

78.5 |

23 |

62.7 |

31.1 |

0.013 |

|

|

Emotional functioning |

75.3 |

19.8 |

65.9 |

22 |

0.063 |

|

|

Cognitive functioning |

80.1 |

21.4 |

65.1 |

29.8 |

0.012 |

|

|

Social functioning |

90.3 |

20.9 |

81 |

25.4 |

0.09 |

|

|

Symptom scales |

||||||

|

Fatigue |

23.1 |

21.6 |

35.4 |

29.5 |

0.087 |

|

|

Nausea and vomiting |

1.9 |

6.6 |

9.5 |

20.8 |

0.11 |

|

|

Pain |

22.2 |

26.7 |

41.3 |

30.1 |

0.006 |

|

|

Dyspnea |

6 |

18 |

12.7 |

19.7 |

0.146 |

|

|

Insomnia |

36.1 |

33.5 |

47.6 |

34.3 |

0.171 |

|

|

Appetite loss |

8.8 |

21.7 |

12.7 |

26.8 |

0.494 |

|

|

Constipation |

9.3 |

18.7 |

11.1 |

16.1 |

0.682 |

|

|

Diarrhea |

2.8 |

9.3 |

9.5 |

26.1 |

0.258 |

|

|

Financial difficulties |

16.2 |

29.1 |

23.8 |

30.1 |

0.298 |

|

|

QLQ-BR23 |

||||||

|

Functional scales |

||||||

|

Body image |

83.8 |

23.1 |

82.5 |

21.7 |

0.825 |

|

|

Sexual functioning |

8.8 |

17.2 |

15.1 |

14.8 |

0.134 |

|

|

Sexual enjoyment |

41.2 |

18.7 |

29.6 |

20 |

0.157 |

|

|

Future perspective |

56 |

30.6 |

52.4 |

34.3 |

0.642 |

|

|

Symptom scales |

||||||

|

Systemic therapy side effects |

13.4 |

13.9 |

22.4 |

20.9 |

0.023 |

|

|

Breast symptoms |

11.1 |

16.3 |

15.5 |

16.7 |

0.285 |

|

|

Arm symptoms |

22.2 |

24.2 |

30.7 |

25.8 |

0.169 |

|

|

Upset by hair loss |

23.1 |

28.5 |

22.2 |

38.5 |

0.965 |

|

|

BC, breast cancer; SD, standard deviation |

||||||

Treatment modality

Regarding the type of breast surgery, women who underwent mastectomy had better QoL in terms of symptoms as dyspnea (p=0.017) and loss of appetite (p=0.033), financial difficulties (p=0.048), and sexual enjoyment (p=0.035; Table 4). On the other hand, they were more upset about hair loss (p=0.035).Patients not submitted to radiotherapy had better global health status than those who did (p=0.046). On the other hand, no differences were found in breast or arm symptoms (Supplementary Table 6). Considering women submitted to chemotherapy, and regardless of the setting (neoadjuvant/adjuvant), these experienced significantly more nausea and vomiting (p=0.006), with no significant differences in the remaining aspects assessed (Table 5). Women treated with endocrine therapy were less upset by hair loss (p=0.016) and suffered less from constipation than those not receiving endocrine therapy (p=0.031; Table 6).

Table 4: EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 scores by type of breast surgery.

|

Type of breast surgery |

p-value |

||||

|

Mastectomy |

Conservative surgery |

||||

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||

|

QLQ-C30 |

|||||

|

Global health status |

67.9 |

21.8 |

62.3 |

25.8 |

0.271 |

|

Functional scales |

|||||

|

Physical functioning |

74.8 |

18.4 |

74.4 |

21.9 |

0.943 |

|

Role functioning |

80.9 |

23.8 |

71.8 |

26.9 |

0.097 |

|

Emotional functioning |

76.8 |

20.5 |

70.4 |

18.2 |

0.129 |

|

Cognitive functioning |

78.7 |

22.7 |

75 |

27.1 |

0.483 |

|

Social functioning |

86.9 |

23.6 |

87.7 |

23.3 |

0.87 |

|

Symptom scales |

|||||

|

Fatigue |

19.9 |

21.5 |

29.4 |

26.1 |

0.063 |

|

Nausea and vomiting |

3.5 |

12 |

4 |

12.1 |

0.869 |

|

Pain |

23 |

24.2 |

28.6 |

31.5 |

0.354 |

|

Dyspnea |

2.1 |

8.2 |

10.3 |

20.1 |

0.017 |

|

Insomnia |

36.2 |

30.2 |

39.7 |

36.2 |

0.623 |

|

Appetite loss |

4.3 |

13.2 |

15.1 |

29.6 |

0.033 |

|

Constipation |

6.4 |

16.5 |

10.3 |

17.2 |

0.275 |

|

Diarrhea |

5.7 |

17.5 |

3.2 |

12.3 |

0.443 |

|

Financial difficulties |

12.8 |

25.6 |

25.4 |

32.8 |

0.048 |

|

QLQ-BR23 |

|||||

|

Functional scales |

|||||

|

Body image |

78.9 |

24 |

87.9 |

20.3 |

0.061 |

|

Sexual functioning |

14.2 |

20.6 |

7.1 |

13.3 |

0.056 |

|

Sexual enjoyment |

43.1 |

19.6 |

29.6 |

11.1 |

0.035 |

|

Future perspective |

60.3 |

30 |

47.6 |

31.4 |

0.055 |

|

Symptom scales |

|||||

|

Systematic therapy side effects |

13.7 |

12.8 |

16.1 |

18.6 |

0.482 |

|

Breast symptoms |

10.3 |

12.6 |

14.7 |

20.2 |

0.228 |

|

Arm symptoms |

22.2 |

21.9 |

25.4 |

25.4 |

0.528 |

|

Upset by hair loss |

44.4 |

34.4 |

9.5 |

16.3 |

0.035 |

|

SD, standard deviation |

|||||

Table 5: EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 scores by chemotherapy as treatment modality.

|

Chemotherapy |

p-value |

||||

|

No |

Yes |

||||

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||

|

QLQ-C30 |

|||||

|

Global health status |

73.7 |

18.7 |

63.7 |

24.4 |

0.099 |

|

Functional scales |

|||||

|

Physical functioning |

79.3 |

19.7 |

73.3 |

19.7 |

0.242 |

|

Role functioning |

82.5 |

23.2 |

74.6 |

26 |

0.231 |

|

Emotional functioning |

72.4 |

23.4 |

74.1 |

19.7 |

0.739 |

|

Cognitive functioning |

84.2 |

18.8 |

75.2 |

25 |

0.147 |

|

Social functioning |

89.5 |

25.6 |

87.5 |

22.1 |

0.737 |

|

Symptom scales |

|||||

|

Fatigue |

21.1 |

21.6 |

25 |

23.9 |

0.514 |

|

Nausea and vomiting |

0 |

0 |

4.2 |

12.8 |

0.006 |

|

Pain |

24.6 |

29.6 |

25.7 |

27.1 |

0.877 |

|

Dyspnea |

7 |

14 |

6.1 |

16.1 |

0.828 |

|

Insomnia |

35.1 |

34.2 |

38.2 |

33.4 |

0.722 |

|

Appetite loss |

12.3 |

27.7 |

8.3 |

21.2 |

0.497 |

|

Constipation |

8.8 |

18.7 |

9.2 |

17.7 |

0.924 |

|

Diarrhea |

1.8 |

7.6 |

4.8 |

16.1 |

0.421 |

|

Financial difficulties |

15.8 |

32.1 |

19.7 |

29.9 |

0.613 |

|

QLQ-BR23 |

|||||

|

Functional scales |

|||||

|

Body image |

85.1 |

23.2 |

82.7 |

22.7 |

0.681 |

|

Sexual functioning |

8.8 |

16.1 |

11.2 |

18.1 |

0.598 |

|

Sexual enjoyment |

33.3 |

23.6 |

39.4 |

19.6 |

0.552 |

|

Future perspective |

52.6 |

30.1 |

55.7 |

31.5 |

0.702 |

|

Symptom scales |

|||||

|

Systematic therapy side effects |

13.5 |

14 |

15.5 |

16.2 |

0.633 |

|

Breast symptoms |

11.8 |

16.7 |

11.8 |

16.3 |

1 |

|

Arm symptoms |

20.5 |

27.8 |

23.8 |

22.3 |

0.578 |

|

Upset by hair loss |

11.1 |

19.2 |

27.3 |

32.7 |

0.437 |

|

SD, standard deviation |

|||||

Table 6: EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 scores by endocrine therapy as treatment modality.

|

Endocrine therapy |

p-value |

||||

|

No |

Yes |

||||

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||

|

QLQ-C30 |

|||||

|

Global Health Status |

65.9 |

21.6 |

65.3 |

28.5 |

0.913 |

|

Functional scales |

|||||

|

Physical functioning |

74.9 |

18.3 |

72.5 |

23.9 |

0.612 |

|

Role functioning |

76.6 |

24.7 |

73.6 |

28.6 |

0.624 |

|

Emotional functioning |

74.1 |

21.2 |

72.6 |

17.6 |

0.75 |

|

Cognitive functioning |

76.8 |

24.5 |

77.1 |

24 |

0.961 |

|

Social functioning |

90.1 |

20.4 |

81.9 |

27.3 |

0.123 |

|

Symptom scales |

|||||

|

Fatigue |

24.5 |

23.3 |

26.9 |

25.6 |

0.673 |

|

Nausea and vomiting |

1.8 |

8.1 |

8.3 |

17.7 |

0.092 |

|

Pain |

27.3 |

30.2 |

22.2 |

21.2 |

0.371 |

|

Dyspnea |

7.2 |

18.5 |

8.3 |

17.7 |

0.794 |

|

Insomnia |

37.8 |

33.3 |

37.5 |

35.9 |

0.966 |

|

Appetite loss |

8.1 |

21.2 |

15.3 |

27.8 |

0.255 |

|

Constipation |

11.3 |

19.3 |

4.2 |

11.3 |

0.031 |

|

Diarrhea |

3.2 |

11.3 |

6.9 |

21.9 |

0.423 |

|

Financial difficulties |

20.3 |

30.6 |

12.5 |

27.5 |

0.271 |

|

QLQ-BR23 |

|||||

|

Functional scales |

|||||

|

Body image |

85.7 |

20.9 |

77.4 |

85.7 |

0.119 |

|

Sexual functioning |

9.7 |

17 |

13.9 |

9.7 |

0.312 |

|

Sexual enjoyment |

35.1 |

20.7 |

44.4 |

35.1 |

0.248 |

|

Future perspective |

56.3 |

32.6 |

51.4 |

56.3 |

0.508 |

|

Symptom scales |

|||||

|

Systemic therapy side effects |

13.9 |

14.8 |

20.4 |

13.9 |

0.081 |

|

Breast symptoms |

11.8 |

16.8 |

12.5 |

11.8 |

0.859 |

|

Arm symptoms |

23.3 |

24.5 |

25.9 |

23.3 |

0.645 |

|

Upset by hair loss |

10 |

16.1 |

44.4 |

10 |

0.016 |

|

SD, standard deviation |

|||||

Discussion

With breast cancer becoming a largely curable disease and a substantial proportion of patients becoming long survivors, much due to early detection programs and increased treatment effectiveness, QoL after cancer has evolved to be one of the cornerstones of the patient journey. However, the current follow-up standards fall short of adequately addressing this crucial aspect of patients’ management. According to a study presented at the ESMO Breast Cancer Virtual Congress 2021, BC survivors widely differ in the burden of symptoms they experience after the end of treatment, and therefore post-treatment care should be tailored to address each survivor’s unique experiences and needs [33]. The evidence in the literature is scarce regarding the management and quality of care of BC in Portugal [24]. Since real-world data is necessary to assess and improve the outcomes of these patients, H360 intended to address this unmet need by providing a comprehensive, overall picture of BC management in the country. One of its fundamental aspects is patients’ QoL, which the present study sought to investigate. The authors applied two of the most widely used instruments for assessing health-related QoL in patients with cancer, EORTC QLQ-C30 and its specific BC module QLQ-BR23, as several studies have validated and employed these scales and they are also validated in Portugal [27, 34–38]. Women’s global health status was good, with a mean overall health rate of 4.9 and a mean QoL rate of 5 on a 7-point Likert-type scale. However, similarly to previous studies, some level of impairment was seen in strenuous activities (reported by 84% of women) or taking a long walk (reported by 64% of women) [37,39]. Psychosocial effects were among the most reported by BC patients, with 71% experiencing some degree of concern, 67% having difficulty remembering things, 57% feeling irritability, and 47% reporting feelings of depression. This percentage of psychosocial effects is higher than what had been described in French studies (around 30%) [11,19]. The difficulties reported in strenuous physical activities and long walks may be associated with symptoms like asthenia induced by chemotherapy or with psychological aspects, as difficulty sleeping (66%) and tiredness (57%), also common in these patients. Another study reported a prevalence of severe global fatigue after treatment of 35.6%, and that it endures for years [40]. This should be addressed in the follow-up of BC survivors, as it has a potentially significant detrimental impact on patients’ QoL. Psychological monitoring, downgraded for far too long, may have a key role in this context [21,41].

Pain was the most frequent symptom reported by BC survivors (57%) and interfered with daily activities in 46%. This figure is similar to what had been reported in another study (51%) [11]. Several explanations can be put forward to justify such a high prevalence of this symptom: it may be undervalued by doctors; patients may fail to mention it in consultation due to the reduced time of medical appointments; patients may think that pain is a normal symptom given their clinic situation; and/or patients may focus their attention on disease prognosis and neglect QoL.

Approximately one-quarter of patients in this study considered that social and family activities were impaired due to the disease and its treatments (23% and 26%, respectively), which may be related to the high percentage (71%) that reported psychological effects, including increased levels of depression and irritability. More than half of patients (56%) referred that BC and its treatments had an impact on work and daily activities. This raises awareness of the need for developing and implementing alternative working options for BC survivors, such as part-time and/or remote working or adjusting schedules in a way that allows these patients to maintain their work activity while undergoing or recovering from the disease and its treatments. According to data in the literature, two years after BC diagnosis, 21% of patients had not returned to work yet [19]. This evidence reinforces the need for alternative working options or even changes in professional field that can accommodate the new limitations imposed by the disease. Although hospital care and anticancer oral medications are free of charge in the Portuguese public service, and the proportion of reimbursement due to medical leave is high, 34% of patients in this study reported financial difficulties. This percentage might be explained by the high proportion of people in temporary or precarious working situations in Portugal, with consequently low social security protection. The precarious socioeconomic status of these patients is also suggested by the low monthly household income (≤1200€) reported by 34% of study participants. Most patients reported not feeling physically less attractive (68%), having no difficulties looking at their naked body (69%), and not feeling less feminine (70%) due to BC. This may in part be due to the comprehensive range of solutions that are currently available for BC survivors, such as wigs and scarves, and eventually also to the fact that BC surgery is increasingly moving from mutilating procedures to breast-conserving and reconstructive ones. Breast reconstruction is now a free option in public hospitals, although not always possible at the same time of mastectomy, as others have also reported [42]. Younger women (<60 years) in this study reported worse social functioning. Although speculative, this may be explained by their previously more active life compared to older women, making them notice a greater impact of the disease, or by having been submitted to more aggressive treatments. Concerns with body image and hair loss were also aggravated in younger women. A total of 71% were sexually inactive, which is a very high percentage compared to the 23.9% reported elsewhere [43]. However, when assessing sexual functioning according to age, it was better in the age group below 60 years, in agreement with another study [8]. It would have been interesting to compare the periods before and after treatment to draw further conclusions, as it is acknowledged that undergoing chemotherapy or endocrine therapy has a great impact in sexual functioning [11], and even potentially impact treatment adherence. As expected, low socioeconomic status was associated with aggravated financial difficulties, but a curious finding was that it also had worse score in the physical functioning scale. This study showed that the stage of BC affects patients’ QoL, with women with advanced disease experiencing worse global health status, worse physical, role, and cognitive functioning, and more pain and side effects from systemic therapy than women with localized/locally advanced disease. Although the association of more advanced disease stages with poorer QoL was to be expected, others have reported that women with early BC attain higher levels of emotional distress, experiencing anxiety, depression, and irritability, with an impact on QoL compared to women with advanced BC [44–46]. This indicates that, regardless of the stage of disease, it always carries a non-negligible burden in patients’ QoL. The body of evidence retrieved from this study and from previous ones suggests that the routine assessment of BC patients’ QoL should be incorporated into the clinical practice through the application of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs), ideally before, during and after BC treatment.

Study limitations

This study had some limitations that should be acknowledged. Participants' level of literacy may represent a study limitation, as the questionnaires applied required some level of understanding and literacy from respondents, which was not ensured. On the other hand, due to its cross-sectional nature, the study did not take into account the fact that patients were in different stages of treatment, with some possibly even having finished treatment already. According to the literature, QoL in some patient clusters increases throughout treatment and follow-up, suggesting that patients adapt fairly well to the disease and its treatments [47, 48]. However, the cross-sectional design of this study did not allow to explore this issue. Finally, the limited number of patients included in the study due to initial bureaucratic issues and delays in the response of Ethic and Data Protection Commissions, which precluded the inclusion of more hospitals in the study, and to logistic difficulties in contacting patients by telephone or email, represents another study limitation that may weaken its external validity. Despite these limitations, this study provides novel and valuable insights into the QoL of BC patients and survivors in Portugal and should be used as a starting point for the development and implementation of measures accordingly.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that more attention should be paid to the unmet needs of BC survivors. The EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 scales can be valuable instruments to adopt in the patient’s journey to assess their QoL and thereby increase health professionals’ awareness of the points to improve to optimize their long-term outcomes.

Hopefully, this study will be a starting point for improving the personalized survivorship care of BC patients in Portugal. This includes but is not limited to referring patients to appropriate follow-up interventions, including physical, psychosocial, and lifestyle support, in addition to purely clinical. Patients’ referral to medical social workers and appropriate support services may also provide them with the necessary resources to reduce the financial burden of healthcare. The authors believe that this study makes a relevant contribution to improving BC care in Portugal and will substantiate and strengthen the application of preexisting specific guidelines that are still not routinely used in the clinical practice.

Declarations

Ethics Approval And Consent To Participate

This study was approved by the Administration Boards of participating hospitals, following approval by the respective Ethics Committees. It was also approved by the Portuguese National Data Protection Commission (CNPD).

Study design and conception were of the strict responsibility of study investigators.

All patients signed written informed consent prior to study enrolment.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all patients and healthcare providers who generously consent to participate in this study. They also acknowledge Pitagórica s.a. for helping conduct the study procedures.

Statements and Declarations

Funding

H360 project received an unrestricted grant from Pfizer.

Conflicts Of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Patrícia Miguel Semedo, Sara Coelho, Inês Brandão Rêgo, Laetitia Teixeira, Susana Sousa, and Francisco Pavão. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Patrícia Miguel Semedo, Sara Coelho, and Inês Brandão Rêgo and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The dataset generated and analyzed in the current study is not publicly available due to European Union general data protection regulations. They can be provided by the corresponding author, upon reasonable request, after approval by the local Government responsible for assessing the impact on data protection and by the study’s Institutional Ethics Committees.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Administration Boards of participating hospitals following approval by the respective Ethics Committees. The study’s design and conception were of the strict responsibility of study investigators. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate

All patients provided written informed consent prior to any study-specific procedure.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71 (2021): 209-249.

- Shapiro CL. Cancer Survivorship. Longo DL, editor. N Engl J Med 379 (2018): 2438-2450.

- World Health Organization. Portugal - Global Cancer Observatory. Globocan 2020. 501 (2020): 1-2.

- Cardoso F, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, et al. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 30 (2019): 1194-1220.

- American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer What is breast cancer?? Am Cancer Soc Cancer Facts Fig Atlanta, Ga Am Cancer Soc (2022): 1-19.

- Nardin S, Mora E, Varughese FM, et al. Breast Cancer Survivorship, Quality of Life, and Late Toxicities. Front Oncol 10 (2020): 1–6.

- Paluch-Shimon S, Cardoso F, Partridge AH, et al. ESO–ESMO 4th International Consensus Guidelines for Breast Cancer in Young Women (BCY4). Ann Oncol 31 (2020): 674-696.

- Institute of Medicine and National Research. Council of the National Academies. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (2006).

- Nekhlyudov L, Mollica MA, Jacobsen PB, et al. Developing a Quality of Cancer Survivorship Care Framework: Implications for Clinical Care, Research, and Policy. Vol. 111, Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Oxford University Press (2019): 1120-1130.

- Biddell CB, Spees LP, Mayer DK, et al. Developing personalized survivorship care pathways in the United States: Existing resources and remaining challenges. Cancer. John Wiley and Sons Inc 127 (2021): 997-1004.

- Ferreira AR, Di Meglio A, Pistilli B, et al. Differential impact of endocrine therapy and chemotherapy on quality of life of breast cancer survivors: a prospective patient-reported outcomes analysis. Ann Oncol 30 (2019): 1784-1795.

- Linden W, Vodermaier A, MacKenzie R, et al. depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord 141 (2012): 343-351.

- Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, et al. Quality of life at the end of primary treatment of breast cancer: First results from the moving beyond cancer randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 96 (2004): 376-387.

- Partridge AH, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, et al. Effects of Chemotherapy and Combined Chemohormonal Therapy in Women With Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr ( 2001): 135-142.

- Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, et al.Physical and psychosocial recovery in the year after primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29 (2011): 1101-1109.

- Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, et al. Quality of Life in Long-Term, Disease-Free Survivors of Breast Cancer: a Follow-up Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 94 (2002): 39-49.

- Partridge AH, Winer EP. Long-Term Complications of Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Early Stage Breast Cancer. Breast Dis 21 (2004): 55-64.

- Vaz-Luis I, Cottu P, Mesleard C, et al. UNICANCER: French prospective cohort study of treatment-related chronic toxicity in women with localised breast cancer (CANTO). ESMO Open 4 (2019): e000562.

- Dumas A, Luis IV, Bovagnet T, et al. Impact of Breast Cancer Treatment on Employment: Results of a Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study (CANTO). J Clin Oncol 38 (2020): 734-743.

- Di Meglio A, Soldato D, Presti D, et al. Lifestyle and quality of life in patients with early-stage breast cancer receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy. Curr Opin Oncol 33 (2021): 553-573.

- Brauer ER, Long EF, Petersen L, et al.Current practice patterns and gaps in guideline-concordant breast cancer survivorship care. J Cancer Surviv (2021).

- Cardoso F, Paluch-Shimon S, Senkus E, et al. 5th ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 5). Ann Oncol 31 (2020) :1623-1649.

- Cherny NI, Dafni U, Bogaerts J, et al. ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale version 1.1. Ann Oncol 28 (2017): 2340-2366.

- Coelho S, Rego IB, Dionísio MR, et al. 360 Health Analysis (H360) – A Proposal for an Integrated Vision of Breast Cancer in Portugal. Eur J Breast Heal 16 (2020): 91-98.

- Sara A, Universidade S, Portuguesa C. 360 Health Analysis - Breast Cancer Management in Portugal?: Patient Journey 21 (2021): 230-244.

- Phillips R, Gandhi M, Cheung YB, et al. Summary scores captured changes in subjects’ QoL as measured by the multiple scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30. J Clin Epidemiol 68 (2015): 895-902.

- Pais-Ribeiro J, Pinto C, Santos C. Validation study of the portuguese version of the QLC-C30-V.3. Sociedade Portuguesa de Psicologia da Saúde. ISSN # 1645-0086. PSAU - Artigos em revistas nacionais (2008).

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85 (1993): 365-376.

- Virliani C, Kurniawan A, Putri H. Validation of QLQ-BR23 Questionnaire in Measurement of Quality of Life of Breast Cancer Patients: A Pilot Study. Ann Oncol (2019).

- Fayers PM, Bottomley A. EORTC Quality of Life Group; Quality of Life Unit. Quality of life research within the EORTC-the EORTC QLQ-C30. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Eur J Cancer (2002): 125-133.

- Karsten MM, Roehle R, Albers S, et al. Real-world reference scores for EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-BR23 in early breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 163 (2022): 128-139.

- Sprangers MA, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: first results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol (1996).

- de Ligt KM, de Rooij BH, Walraven I, et al. 134P_PR Towards tailored follow-up care for breast cancer survivors: Cluster analyses based on symptom burden. Ann Oncol 32 (2021): S80.

- Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for determination of sample size and interpretation of the European organisation for the research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire core 30. J Clin Oncol 29 (2011) :89-96.

- Luckett T, King MT, Butow PN, et al. Choosing between the EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G for measuring health-related quality of life in cancer clinical research: Issues, evidence and recommendations. Vol. 22, Annals of Oncology. Oxford University Press (2011): 2179-2190.

- Alessandra F, Michels S, Maria I, et al. Validity, reliability and understanding of the EORTC-C30 and EORTC-BR23, quality of life questionnaires specific for breast cancer Validação, reprodutibilidade e compreensão do EORTC-C30 e EORTC-BR23, questionários de qualidade de vida específicos para câncer de mama. Rev Bras Epidemiol 16 (2013).

- Costa WA, Eleutério J, Giraldo PC, et al. Quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Rev Assoc Med Bras 63 (2017): 583-589.

- Chopra I, Kamal KM. A systematic review of quality of life instruments in long-term breast cancer survivors. Health Qual Life Outcomes (2012).

- Penttinen H, Rautalin M, Roine R, et al. Quality of Life of Recently Treated Patients with Breast Cancer. Anticancer Res 34 (2014): 1201-1206.

- Meglio A Di, Havas J, Soldato D, et al. Development and Validation of a Predictive Model of Severe Fatigue After Breast Cancer Diagnosis: Toward a Personalized Framework in Survivorship Care. J Clin Oncol 40 (2022): 1111-1123.

- Nunes MDR, Nascimento LC, Fernandes AM, et al. Pain, sleep patterns and health-related quality of life in paediatric patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 28 (2019).

- Tsai HY, Kuo RNC, Chung KP. Quality of life of breast cancer survivors following breast-conserving therapy versus mastectomy: A multicenter study in Taiwan. Jpn J Clin Oncol 47 (2017): 909-918.

- da Costa FA, Ribeiro MC, Braga S, et al. Disfunção sexual em sobreviventes de cancro da mama: Adaptação cultural do sexual activity questionnaire para uso em Portugal. Acta Med Port 29 (2016): 533-541.

- Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Love A, et al. Psychiatric disorder in women with early stage and advanced breast cancer: a comparative analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 38 (2004): 320-326.

- Spiegel D. Cancer and depression. Br J Psychiatry Suppl (1996): 109–16.

- Tan ML, Idris DB, Teo LW, et al. Validation of EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23 questionnaires in the measurement of quality of life of breast cancer patients in Singapore. Asia-Pacific J Oncol Nurs (2014): 22-32.

- Arraras JI, Manterola A, Asin G, et al. Quality of life in elderly patients with localized breast cancer treated with radiotherapy. A prospective study. Breast (2016): 46-53.

- Di Meglio A, Havas J, Gbenou AS, et al. Dynamics of Long-Term Patient-Reported Quality of Life and Health Behaviors After Adjuvant Breast Cancer Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 40 (2022): 3190-3204.