Prevalence of Dentine Hypersensitivity among Adult Dental Patients in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania

Article Information

Lorna C Carneiro1*, Alex A Minja2

1Department of Restorative Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania

2Department of Restorative Dentistry, Arusha Lutheran Medical Center, Arusha, Tanzania

*Corresponding Authors: Lorna C Carneiro, Department of Restorative Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, P. O. Box 65451, Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania

Received: 28 May 2020; Accepted: 08 June 2020; Published: 11 June 2020

Citation: Lorna C Carneiro, Alex A Minja. Prevalence of Dentine Hypersensitivity among Adult Dental Patients in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania. Dental Research and Oral Health 3 (2020): 074-082.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Objective: To assess the prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity (DH) among adult patient’s attending public dental clinics in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania.

Material and methods: This hospital based cross-sectional study assessed adults aged 18 years and above who attended public dental clinics in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania. Prevalence of DH was clinically assessed in relation to age, sex, tooth type, presence of tooth wear (TW) and gingival recession (GR). Analysis of data used the SPSS program with level of statistical significance set at p<0.05.

Result: The 323 participant’s age ranged between 18 and 72 years. Majority of participants were in age group 18 to 30 years (33.7%) and females (52.9%). The prevalence of clinically diagnosed DH was 46.4% (n=150) which had a similar prevalence to tooth wear (46.4%) and gingival recession (45.5%). DH statistically significantly increased with age, presence of tooth wear and presence of gingival recession (p<0.05). Teeth most diagnosed with DH were the first molars in the lower jaw (63.5%). Participants without tooth wear (OR=0.137; 95% CI 0.07 - 0.24) or gingival recession (OR=0.161; 95% CI 0.09 - 0.28) are less likely to have clinically diagnosed DH.

Conclusion: This study demonstrates that prevalence of clinically diagnosed DH among subjects was common (46.4%) with first molars in lower jaw being most affected (63.5%). DH had a statistically significant increase with age, tooth wear and gingival recession however, logistic regression indicated that those without tooth wear or gingival recession were less likely to have DH.

Keywords

Dentine Hypersensitivity, Tooth Wear, Gingival Recession, Adults, Dental Patients, Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania

Dentine Hypersensitivity articles, Tooth Wear articles, Gingival Recession articles, Adults articles, Dental Patients V articles, Dar-es-salaam articles, Tanzania articles

Dentine Hypersensitivity articles Dentine Hypersensitivity Research articles Dentine Hypersensitivity review articles Dentine Hypersensitivity PubMed articles Dentine Hypersensitivity PubMed Central articles Dentine Hypersensitivity 2023 articles Dentine Hypersensitivity 2024 articles Dentine Hypersensitivity Scopus articles Dentine Hypersensitivity impact factor journals Dentine Hypersensitivity Scopus journals Dentine Hypersensitivity PubMed journals Dentine Hypersensitivity medical journals Dentine Hypersensitivity free journals Dentine Hypersensitivity best journals Dentine Hypersensitivity top journals Dentine Hypersensitivity free medical journals Dentine Hypersensitivity famous journals Dentine Hypersensitivity Google Scholar indexed journals Tooth Wear articles Tooth Wear Research articles Tooth Wear review articles Tooth Wear PubMed articles Tooth Wear PubMed Central articles Tooth Wear 2023 articles Tooth Wear 2024 articles Tooth Wear Scopus articles Tooth Wear impact factor journals Tooth Wear Scopus journals Tooth Wear PubMed journals Tooth Wear medical journals Tooth Wear free journals Tooth Wear best journals Tooth Wear top journals Tooth Wear free medical journals Tooth Wear famous journals Tooth Wear Google Scholar indexed journals Gingival Recession articles Gingival Recession Research articles Gingival Recession review articles Gingival Recession PubMed articles Gingival Recession PubMed Central articles Gingival Recession 2023 articles Gingival Recession 2024 articles Gingival Recession Scopus articles Gingival Recession impact factor journals Gingival Recession Scopus journals Gingival Recession PubMed journals Gingival Recession medical journals Gingival Recession free journals Gingival Recession best journals Gingival Recession top journals Gingival Recession free medical journals Gingival Recession famous journals Gingival Recession Google Scholar indexed journals Dental Patients articles Dental Patients Research articles Dental Patients review articles Dental Patients PubMed articles Dental Patients PubMed Central articles Dental Patients 2023 articles Dental Patients 2024 articles Dental Patients Scopus articles Dental Patients impact factor journals Dental Patients Scopus journals Dental Patients PubMed journals Dental Patients medical journals Dental Patients free journals Dental Patients best journals Dental Patients top journals Dental Patients free medical journals Dental Patients famous journals Dental Patients Google Scholar indexed journals Adults articles Adults Research articles Adults review articles Adults PubMed articles Adults PubMed Central articles Adults 2023 articles Adults 2024 articles Adults Scopus articles Adults impact factor journals Adults Scopus journals Adults PubMed journals Adults medical journals Adults free journals Adults best journals Adults top journals Adults free medical journals Adults famous journals Adults Google Scholar indexed journals Dar-es-salaam articles Dar-es-salaam Research articles Dar-es-salaam review articles Dar-es-salaam PubMed articles Dar-es-salaam PubMed Central articles Dar-es-salaam 2023 articles Dar-es-salaam 2024 articles Dar-es-salaam Scopus articles Dar-es-salaam impact factor journals Dar-es-salaam Scopus journals Dar-es-salaam PubMed journals Dar-es-salaam medical journals Dar-es-salaam free journals Dar-es-salaam best journals Dar-es-salaam top journals Dar-es-salaam free medical journals Dar-es-salaam famous journals Dar-es-salaam Google Scholar indexed journals dentistry articles dentistry Research articles dentistry review articles dentistry PubMed articles dentistry PubMed Central articles dentistry 2023 articles dentistry 2024 articles dentistry Scopus articles dentistry impact factor journals dentistry Scopus journals dentistry PubMed journals dentistry medical journals dentistry free journals dentistry best journals dentistry top journals dentistry free medical journals dentistry famous journals dentistry Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

Abbreviations:

DH-Dentine Hypersensitivity; TW-Tooth Wear; GR-Gingival Recession

1. Introduction

Dentin hypersensitivity (DH) [1] also known as dentine sensitivity [2] or cervical sensitivity/hypersensitivity [3] is characterized by “pain derived from exposed dentin in response to chemical, thermal tactile or osmotic stimuli which cannot be explained as arising from any other dental defect or disease”[4]. It has been demonstrated as a common problem in clinical dentistry [5, 6] and is likely to become more frequent in the future because of expected increases in longevity of the natural dentition [7]. Worldwide prevalence of DH reported was 1.34% in Nigeria [8] 11% in Kenya [9], 52.6%. in Saudi Arabia [10] and 67.7% in Hong Kong [11]. An even higher prevalence of 72-98% was reported among patients attending specialist periodontology departments [12, 13]. DH can affect

patients of any age and while some studies report that most affected patients are in the age group of 20-50 years, with a peak between 30 and 40 years of age [14] other studies report a first peak in 20 to 30 year olds and then another peak later in the 50s [15, 16]. Although the general consensus is that DH tends to be commoner among females [14] few studies [8, 17] report a higher prevalence among males and some studies report no gender difference [18]. Furthermore, DH has been linked with tooth wear [9, 19] and gingival recession [20, 21] and common tooth type reportedly affected by DH are premolars and canines [15, 16] with molars being least affected [6, 22]. Considering that DH is a diagnosis of exclusion [23] and the effected person is required to report the pain, omission of any reference to that person encourages the mistaken belief that the diagnosis of DH is objective [7]. Most of the reported studies on DH have been carried out using a patient questionnaire with no subsequent clinical examination [24]. However, clinical investigations of dentin hypersensitivity is claimed to be subjective as it depends on the individual reaction of the examined patients to different stimuli [25]. Information on the prevalence of clinically assessed DH is necessary for comparative studies worldwide and for recommending and planning of appropriate diagnosis and treatment modalities within the country.

2. Objective

This study aimed to provide baseline data on the clinically diagnosed prevalence of DH among adult patients attending the public dental clinics in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania in relation to age, sex, tooth type, presence of tooth wear (TW) and gingival recession (GR).

3. Materials and Methods

This hospital based cross sectional study was conducted in Dar-es-salaam, one of the highly populated cities of Tanzania with a population of 3.207 million people from all over the country [26]. One public hospital in each district (Kinondoni, Temeke and Ilala) and the only consultant referral hospital in the region were purposively selected based on the number of attending patients. The estimated sample size of 384 was calculated using a 50% proportion (p) of dentine hypersensitivity with a 95% confidence interval of 1.96 and margin of error of 5% (0.05). Based on the attending patient population at each hospital, proportion of participants at each selected hospital was determined.

At each facility, the study was introduced to patients awaiting dental treatment on a daily basis and a total of 345 participants aged 18 years and above who consented and fulfilled the inclusion criteria were recruited into the study. Those excluded from the study were the very ill, mentally challenged, on anti-inflammatory or analgesics prescriptions or desensitizing therapy, with dental caries or tooth/root fracture, having filled or root canal treated tooth/teeth, or with fixed or removable prosthesis or orthodontic appliances. The clinical assessment of DH was conducted by seating subjects in a dental chair having an overhead light. Prior to determining presence or absence of DH using the tactile stimulus response [27] all tooth surfaces were gentle dried with cotton gauze by one of the authors who was calibrated (AAM). The tactile stimulus test using a World Health Organization probe was performed on all permanent teeth except third molars by using an initial low scrubbing force (equivalent to 5 gram force) followed by gradual escalation to the threshold level (not exceeding 20 gram force). Respondents were instructed to describe the extent of the pain/discomfort experienced while probing by using a five numerical verbal rating scale (VRS) from 0 to 4. Zero signified no discomfort/pain while mild discomfort/pain =1, moderate discomforts/pain= 2, severe pain only during application of stimulus= 3 and severe pain persisting after removal of stimulus=4. Patient’s responses for each tooth were recorded in the clinical record form and those who scored zero (0) for all teeth were considered as not having DH while those who scored 1 to 4 for any tooth were considered to have DH. TW was scored (0=no tooth wear; 1= tooth wear) when either attrition, abrasion, abfraction or erosion were observed [28] while GR was diagnosed when there was apical migration of the gingival attachment with any amount of root exposure (0=no gingival recession; 1= gingival recession). Age was grouped into 18-33 years =0 and 34-72 years =1 while sex was grouped as males =0 and females = 1. Validity of clinical assessment of DH, TW and GR was done at the Muhimbili University dental clinic and intra examiners consistency was assessed by requesting 10% of randomly selected subjects to repeat the clinical examination. Measures of agreement of the various scores ranged from Kappa 0.705 to 0.934. Analysis of data was performed using SPSS version 20. Frequency distribution and bivariate analysis was done and results with p-value of less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariate analysis was performed to take care of the confounding factors of DH. Ethical clearance to conduct this study was granted by Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (Ref.No.MU/PGS/SAEC/Vol.VI/) while permission to conduct the research in respective dental clinics was obtained from the administrative authorities. Signed consent forms by participants ensured understanding of the study and right to participate.

4. Results

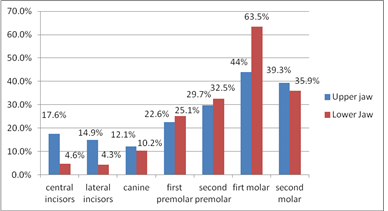

Of the sampled participants, 323 participated in the study giving a response rate of 93.6%. Participant’s age ranged between 18 and 72 years. Majority of participants were in age group 18 to 30 years (33.7%) and females (52.9%). The prevalence of clinically diagnosed DH of 46.4% was similar to that of TW (45.5%) and GR (46.4%) as shown in Table 1. Shown in Table 2 is the distribution of clinically diagnosed DH among study participants by assessed variables. The prevalence of clinically diagnosed DH was statistically significantly lower in age group 18-30 years (38.9%) than age group 31-72 years (51.6%). Many more males were clinically diagnosed to have DH compared to females however this difference was not statistically significant. Participants clinically diagnosed with DH had statistically significantly more TW (72%) and GR (70.7%) in comparison to their counterparts (p≤0.001). Percent distribution of subjects with clinically diagnosed DH by tooth type and jaw is shown in Figure 1. Subjects teeth most diagnosed with DH were the first molars in the lower jaw (63.5%) followed by upper jaw (44%), second molars in the upper (39.3%) and lower jaw (35.9%), second premolars in the lower jaw (32.5%) and upper jaw (29.7%), first premolar in the lower jaw (25.1%) and upper jaw (22.6%) respectively. A lower prevalence of DH was observed in upper central incisors (17.6%), lateral incisors (14.9%) and canines (12.1%) compared to an even lower prevalence in canines (10.2%) and central (4.6%) and lateral (4.3%) incisors of the lower jaw. Variables with statistically significant relationship with clinically diagnosed DH during bivariate analysis were analysed by multivariate analysis to take care of the confounding factors. Participants without tooth wear are less likely (OR=0.137; 95% CI 0.07 - 0.24) to have clinically diagnosed DH and those who do not have gingival recession are less likely (OR=0.161; 95% CI 0.09 - 0.28) to have clinically diagnosed DH (Table 3).

|

Age groups |

n |

( % ) |

|

18 to 30 yrs |

131 |

40.6 |

|

31 to 72 yrs |

192 |

59.4 |

|

Sex |

||

|

Male |

152 |

47.1 |

|

Female |

171 |

52.9 |

|

Clinically diagnosed DH |

||

|

Absent |

173 |

53.6 |

|

Present |

150 |

46.4 |

|

Tooth wear |

||

|

Absent |

176 |

54.5 |

|

Present |

147 |

45.5 |

|

Gingival recession |

||

|

Absent |

173 |

53.6 |

|

Present |

150 |

46.4 |

Table 1: Distribution of study participants by assessed variables.

|

Age groups |

Clinically diagnosed DH |

Chi square; p-value |

||

|

Absent |

Present |

Total |

||

|

n (%) |

n (%) |

n (%) |

||

|

18 to 30 yrs |

80 (61.1) |

51 (38.9) |

131 (100) |

χ2=4.995 p=0.025 |

|

31 to 72 yrs |

93 (48.4) |

99 (51.6) |

192 (100) |

|

|

Sex |

||||

|

Male |

73 (48.0) |

79 (52.0) |

152 (100) |

χ2=3.535 p=0.06 |

|

Female |

100 (58.5) |

71 (41.5) |

171 (100) |

|

|

Tooth wear |

||||

|

Absent |

132 (75.0) |

44 (25.0) |

176 (100) |

χ2=71.466 p≤0.001 |

|

Present |

41 (27.9) |

106 (72.1) |

147 (100) |

|

|

Gingival recession |

||||

|

Absent |

129 (74.6) |

44 (25.4) |

173 (100) |

χ2=66.087 p≤0.001 |

|

Present |

44 (29.3) |

106 (70.7) |

150 (100) |

|

Table 2: Distribution of clinically diagnosed DH among study participants by assessed variables.

Figure 1: Percent distribution of subjects with clinically diagnosed DH by tooth type and jaw.

|

Predictors |

Sig. |

Odds Ratio (OR) |

95% C.I. |

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

|||

|

Age group |

0.455 |

1.247 |

0.69 |

2.22 |

|

Tooth wear |

0.000 |

0.137 |

0.07 |

0.24 |

|

Gingival Recession |

0.000 |

0.161 |

0.09 |

0.28 |

Table 3: Logistic regression Odds ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence interval (CI) of age group, tooth wear and gingival recession of subjects by clinically diagnosed dentine hypersensitivity.

5. Discussion

This hospital-based cross-sectional study aimed to provide base line data on the prevalence of DH among adult dental patients aged 18-72 years in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania in relation to age, sex, tooth type, presence of tooth wear (TW) and gingival recession (GR). Purposeful selection of hospitals was based on accessibility of the residents from different localities and served as a representation of participants from all over the country. Obtained baseline data on the magnitude of DH cannot be generalized as it involves patients presenting to dental clinics within the country and provides basis for comparative studies worldwide. Clinicians however are made aware of the prevalence of DH and its relationship to age, sex, tooth type, presence of tooth wear (TW) and gingival recession (GR). Clinically diagnosed prevalence of DH of 46.4% in this study was similar to the reported 42.4% in Saudi Arabia [10] and was within the prevalence range of 3% to 57% reported in other studies [29, 30]. Contrastingly, a higher prevalence of 68% was reported among patients attending a dental hospital in Hong Kong [11] and an even higher prevalence of 72-98% was reported among patients attending specialist periodontology departments [13, 12]. Differences in the reported findings could be related to patient selection and diagnostic methodology employed. In accordance with most studies [31-33], prevalence of clinically diagnosed DH was reported to be statistically significantly higher in the older age group of 31-72 years. In disagreement, some studies report a first peak of DH in 20 to 30 year [15, 16] while another study reported that DH can affect patients of any age [14]. The difference in reported findings could be related to the categorization of age groups, and further studies are needed to determine the possible cumulative effect of DH with age. The general consensus is that DH tends to be commoner among females [34] however, Bamise et al. [8] reported a male predominance in clinically diagnosed DH. Similar to findings from this study, other studies [18, 35] also found no statistical significant difference in the prevalence of DH among males or females. The possible reason for the lack of gender difference in this study could be related to similarities by both males and females in dietary and oral hygiene practices. Participants clinically diagnosed with DH in this study had statistically significantly more TW and GR in comparison to their counterparts. Similar significant associations were reported by West et al. [18]. Inadequate level of knowledge and practices on oral health that cause enamel or cementum loss and gingival recession could explain the reported differences. Most studies agree that DH is common in premolars and canines [29, 36] and that molars are least affected [6, 22]. Contrastingly this study found that molars were more affected by DH. While in Hong Kong lower incisors were the most commonly affected teeth [11] this study found lower incisors least affected by DH. Prevalence of affected teeth by DH in this study can be explained by the consumption of abrasive foods unlike in developed countries where most types of foods are processed. Studies have demonstrated that acidic foods and drinks can soften enamel leading to significant tooth wear, particularly when combined with mechanical cleaning [3] and in line with other studies [37] findings from this study report that persons without tooth wear are less likely to have DH. In addition, similar to findings of this study, another study [38] reported that participants without gingival recession are less likely to have DH.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that prevalence of clinically diagnosed dentine hypersensitivity among subjects was common with first molars in lower jaw being most affected. DH had a statistically significant increase with age, tooth wear and gingival recession however, logistic regression indicated that those without tooth wear or gingival recession were less likely to have DH.

Acknowledgments

Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, authorities of the dental facilities and participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Supplementary Materials

No supplementary material has been provided.

References

- Bubteina N, Garoushi S. “Dentine Hypersensitivity: A Review,”. Dentistry 5 (2015): 5-9.

- Miglani S, Aggarwal V, Ahuja B. “Dentin hypersensitivity: Recent trends in management,”. J Conserv Dent 13 (2010): 218-224.

- Addy M. “Dentine hypersensitivity: New perspectives on an old problem.,”. Int Dent J 52 (2002): 367-375.

- Canadian Advisory Board on Dentin Hypersensitivity, “Consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity.,” J. Can. Dent. Assoc 69 (2003): 221-226.

- Rösing C, Fiorini T, Liberman D, et al. “Dentine hypersensitivity: Analysis of self-care products,”. Braz. Oral Res 23 (2009): 56-63.

- Azodo C, Amayo A. “Dentinal sensitivity among a selected group of young adults in Nigeria.,”. Niger Med J 52 (2011): 189-192.

- Robinson P. Dentine Hypersensitivity: Developing a Person-Centred Approach to Oral Health. 1st ed. Academic Press, Elsevier, 32 Jamestown Road, London NW1 7BY, UK (2015).

- Bamise C, Olusile A, Oginni A, et al. “The prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity among adult patients attending a Nigerian teaching hospital,”. Oral Heal. Prev. Dent 5 (2007): 49-53.

- Hamid L. “Prevalence and the factors associated with dentine hypersensitivity among patients visiting the university dental hospital,” (2009).

- Taani D, Awartani F. “Prevalence and distribution of dentin hypersensitivity and plaque in a dental hospital population,”. Quintessence Int 32 (2001): 372-376.

- Rees J, Jin L, Lam S, et al. “The prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity in a hospital clinic population in Hong Kong,”. J Dent 31 (2003): 453-461.

- Chabanski M, Gillam D, Bulman J, et al. “Prevalence of cervical dentine sensitivity in a population of patients referred to a specialist Periodontology Department,”. J Clin Periodontol 23 (1996): 989-992.

- Chabansk M, Gillam D, Bulman J, et al. “Clinical evaluation of cervical dentine sensitivity in a population of patients referred to a specialist periodontology department: a pilot study,”. J Oral Rehabil 24 (1997): 666-672.

- Flynn J, Galloway R, Orchardson R. “The incidence of ‘hypersensitive’ teeth in the West of Scotland,”. J Dent 13 (1985): 230-236.

- Gillam D, Aris A, Bulman J, et al. “Dentine hypersensitivity in subjects recruited for clinical trials: clinical evaluation, prevalence and intra-oral distribution,”. J Oral Rehabil 29 (2002): 226-231.

- Splieth C, Tachou A. “Epidemiology of dentin hypersensitivity,”. Clin Oral Investig 17 (2013): 3-8.

- Rane P, Pujari S, Patel P, et al. “Epidemiological Study to Evaluate the Prevalence of Dentine Hypersensitivity among Patients,”. J Int Oral Heal 5 (2013): 15-19.

- West N, Sanz M, Lussi A, et al. “Prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity and study of associated factors: a European population-based cross-sectional study,”. J Dent 14 (2013): 841-851.

- Addy M. “Tooth brushing, tooth wear and dentine hypersensitivity--are they associated?,”. Int Dent J 55 (2005): 261-267.

- Drisko C. “Dentine hypersensitivity – dental hygiene and periodontal considerations,”. Int. Dent. J 52 (2002): 385-393.

- Drisko C. “Oral hygiene and periodontal considerations in preventing and managing dentine hypersensitivity,”. Int. Dent. J 57 (2007): 6.

- Martínez-Ricarte J, Faus-Matoses V, Faus-Llácer V, et al. “Dentinal sensitivity: Concept and methodology for its objective evaluation,”. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 13 (2008): 201-206.

- Jacobsen P, Bruce G. “Clinical Dentin Hypersensitivity: Understanding the Causes and Prescribing a Treatment,”. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract 2 (2001): 1-8.

- Irwin C, McCusker P. “Prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity in a general dental population,”. J Ir Dent Asso 43 (1997): 7-9.

- Gillam D, Orchardson R, Närhi M, et al. Present and future methods for the evaluation of pain associated with dentine hypersensitivity. London: Martin Dunitz Ltd (2000).

- National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance Dar es Salaam. “The United Republic of Tanzania Population Distribution by Age and Sex UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA, ADMINISTRATIVE BOUNDARIES i,” (2013).

- Orchardson R, Collins W. “Thresholds of hypersensitive teeth to 2 forms of controlled stimulation,”. J Clin Periodontol 14 (1987): 68-73.

- Idon P, Esan T, Bamise C. “Etiological factors for dentine hypersensitivity in a Nigerian population,”. South African Dent. J 73 (2018): 362-366.

- Rees J. “The prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity in general dental practice in the UK.,”. J Clin Periodontol 11 (2000): 860-865.

- Rees J, Addy M. “A cross-sectional study of dentine hypersensitivity.,”. J Clin Periodontol 29 (2002): 997–1003.

- Dhaliwal J, Palwankar P, Khinda P, et al. “Prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity: A cross-sectional study in rural Punjabi Indians,”. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol 16 (2012): 426-429.

- Bahsi E, Dalli M, Uzgur R, et al. “An analysis of the aetiology, prevalence and clinical features of dentine hypersensitivity in a general dental population,”. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 16 (2012): 1107-1116.

- Chrysanthakopoulos N. “Prevalence of Dentine Hypersensitivity in a General Dental Practice in Greece. Dental Surgeon DDSc. Resident in Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery, 401 General Military. Hospital of Athens, Athens,”. J Clin Exp Dent 33 (2011): 445-451.

- Idon P, Mohammed A, Ofuonye I, et al. “Dentine Hypersensitivity: Review of a Common Oral Health Problem,”. J. Dent. Craniofacial Res 2 (2017): 1-7.

- Al-Sabbagh M, Brown A, Thomas M. “In-office treatment of dentinal hypersensitivity,”. Dent Clin North Am 53 (2009): 147-160.

- Amarasena N, Spencer J, Ou Y, et al “Dentine hypersensitivity in a private practice patient population in Australia.,” J Oral Rehabil 38 (2011): 52-60.

- Gillam D, Richard K Chesters, David C Attrill, et al. “Dentine hypersensitivity - guidelines for the management of a common oral health problem.,”. Dent Updat 40 (2013): 514-516, 518-520, 523-524.

- Drisko C. “Oral hygiene and periodontal considerations in preventing and managing dentine hypersensitivity,”. Int. Dent. J 57 (2007): 399-410.